On a blustery morning early in March, Mayor Richard M. Daley was running late for a constituent's birthday party. A very important constituent, practically family: the City of Chicago. One hundred seventy-one years old this year, Chicago was being feted at the History Museum in Lincoln Park, and the second-floor banquet hall was decked out for the occasion—there were hot dogs, balloons, and a cake decorated with the stars and stripes of the city flag. By the time the mayor walked in, 20 minutes behind schedule, the Marist High School Jazz Band was playing an impromptu recital of the school fight song to fill the dead air for the few hundred guests.

Waiting to be introduced, the mayor fixed his windswept comb-over and straightened his blue pinstripes. When it came his turn to speak, he read his prepared remarks in a robotic monotone. Rattling on about the founding father Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable, the city charter, and world's fairs past, the mayor seemed bored—like a man who has spent six long terms schlepping to untold thousands of such ceremonial events.

About halfway through, the mayor paused. Perhaps he sensed his lackluster performance, because he looked up at the audience and started speaking off the cuff. He riffed about the visit he'd made earlier that morning to an eighth-grade class in the tough Back of the Yards neighborhood on the city's South Side—at a school named for his late father, Mayor Richard J. Daley. With passion in his voice, he mused about how many of these young, mainly Hispanic and black students were succeeding in the classroom despite the daily scourge of gangs, guns, and drugs they faced. Then, in one of his characteristic non sequiturs, he segued into a story about the meeting he'd had the day before with the former British prime minister Tony Blair and how the city must meet the vast and varied challenges of the global economy. His face flushed as he stressed the need for safer neighborhoods, better schools, new libraries, and vibrant cultural attractions. His boyish enthusiasm spoke better than words of his love for the city and for a job he gives no indication of ever leaving.

Like father, like son.

Richard Michael Daley, who turned 66 in April, is the country's longest-serving big-city mayor—at presstime, 7,059 days as "The Man on Five" in City Hall. If he serves out the rest of this term ending in 2011, he will have surpassed by four months the 21 years and 8 months his father, Richard Joseph Daley, spent in office before suffering a fatal heart attack. Together, the Boss and Son of Boss have ruled the city for 40 out of the last 53 years and nearly a quarter of Chicago's history. The marks of their tenures are everywhere—from the big stuff like the mass of highways and towering skyscrapers, O'Hare International Airport and Millennium Park, to the smaller things, such as bicycle lanes, wrought-iron fences, and well-illuminated streets.

Over the years, they have inspired many Chicagoans with a feeling that the city works, even when it sometimes doesn't. In the process, their overwhelming popularity with voters has brought stability to a city government that, by tradition, has been politically unruly. (Consider: Chicago went through five mayors in the 13 years between the reigns of Daley I and Daley II.)

But there are other, deeply troubling marks, too: the numerous scars of corruption and scandal; the perpetuation of one-party rule—make that one-man rule; and the ugly results of racism and segregation, which are still felt in the city's downtrodden neighborhoods.

Daley I's legacy is by now more or less a closed book—or a shelf full of books. To many Chicagoans, he was a city savior who kept Chicago from plunging into the downward spiral of urban failure that ravaged other Midwestern industrial cities. To others, he was an intolerant despot who saved only half of the city, the white half. He built lasting monuments, but could not handle the political and social upheaval of his times. The jury is still out on Daley II's legacy. His career, in some respects, has surpassed his father's, and over the years he has both atoned for some of his father's past sins and repeated others. Granted, the two men confronted different generations, different cultures, and different political eras. "It's like comparing A-Rod to Babe Ruth," says the Cook County state's attorney, Dick Devine, who worked as an administrative assistant to Daley I and served as first assistant under the son when the latter was state's attorney.

Our goal here is not to determine who was a "better" or "worse" mayor, but to examine the two administrations across a range of issues to see what the similarities and differences tell us about the men, the city, and ourselves. We tried to focus on areas where there are strong and illuminating contrasts or similarities without delving into the Oedipal complexities between father and son.

In compiling this report I interviewed more than 30 people—from Daley allies and critics (several of whom bridge the father-son generational gap) to former staffers, journalists, and academics. Some of the sources were reluctant to criticize the Daleys too harshly for fear of jeopardizing their relationship with the mayor or with other members of his clout-heavy family.

Daley II himself is fiercely loyal to his father. In March, I met with the mayor in his fifth-floor conference room. He was genial, yet slightly on edge. "I don't compare myself," he said tersely, when asked to line up his mayoral legacy against his father's. As the mayor's youngest brother, Bill Daley, explains it: "You're not going to get a lot of self-psychoanalysis by Rich Daley—neither [would you] with my dad."

