Lucy Stoole was wrapped in a flowing rainbow poncho, her hair in Afro puffs, a pink facemask covering her beard. When she removed the mask onstage at the corner of Halsted and Grace, it was to address an assembled crowd of thousands, the attendees of June 14’s Drag March for Change, people who’d been walking in the heat and chanting, “White silence is white violence!” and “Black lives matter!” and “Trans lives matter!” Her anger was pointed and eloquent. “I refuse to be quiet,” she said, “because I’ve never felt peace a day of my life.”

Many things were at a boil: COVID-19 had shut down the bars that the drag community performs in and calls home; the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor had brought lifetimes of frustration to a bursting point; the racism that had been festering in Boystown from its inception was being called out, with people speaking louder about what they saw as racist policing and a racist vibe among bar patrons and staff; and just to be a queer person of color in 2020 was inherently stressful. The speeches reflected all this. Shea Couleé, a Black star of the Chicago drag scene who rose to national prominence on season 9 of RuPaul’s Drag Race, took the microphone: “We built this. I should not have to stand here on a loudspeaker and ask you for fucking permission to walk through the door. Y’all need to hire Black people in your bars. And I’m not just talking about to wipe up your drinks. … I want to see Black people deciding who gets to come in and who gets to make the money.”

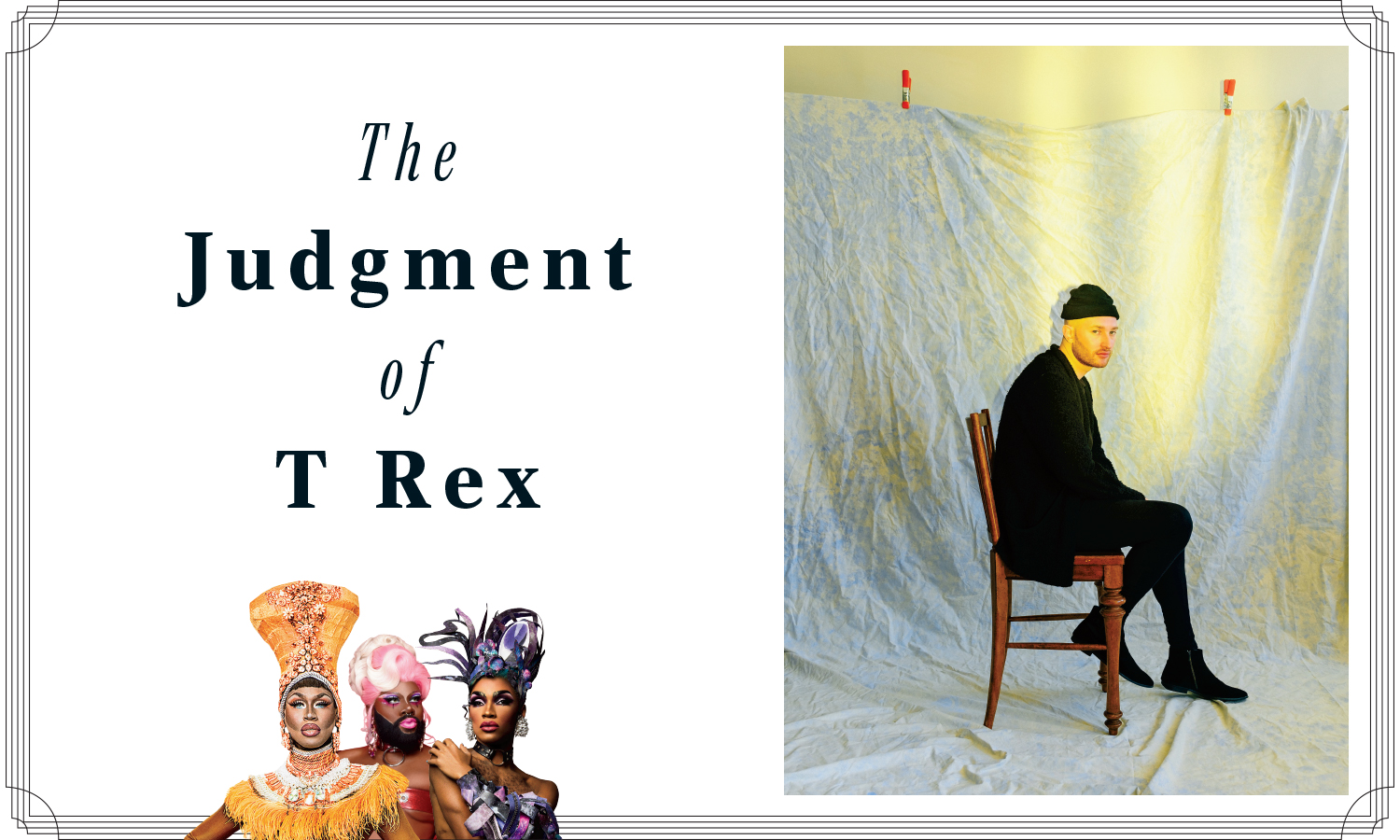

Jo MaMa, a drag performer who organized the march and led it dressed in a powder-blue blazer, spoke last and called out one key figure in Chicago drag by name: T Rex (formerly Trannika Rex), the 32-year-old white queen who hosted, booked, and managed shows at Berlin and Roscoe’s Tavern — including Berlin’s hugely popular Saturday night Drag Matinee — and was widely considered a gatekeeper for the city’s drag scene. Those present remember it as a moment when the floodgates opened.

