Natasha Trethewey’s home is not a bad place to spend quarantine. With its Corinthian columns and neoclassical portico, it looks, on its Evanston corner, like a stately Southern manor — a house perfectly suited to Trethewey, a Southern transplant. The Pulitzer Prize winner and former two-time United States poet laureate is a Chicagoan by way of Atlanta by way of Mississippi.

When I ring the bell in late May, I see a plaque designating the house a historic site; it’s noted for its architect. We sit in her fenced backyard near the raised vegetable gardens, our facemasks set aside once our chairs are 10 feet apart. Listening a week later to the recording I made of our conversation, I'll hear more birdcalls than cars in the background. Add to that the music of Trethewey’s accent; it’s regally Southern, but with tinges of Massachusetts and even her father's native Nova Scotia. When we talk about Tracy K. Smith, she pronounces her fellow poet’s last name with two syllables. The scene is heavenly, and you’d never know how hard Trethewey, 54, has fought to call this place home.

Advertisement

She and her husband, the historian Brett Gadsden, moved to Evanston in May 2017. She was eager to leave Atlanta, where she’d been teaching at Emory University but where she was haunted by reminders of her mother’s murder — the topic of her new book, the memoir Memorial Drive. While the couple had many invitations over the years to other universities, they were waiting for a place they actually wanted to live, a place that felt right. When the opportunity came for both of them to teach at Northwestern University (Gadsden’s doctoral alma mater, a place Trethewey had fallen in love with in the early, long-distance years of their marriage), they embraced the move, found their beautiful historic home, and arrived to spend the summer before the school’s fall quarter started. They were here only six months when fire gutted the house.

It was Thanksgiving morning, and the place was full: Gadsden’s parents and his brother’s family, including an 18-month-old baby, were visiting, as was Trethewey’s younger brother. She was in the kitchen, starting to chop vegetables for that evening. They were fully moved in, but still updating the house. Trethewey’s father, the poet Eric Trethewey, had died in 2014, and she was having a library built in the front of the house to hold the books he’d accumulated over a career writing and teaching at Hollins University in Virginia. The fire started somewhere in that room — from either the lithium batteries in tools the carpenter had left behind or a chemical-soaked rag, or both — and when the smoke alarm first went off, everyone assumed it was due to the bacon and eggs Gadsden’s brother was frying. Soon, though, Trethewey’s mother-in-law noticed blue flames behind the plastic sheet that sealed off the new library and its sawdust; this was a real fire. They had time only to account for all the people and grab the dog, leaving with nothing but the clothes they were wearing. “I didn’t even have my phone,” Trethewey tells me. “I got CVS underwear that night.”

The fire found an almost romantic route: straight up the open grand staircase and down the hall, up more stairs to the third-floor landing outside Trethewey’s and Gadsden’s offices, where the firefighters finally stopped it. The heat melted Gadsden’s computer, but the handwritten pages from Trethewey’s memoir were largely spared — all but the top few sheets, lost to heat and smoke. Trethewey’s brother had been staying in her office, but he was already downstairs; if he’d still been in bed, he’d have been trapped by the climbing flames. And one more stroke of luck: While the house’s interior was destroyed by the fire and by smoke and water damage, the exterior and roof were untouched.

Still, the couple had lost nearly everything they owned. “I don’t think I would’ve understood the devastation of it until it happened,” Trethewey tells me. They moved first to a hotel and then to a rented apartment, where they stayed for the two years it took to restore their home. They moved back in this past November and then, four months later, found themselves on lockdown.