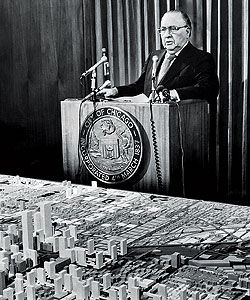

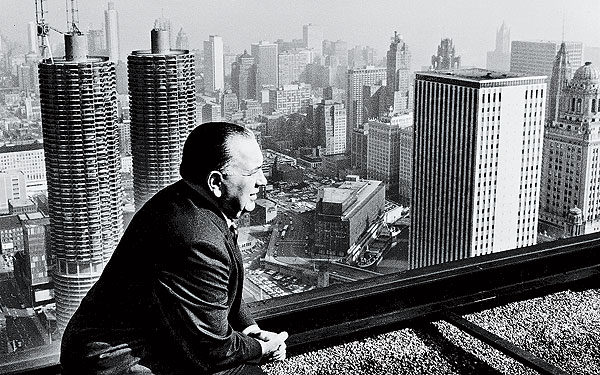

On top of Chicago: Richard J. overlooking his city

POLITICS

The Machine Gets Retooled

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

Early in February, on primary day, I ventured to Bridgeport, the birthplace of mayors. Five of Chicago's 45 mayors, including the Daleys, hail from this roughneck, Irish Catholic-dominated neighborhood at the edge of the old slaughterhouse district. Freezing rain fell as I parked my car at a broken meter (so much for the "City That Works") near the intersection of 35th and Halsted, the heart of the neighborhood's business district. In spite of the bad weather, I half expected the streets to be overflowing with people, as if it were the St. Patrick's Day parade. After all, aren't elections in Bridgeport tantamount to city holidays? But the sidewalks were practically deserted. Ditto for the 11th Ward Democratic headquarters and Schaller's Pump, the old neighborhood tavern that people in the old days used to joke was the "real" City Hall. On election day at the Nativity of Our Lord, the Daley family's former parish, the gymnasium of the church's adjoining school becomes a polling place. A few precinct captains stood outside, and voters trickled in, but not many.

Several poll workers I talked with said they were surprised by the poor turnout. "In the old, old days, everybody would come out and vote—bad weather, good weather, it didn't matter," said one poll watcher at Engine Company 29, where Daley I voted his whole lifetime. The difference owes partly to a change in the neighborhood's ethnic identity. By the time of the 2000 census, Hispanics and Asians outnumbered whites in Bridgeport, and statistically speaking, these ethnic groups have much lower voter turnouts. (Daley II himself moved from Bridgeport to the Central Station development in the South Loop in 1993.) But what about all of the die-hard precinct workers—where were they? "They don't do that as much anymore," said the poll watcher.

Like Bridgeport, Chicago as a whole has changed dramatically in the nearly 32 years since Daley I's death. The stockyards are long gone. The steel mills have vanished. Chicago is no longer even the "Second City"; it dropped to third behind Los Angeles in the 1980s. Huge changes have come to the city's politics, too, simply because of the gradual decline of the Democratic Machine. Sure, Chicago is still dominated by one party—just as most other big cities are today—but not the way it was in the years under Daley I.

* * *

"Organization, not Machine," Daley I would sternly correct people who criticized his vast political operation. "Get that. Organization, not Machine." Whatever you call it, Daley I and his political army counted as many as 35,000 to 40,000 patronage workers who could be relied on to deliver a 400,000-vote margin in each election.

Daley I, of course, did not create Chicago's political machine; Mayor Anton Cermak did it a quarter century before Daley—forging a loose coalition of ethnic duchies ruled by politicians and hoodlums who divided up the spoils with little thought for the public interest. But it was Daley I who turned Cermak's Model T organization into a political muscle car. He changed the existing feudal system, allotting authority to the ward bosses but holding them responsible for taking care of city services and turning out the vote. In return, the ward chieftains surrendered control of the city government to him. Daley I also modernized the machine by cozying up to big business. "He's often thought of as the last of the old-time bosses," says the veteran political consultant Don Rose. "But he was the first of the new-time bosses by bringing LaSalle Street into the Machine."