“There was this huge pink elephant in the room,” Stoole, 36, told me in early August over Zoom. (A note here that although many of the people I’m writing about live in at least two identities, using other names and either he/him or they/them pronouns in daily life, the queens I spoke to all preferred to use their drag names and she/her pronouns for this article. The Lucy I met virtually was out of makeup, her Zoom handle was her legal name, and the only visible sign of drag life was her long, chartreuse nails.) “No one wanted to talk about this one issue, this one person that was such a huge influence. … When Jo MaMa ‘threw the first necklace at IHOP,’ as some of our friends love to say, … that was monumental. For so many of us sitting there, it made us feel like, ‘I can finally say this out loud.’ ”

In the days that followed, more than 50 Chicago drag performers signed an open letter to T Rex, vowing to stop working her shows unless she significantly changed her MO. The letter enumerated microaggressions, talked about double standards for queens of color, and referred to her “dictatorship over number selection.” Among the demands of the letter was that T Rex book more Black performers and trade off Drag Matinee every other week with a Black host. “You have taken a position of power,” the letter stated, “in an art form you rarely practice.” The newly formed Chicago Black Drag Council scheduled an online town hall meeting for later that week. Attendance was presented to T Rex as “mandatory.”

When T Rex (known out of drag as Benjamin Bradshaw) moved to town 12 years ago, drag was in what she calls a dormant period. “There were probably 40 drag queens in Chicago and about 12, 15 who did it on a constant basis.” That’s in contrast to the 100 Chicago drag queens she estimates are working today. “We were all trying to make it a career, but everyone had regular jobs. … It was a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants kind of thing.” When we chatted via Zoom in late July, a few weeks after the town hall, T Rex was subdued, circles under her eyes, a full mustache growing in for the first time in years. The T Rex I’d seen onstage is all energy; this one was like a wind-up toy on its last slow gear turn.

T Rex arrived in Chicago from Fort Pierce, Florida, “with no friends and no family,” but she soon met a drag queen who piqued her interest in the scene, and T Rex started going to Berlin, on Belmont off the main Halsted strip, where Drag Matinee was a long-standing biweekly show. Drag Matinee “was like the alternative, the weird,” T Rex says.

