During my greener days, procuring cannabis often necessitated a drive to the fringes of Champaign-Urbana for an awkward business transaction with a sketchy hippie who made me listen to hours of Dead bootlegs in his incense-laden living room. If we were lucky, my fellow herbal enthusiasts and I would score an invite to the off-campus home of a legendary downstate dealer, a horticulture graduate student whose hydroponic weed was so potent the skunky scent lingered halfway up the block.

Judging by the business-casual attire of the budding ganjapreneurs who have joined me on a Saturday afternoon for the seminar “How to Get into the Illinois Marijuana Business,” the profile of the pot seller has changed quite a bit over the past two decades. A Gallup poll last fall indicated that for the first time a majority of Americans (58 percent) support the legalization of marijuana. And as those numbers continue to rise, the Jeff Spicoli stereotype is giving way to investor types in khakis and crisp shirts.

Advertisement

But not completely. Behind me is a group of burly dudes in baggy shorts and flat-billed hats who look like they could be owners of a head shop. During a break, one of them confesses to me that they “already know the product really well” and are “looking to go legit.”

They have paid $199 each to sit in a small meeting room at the Copernicus Center in Jefferson Park to catch a lineup of legal, medical, and business experts assembled by the MedMen, a Los Angeles–based organization that calls itself “the first and only consulting and management firm in the marijuana industry.” The attendees are hoping these ganja gurus can help them see through the smoky haze surrounding House Bill 1, also known as the Compassionate Use of Medical Cannabis Pilot Program Act, which took effect on January 1, making Illinois the 21st state in the Union to legalize marijuana.

Some came here seeking to open the state’s first-ever dispensaries, the retail stores charged with doling out medical-grade buds. (Allowing time for rules to be finalized and licenses to be granted, the state estimates that these shops could be up and running by early next year.) Others are interested in growing the prized plants. And then there’s the mellow guy sitting next to me with the late-’70s Rick Springfield feathered haircut who came because he had nothing better to do. “I heard about it on a radio show, so I thought, What the hell,” he tells me.

I ask if he’s considering going into the marijuana business.

“I would think anybody would be interested,” he says. “Soon it’ll be like opening a hot dog stand.”

That’s certainly true in Colorado, where marijuana has been legal for medical use since 2001 and for recreational use since January 1. The 637 medical pot shops there now outnumber Starbucks and McDonald’s locations combined. And that doesn’t count the 265 recreational-use stores (as of June 3) that have sprung up, establishing Colorado, unequivocally, as the highest state in America.

But in the Land of Lincoln (a president who is rumored, albeit mostly by pro-weed websites, to have once said he enjoyed a “pipe of sweet hemp”), where the medical marijuana law is one of the most restrictive in the nation, the much-hyped “green rush” of business activity will likely be a trickle. The process of finalizing the rules for Illinois’s medical marijuana program is moving like a stoned tortoise through the administrative obstacle course, but the state has already decided to grant only 60 dispensary and 21 cultivation licenses. Those hoping to score one will have their work cut out for them as they prepare to submit applications, which, according to Bob Morgan, the program’s statewide coordinator, Illinois could start accepting as early as September.

MedMen president Adam Bierman, a slick-looking guy in a pinstriped suit, steps to the podium and holds up a binder the size of a phone book. “This right here,” he says, slamming it down for effect, “is an actual application from the State of Nevada. As you can see, it’s insane.” Prospective potprietors in Illinois will likely need to pull together a similarly fat amount of paperwork, Bierman proceeds to explain, including detailed business plans, security plans, community education plans, tracking systems for every ounce of marijuana harvested or sold, architectural renderings of facilities, tax information, and letters of recommendation.

“For cultivation center applications, it helps to have large-scale agricultural experience,” explains the next speaker, Steven Cooksey, MedMen’s director of licensing. A history of growing wacky tobacco in particular will boost your case—but that experience better not have come in Illinois, because that would be a felony, taking you out of the running. Would-be ganjapreneurs do need plenty of the other green stuff, however, because proof of sizable liquid assets ($400,000 for dispensaries; $500,000 for cultivation centers) is required and there is a hefty nonrefundable application fee ($5,000 for dispensaries; $25,000 for cultivation centers). Once permits are issued, pot businesses must also provide evidence of good-faith money in the form of a surety bond, letter of credit, or escrow account ($50,000 for dispensaries; a cool $2 million for cultivation centers).

