The ABC series Lost is the sort of extraordinary hit that TV dreams are made of.

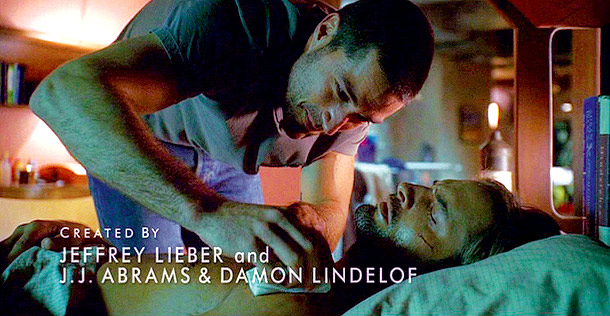

Centering on a band of plane-crash survivors marooned on a mysterious island, Lost has mixed sci-fi and plot twists into a huge phenomenon, attracting millions of viewers and propelling ABC out of a long prime-time ratings slump. When fans tune in to the show for the start of its fourth season in February 2008, one of the names they will see rolling in the opening credits as co-creator is Jeffrey Lieber. That's Jeffrey Lieber, Evanston Township High School, class of '87; U. of I., class of '91.

Lieber's success should lend itself to a heartwarming tale about a local kid who defied odds and made it big in show business. But the story is not that simple. In the Chutes & Ladders world that is Hollywood, Lieber finds his biggest triumph discomfiting. The network fired him after he wrote Lost's original series pilot. He doesn't know the crew or cast. He has never visited the writers' offices for the show and never set foot on the set in Hawaii, where much of the series is shot. Lieber won his credit only after a fight for recognition with ABC.

Nobody needs to feel sorry for Jeffrey Lieber: because of that successful arbitration, Lost has served him quite well financially. But he finds that a hollow victory. "It's money for therapy," he says, with a laugh.

Jeffrey Lieber's story provides a case study in the rigors, pitfalls, and payoffs of a business that remains deeply alluring. Every year, countless wannabe film and television writers from all over the world descend on Hollywood to try to break in. Besides the glamour, the payoff can be golden: top movie and TV writers typically receive annual paychecks in the high six figures; with back-end profits, they can sometimes earn millions.

Still, only about 4,000 writers actually earn a living at the trade, according to the Writers Guild of America. Jeffrey Stepakoff, a TV veteran whose recently published book Billion-Dollar Kiss offers a behind-the-scenes look at the business, says about two-thirds of those paid writers work in television, many on the staffs of shows. The business is tough enough, says Stepakoff, that about 20 percent of working writers cycle out of the industry every year. "It's a very small, insular community," he says.

Sitting on the upstairs back porch of his 1912 Craftsman bungalow in L.A.'s Venice Beach on a recent chilly night, Lieber, 38, with black hair, longish sideburns, and a goatee, recounts how he became Lost's unknown castaway. The tale begins in Evanston, where he grew up the son of Susan, a clinical psychologist, and Roland, an architect. He got his start in show business in high school. "I went to see a production of Scapino," he recalls. "There was this really hot blonde named Suzy Moore onstage, and I kept thinking, I want to do anything I can to get closer to her. So I just started doing plays." (As it happens, his future wife, Holly Long, was also in Scapino.)

After high school, Lieber enrolled in the theatre department at the University of Illinois and later came to Chicago to break into the city's theatre scene-meaning, he moved into a roach-infested two-flat in Bucktown, worked part-time at Starbucks, and took roles in shows at Victory Gardens, Shakespeare Repertory, and the National Jewish Theatre.

Tired of being a struggling actor, Lieber teamed up with another struggling actor from the U. of I., Michael Shapiro, to write scripts for TV sitcoms on spec (that is, without any promise of being paid). An actress friend in Los Angeles passed the scripts to her agent at Writers & Artists, a respected talent agency. Lieber says he recalls the man today only as "Jerry." Jerry liked their scripts and told them that he'd sign them on as clients. Soon, Lieber and Shapiro flew out to L.A. for a meeting. Lieber says that afterward, while lunching on Melrose Boulevard-in shorts, in January-he and Shapiro decided: "That's it: we're moving to California. Hallelujah!"