Berlin owners Jo Webster and Jim Schuman, from London and North Dakota, respectively, bought the bar from its original owners in 1994. “The gay community has always thought of it as a straight bar,” says Schuman, “and the straight community has always thought of it as a gay bar.” And indeed, the vibe remains eclectic; on my own visits, I’ve felt more like a ’90s club kid sneaking out than an adult entering a glossy Boystown queer space.

That inclusivity has long been a goal, if not a reality, of Chicago’s drag scene as a whole. Owen Keehnen, a historian of LGBTQ Chicago who has written books about noted local drag queens of yore like the Bearded Lady and Jim/Felicia Flint, says that by the 1960s and ’70s, the drag scene here was fairly well integrated, at least for the time. (Drag in Chicago goes back much further than that, dating at least to the alderman-sanctioned — and alderman-extorted — balls and “masquerades” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.) Bars like the Baton, Sparrows, David’s Place, and Togetherness featured diverse casts. Roby Landers, a Black drag queen, ran shows at the Chesterfield in the ’60s and eventually had a bar of her own, the House of Landers, at 936 West Diversey Parkway, right by the L. (Every time the train passed, she would say, “There goes that bitch again on her roller-skates.”) Those venues frequently got raided, with workers and patrons arrested on charges of disorderly conduct, public indecency, or soliciting prostitution. The shows were, simply by existing, political. “They were a testament to a new era,” Keehnen says. “The LGBTQ community was ready to have fun, and drag shows were an essential part of the party. The politics were about visibility, expression, and declaring the right to do your own thing.”

By the time T Rex started going to Drag Matinee, whatever energy was left from those years was scarcely in evidence at Berlin. The show was drawing small audiences and had a set cast of five that had settled into repeated numbers and “a let’s-get-this-over-with vibe,” she recalls. T Rex was asked to join the cast after her first appearance (“That’s how few drag queens there were”), but with her background in theater and comedy, including classes at Second City, she was more interested in hosting than in performing. After Drag Matinee’s host stepped down following an incident in which she’d made a bachelorette cry, T Rex began emceeing.

Her shtick was Joan Rivers meets Kathy Griffin, quick and foulmouthed and snarky, but joyful. She did shots of Fireball with her performers onstage and joked a lot about drinking (“I’m about to get stepmom-wasted tonight!”). She was not afraid to go edgy: A few years back, when a performer called something “retarded,” T Rex closed in on her as if to scold her and then said, “Um, in 2015 we say ‘retarded-American.’ ” She frequently shimmied and posed and spread her arms wide to accentuate a punch line or welcome laughter. Her style matched the sauced-hostess vibe: She favored bouffants or curly manes, often in shades of red, with bauble rings and ’80s-style jewel tones.

In those early days when she was only hosting, things were still rough. The show, and audience numbers, kept going downhill. Realizing that the show might dissolve, T Rex came up with a proposal to run things. (Drag Matinee exists as a separate business from Berlin, with the bar fronting just $100 to the performers and the host and performers splitting the door money.) In 2013, she dismantled the cast and put a new one together with rotating performers, people she wanted to work with. “No one got bookings unless you brought it every week,” she says. She added a bonus structure to the pay, giving performers incentive to pull people in.

“When I came in, it was very Wild West,” she tells me. “A lot of drag businesses are still like that. I operate better when I know my rules, like ‘Show up at this time.’ I was one of the first people to start a group message the week before the show for everyone to list their songs, because it used to be that you’d just hope people didn’t have your song.” The show got popular enough to go from biweekly to weekly, drawing capacity crowds and a huge roster of performers.

The entire drag world was changing just as T Rex ascended. For one thing, says Schuman, it wasn’t all feminine queens lip-syncing anymore. “There was this change that blended drag with performance art, and that became a new kind of a drag. It wasn’t just about looking like a showgirl, but taking it to a whole new level.”

