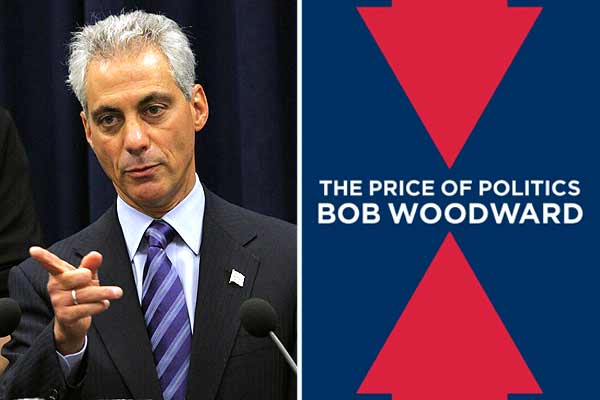

Reading Bob Woodward’s new book, The Price of Politics, this weekend—while the battle between Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Chicago Teachers Union President Karen Lewis raged—I was reminded that the White House Rahm who tried to bully and bulldoze Republicans and Blue Dog Democrats into supporting his boss’s stimulus bill, the healthcare bill, etc., was essentially the same City Hall Rahm who—although not sitting at the negotiating table—was the city’s public face of the ugly lead-up to the ongoing teachers strike.

The Washington Post reporter’s access to the top White House and congressional players is unrivaled, so his picture of Rahm Emanuel—as well as other political figures—in his 17th book is, I'd wager, one of the more accurate out there. Covering three-and-a-half years of the unrelenting fiscal crises of Obama’s administration, Woodward notes that, with some exceptions—Obama and Speaker John Boehner, for example—most of the interviews (and this intricately, intimately reported book relies almost entirely on interviews) were done on background. So it’s not clear that Rahm talked to Woodward, but my hunch is that he did. While Rahm has no trouble turning down interview requests from rank and file reporters, he tends to pay attention to the biggest names. And “Watergate” Woodward—born in Geneva, Illinois, and reared in Wheaton—certainly qualifies.

As Rahm announced Sunday that he would seek an injunction to force teachers back to work (a court denied the request Monday), I kept thinking of the gems about Rahm's time as Obama’s chief-of-staff as reported by Woodward. With Emanuel gone from the White House, at least temporarily, political reporters who write fly-on-the-wall books like this one will have a harder time producing lively copy. The scenes in which he appears are profane, colorful, believable—and better than any political fiction I’ve ever read. Below, some of the best Rahm tidbits from The Price of Politics:

+ Republican congressman Eric Cantor threatened that the president’s first piece of proposed legislation (H.R. 1), the controversial $800 billion stimulus bill, would garner “not a single Republican vote.” Cantor complained that it read, Woodward writes, “like a Democratic spending wish list.” Rahm thought Cantor was “delusional,” and is quoted by Woodward as advising Cantor to keep his “no” Republican votes to himself: “Eric, don’t embarrass yourself.” Rahm ended up being the embarrassed one. Obama got his stimulus bill, but, as Cantor predicted, without a single Republican vote. Woodward quotes Cantor as telling Rahm, “You really could’ve gotten some of our support. You just refused to listen to what we were saying.” The bill was pretty much free of Republican input. Rahm, writes Woodward, responded to such Republican complaints with, “We have the votes. Fuck ’em.” Cantor boasts that Obama (and Rahm) did the Republicans a favor: “…he had unified and energized the losers.” (The Republicans took the House in 2010, and Cantor became Majority Leader.)

+ When discussions with Obama’s Office of Management and Budget Director Peter Orzag and Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, over the formation of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, became bogged down in detail only PhD economists could comprehend, Rahm exploded, “Fucking figure it out.” The subject of the Commission, whose findings were ultimately ignored by the president, raised the temperature of Rahm’s temper. He emailed National Economic Council Director Larry Summers in February 2010: “This does piss me off that we have debated this internally for months ad nauseam…. Our internal process is a fucking debating society.”

+ With Obama’s relations with the business community souring, IBM CEO Sam Palmisano took to calling Rahm. During one call, Woodward writes, Palmisano pointed out that “one provision of the health care bill … would cost IBM about $700 million over 10 years. `You got to understand how we work,’ he explained. ‘My role is to maximize profits. Yours is to get your guy re-elected.’” The IBM chief predicted that the extra cost would result in the layoffs of 20,000 employees. “`What the fuck!’ Emanuel shouted. That’s not going to happen…. What the fuck are you talking about?’ ….`It’s just math,’ Palmisano replied. `Don’t get yourself crazy. Economics is not politics.’” Woodward concludes that Palmisano “believed the Obama White House had a bigger problem. Obama had no chief operating office, no COO to implement his decisions. He had people like Emanuel whose primary focus was Congress. And Obama had Valerie Jarrett and David Axelrod, but they were advisers, and in Palmisano’s view `political hacks’ and `B or C players’ who did not know how to get serious about fixing problems and following through. There was no implementer.”

+ One scene in which Rahm has a background role until he emerges to save the day offers a might-have-been for the teachers’ strike: On the night of January 14, 2010 as the battle over the health care bill continued, the president invited key House and Senate Democrats and their staffers to the White House Cabinet Room. Each chamber had passed a different bill, and the job for them and their staffs was to quickly reconcile them into one. The disagreements were flying: “….House members demanded more spending on prevention and extra subsidies, while senators pressed for Medicaid subsidies….” As midnight approached, Obama was visibly impatient and tired. “Stop this bullshit,” the president said, adding that he’d be willing to “stay here all night to help you, but none of you are listening.” He announced, “I’m going upstairs and going to bed.” With that, he left the room. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi started to gather her papers when Rahm asked her (and the others) to stay, to “humor me” by going over “one more time” the numbers—about $26 billion—that separated the House and Senate. He suggested splitting the difference and went through the numbers like he was teaching a middle school class of not very smart math students—asking them, for example, to tell him the middle compromise number between two and four billion. The lawmakers in the room found Rahm’s lesson “juvenile and insulting,” but Rahm kept going, ignoring “growing protests and derisive comments.” By 1 a.m., when the meeting adjourned, he “had gone through the list and found the middle,” even though the assembled insisted he had accomplished nothing. “Everyone pretty much said that they had not agreed at all, not to any of these arbitrary numbers or alleged compromises.” Rahm responded, “I didn’t say you did,” as he urged them to return the following morning and “we’ll talk about it.” They did, and, with Obama again presiding, Pelosi announced, “Okay, we can do those numbers Rahm wrote down last night.” Senate majority leader Harry Reid agreed, “We can do that.”

Photograph: Esther Kang