A consummate politician, Daley I had a Vince Lombardi approach to politics—winning wasn't everything; it was the only thing. It's hard to overestimate how rough-and-tumble the old Machine played. The former 43rd Ward alderman William Singer, one of a handful of independent aldermen who dared to defy Daley I, remembers what happened soon after he was elected to the council in 1969: The ward's Democratic committeeman, Edward Barrett, who was also city clerk, fired a slew of precinct captains from their posts in his clerk's office. "That's how it worked," says Singer.

The slightest dissent was met with swift retaliation. The Reverend Jesse Jackson recalls that if church pastors didn't go along with the pro-Daley ticket or spoke out against the mayor in their Sunday sermons, they could count on building inspectors showing up at their churches on Monday to issue notices of code violations. "Daley's authority was absolute, and people bowed to absolute authority," says Jackson.

To Daley I, however, the Machine was a necessary appendage to municipal governing. "Good politics is good government," he used to say. In addition to delivering votes, ward bosses were also expected to deliver city services 365 days a year. By the end of Daley I's first term, there were 475 new garbage trucks, 174 miles of new sewers, 69,600 new street and alley lights, 72 downtown parking facilities, 2,000 more police officers, and 400 additional firefighters.

As chairman of the Democratic Party of Cook County and the head of the patronage system, he larded city departments with political workers. "No job was too small to get their attention," says the former Illinois governor Dan Walker, who often clashed with Daley I. "They would fight over a janitor job as strongly as they would fight over a cabinet job." A Chicago Tribune investigation in 1974 found that the city had squandered $91 million in its annual budget because of padded payrolls. In Daley I's administration, changing a light bulb was no joke; it required five city workers, according to the paper.

At the same time, Daley I employed some of the city's best and brightest policymakers and technocrats, and if a politically connected city commissioner was a loafer or a drunk, Daley I would make sure he had a competent deputy to run the department. "One of the myths about Richard J. Daley is that he was just a politician," says Paul Green, a political scientist at Roosevelt University. "He loved to govern. He loved to run things."

Bill Daley says his father doled out patronage jobs, not just as rewards for his political supporters, but also to lend a hand to the needy: "My dad would go to wakes, and the widow would be there with a couple of kids, and she'd say, 'I don't know what I'm going to do, Mr. Mayor.' He'd say, 'Call my office tomorrow—we'll see what we can do.'" Today, adds Bill Daley, "you can't do that. You'd go to jail."

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune archive photo

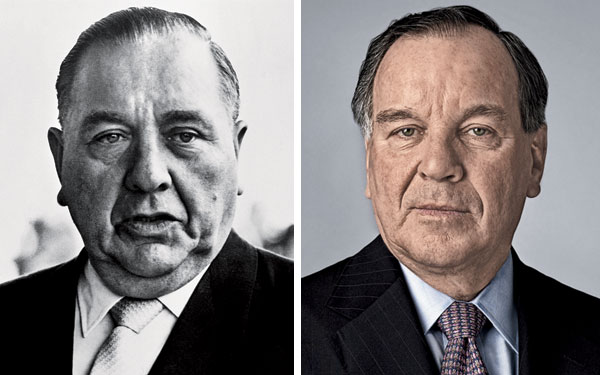

Richard M. in the seat of power

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

By the time Richard M. Daley became mayor in 1989, the Machine of the old days was "dead, dead, dead," as Harold Washington had famously declared. Television advertising had all but replaced precinct captains for attracting votes. As Daley I's longtime press secretary, Earl Bush, noted in the early 1980s, "A bucket of coal won't buy anybody today." Election laws had also changed in the face of the 1979 Shakman decrees, which barred politically motivated hirings and firings.

Daley II did not seek the Machine's Lazarus-like return, and he didn't aspire to be party chairman—leery of the "Boss" stigma that would have come with the title. Asked once by a Tribune reporter why he had not followed his father's blueprint, Daley II was quoted as saying: "Parties aren't what they used to be. People don't vote for parties. They vote for the person. It's all television money and polling now. It's not parades. It's not torchlights and songs." His observation might be even more true today. Does anybody anymore even know who is chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party? (It's Joseph Berrios. Next question: Who the hell is that?)

But Daley II had other reasons for bucking the Machine establishment. It didn't want him. The old guard's loyalty toward Daley I did not extend to the son, especially after the 1983 mayoral race, when the young Daley finished an embarrassing third, and many of his father's old allies blamed the son for splitting the white vote with the incumbent mayor, Jane Byrne, and allowing the relatively unknown legislator Harold Washington to become Chicago's first black mayor. Furthermore, the ward pros saw young Daley as a threat to their power. For his part, Daley felt no loyalty to the Machine. "I don't owe the Democratic Party anything," he was quoted as saying. In 1991, he made the break official when he pushed to change the Democratic mayoral primary to a nonpartisan election.