In 2009 the television phenomenon RuPaul’s Drag Race made its debut, in the wake of which, Webster says, drag has become like a “spectator sport”: “There’s a great fascination for the straight community as much as anybody.” With Drag Race came the possibility of fame, merch, movie contracts, and endorsement deals. Shea Couleé has promoted products by Lush Cosmetics and Goose Island brewery, and she appeared at an Elizabeth Warren campaign booth at RuPaul’s DragCon last year to speak with voters. In the past few years, people like T Rex have been able to support themselves entirely off drag, and performers who go national have the chance to make capital-M money, with some queens netting $10,000 per appearance. DragCon does around $8 million in merchandise sales alone.

In 2013, when The Vixen, a svelte and classically beautiful 29-year-old Black queen from the South Side who became a national name on season 10 of Drag Race, got into performing, T Rex was already a queen of queens in Chicago, and the scene was getting competitive. “Drag Race was probably in its fifth season and had just really popped,” the Vixen says, “and so there was this gold rush mentality. You felt like, ‘If another Black girl gets this spot, I’m not gonna get it, because you only see one of us on every poster, so I gotta get that spot.’ ”

The Vixen had worked her way up through amateur competitions, and her first professional gig was at the Jeffery Pub in South Shore, but she quickly noticed a gap in pay between the Boystown bars and the South Side ones. “As someone who was at the time trying to get on Drag Race,” she says, “I knew that if I wanted to get that attention, I needed to be in Boystown.”

By then T Rex was host, show director, and owner of Drag Matinee, booking talent and making the decisions on order, billing, and pay. Her reputation was spreading throughout the Chicago drag world. She ended up also hosting the show Plot Twist and the amateur competition Crash Landing at Berlin, plus Drag Race viewing parties at Roscoe’s on Halsted. When she wasn’t at the bars, she was on YouTube or doing podcasts. Hers was the picture in the middle of the drag show promotional posters: the red sequined dress, the crimped fire-engine hair, a string of gum stretched from her mouth on one manicured talon.

In 2016, the Vixen did an interview with the Reader in which she spoke about the double standards and the racism that she experienced in the scene. “I think at that point,” she says, “bars became afraid of me, because I had a little media attention.”

On November 3 of that year, days before the presidential election, the Vixen put together a one-time show called Black Girl Magic at Roscoe’s. “I just asked every Black queen that was thriving, ‘Will you help me do a concert?’ Because most of us had not worked together more than once. To have all of us lined up in the dressing room, at our mirrors, was really great,” she says. “I remember all of us consciously not wearing colored contacts that day, and doing things we hadn’t done before to embrace ourselves.” Each performer held down a 20-minute spot, changing onstage, using poems and monologues and dance breaks. The content was political and personal. “As Black queens,” she says, “it was cathartic to finally be able to say these things in front of your community. And I think for the audience, it was eye-opening and gut-wrenching to see our experience played out. I was still onstage when promoters were saying we have to do this again.” The show reconvened that February and became quarterly, then monthly.

In 2018, the Vixen made waves on Drag Race by getting into arguments with several white queens and ultimately walking offstage during the season reunion. Although the conflicts weren’t overtly racial in nature (one was about a borrowed wig), many fans and online commentators understood that the double standards about anger were very much about race. As the Vixen remarked on her fight with white queen Eureka, “Everybody’s telling me how I should react, but nobody’s telling her how to act.”

“A lot of Drag Race queens talk about the racism they experienced on the show after the fact,” the Vixen says. “They talk about it on Twitter after their seasons aired, but I was the first to say it on camera, and that’s a bell you can’t unring.”

As I spoke to the Vixen on July 26, she was doing her makeup, getting ready to film a performance for the online version of Lollapalooza. She writes and performs her own music (her debut album, Commercial Break, was released on August 1, and I’ve had little else on my Spotify since), and she was booked to do 15 minutes. “I’m probably the first drag queen to have their own set at Lollapalooza,” she said.

