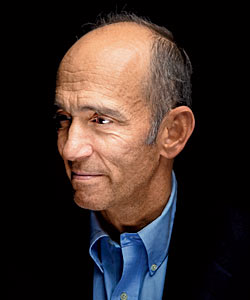

The doctor is in. To reach him, you must cross the limestone-pillared entrance of his headquarters in Hoffman Estates and go past the chocolate-brown paneled walls and soothing tiled lounge, down a labyrinth of hushed halls and empty conference rooms, to the door of a spacious corner office. Two soft knocks and a person instantly recognizable to most any true believer in alternative medicine appears. The doctor is Joseph Mercola, the face, the voice, the prime mover behind one of the nation’s most heavily trafficked—and controversial—natural health websites, Mercola.com.

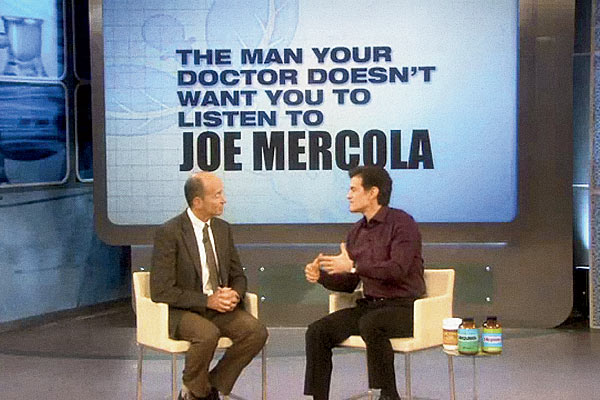

He may not have the mainstream name recognition or rock-star appeal of, say, Mehmet Oz (though he has twice been a guest on The Dr. Oz Show). But Mercola’s influence is nonetheless considerable. Each month, nearly two million people click to see the osteopathic physician’s latest musings on the wonders of dietary supplements and minerals (“The 13 Amazing Health Benefits of Himalayan Crystal Salt”), the marvels of alternative therapies (“Learn How Homeopathy Cured a Boy of Autism”), and his take on medical research, from vaccines (“Your Flu Shot Contains a Dangerous Neurotoxin”) to vitamin D (“The Silver Bullet for Cancer?”).

Visitors to his site are also treated to heavy doses of the contempt Mercola holds for most things traditional medicine and Big Pharma—the “medical-industrial complex,” he calls it. Many followers are almost evangelical in their support of his message. “If only the world had more Dr. Mercolas!” wrote one in the comments section for “The Thugs of the Medical World,” a Mercola.com article about drug companies. “You are a warrior sir, and your tireless, truthful, and fearless efforts to expose these criminals is much appreciated.”

Not surprisingly, the medical establishment sees things differently. Some researchers and doctors say that Mercola steers patients away from proven treatments and peddles pseudoscientific misinformation on topics such as flu shots and fluoridation. In their view, he is resurrecting old myths, such as the threat posed by mercury in dental fillings, and promoting new ones, such as the notion that microwave ovens emit harmful radiation. “The information he’s putting out to the public is extremely misleading and potentially very dangerous,” opines Dr. Stephen Barrett, who runs the medical watchdog site Quackwatch.org. “He exaggerates the risks and potential dangers of legitimate science-based medical care, and he promotes a lot of unsubstantiated ideas and sells [certain] products with claims that are misleading.”

Some of the articles on Mercola’s site, Barrett and others say, seem to be as much about selling the wide array of products offered there—from Melatonin Sleep Support Spray ($21.94 for three 0.85-ounce bottles) to Organic Sea Buckthorn Anti-Aging Serum ($22 for one ounce)—as about trying to inform. (Your tampon “may be a ticking time bomb,” he tells site visitors—but you can buy his “worry-free” organic cotton tampons for the discounted price of $7.99 for 16.) Steven Salzberg, a prominent biologist, professor, and researcher at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, calls Mercola “the 21st-century equivalent of a snake-oil salesman.”

Mercola says that his critics are wrong on all counts. Far from dispensing dangerous misinformation or trading in conspiracy theories, as some allege, he is a champion of “taking charge of our own health,” the doctor insists—a truth teller alerting Americans to what he calls the abuses, hoaxes, and myths perpetrated by the multi-billion-dollar pharmaceutical and health insurance industries.