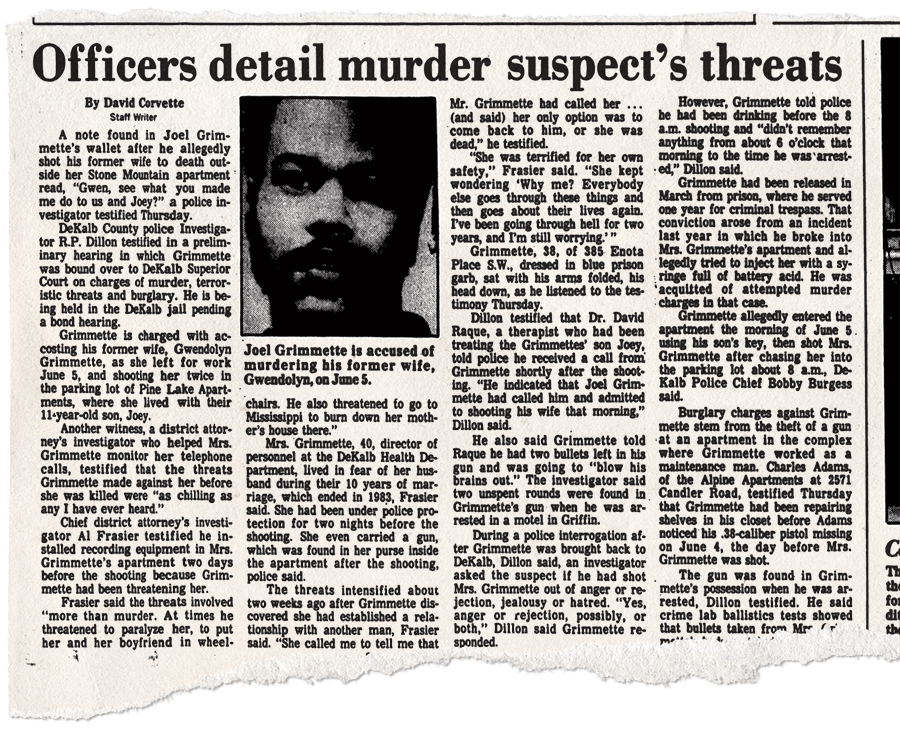

Trethewey’s life has been marked by constant reinvention, by the evolutions she’s undergone to keep pace with both the moves she’s made and the ways her world has moved under her. As she writes in Memorial Drive, there was, first of all, in early childhood, the move from Gulfport, Mississippi, to Atlanta with her newly separated mother, a seismic shift from an idyllic rural life to an urban one. Then there was learning to navigate life with Joel Grimmette, the stepfather who abused Trethewey’s mother physically and Trethewey herself emotionally. Trethewey had gotten out of the home and was finishing her freshman year at the University of Georgia when she got the call that her mother, who had recently managed to divorce Grimmette, was dead; Grimmette had shot her in the parking lot outside her apartment building.

Memorial Drive is about this childhood, and this tragedy, but it’s also about the adult who continues to try to understand her brilliant mother, her mother’s two marriages, her own survival, and the sequence of events that led to the murder. The best memoirs give us a double lens on a life: what it felt like then, and what it feels like looking back. In one passage, an adult Trethewey and a friend visit a psychic; she’s skeptical about contacting the dead, and then questions that skepticism, and then questions the questioning. She looks for meaning in the dates, in the cryptic words the psychic offers. Then she dismantles her hope in those meanings. A poet is not one to simplify grief.

Graduate school took Trethewey to Hollins, where she studied poetry, in part under her own father and her stepmother, and then to UMass Amherst — far from Atlanta and its ghosts. But academic life has a way of washing you up in Nineveh, particularly when you’re half of an academic couple, and in 2001, she began teaching at Emory University in Atlanta and living within walking distance of campus, in neighboring Decatur — far enough that she could avoid the neighborhood where her mother had died, but not far from the DeKalb County Courthouse, where Grimmette had been sentenced. It was a fraught place, and while Trethewey is fond of her time at Emory, she never felt at peace in Atlanta. “I loved my colleagues,” she tells me. “But I knew I wanted to get away the moment I was there. I’d never wanted to go back, but you go back because you have to.”

One night in 2005, Trethewey and Gadsden walked from their home to downtown Decatur for dinner at an upscale restaurant a few blocks from the courthouse. As Trethewey recounts in her memoir, a man she didn’t know struck up a brief conversation and then sent drinks to the table. When Trethewey went to thank him and his wife, he asked if her mother was Gwendolyn Grimmette. He’d been the first police officer on the scene that morning in 1985, and he’d thought about Trethewey’s mother every day in the decades since. Because 20 years had passed since the murder, this was the year when the courthouse would purge the records. The officer was willing to hand everything over to Trethewey. We all have questions about our parents’ lives, but rarely are the answers a matter of public record, and rarely do they come to us so tidily packaged.