A month or two after arriving in Los Angeles, in March 1995, Lieber and Shapiro met with Jerry one morning to discuss a movie project. Later that day, Lieber called Jerry at his office with a question, only to find out that as of that afternoon, Jerry no longer worked at Writers & Artists. That meant Lieber and Shapiro were out, too. Lieber now suspects that they were never actually signed as clients: "We were probably what's known as ‘hip-pocketed,'" he explains, "where an agent says, ‘Oh, yeah, I'll work with you.' But he doesn't tell anyone else, and if you pan out on your own, great, then he'll sign you. If not, no one knows you exist. We didn't exist."

Eight months passed with no agent or job offers. Lieber toiled at a $10-an-hour day job for a company that developed video games and in his spare time he churned out screenplays. Shapiro, hobbled by writer's block, ultimately gave up on his Hollywood dreams and returned to Chicago, where today he is the new principal of Shepard Middle School in Deerfield. "I've always said that Jeff's like a shark-if he stops moving, he dies," says Shapiro. "So he's up at five o'clock in the morning, sitting in front of the laptop; then he falls asleep at about 8:30 [p.m.], and then he gets up in the middle of the night and he writes."

In the fine tradition of Hollywood networking, Lieber passed his scripts on to an old high-school friend whose girlfriend worked as an assistant to a talent agent who was friends with an assistant to a literary agent, who read them. The agent agreed to sign Lieber, but with a catch: she was in the process of switching agencies and would seal the deal when she settled in elsewhere. Two weeks later, she called Lieber from her new agency. "Have you ever heard of Writers & Artists?" she asked. Lieber recalls thinking, "Oh, God, how could this be happening?"

Still, he signed with her and finally got his break. The studio Dreamworks liked one of his pitches and he became a finalist to write a romantic movie comedy. Unfortunately, he was up against John Patrick Shanley, the Academy Award–winning writer of Moonstruck. "I think I'm toast," recalls Lieber. "So, I go out and I buy a fishbowl and a goldfish, and I send it to [the Dreamworks executive] with a card that says, ‘Just remember-the little fish take up less room and they're easier to care for; hire the little fish.'" Lo and behold, Lieber got the job.

About a week later, Lieber met with the executive in his office, and the fishbowl was empty on the desk: "I said, ‘What happened to the fish?' And he says, ‘The fish is dead-we overfed it.'" (Later, Lieber was fired from the project and the movie was never made.)

The idea for Lost was born in the summer of 2003 in the banquet room of the Grand Californian hotel at Disney's California Adventure, in Anaheim. ABC had gathered its executive team, some 50 or so people, for the yearly management retreat, with a goal to generate fresh ideas for new shows and suggest ways to improve its existing ones. At the time, ABC-which is owned by Disney-was desperate for hits. The network had slipped to fourth in the ratings, behind NBC, CBS, and Fox, and development executives were feeling the heat.

At one point, the group sat around the banquet room and one by one suggested ideas for shows. When his turn came, Lloyd Braun, then the chairman of ABC Entertainment, suggested coming up with something along the lines of his favorite movie of that year, Cast Away, the stranded-on-a-deserted-island tale starring Tom Hanks. "A lot of people sort of laughed at the idea," recalls Thom Sherman, a former senior vice president at ABC, now with the CW network. Some skeptics compared the idea to Gilligan's Island, the goofy sixties sitcom.

But Sherman liked the idea (after all, Braun was his boss), and he called his good friend Ted Gold, then at Spelling Productions, the hit-making production company founded by TV legend Aaron Spelling. As it happened, says Gold, Spelling had toyed with a similar idea-a scripted series inspired by the reality TV show Survivor-but found no takers. So, when Sherman called with Braun's idea for the series, it seemed like the perfect marriage. And Gold had the perfect writer for the project: Jeffrey Lieber.

By this time, Lieber was enjoying some success, at least by Hollywood standards. He'd sold his first screenplay, a postcollege love-triangle drama titled Conspiracy of Weeds, and he got hired to write scripts for Warner Brothers and Paramount. Of those projects, only Weeds ever made it to the big screen. Picked up by Miramax, renamed Tangled, rewritten as a thriller, and miscast with a teen-comedy actress as the lead, the film flopped when it came out in 2003. (Lieber recalls being in a Paris train station on vacation and seeing a poster for his film, now called Sex Trouble.) Next, Disney hired Lieber to put a new twist on a film version of Natalie Babbitt's children's classic Tuck Everlasting.