Advertisement

Stoole, too, has seen her drag life go from hobby to profession. Originally from Kansas, she wasn’t even out of the closet fully when she moved to Chicago 14 years ago, following in the footsteps of a fraternity brother from the small Iowa college she attended. (That fraternity brother became Stoole’s roommate and, eventually, her drag mother, Sophia Sapphire.) Stoole has since gone from ingénue to major force, becoming a mother hen and political organizer in the Chicago drag community. She hosts her own alt-queer show, Fabitat, and is known for being particularly raunchy onstage. She has her own line of pink-and-green sex toys, Stoole Sample. (The Big Mama Stoole is over eight inches long and runs $75.)

Like the Vixen, Stoole says she encountered tokenism in the way shows were booked and promoted in Boystown. “Shows were run and managed by usually white cis people,” she says, “and when they thought about it, they’d add your one Black girl, maybe a Latinx or Asian person. Even when Black people were invited to be a part of shows, you were invited to do the Beyoncé show, the Mary J. Blige show. You weren’t allowed to host; you weren’t allowed to book or run them yourself. You never were put in a position of power.”

Stoole faced the additional challenge of being a nonbinary and bearded queen, a rarity in a scene that, at least when she started, “was not very open to any alternative drag.” Over that Zoom call, she told me, “I’ve always been counterculture. I started in this scene where people were against me for the way I looked, which is something I’ve felt my entire life. So I’m used to working a little harder and being more vocal about why I deserve my spot.” Describing her efforts to rise in the Boystown drag scene, she adds, “It’s really crazy when you think about it in the end. It’s just businesses inside the businesses.”

T Rex, for her part, sees the years leading up to this long, strange summer in a somewhat different light, noting that she did a lot to diversify shows. “That included me booking people that hadn’t hit the stage before at Berlin,” she says, “asking queens who lived on the West Side and South Side, ‘Give me the names of people you would want to see.’ I took it as my responsibility to book the show as greater than what I saw locally in Boystown, which skews very white.” Although the racial makeup of the performers is not the only issue — billing order, pay, and hosting duties would become major points of contention as well — a look at past events suggests that she achieved some balance. At the March 28 edition of Drag Mati-Net, the online version of T Rex’s show, five out of eight queens were people of color, and for the Quarantine Dion show on May 26, it was five out of 10.

Of course, many talent bookers operate according to their own rules and biases. It’s the outsize role of drag within the queer community, and the centrality of T Rex’s shows to that community, that made her selections a matter of such intense public interest and concern. “I don’t think a lot of people are taking into account just how influential in the scene she was,” Stoole says. “As bigger heads in the scene, people come to you and say, ‘What do you think about this person?’ This is someone that with just saying ‘I don’t like this girl,’ that girl wouldn’t get booked anywhere.”

Berlin’s Webster, who has a background in theater, appreciates that T Rex “brought a professionalism to something that was otherwise often in shambles, and managed to tease some of the best work out of some of the artists. … When you’re a fledgling or maybe even an amateur, you don’t necessarily understand what somebody in that position is trying to accomplish.”

T Rex reflects now that her hiring policy was problematically opaque. “Keeping things close to the vest was helpful,” she says, “because I could just say, ‘Oh, we’re not looking for people.’ But in reality I was picking people as I liked them. … More times than not, I was turning down generic white girls, because there’s a surplus. But that silence and those questions eat away at people.”

The town hall meeting on saturday, June 20, happened on Zoom, replete with the glitches and freezes and accidental dragged-out autotuning of voices that we’ve all become familiar with in the past months. Hundreds were in attendance, many making their presence known in the chat box. (As of late September, the recording of the event had been viewed more than 12,000 times on YouTube.)

Lucy Stoole hosted (out of drag but in front of a rack of sequined gowns and feathered boas), and the meeting was moderated by Shimmy LaRoux, a Black female burlesque dancer whose day job is diversity, equity, and inclusion consulting. T Rex wasn’t onscreen for the first half of the three-hour conference — different sections addressed managers at various Boystown bars — but she was clearly at the center of the storm. When she came on in the second half, she was joined by representatives from both Berlin and Roscoe’s.