Because this is Illinois, other factors could come into play, such as the need to kiss the rings of local bigwigs. At this moment, politically connected lawyers and consultants are scrambling behind the scenes—and charging retainers of up to $10,000—to introduce aspiring cannabis capitalists to local officials and influencers (such as prominent physicians or chamber of commerce leaders) whose support could juice an application. “If you can show you’ve spoken to city officials and there’s some reasonable expectation that you [have support] in that community, it can go a long way,” says one consultant, who requested anonymity so as not to jeopardize the applications of his clients.

Advertisement

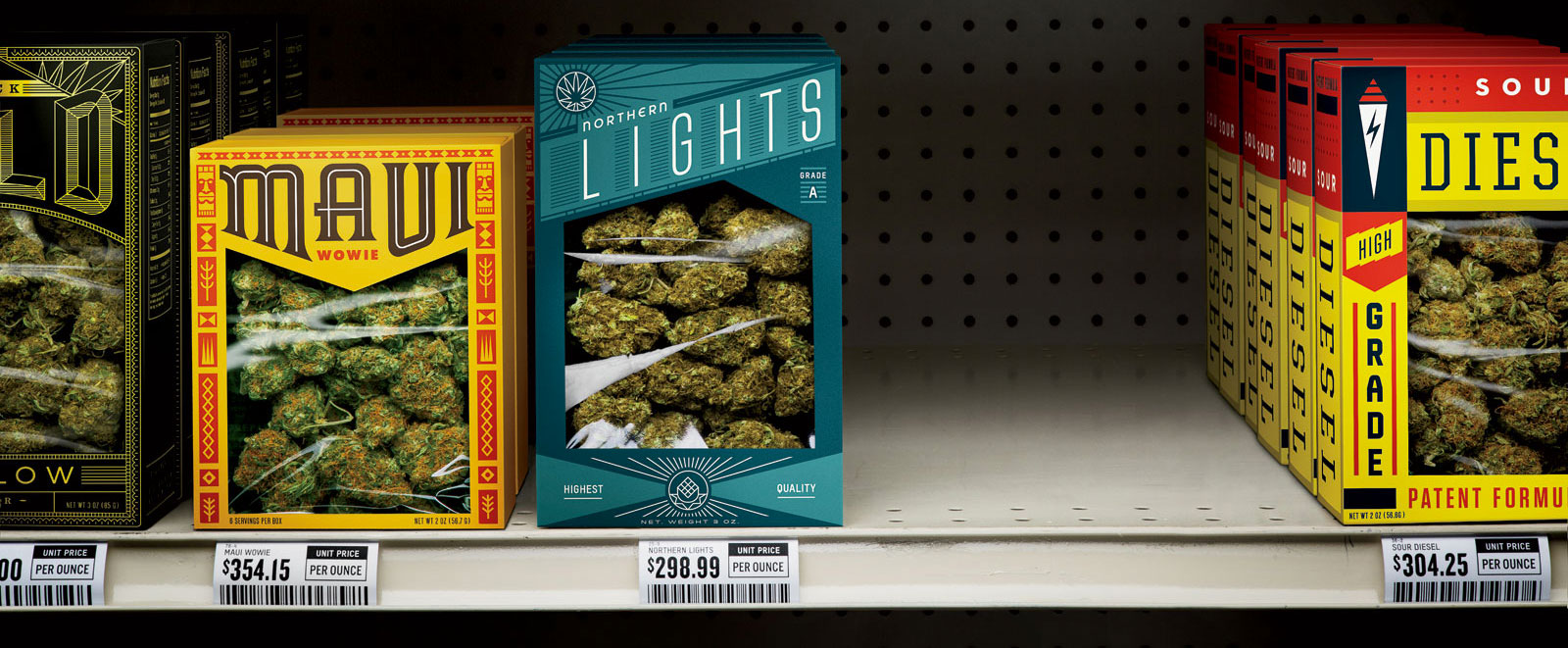

The prize, at least in the early running, is the privilege of legally selling weed (as well as THC-infused edibles such as brownies, cookies, Pixy Stix knockoffs, and gummies shaped like dancing bears) to a remarkably minuscule group of customers. That’s because in Illinois only those suffering from a limited list of conditions—44 as of now, including cancer, HIV, Parkinson’s, rheumatoid arthritis, and, added to the list earlier this summer, epilepsy—will be eligible to buy medical-grade marijuana. (Among other benefits, marijuana can ease

chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, stimulate appetite in HIV patients, and decrease muscle spasms related to multiple sclerosis.)