He’s also undaunted by his recurring run-ins with the Food and Drug Administration. Last March, the agency slapped the doctor with its third warning to stop making what it describes as unfounded claims. Specifically, the FDA demanded that Mercola cease touting a thermographic screening he offers—which uses a special camera to take digital images of skin temperatures—as a better and safer breast cancer diagnostic tool than mammograms. (As of presstime, Mercola’s site had not removed the claims.) Mercola says that the FDA’s statements are “without merit” and has had his lawyers send a letter to the FDA telling it so. The FDA did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Meanwhile, the Better Business Bureau has tagged Mercola.com with an F rating, its lowest, due in part to customer complaints that the company doesn’t honor its 100 percent money-back guarantee. That black mark isn’t exactly the kind of thing that tends to boost revenues. Hoovers, a division of Dun & Bradstreet, estimates that the privately held Mercola.com and Mercola LLC together brought in just under $7 million in 2010. (A Mercola spokesman didn’t dispute that figure.)

But those dollars don’t reflect the extent of Mercola’s influence. According to traffic-tracking firm Quantcast, Mercola.com draws about 1.9 million unique visitors per month, each of whom returns an average of nearly ten times a month. That remarkable “stickiness” puts the site’s total visits on a par with those to the National Institutes of Health’s website. (Mercola claims his is “the world’s No. 1 natural health website,” citing figures from Alexa.com.) Mercola’s 200,000-plus “likes” on Facebook are more than double the number for WebMD. And two of his eight books—2003’s The No-Grain Diet and 2006’s The Great Bird Flu Hoax—have landed on the New York Times bestseller list.

Warrior or quack, straight shooter or charlatan, the question is the same: How has a site built on ideas so contrary to mainstream science—so radical that even some staunch alternative health advocates are uncomfortable with some of his positions—become so popular?

When I met Mercola in his suburban office one afternoon last fall, he was pleasant, articulate, enigmatic, and—understandably, perhaps—wary. Trim and athletic, with the healthy vigor of a marathoner (which he was), the 57-year-old sported a crisp button-down, pressed khakis, and the tan of someone who winters in the tropical climes of the well-to-do (which he does).

His golden hue is but one example of his rebellion against medical orthodoxy. Because scientists have found excessive sunlight to be a likely carcinogen, dermatologists warn that there’s no such thing as a healthy tan. Mercola scoffs, arguing that sunlight is beneficial because exposure to it causes the body to create vitamin D. “I actually never take vitamin D,” he says. “I just get it from the sun.”

He even advocates something considered outright heresy to most skin doctors: the use of tanning beds. Specifically, he recommends the Mercola Vitality Home Tanning Bed—on sale at his site for $2,997 (“Incredible Deal!”), free shipping within the continental United States for a limited time, returns subject to customer-paid shipping plus a 15 percent restocking fee.

Mercola is well aware of his lightning-rod status. He actually embraces it. He did not flinch, for example, when Oz introduced him on a 2011 Dr. Oz show as “the most controversial guest I’ve ever had . . . [a man who] is being called everything from game changer to innovator, controversial to quack.” When I first asked about the mainstream critics who ridicule him, Mercola merely shook his head, as if they weren’t worth discussing.

In fact, he doesn’t need to worry much about being controversial. Not when his in-your-face denunciation of the $2.6 trillion health care industry is resonating so well with an increasingly frustrated segment of the population. With health costs zooming and no convincing plan in place to curb them, “there is public dislike of Big Pharma and many managed care and health insurance companies,” says Tom Smith, director of the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

Mainstream doctors may find it almost inconceivable that people could choose Mercola over accepted schools of thought. But studies show a long erosion of public confidence in medicine, Smith says. Add in the poor economy of recent years and it’s no surprise that people “are looking for treatment alternatives in general and to Mercola in particular.”

The numbers tell the story. Retail sales of vitamins have soared from $2.4 billion in 2006 to $3.4 billion in 2011, according to SymphonyIRI Group, a market research firm in Chicago. Today nearly 40 percent of American adults seek some form of alternative health care, including reiki and ayurveda, the National Institutes of Health says. They are spending roughly $30 billion a year out of pocket for visits to alternative-care physicians and on related products. And the health care industry is taking heed: Some large health insurers now cover certain treatments, such as acupuncture, that were once considered radical.

Mercola isn’t your standard alternative medicine guy, mind you. A spokesperson for the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, a federal agency, declined to comment about Mercola specifically. But she provided position papers that contradict several of his views—for example, on the authority of the FDA and on vaccination (more about that later).

Mercola’s distrust-heavy spin seems to have hit a particular nerve. “That’s the fundamental sales hook,” says Barrett. “That you can’t trust the government, and because I don’t trust the government, you can trust me. And a lot of people don’t trust the government for a lot of reasons.”