The split from the old Machine made Daley II more palatable to lakefront liberals and other good-government types, or "goo-goos," who had viewed his father as anathema. "There were a few of us at first," recalls John Schmidt, who had fought Daley I and later became Daley II's chief of staff. "We gave credibility to one another."

But in place of the old Machine, Daley II set up his own independent political organization. He formed groups, such as the now-defunct Hispanic Democratic Organization (HDO) and the Coalition for Better Government, and installed get-out-the-vote workers in every ward who were loyal to him and to candidates who supported him, not necessarily to the full Democratic ticket. Roughly half of the 1,000 or so HDO members were on the public payroll, according to the Tribune.

Beyond running city hall, the mayor has extended his power across the city. He controls at least a half dozen other agencies with taxing powers, including the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Transit Authority, the Chicago Housing Authority, the Chicago Park District, and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District.

His influence stretches further with his family ties. Through his brother John, who chairs the Cook County Board of Commissioners' powerful finance committee, the mayor wields clout in county matters. (The board president, Todd Stroger, was a Daley-appointed alderman before being elected in 2006 to fill his father's shoes.) Another brother of the mayor, Michael, practices law at Daley & George, a clout-heavy law firm. His brother Bill, of course, was commerce secretary under Bill Clinton and is well connected inside the Beltway and in the business world.

Daley II cements his power through his vast influence—or perceived influence—over government levers and funds. Dick Simpson, a political science professor who served two terms as an independent alderman in the 1970s, says Daley II depends on the practice of pay-to-play "pinstripe patronage"—that is, handing out lucrative government contracts and other economic favors to clout-heavy political supporters and campaign contributors.

And just as his father did, Daley II has astutely co-opted nearly all of his opposition. Whereas Daley I's organization relied on patronage hiring to reward the politically faithful and crush opponents, Daley II has dominated the city by doling out the spoils to his opponents. "This is where Richard J. and Richard M. differ," wrote the Tribune columnist John Kass. "Where the Old Man gave critics the back of his hand, the son buys them."

In an interview, Kass, a vocal critic of Daley II, says the current mayor's machine is just as powerful as his father's, but today there's no opposition. "Richard J. Daley had opposition," he says. "The fact is, when his father did controversial things, there was dissent. There's not much dissent anymore, is there?"

Daley II denies that he has created a new Daley machine. "My political organization is myself," he once said. Again, whatever you call it, his mighty political operation would probably put a proud smile on his father's face. "I think Rich didn't say, 'I have to copy what my dad did,'" says Bill Daley. "But he was smart enough to say, 'If it worked for him…'"

* * *

Photograph: AP photo/Charles Rex Arbogast

In March 2003, Richard M. ordered the Meigs Field runway destroyed in the middle of the night.

GOVERNING STYLE

One-Man Rule

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

Northerly Island, the 91-acre peninsula just east of Soldier Field, was eerily quiet one day last winter, the only sounds the crying of gulls and the tranquil Lake Michigan surf. From the narrow strip of lakefront park, the downtown skyline seems a world away. "You can sometimes see coyotes out here," a park district worker told me as I wandered the island.

What's unseen, hidden under eight inches of grassy turf, is the former Meigs Field runway, bulldozed with six gigantic X marks on March 30, 2003, by Daley II's order. For years the mayor had wanted to close the tiny private airport and turn it into a park, but was thwarted by the governor at the time, Jim Edgar. When Daley II finally acted, he did so stealthily at night, and without prior approval from the city council, the state legislature, or even the Federal Aviation Administration. The destruction of Meigs was denounced as an illegal land grab, but the mayor said he acted to protect downtown Chicago from a possible terrorist attack.

The move was vintage Daley II: one-man rule, a governing style taken right out of the Daley family catechism.

* * *

Although you'd hardly know it from most of the last half century, Chicago's charter—in effect, the municipal government's constitution—actually gives the city council vast power over vital city functions. Daley I altered the balance, and his son has followed suit.