Although LaRoux issued a stern warning as T Rex entered the call that viewers were not to use the chat box for ad hominem attacks, T Rex told me later that she was shaken to see comments pouring in, many personal. Stoole began by reading the open letter aloud, reiterating the claim that T Rex had reduced “people of color to tokens for your personal gain” and used her influence “to force people out of spaces that we once thought were safe.”

Shea Couleé joined the video call and related two specific incidents: The first took place backstage several years ago at a show called Trannika’s Most Wanted. She remembered T Rex joking that “for Black History Month it would be funny if as a cast we performed to Britney Spears’s ‘Slave 4 U,’ with me dressed as a slave while the rest of you whipped me.” Couleé was the only person of color in the room. “The fact that … I had to almost beg you for an apology really let me know where I stood to you,” she said, “not just as a person, but as a person of color specifically.” The second story involved a night at Drag Matinee when T Rex knowingly introduced Couleé before she was ready, then mocked her onstage for being late, making her look unprofessional. After Couleé spoke up about it, she asserted, T Rex shunned her. “You directly attacked my livelihood, which is an act of violence,” she said. “You blacklisted me in the community until I got on Drag Race, and then … all of a sudden everything needs to be fine. … But even after that, you came for my [drag] daughters. … My daughters are still experiencing these microaggressions.”

Among the perceived microaggressions discussed in the town hall were issues about clothing and music choice. A white queen who signed the letter and spoke to me on condition of anonymity told me that to her, race was only a part of the issue, and she’d been frustrated with T Rex’s management style. “There were so many times that she was like, ‘This is too slow,’” she recalled, “and I would get so frustrated because I felt like she was not tapped into what the audience wanted. … She wanted upbeat, high kicks, things like that. I’ve cried and yelled about it. I know how she treats me sometimes, and if she treats other people like this, then it does need to be brought to her attention.”

At one point during the town hall, Bambi Banks-Couleé, Shea Couleé’s drag daughter, asked T Rex why a performer would be met with “disdain and funny little comments every time she has a gig from Saturday to Sunday in two different venues and is wearing the same outfit, when you have the same show every week, and you don’t even change your outfits. You get paid a lot more than other performers, so there really is no excuse. … Do you plan to hold yourself to your own impossible standards?”

Advertisement

T Rex, who was dressed in a black T-shirt and an upturned visor and had been almost entirely silent up to this point, responded haltingly. “I really don’t have an answer,” she said. “It’s something I’ve spent the last few days thinking about. I have held people to too-high standards, especially for the amount they have to work.”

Zola Chatman, a Black trans woman activist who’d had previous conflicts with T Rex, appeared next. “There is no forgiveness,” she said. “You are done. Have I made myself clear?” She went on to talk to the bar managers present about needed protections for trans people against those who enter queer spaces specifically to harass them. And then her Zoom froze, and she was stuck with her hand emphatically extended toward the camera.

Tatyana Chante, who is nonbinary and queer, read a letter on behalf of drag king Lúc Ami, recounting an incident in which he used stage blood during a Crash Landing competition and T Rex berated him for it while he was still onstage, as directors and producers in the audience watched. “I spent a solid 15 minutes crying in the bathroom afterward,” Chante read from the letter. In the letter, Ami notes that later, someone close to T Rex came to her and excused her behavior by saying that she was drunk at the time.

At the end of the town hall, Stoole asked T Rex to agree verbally to the demands of the letter, and T Rex, who had appeared disoriented and disengaged throughout the meeting, with several on Twitter commenting that she seemed to be checking her phone, struggled to muster a response. Stoole stipulated that as established in a phone call earlier that week — a conversation T Rex said she remembers differently — T Rex was being asked to relinquish not just hosting but managerial and booking duties for two shows a month, a move that would eliminate a considerable chunk of T Rex’s income from Berlin.