A year after she received the bag full of records, she published Native Guard, a poetry collection heavily influenced by the history of Gulfport and the legacy of her mother. That book won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and launched Trethewey into the poetic firmament. Toward the end of her time in Atlanta, she served two consecutive terms as U.S. poet laureate, a post appointed by the librarian of Congress and tasked with raising national awareness of the importance of both reading and writing poetry. (And no, the post has nothing to do with delivering a poem at the president’s inauguration, as many mistakenly believe; that prospect, we speculate in her backyard, would likely have mortified the last three poets laureate.) She delved into essay writing for her 2010 book, Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, which combines poetry, nonfiction, and letters to explore the pre- and post-Katrina history of coastal Mississippi. But in many ways, she’s been working all along toward Memorial Drive, toward a direct reckoning with her own past and her mother’s story.

Even before the chance encounter with the officer in Decatur, her work was often about her mother. Trethewey tells me that a few years after her mother’s death — knowing nothing about poetry, and not having read much of it — she tried to write a poem about her own grief. She laughs, remembering that she wrote the word “sinking" in descending letters down the page. Having only just graduated from college, she showed the poem to her father and stepmother during a visit, and they responded by critiquing it like poets, not like parents. “They tore it to shreds,” she says. Trethewey went upstairs crying, but remembers this as a positive story; they took her seriously, rather than just offering empty praise.

I suggest that maybe she hadn't given herself enough time to process her mother's death before trying to write about it. We’ve been talking, in part, about the undergrads we’ve taught who suddenly feel the urge to write but need to understand how long a journey both craft and reckoning are.

“You can’t just go out and do it because you feel it,” she says. “I had probably been reading E.E. Cummings. I wish I’d at least been paying more attention to Frost.”

Photo: newspapers.com

Photo: newspapers.comMore than three decades after that first poem, in the midst of a tremendous career as one of America’s most lauded poets, Trethewey has delivered the kind of book that can only come from a writer at the height of her powers, a human at the height of her wisdom and pathos.

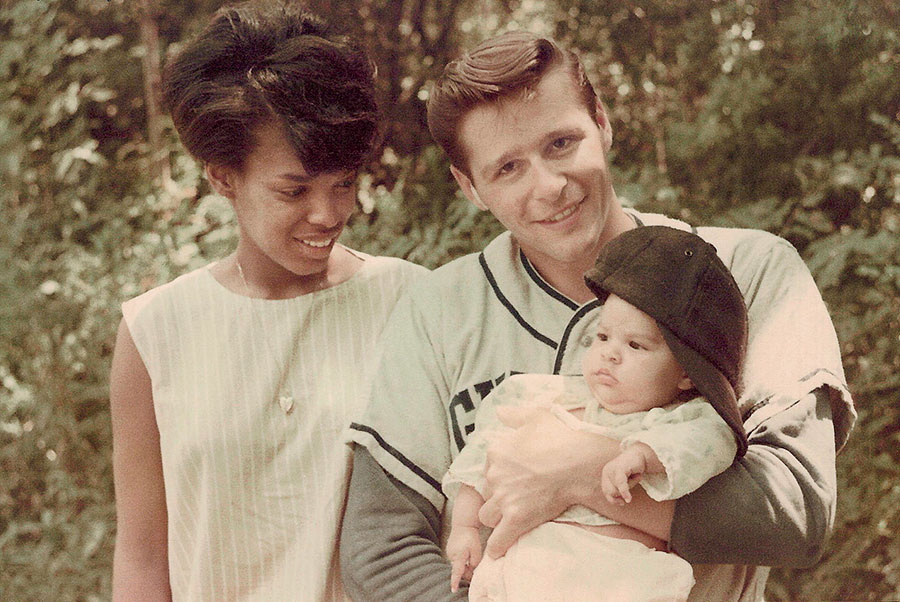

Memorial Drive is not stuck in chronology — it makes liberal use of dreams, of adult insights, and of the actual court transcripts the author came into possession of — but it does trace the outline of Trethewey’s unusual childhood and adolescence. Eric Trethewey came to Kentucky from rural Nova Scotia for college and met Gwendolyn Turnbough in a course on modern drama. When they decided to marry in 1965, they had to elope to Cincinnati, where interracial marriage (he was white and she was Black) was legal; it would be another two years before Loving v. Virginia. Their daughter, Natasha, was born in Gulfport in 1966, on the 100th anniversary of Mississippi’s Confederate Memorial Day. Gwendolyn had to pass a slew of rebel flags to get to the hospital and gave birth on the “colored” floor.