Mercola didn’t always stand on the fringes of health care. Early on, he eagerly embraced so-called allopathic medicine—a term that originally referred to the practice of traditional health care but has become a mocking putdown by certain alternative-medicine advocates.

Born and raised in Chicago, Mercola lacked professional role models at home: His mother was a waitress and his father a deliveryman for Marshall Field’s. But, he says, he was “always passionate about learning.”

After graduating from Lane Tech College Prep High School and from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he majored in biology and chemistry, he got a job compounding prescriptions in the pharmacy of a medical center. Next came a degree from the Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine, a small school in Downers Grove. (Unlike an MD, an osteopath, or DO, is trained to focus on prevention and holistic treatment. DOs and MDs are considered equivalent by state licensing boards.)

In 1985, Mercola launched a small private practice out of an 800-square-foot office in Schaumburg. At first, he was a traditional drug-prescribing doctor. He even worked as a paid speaker for a drug company, promoting estrogen replacement therapy. “I thought drugs were the answer,” he says with a shrug.

That changed in the early 1990s, when conventional treatments failed to help a young patient with recalcitrant diarrhea. Flummoxed, Mercola found a possible answer in a book called The Yeast Connection. After he tried the all-natural protocol the book recommended, he says, “the kid had a miraculous recovery.”

Over the next several years, Mercola began networking with a number of like-minded physicians “who were getting pretty good results with nontraditional therapies.” He grew increasingly skeptical of traditional medicine and interested in treatments designed, he says, to “treat the whole person” rather than just symptoms. “I became very passionate about this new approach. I immersed myself in the science of nutrition and found peers who had better results making patients truly responsible for the care of their bodies, teaching them how to do so without writing out a new drug prescription for each office visit.”

In 1997, as a way to share what he had found that would be “useful and helpful,” he started Mercola.com. It proved a hit. But because it didn’t charge for content or accept ads, it was also a money drain. In the first three years, Mercola estimates that he spent half a million dollars on the site. To keep it afloat, he says, “I had three options: to get paid subscribers; to sell information, which I didn’t want to do; or to sell products, which is what I wound up doing. . . . The purpose for selling items is to have a revenue stream so we can pay our staff to provide information to educate the public and make a difference and fund [our] initiatives.”

The success of the site gave a significant boost to his practice, Mercola says: “I had people flying in from all over the world. It always puzzled me: when people came in, I wouldn’t tell them anything different than I had written on the site. They could have just as easily looked it up for free. But they had to hear it from me.” (Mercola stopped practicing medicine six years ago to focus on the website.)

His success also afforded some lifestyle perks. In 2006, for example, he bought a spacious $2 million waterfront home with a pool in tony South Barrington. But Mercola is not one of those bold-faced names who are regularly spotted rubbing elbows with the city’s society set. He has never married and has no children; he does have a girlfriend, he says, but he declines to discuss her.

As he built his site, Mercola began filling it with articles he wrote, on subjects such as his conviction that vitamin D “positively influences” conditions from heart disease to diabetes to cancer. (Some studies do suggest that elevated levels of vitamin D may protect against certain cancers.) He shared his views about issues such as hospital-acquired infections and the overuse and improper use of antibiotics. He reiterated the importance of preventive care and said that spending more time with patients could help them heal. And he recommended eating unprocessed foods and getting plenty of exercise. These are all stances that few mainstream doctors would argue with.

But he also took more controversial positions. On pharmaceuticals, for example: “There are a few drugs—very, very few—that I would recommend.” Among his reasons: Drugs treat symptoms rather than underlying causes, many are unproven, and they can cause immense harm.

“You have more than 100,000 people every year [in the United States] dying from taking legally prescribed drugs,” Mercola says, citing a 1994 study from the University of Toronto. “No people in a typical year are dying from vitamin supplements,” he continues, his voice rising. “And yet vitamins are vilified and drugs are identified as the hero. It doesn’t make sense.” (It’s not unknown for people to die from overusing supplements, which escape FDA review so long as they do not make health claims on the label.)

“Fraud. Kickbacks. Price-setting, bribery, and illegal sales activities,” Mercola rants in a characteristically scathing web posting. “Add in all the doctored and back-dated documents, federal and civil lawsuits, and billions of dollars in government sanctions, fines, and penalties—not to mention the deaths—and you’d think it was the script for a thriller global action movie. But no, it’s just Big Pharma at its deceitful best, dancing all the way to the bank while . . . endangering the lives of regular people like you and me.”