The anonymous queen I spoke to, who signed the original letter, told me she was uncomfortable with the new, more stringent terms. “I wish it was more of a conversation,” she said, “but people were angry and rightfully so. The way I saw it was, I signed the letter because we need to have a conversation with her, and she does need to change. I know T Rex and I knew she was willing to change.”

There was a moment in the town hall when it felt like things had come to an impasse, and Stoole reminded T Rex that not agreeing to the letter’s terms meant that no one who signed it would work with her again.

“Then I guess there we are,” T Rex said.

Stoole pushed her: “Can we get an actual yes?”

“Yes.”

The next day, her assent became a moot point when Roscoe’s Tavern announced on Facebook that it had “severed our professional relationship with drag host T Rex, effective immediately.” The day after that, Berlin followed suit, writing, “We are sorry for the part we played in allowing this behavior to remain in our space and we vow to do better.” Soon after, a former employee of T Rex handed over the Twitter and Twitch accounts for Drag Matinee to the Chicago Black Drag Council. The last thing on T Rex’s own Twitter, which had been silent since just before the town hall, was a note of apology. “I’ve spent most of my career as the one holding the microphone,” it stated in part, “and yet it wasn’t obvious to me that other people don’t feel heard — a privilege that I have willfully and blissfully ignored.”

When I spoke to her in July, she was clearly still processing what had happened, trying to pinpoint where things went astray. “There’s no school for owning a drag show,” she said. “There’s no seminar, there’s no human resources department. This is a series of small businesses owned by people who couldn’t get other jobs or just like working in nightlife. I was really good for a really long time. It was so good for so long, and then it was not.”

Among her regrets is not hiring people under her in management positions to ensure that she wasn’t making all the decisions. “I would love to host again,” she said, “but I’m done owning my own business and being the authority, because it’s not fun. The more successful the show got, the more my role became gatekeeper. I didn’t enjoy what my job devolved into.”

When we Zoom again in early September, she’s a lot more animated, looks better rested. Still, she hasn’t been working, is living off what savings she has from her drag career, and doesn’t know what she’ll do next. For now, she’s staying off social media and away from the drag scene, and is having phone conversations with friends from that world — ones she owes apologies to, ones who can help her understand what went wrong. For one thing, she knows that she didn’t react well during the town hall. “I looked like a serial killer,” she says. “I was staring blankly and I couldn’t articulate or show compassion. I didn’t say sorry or anything, because my brain was just off. I didn’t know who was going to confront me or what to be ready for. … I welcome anyone who’s ever put in that position to bring a sentence together.”

In particular, she didn’t expect the Britney Spears incident to come up. “It was 2014,” she said, “and we used to smoke weed backstage and one-up each other on ideas for offensive numbers. … It was a very shitty joke, and something I regret deeply.”

Berlin owners Webster and Schuman, who watched the town hall, have also been reflecting. When I spoke with them in September, Schuman was getting ready for heart surgery the following day. “We’re coming to this as old white men,” he acknowledged. “The town hall meeting came as such a shock to us. It happened very fast. … I spent a good month, a hundred hours, reading everybody from Angela Davis to Cornel West, because I needed to evaluate what was happening. … I mean, our office is down by the dressing room. There was nothing we didn’t hear down there. I had never picked up on anything.”

Stoole has some regrets too. “I think something T Rex is struggling with,” she says, “is the fact that she’s like, ‘Everyone didn’t say this to me when they were working for me.’ … Well, of course they weren’t saying this shit to you. I was working with you and even I wasn’t saying it. That’s something I still struggle with in this situation, how I helped perpetuate this, and that’s something a lot of us still need to unpack and work on, because we can’t let this fucking happen again.”