He'd been hired and fired from other projects-a practice that is almost as old as Hollywood itself-but he'd come to know a producer who ended up at Spelling, and she had introduced him to Ted Gold, the company's drama chief. Gold worked with Lieber on a pilot pitch that got no takers, followed by another project that UPN hired Lieber to write but never made. Gold liked Lieber, however, and the exec signed him to a so-called blind deal-an agreement for a future project that's not necessarily identified. Lost became that project.

Gold recalls that ABC wanted its survivor drama to be a hyperrealistic portrayal of life on a deserted island: "Thom [Sherman] said to me, ‘We want to do Cast Away-the Series.' That's the only line that was ever pitched."

Lieber imagined something like Lord of the Flies-a "realistic show about a society putting itself back together after a catastrophe." In roughly a week's time, he concocted a general story line centered on what happens to a few dozen plane-crash survivors when they are stuck on a far-off Pacific island. The show, as Lieber saw it, would focus heavily on eight to ten main characters-in particular, two half brothers, avowed rivals, competing for leadership of their fellow castaways, who include a doctor, a con man, a fugitive, a pregnant woman, a drug-addicted man, a military officer, and a spoiled rich girl. (Sound familiar, Lost fans?)

In September 2003, Lieber pitched his premise for the show, then titled Nowhere, to Sherman and his lieutenants. "I won't be so presumptuous as to say it was one of the best pitches ever," recalls Gold, who was there. "I will say it was one of the more well-thought-out pitches I've been in." Afterward, continues Gold, "Thom called me and he told me, quote-unquote, ‘The best project of the year.' He greenlights it enthusiastically."

Lieber then spent weeks writing an elaborate outline, fleshing out the characters and story lines. Spelling brought in National Geographic experts as consultants to help Lieber ground his fictional island in reality. Soon enough, Lieber made another presentation to Sherman and the ABC development team. Lieber recalls that they had only one major complaint: they told him to cut a scene in which a shark killed one of the castaways. Too unrealistic, Lieber recalls them saying.

Next came six weeks writing the pilot. Just after Thanksgiving, Lieber met with ABC executives for a session at which they made suggestions for changes. He recalls only minor quibbles-things like refining a couple of characters and tweaking some dialogue. "We're really happy," he says Sherman told him after the meeting. "If you don't hand in blank pages on the rewrite, we're shooting this thing." Lieber was ecstatic. "Nobody tells you they're shooting anything-ever. That's the best news you can get."

Indeed, the networks consider hundreds, perhaps thousands, of pitches for new show ideas every television season. Jeffrey Stepakoff says each network typically buys 100 or so projects (ABC bought 80 that season), out of which only about 15 actually get produced. And of those, only seven or so actually make it on the air, with maybe two or three of those surviving beyond the first year. "The odds are remarkable," says Stepakoff.

Still, Lieber felt he had a good shot; so did Gold. "I thought it was a done deal," Gold says. The last step was to get Lloyd Braun to sign off. Over the Christmas holidays, Braun took Lieber's script with him to the La Quinta resort near Palm Springs.

"It was not received well," Jonathan Levin, then the president of Spelling, told Lieber a few days after Christmas. So the writer went back to work, but he had little time to revise the script and little to go on. Lieber was "rewriting like hell," he says, but he "didn't know what to do. I wasn't being told really what the problem was-all I was being told was that Lloyd didn't like it." He handed in a new draft a week later, just after the new year, and then waited nervously.

A few days later, Sherman called. "He says, ‘Great job on the rewrite,'" Lieber recalls. "‘I really like it.'" Sherman told him that he had some more notes and would call again in an hour. Lieber was hugely relieved. But hours passed with no word from Sherman or anyone else at ABC. Finally, in the late afternoon, Levin called. "Are you sitting down?" he asked. "It's over; you're done."

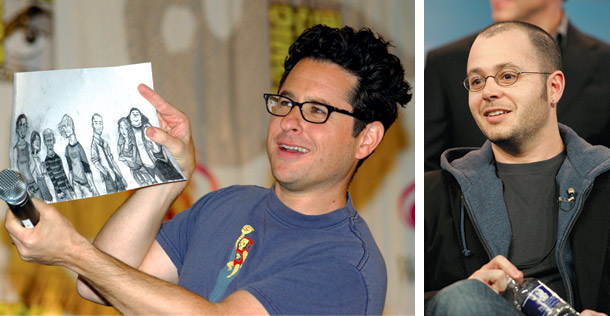

What happened next to Lost has become industry lore. Braun decided to give the project to a young hot shot named J. J. Abrams, who had helped create the ABC cult favorite Alias, among other things. But Abrams was tied up writing another pilot and he was skeptical that the show's premise could be extended to a whole season of episodes. Braun told him to take the weekend to think about it. Abrams did, and came back with a far-out idea to get around the show's limitations: What if the island were a character-a supernatural place where strange things happened? Braun loved it.