It’s true, of course, that many prescription drugs have been yanked from the market over the years because of serious health risks and side effects. Consider Vioxx, which Mercola says he flagged as potentially dangerous years before Merck withdrew it in 2004 over reports that it raised the risks of heart attack and stroke.

It’s also true that not all drug companies have the cleanest reputations. Just last November, British drug maker GlaxoSmithKline agreed to pay a record $3 billion settlement to the U.S. government over allegations of improper sales and marketing practices involving numerous drugs, including the diabetes medication Avandia. Federal prosecutors also accused GlaxoSmithKline of paying doctors and manipulating research to promote the drug, which has been linked to heart problems.

“There’s no doubt that people die after taking conventional medicine,” Salzberg says. “Those things happen and are bad and should be corrected, absolutely. But the solution is not to believe the claims of Dr. Mercola that because something is natural it’s better. He’s really just changing the topic on you.”

Joseph Ross, a cardiologist and an assistant professor of medicine at Yale University, agrees with Salzberg. “The issue is more complicated than Mercola is making it. Yes, there are problems with the [drug] industry, problems with the relationships between the industry and the profession, and problems with the medical literature due to industry distortions. However, many of the pharmaceuticals available to us today are both safe and effective and are improving the lives of patients. I do not advocate throwing the baby out with the bath water.”

But the stance that tends to drive Mercola’s critics most crazy is his support of the antivaccination movement. A search of Mercola.com reveals dozens of articles and videos railing against virtually all vaccines, particularly mandatory ones for children. Among the titles: “Do NOT Let Your Child Get Flu Vaccine—9 Reasons Why.”

Mercola says he recently donated $1 million to several alternative medicine groups, including the National Vaccine Information Center, which describes itself as a “vaccine watch dog.” Part of the money, according to the group’s website, was used to pay for an ad called “Vaccines: Know the Risk,” which was shown hourly on the CBS Jumbotron in Times Square for several weeks last spring.

Mercola says he is simply trying to ask hard questions about the potential harm caused by inoculations and voice his opposition to government-imposed mandates. “There are virtually no safety studies done [on vaccines],” Mercola says. “We don’t know what the effects of combining them are. We don’t know what the long-term complications are.” He says the government and media downplay very real risks and either underreport or ignore serious adverse reactions. Meanwhile, “we don’t have the option to say no [to getting the shots]. It’s just insane what’s happening, and more and more vaccines [are coming] down the line.”

It’s one thing, Mercola’s critics say, to push unproven dietary supplements. It’s another to advocate that parents shun something that has done so much good. “When I was training 50 years ago, I saw kids who were deaf from measles, demented,” Barrett says. “Vaccines save lives and they prevent disability.”

More broadly, the CDC warns that a major drop in the number of children being vaccinated poses a threat to all Americans. That’s because when a big enough portion of the population has immunity to a certain infectious disease, its spread becomes unlikely—so-called herd immunity. Failure to immunize kids, the CDC says, could result in a return of diseases such as measles and polio that have been all but eradicated.

Mercola is nothing if not a gifted marketer. His site bristles with provocative headlines (“Do Drug Companies Secretly Favor a World Flu Pandemic?”) and promises of astounding breakthroughs (“Zinc Can Cure Diarrhea”). And his enormous archive of blog posts and videos on health care topics from arthritis to shingles are all free—provided you share your e-mail address. At the bottom of such articles are products from Mercola’s own line that correspond to the topics he’s just addressed. “He has applied the science of communication probably as skillfully as anyone who has ever used the Internet,” Mercola’s chief critic, Barrett, acknowledges.

This skill is no accident. Around the time Mercola began to sell products on his site, he also began to study marketing. “I read a lot of books, took a lot of courses, and started understanding the process of how to communicate information effectively.”

Among the tricks he learned was how to grab readers’ attention—the notion, for example, that “80 percent of the effectiveness of an article is based on the headline.” He also learned the power of provocation. “I would find articles that supported one position and [say] why I disagreed. I didn’t hold back, and people seemed to like that. I didn’t realize at the time that was a useful marketing principle.”

If there were any doubt about the importance of marketing to the operation, it was dispelled when I was given a quick tour of Mercola’s sprawling headquarters. The lobby of Dr. Mercola’s Natural Health Center looks like the kind of well-appointed suburban office where you’d expect vanity procedures such as face-lifts to be offered. As it turns out, only one short hallway is dedicated to patient services. “Marketing and customer service take up most of the rest,” a new-patient coordinator told me.