That might sound like a big pool—each year roughly 65,000 state residents are diagnosed with cancer alone—but consider that many doctors have no interest in prescribing pot and many patients have no interest in using it. And for those who do have an interest, Illinois doesn’t exactly make it simple (more on this later).

Conspicuously absent from the list is chronic or severe pain, the condition cited by the vast majority of marijuana patients in other states. In Colorado, for example, these patients represent 94 percent of the 115,000 approved medicinal users.

In Illinois, the total market is expected to be 10,000 to 30,000 patients, according to Dan Linn, executive director for the Illinois chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, a nonprofit dedicated to legalizing the responsible use of pot. That’s far less than 1 percent of the state’s population.

A Philip Seymour Hoffman look-alike with a gold cannabis leaf pinned to the lapel of his otherwise conservative blue blazer, Linn approaches the front of the seminar room and proceeds to detail the myriad business risks. For a weed advocate, he’s kind of a downer. Because dispensaries aren’t allowed within 1,000 feet of a school or daycare facility and cultivation centers can’t be within 2,500 feet of a school, daycare facility, or residential area, these new businesses will have a tough time finding locations in the most populous parts of the state—including Chicago. (In May, a bill to provide an exemption from those zoning rules for the city failed to pass the Illinois House.) “And there’s no guaranteed return on your investments,” he says. “Remember, you’re breaking federal law every day you’re in this business.”

Advertisement

Federal busts of state-allowed pot operations are rare, and in May the U.S. House of Representatives even voted in favor of an amendment to a federal agency spending bill that would prevent the DEA from targeting such operations. But this legal gray area does create some conundrums. Among them is that federally insured banks cannot accept money from drug-related enterprises (unless, of course, the depositor is named Pfizer). That leaves marijuana entrepreneurs in the dangerous position of carrying around boatloads of cash. Hence the need for detailed security plans that include surveillance cameras and trained guards. In fact, though the scoring system Illinois will use to rate applications is still being finalized, the draft rules show that the state intends to heavily weight strength of security.

Another consideration is that Illinois’s law—unlike any other such law in the nation—authorizes only a pilot program that will phase out after 2017 unless lawmakers vote to continue it. That means entrepreneurial investments made today could go up in smoke tomorrow if the program isn’t made permanent. This is unlikely to happen, though, says Linn: “It’s much easier to keep medicine away from people who have never had it than to take it away from people who have had it.”

But Illinois isn’t exactly making it easy for people to have it in the first place. Patients will need to go through background checks and fingerprinting. They must also provide written certification from physicians to demonstrate a bona fide patient-doctor relationship; this includes proof that they have undergone a physical exam to diagnose a qualified condition and that marijuana could help alleviate their symptoms. If your application is approved, the info will be included in your Secretary of State electronic profile. (Attention recreational users: Cops will be able to verify your “but it’s a medicinal” excuse if you get pulled over on the way home from the Phish reunion show.) As part of their application process, patients will also need to promise not to sell or give away their primo buds.

“Illinois has been really straightforward that it doesn’t want doctors to simply write [medical-use] recommendations for anybody who walks through their door,” says Linn, who also heads his own for-profit company, Midwest Cannabis Consulting, which advises those looking to get into the business. “I think that kind of climate and how it adjusts will really determine the larger success of this program.”

In other words, unless the squares in Springfield loosen up, man, and stop bogarting weed and making legitimately sick people jump through so many hoops, there’s little chance the market will mature enough to support the businesses that get awarded the licenses in the first place.

Those patients who get a thumbs-up to toke will be limited to two and a half ounces of medical-grade ganja every two weeks. And by the way, don’t bust out the growing lamps; unlike Michigan, Arizona, and several other states, Illinois doesn’t allow growing marijuana in your home.

So why is Illinois’s law such a buzz kill? I called Morgan, the program’s statewide coordinator, to find out.