By this time, it was extremely late to be starting over from scratch. "But Lloyd was so passionate about it, he wanted to take an eleventh-hour stab at saving it," Sherman says. So Abrams teamed up with a promising writer named Damon Lindelof, and together they came up with another ingenious idea: a flashback device that focuses on one character each episode and allows the show to get off the island. Four days later, they submitted a 20-page outline to Braun. "Lloyd called me up screaming, ‘They've done it-it's ER, it's ER!'" recalls Sherman, referring to NBC's longtime hit series.

ABC picked up the pilot without a script, based solely on the outline by Abrams and Lindelof-an almost unheard-of move; less than three months later the pair were making a two-hour-long, $12-million pilot, one of the most expensive pilots in TV history. "I don't know if there's another story like this in the annals of television," says Sherman.

Lieber went into a funk for weeks. "I was angry and depressed and confused," he says. The hardest part was that he never saw it coming. "It's the flip between ‘We love it' to ‘There's a problem' that I've never really gotten over. Had somebody said, ‘Lloyd thinks it's too real-maybe we need a monster or an otherworldly element'-I would've said, ‘OK, no problem.' But I just never got the chance."

Sherman acknowledges that Lieber did "yeoman's work," but he says that ultimately ABC felt more comfortable putting the show in Abrams's hands. It was nothing personal, adds Sherman: "Business is business."

In May, ABC announced that it would put the show in its 2004 fall lineup. Lieber felt even more disheartened: "Not only do they boot me off the island; now I look back and they're throwing a party on the island, and I'm sitting there floating 100 feet in the water on a shitty raft that's going nowhere."

But before ABC could put Lost on the air, the network had to straighten out the credits mess. By tradition, the Writers Guild of America settles disputes over who gets screenplay and story credit for film and television productions. The guild's arbitration process amounts to high-powered fisticuffs, with fame and fortune-sometimes millions of dollars-potentially at stake. Each side makes its case with a detailed and laborious examination of all the written material that goes into the evolution of the final script. A committee of three anonymous guild members makes a final ruling.

ABC and Touchstone, another Disney unit that co-produces Lost, initially tried to head off a potentially nasty arbitration battle, claiming to the guild that Lieber (and Spelling) had no creative input on Lost-that his project was completely different from the show that was eventually made. "They just tried to write us, particularly Jeffrey, completely out of the picture, as if we had nothing to do with it," recalls Gold.

"Now I feel like I've been kicked off the island, I'm on a shitty raft 100 feet out, they're having a party, and they're throwing chum in the water at me," Lieber says.

The guild rejected Touchstone's argument, and the parties agreed to arbitration. Lieber readily acknowledges that he has nothing to do with the current show (which, he jokes, seems more like Lord of the Rings than Lord of the Flies). But, he adds, "I felt like, if credit was going to be handed out, somewhere in that pile, I deserved something." He spent the next two weeks comparing his draft with the final shooting script, poring over them line by line to find similar plot developments, character traits, relationships, and even dialogue.

"It was easy to point out the parallels," he says. "I didn't feel as if I'd been robbed, but [comparing the scripts] I was able to go, ‘A equals A, B equals B,'" and so on. He compiled a ten-page digest of similarities and sent the list to the guild for a ruling. Then he waited.

About a month later, Lieber says, a representative of the guild called and said, "Congratulations." The guild had sided with Lieber, ruling that the coveted ‘created by' credit should be shared three ways. Specifically, Lieber says, he received 60 percent of the ‘created by' credit, while Abrams and Lindelof split the remaining 40 percent. (Guild officials refused to discuss the specifics of Lieber's case, saying that all arbitration proceedings are confidential. Braun, Abrams, and Lindelof declined to be interviewed for this story, as did executives for ABC.)