The medical pros on staff—a doctor, a nutritionist, and four therapists—offer treatments such as the Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT), which Mercola describes as a “form of psychological acupressure, based on the same energy meridians used in traditional acupuncture.” Another option: thermography, the screening method with advertising claims that got Mercola into hot water with the FDA.

One key element of Mercola’s appeal—and the reason he is so confounding to some of his critics—is that plenty of the things he advocates are rooted in common sense and even good science. His site, for example, offers a thorough primer on proper hand washing to avoid spreading or catching the flu. As much as he pushes people to spend time in the sun, he also tells them to avoid getting a sunburn and even to cover up in a way that allows enough sun to get through while avoiding skin damage.

In the opinion of David Gorski, a doctor who runs a site similar to Barrett’s (ScienceBasedMedicine.org), the problem is that Mercola either vastly exaggerates preliminary research or cherry-picks studies that bolster his point of view. Gorski believes that Mercola also ignores data that prove him wrong or pushes far beyond what is scientifically sound, using scare tactics to make his point. For example, his site includes an article by a California doctor titled “HIV Does Not Cause AIDS.” Mercola posted a comment at the end of the article: “Exposure to steroids and the chemicals in our environment, the drugs used to treat AIDS, stress, and poor nutrition are possibly the real causes.”

Gorski lists a litany of Mercola’s beliefs that he says fly in the face of good science. “It’s all there,” says Gorski. “He’s antivaccine. He has promoted [someone] who believes cancers are caused by fungus. He has promoted fear-mongering about shampoo. He digs up the hoary old myth that anti-perspirants containing aluminum cause breast cancer. Just this month he is pushing this nonsense that somehow recombinant bovine growth factor in milk causes breast cancer, something for which there’s no evidence.

“Basically, if it’s ‘natural,’ it’s good,” Gorski says. “If it’s pharmaceutical, it’s evil. If anything boils his approach down to a short sound bite, that’s probably as close as I can think of.”

When I asked Mercola why the criticism against him by mainstream physicians is so harsh—and why the FDA has been on his case—he laughed. “It’s a very simple answer,” he says. “There are enormous sums of money involved. There’s this huge collusion between government and industry. They leverage the federal regulatory agencies against us to make us look like we’re breaking the law.”

He pushes treatments and theories shunned by conventional medicine, he says, because “when you understand the truth [you have a duty] to communicate that as clearly and effectively as possible. I can see things that are just obvious and clear to me. I don’t need 30 more years of science to support it. Am I wrong sometimes? Sure. Everyone’s wrong [sometimes]. . . . People call me a snake-oil salesman, of course. They’re free to do that. I don’t think there’s a justification for it.”

As for his critics, Mercola views them as “pawns” of a system in which medical journals have become an almighty arbiter of the scientific process. “It’s how physicians and health care professionals validate their approach,” he says. “Just use the journals. [That’s fine] if you can maintain objectivity and you don’t corrupt it with conflict of interest. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. These journals get corrupted. Then everyone down the line steps in and says, ‘Oh, the journals say it, the experts say it, then who am I to say differently?’ And they all fall in step.”

Salzberg strongly disagrees. “What people like Mercola sometimes ignore is that real medicines really work. They really work because they undergo very strenuous testing. . . . Medical science is constantly critiquing itself. We’re always skeptical about our own results. The purveyors of supplements and ‘alternative medicine,’ including Mercola, are actually not doing that at all.”

In his coolly modern office—with its polished wood floors, caramel-colored leather furniture, and dramatic lighting—Mercola tells me he’s not long for this world. That is, he won’t be sticking around for the coming cold and sunless stretches of a Chicago winter. As is the case every year at this time, he will soon be off to more agreeable latitudes. “I typically go to warm climates such as South Florida, Mexico, Miami, the Caribbean,” he explains. “My girlfriend has a home in Florida, so we stay there sometimes.” He still works every day, he says. “I just work in shorts and T-shirts.”

Of course, he also enthusiastically chases rays. But without traditional sunscreens. Those are “loaded with toxic chemicals,” states a posting on his website. According to researchers, the post continues, “nearly half of the 500 most popular sunscreen products may actually increase the speed at which malignant cells develop and spread skin cancer.”

There is an alternative, a “major breakthrough in all natural sunscreen lotions,” the site says: Dr. Mercola’s Natural Sunscreen with Green Tea. It’s on sale for $15.97 for an eight-ounce bottle, just a mouse click away.

Comments are closed.