“All of those [restrictions] were intended to create a regulatory environment that, in providing this product in a safe and cost-effective way, does not shock the conscience in terms of security concerns or other moral concerns,” he told me. The state’s pilot program can be viewed as a baby step for lawmakers who support medical and even recreational marijuana legalization and as cover for those hesitant to back an issue that was, until recently, regarded as a political third rail.

“It’s the best law we could pass,” says Linn. “But the most important aspect of this program is helping sick people. The reason it’s so restrictive is because lawmakers were looking at how other states were passing these laws, how they were implementing them, and who was getting access to this product. They thought that was something that was being widely abused. Illinois lawmakers thought [a program like California’s] was making a farce of the idea of marijuana being medicine if someone could walk into an office and pay $100 for a card to have access to the product.”

Translation: Don’t expect to sidestep the rules and find a doctor to say you have glaucoma. To date, at least one Chicago physician has been slapped with an official complaint by the State of Illinois. Brian Murray, who was associated with the presumably well-intentioned Good Intentions clinic in Wicker Park, was accused last December by the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation of prequalifying patients for medical weed without conducting examinations. According to the complaint, Murray told department investigators he “wanted to get a head start” on the new law. (As of June, the case was still ongoing.)

With speaker after speaker laying out all the bummers involved in running a marijuana business, attendees start slipping out. By the end of the seminar, only half remain. MedMen’s Bierman tells me later that this is fairly typical: “Very few people are cut out for this.”

Among those who may be is Joe Sameh, a trim, balding serial entrepreneur from Wilmette, who sat toward the front. He tells me he isn’t daunted by the paperwork, the initial market challenges, or operating within a legal area grayer than Willie Nelson’s beard. One of the few attendees willing to give me his name, the Greek immigrant explains that he’s already launched and sold two successful health care companies, one of which sets up answering services for doctors. When I ask him what kind of experience he has with marijuana, he dodges the question for a second and then answers with a laugh: “I’m 62 years old. Let’s just say I went to Woodstock.”

Advertisement

But his more recent experience with weed—or, rather, his inexperience—is no laughing matter. His wife, Janet, is a cancer survivor who, he says, could have benefited from medical marijuana during her long and painful chemo sessions. Sameh is willing to invest more than $750,000 in his planned dispensary, which would employ five to seven people and be located “somewhere outside the city.”

“We’ve put together a strong healthcare-oriented team,” he says. “Many people are seeing this like alcohol becoming legal some 80 years ago. But we’ll be able to conduct a great deal of clinical research in an area that has really been limited. We see this in terms of how we can improve the quality of patients’ lives.”

He thinks the state’s rigorous requirements are appropriate for any business entering a high-risk nascent industry. “I’d rather see it be a lot simpler. But I understand it. We’re up against people with huge money and huge clout. I just hope the technocrats award the licenses based on merit and not connections.”

The real money, of course, would come from decriminalizing recreational use. According to tax data, after purchasing marijuana became legal this year in Colorado for anyone 21 and older, dispensaries saw $11 million worth of recreational sales in the first four months alone.

Even if Illinois does nothing more in the long run than increase the number of qualifying medical conditions, those entrepreneurs who get in now will have a serious first-mover advantage—though at a significant risk, considering the upfront costs. “If the program doesn’t expand, you’re going to lose that bet,” says MedMen’s Bierman. “But if the program becomes permanent and the list of conditions expands, you’re in an amazing situation. I’ll take that bet every time.”

After the seminar winds down, I strike up a conversation with a lanky guy in jeans who owns farmland in the Rochelle area. He refuses to give his name but says he’s considering applying for a cultivation license. “The cash is going to be tough in the beginning. I don’t know if there will be enough patients to make money,” he says. “But if the industry would open up and you could go after the recreational users, you’d have an advantage compared with those who are sitting on the sidelines. That’s the hope, I guess.”

Adds Linn: “I’d be surprised if [recreational marijuana] wasn’t legal in Illinois in 10 years. There’s too much potential for making money and creating jobs. The opportunities are endless.”

Given the state’s $321 billion debt and dismal credit rating, it could be high time lawmakers seriously consider legalizing reefer. After all, how else are they going to match the millions in tax revenue that this would create? For example, the governor of Colorado—a state whose population is less than half that of Illinois—expects to generate as much as $134 million in taxes and fees from marijuana this fiscal year alone. In light of that, maybe Illinois should think about updating its slogan. How about: “Thank You for Pot Smoking.”

Comments are closed.