"This was the first of a thousand times someone said ‘Congrats' regarding the show, where it felt hollow and embarrassing, because I wanted to say, ‘But I didn't do anything,'" Lieber says. "‘I mean, I did something-and what I did was important-but it wasn't the thing you're congratulating me for.'"

On September 22, 2004, Lieber spent a quiet night at home with his wife, Holly, watching the première of Lost. There was the terrifying plane crash, the chaotic aftermath on a remote tropical island, and the introduction of the cast-all similar to what Lieber had sketched out in his script. But soon, there were strange, loud noises, followed by a mysterious force snatching up an injured pilot. Later on, a polar bear attacked the survivors.

Lieber was shocked at how the series had veered away from hyperreality to Jurassic Park. "Monsters?" he thought. "Really?" He recalled how ABC executives had told him to cut the "unrealistic" scene of a shark attack. "Had I pitched the same ideas that were in the pilot that aired," he says today, "I would have been laughed out of the room."

His discomfort peaked the following September at the 2005 Emmy Award ceremonies in L.A.'s famed Shrine Auditorium. Lost had the most nominations for a drama series, with 12 bids, including one for Lieber in the drama writing category-a nomination for the pilot episode in part "created by" him. Dressed in a newly purchased tuxedo, Lieber sat next to Lindelof. Abrams, who was also up for a directing award, sat a few rows in front of them. Lieber felt like a red-carpetbagger. He felt, well, lost. "To be in the midst of them, and have them be like, Who the hell is this guy? What's he doing here?" recalls Lieber. "It was utterly painful; I couldn't wait for it to be over. It was like being at a party where you know your mom has called and gotten you invited."

But at the urging of his lawyer and his agent, Lieber had decided to attend. "To not go, to sit at home and isolate myself, would only reinforce for me that I hadn't done anything," he says. "I wasn't under the delusion that it was going to be all fun."

As things turned out, the awkward moment of sharing the stage with the show's other principals never materialized: though Lost won six Emmys, the writing award for drama ended up going to the new medical drama House.

Notwithstanding the guild's ruling, some former members of ABC's development team think Lieber has received an undeserved break. After all, given the success of the show, it's hard to fault the decisions made by the network. One former executive, who asked not to be identified because Hollywood is a small town, says, "The fact that Jeff arbitrated and got credit and takes money away from J. J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof, who literally work on this show till two in the morning every day-I just don't feel bad for Jeffrey. He's collecting a buttload of cash. He should be laughing all the way to the bank."

Lieber says he gets paid every time an episode airs and again when episodes are rerun, annually collecting in the "low six figures." Once the show is sold into syndication, he could potentially earn much more in royalties. He doesn't apologize for the payout. "I own part of the genesis. That's what the ‘created by' credit is about. Lots of things happened subsequently, but what I did is somehow buried deep within the DNA of the show."

Another former ABC executive who also requested anonymity is skeptical. "If you gave the script [idea] to ten writers in town," the executive says, "the characters would've been the same."

As it turns out, the success of Lost has left others besides Lieber in its wake. Most of the top executives at ABC were gone before the show aired. Meanwhile, Lieber's career hasn't stalled. He's written a pilot that got shot but never aired, and multiple screenplays. One, The Express, a biopic about Ernie Davis, the first black Heisman Trophy winner-who died young of leukemia-was shot in Chicago from April through June. Lieber is currently working on pilots for Lifetime and Showtime-both six-figure deals.

He is no longer the little fish that he called himself years ago to the Dreamworks executive, but he still feels as if he's swimming against the current in Hollywood's high seas, and he still feels he has something to prove. "That's the hardest part-my greatest moment of disappointment is my greatest moment of recognition. And finding peace in that is a daily, weekly, monthly type of thing."

Click on the links to read excerpts from Nowhere, the precursor to the pilot episode of Lost.

EXCERPT 1

Leiber: "In my draft of Lost, I was working off a Lord of the Flies model, wherein a small group of people, cut off from the real world, are forced to reinvent society. What version of law and order who they create? What kind of morality would win out? Would the people who rose to power be benevolent, or is power itself corrupting? At the center of the society I imagined two half brothers, connected by their father, but raised very differently. This is their introduction."

EXCERPT 2

Lieber: "The biggest challenge with the show was removing, for the most part, the idea that these people would be saved any time soon. One doesn't want to have to spend every episode dwelling on "rescuers" or plans of escape. This scene that follows was my attempt to get the viewer to buy into the survivors' permanent residency."