That’s one thing the Chicago Black Drag Council, formed in the days leading up to the town hall meeting, is invested in. According to Stoole, there are now 10 people in leadership positions on the council, with about 40 additional members; it’s open to Black performers of any kind in Chicago. “It’s a kind of Dumbledore’s Army,” the Vixen says. “It does give me hope because it’s not just a trend; everyone involved is committing to responsibilities and coming up with ideas about how to check in, how to hold bars accountable.”

Lucy Stoole adds, “There’s so much work we need to do, from the smallest thing, which to some people is the booking in this little queer bar in Boystown, to actual statewide policy.”

It might seem like a lot for nightclub performers to take on, but in a sense the present reckoning echoes the 1980s, when the drag community was front and center during the AIDS epidemic, entertaining, raising money, and performing at benefits. “They were on the front lines,” says Keehnen, the historian. And even those activists, he points out, were building on the legacy of an earlier generation of drag queens, like Wanda Lust, the resident DJ at the gay bathhouse Man’s Country in the 1970s. She would dress as a nurse and drive the VD Van, a mobile STD-testing unit, to different neighborhoods, run into the bars, and get people to follow her out; if they did the test, they earned a cookie.

Stoole believes the town hall meeting was a turning point, but online interventions have their limits. “A lot of people have grasped what we were saying and started to implement this,” she says. “And then there are people who, because this was on live, they knew what to say to save their ass, but haven’t been in touch with us at all, haven’t tried to bridge that divide.”

Can T Rex come back into the fold? “If you take these steps,” Stoole says, imagining what she’d say to the ousted emcee, “it can get better, and you don’t have to disappear or stop working.” Then she adds: “Because to be honest, I don’t think they’re a horrible person. I just think that they are struggling with what’s happening right now.”

Perhaps there’s a meaningful irony in the fact that all these seismic changes are coming to the drag world just as the bars have shut down. It’s a chance, certainly, to rebuild from the ground up — and much of that rebuilding is already being done in the online versions of Chicago’s drag shows. Things are expanding beyond what might be feasible in a bar space.

“There’s no capacity limit,” says the Vixen, “so we’ve had up to 3,000 people watching. And there’s no age limit. There are so many drag superfans who are underage, so it’s really a blessing for them. Our audience has just magnified.”

Not only is the Vixen’s Black Girl Magic reaching a global audience (you can catch it monthly on OTV), but she is booking drag queens from around the world. “I have a 17-year-old queen in Paris, I have queens in Lisbon and Africa. It’s a dream come true to take this show almost on a world tour from my living room.” On August 19, attendance for the show ticked up past 500 even as the Vixen was still introducing her first performers. The 28 queens on her virtual stage took full advantage of prerecorded video and digital effects, making for professional-quality editing, rapid-fire costume changes, and impressive backdrops — some real (the city, the beach, the forest) and some not (as when the Vixen appeared to welcome us from the Skydeck at Willis Tower). Bambi Banks-Couleé acted out a whole superhero plot; Lucy Stoole took her performance of Junglepussy’s “Trader Joe” to an actual Trader Joe’s.

Drag kings made an appearance too. (For my money, Switch the Boi Wonder stole the show, doing a simple close-up performance of “Uptown Funk” in 1970s aviators and gold chains.) Anghell from Venezuela, a male burlesque dancer, did a slow pole dance in leather pants outdoors at night. Between performances, the Vixen reminded us to tip the performers via their Venmo and PayPal accounts, fundraised for a queen who was sick, and introduced a piece by DiDa Ritz that was dedicated to the memory of the drag queen Lady Red Couture, who’d died the previous month but, thanks to the magic of video, had been spliced into the performance. Throughout, the chat box was filled with hearts and stars and “GO GIRL GIVE US EVERYTHING” and “love from argentina” and “SUCH A SERVE” and “I won’t even look this good in the afterlife.”

Watching Black Girl Magic in pajamas in my living room, I caught the excitement. And this is just what’s happening on my laptop during a global pandemic. Wait till they’re back in the clubs.