When the couple separated, mother and daughter left Mississippi for Atlanta. There, Gwendolyn met, married, and had a son with Joel Grimmette. She quickly became captive to his rages, threats, and physical violence. This is, mercifully, not the kind of abuse memoir that asks the reductive and victim-blaming question of why someone stayed, and that’s in part because Trethewey is able to take us up so close to the situation that we understand the sway of terror Grimmette held over his wife and her young daughter. Trethewey and I talk about the fact that abusers know subconsciously what they need to threaten and what they don’t. It occurs to me later that this is what she’s tapped into so well: Any reader will understand what both mother and daughter were up against.

After the couple finally divorced, Grimmette fell further into mental illness and made ever more desperate attempts to force his ex to return to him. On the suggestion of the district attorney, Gwendolyn began recording their phone calls and his murder threats so officers could obtain a warrant. The warrant went through late on the night before her murder. The police had been staking out the building that night, but for unclear reasons the officer on duty left early in the morning, giving Grimmette the opportunity to approach.

In Athens, Trethewey was driven to the police station by the officers who’d come to her dorm room; back in Atlanta, she made one return trip to her mother's apartment to gather her things. Later that night, she saw news footage of herself entering the building. “This is where it begins,” she writes in the memoir, speaking of the estrangement between her child and adult selves. “The young woman I’d become, walking out of that apartment hours later, was not the same one who went into it.” She wouldn’t set foot in the building again for nearly 30 years.

She went back to college that fall for her sophomore year. She floundered academically; her GPA sank. But she’d earlier made the UGA cheerleading squad, so when she returned “there were 82,000 of my closest friends every Saturday,” she tells me. (Trethewey and I bond over the fact that there are not a ton of literary writers who were cheerleaders, and fewer who will own it. Both of us were, and do. Both of us came from abusive homes, and both found an anchor in the ritual of forced extroversion and forced smiling that cheerleading brings. It makes a lot of sense to me that this was her tether to normalcy.)

In going back through the records she was given in 2005, Trethewey learned things she hadn’t been privy to earlier. Perhaps most jarring: Less than a week after her mother left her stepfather, Grimmette showed up at a high school football game where Trethewey was cheering. Court records later revealed that he’d had a gun in his pocket, and he’d been prepared to shoot her to punish her mother. Although she was terrified of him, and terrified to see him there, Trethewey took the intuitive step of smiling and waving at him. She learned later that he’d told his psychologist that this kindness was what stopped him from shooting her. But if he had, she reasons, he’d have been arrested and her mother’s life would have been spared. It’s the kind of horrid algebra we do in the years of aftermath.

Among the documents Trethewey came to possess were the transcripts of her mother’s final calls with Grimmette, the ones recorded for the police. We see here his tortuous logic, the ways Gwendolyn attempts to placate him, to talk reason, the ways he derails her again and again. It’s emotionally exhausting just to read them, even after significant editing from Trethewey. She says that the transcripts exhausted her, too. “Every time I got the proofs and I was supposed to go through them,” she tells me, “I couldn’t read that part again. I could read everything else, but I’d skip those.” She wonders if there might be typos in those sections as a result; I assure her there aren’t.

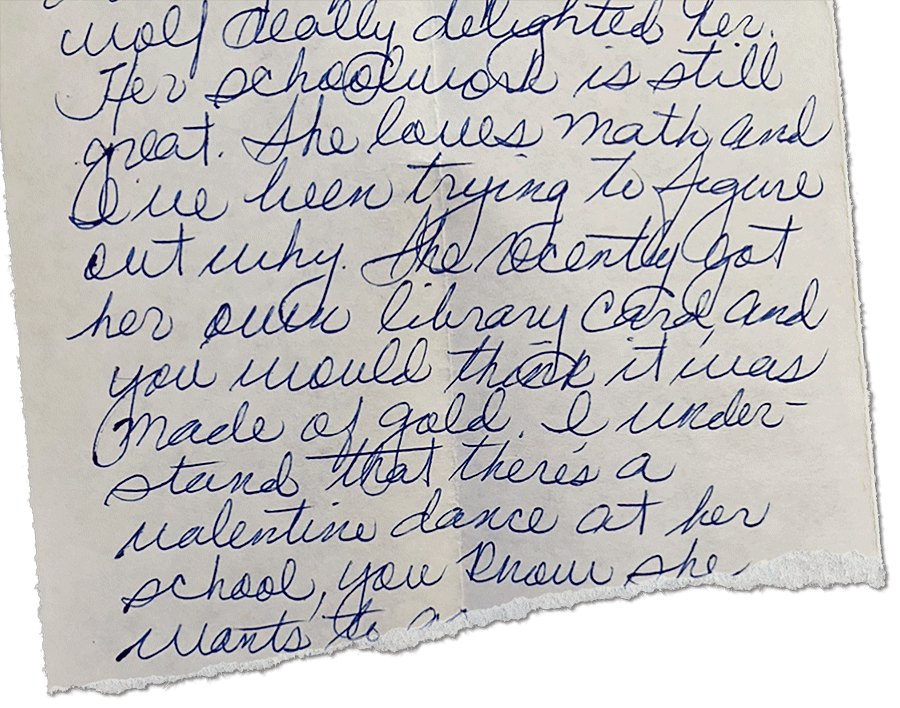

Two of the high points of the memoir are pieces of writing from Trethewey’s mother herself. One is a matter-of-fact police report, following an assault by Grimmette on Valentine’s Day 1984, in which he abducted her and attempted to inject her with something lethal. The other is the beginning of an unfinished document of unclear purpose, perhaps a speech or a thank-you letter, addressed to the shelter for battered women that had helped her toward what looked, at that point, like a safe exodus from the marriage. She was, no huge surprise, a fantastic writer.

Trethewey confesses that she worried about including these documents. “Because it’s not me writing something; it’s me inserting something into the book. But it just didn’t seem like there was any better way to show you who she was. I could tell you, but I wanted people to see her in action.”

I point out another layer to these sections, which is that from a reader’s point of view, not only are we seeing who Gwendolyn was, we’re also reading through Trethewey’s eyes, 20 years after the fact, encountering each sentence as ourselves and also as her, knowing that at the age of 39, she was learning this information for the first time.

Advertisement

These sections contribute to what may be the greatest of this book’s many strengths: the way Gwendolyn herself comes through, not as an empty space defined by the events around her, not as a person diminished by her abuse or by her end, but as herself. Her photo graces the book’s cover, her own writing is powerful, and Trethewey has painted her in all her complexity.

I ask if she’s ready to talk about the book publicly. When she tours for poetry collections, there’s usually just a reading, perhaps a Q&A about craft. But with prose, especially memoir, people will want more of a conversation. They’ll want to ask about everything that wasn’t on the page.

“I’ve been talking about parts of my grief,” she says. The new poems in her 2018 collection, Monument: Poems New and Selected, came out of writing this memoir. “Sometimes I would have to push the memoir aside and something would come out in a poem.” But she knows the conversations around this book will be different. And her relationship to the material is different now, too. “Writing this,” she tells me, “has brought everything up to the surface more. I’ve been much quicker to feel it emotionally when I’m talking about it.”

If Trethewey needed to be in Atlanta to unearth her new material, perhaps she needed the distance of Chicago to finish the book. At the very least, the publication of the memoir and her settling at last into her Evanston home seem cosmically aligned.

Trethewey and Gadsden are here to stay. Maybe they’ll retire to the city, she says, but for now, and at last, this hard-earned suburban haven a few blocks from the Northwestern campus is home. “I cannot get enough of walking on this lake,” she says, nodding east. “[Atlanta] felt landlocked. I’m from the Mississippi Gulf Coast, so seeing a lake that looks like an ocean is great to me.”

I can’t get over the irony of the couple getting their home back just as quarantine forbids them from leaving it. But I also can’t stop thinking about the fire. No one hasn’t imagined that moment, fleeing with only the most essential things, starting again with nothing but yourself.

I’m reminded of a passage from Memorial Drive, one in which Trethewey’s mother, who finally has a plan and the support to leave Grimmette, comes to a teenage Natasha’s room and tells her: “Put everything you want to take with you in the front of your closet and stacked on your dresser. Don’t take the bus home from school. I’ll pick you up.”

Whether a life of upheaval helped make Trethewey a poet, or whether it simply takes a poet to process a life of upheaval, I’m not sure. Sitting in her backyard, I find it hard to believe her life hasn’t always been like this: solid house, bird song, vegetable garden thriving in the late-spring sun.

The only architectural detail inside the house to survive the fire is the living room’s ornately carved wooden fireplace.

In the presence of a poet, I can’t help seeing the metaphor here: The outer shell is the same, and the heart is the same; everything else has been painstakingly rebuilt.

Comments are closed.