Shortly after his election, Daley I wielded the clout behind his double role as mayor and party chairman to undo the civil-service reforms enacted by his predecessor, Martin Kennelly. He wrested control of the budget from the city council, stripping aldermen of their most important function. He also limited the ability of council members to grant routine favors—often in exchange for bribes—such as doling out driveway permits and zoning variances. Bob Crawford, the retired political editor at the news radio station WBBM-AM, says Daley I was simply doing what any good in-charge leader does. He recalls the mayor as once proclaiming, "Show me a mayor who has no power and I'll show you a mayor who doesn't get anything done."

Wearing his two crowns, Daley I had near absolute rule over the city and county governments, the Chicago-area state legislators, and even the judiciary. Inside the Washington Beltway, he was considered a political kingmaker. "Dick Daley is the ballgame," as Robert F. Kennedy famously put it.

Daley I wielded his power untouched by guilt. He thought of himself as a different breed of "Boss": personally honest and civic-minded, unlike the crooked pols of Chicago's past. "My decisions are not what is good for Daley, but what is good for the city," he once told a reporter, and he probably believed it.

In 21-plus years in office, Daley I never lost a vote in the city council. He and his floor leader, the wily 31st Ward alderman Tom Keane, would cut backroom deals and then present them to the full council to rubber-stamp. As the old warhorse Edward Burke, who has served in the council since 1969, once described the role of aldermen in those days: "We were useful to fill chairs and vote the way we were told to vote. That was the extent of it."

Early on, the mayor faced occasional opposition—11 Republicans served on the council in 1955. By the mayor's final term, there was one. (Today, there's still just one: Brian Doherty, of the 41st Ward, on the far Northwest Side.) By the 1970s, 37 of the 50 aldermen had been handpicked by Daley I and afforded him unquestioning obedience. Leon Despres, from Hyde Park, who served 20 years in the council from 1955 to 1975, remained the mayor's most persistent critic. Sometimes Daley I would grow irritated and cut off Despres's microphone in mid-speech. In 1965, the mayor even ordered the council's sergeant-at-arms to force Despres to stop arguing and sit down. As Mike Royko observed: "Until that time the mayor never had an alderman defy him when he said, 'Sit.' In fact most of them not only sit, they bark and roll over." Dick Simpson, a thoughtful critic of both Daleys, says of the father: "The longer he stayed in, the more iron-fisted he became and the more rubber-stamp the council became. That's somewhat true, but not quite the same, with Richard M. Daley."

* * *

On taking office, Daley II quickly tamed the council that had paralyzed Harold Washington. By his second term, the mayor had near lockstep loyalty. A 1978 state law allows the mayor to fill aldermanic vacancies in the council, and since 1989, Daley II has appointed 31 aldermen, including 16 of the current 50. Even with such a solid base of seat-fillers, Daley II, like his father, leaves little to chance. Ed Burke (20th), the council's finance chair, and Patrick O'Connor (40th), Daley II's unofficial floor leader, carry the mayor's water in the council. The former 23rd Ward alderman and city clerk James Laski says Daley II also has city hall enforcers to twist the arms of aldermen to ensure loyalty. "You need a job, you need extra trees cut down in your ward, you need some more money for streets and alleys, or getting funding for a library or a senior center, all those things," says Laski, who recently finished an 11-month prison stint for accepting $48,000 in bribes. "They hold those little carrots in front of you, saying, 'You want dis, you want dat, you want dis—we need dis, dis, and dis.'"

Though Daley II denied it, such horse-trading reportedly took place before the council's recent 33-to-16 vote approving the mayor's controversial plan to build a new children's museum in Grant Park. Afterwards, several aldermen privately told reporters that top city officials had promised them perks and favors in exchange for supporting the mayor.

In the last few years, as corruption scandals have weakened Daley II politically, more aldermen have shown a willingness to confront him, and he has even lost a few votes. The experience seems to have pushed him to wield as heavy a gavel as his father once did. At a council meeting last February, for example, Daley II unleashed a tirade against 2nd Ward alderman Robert Fioretti, who had voted against the mayor's plan to raise the real-estate transfer tax to aid the CTA. (The tax increase passed 41 to 6.) With his fists clenched, Daley II laid into Fioretti: "If Alderman Fioretti believes they don't need the CTA in his ward, then stand and say, 'CTA, bypass my people.'… You'll last about half a day…. They'll have to send 911—police and fire—to protect you and your families." (A video clip of this incident has drawn more than 13,000 views on YouTube. To watch it, search for the terms "Daley" and "rant.")

Bill Daley says that when he saw his brother on the news, he did a double take—thinking for a split second that he was watching his father: "This is déjà vu," he recalls thinking. "He even looked like him, sounded like him. It was almost scary."

* * *

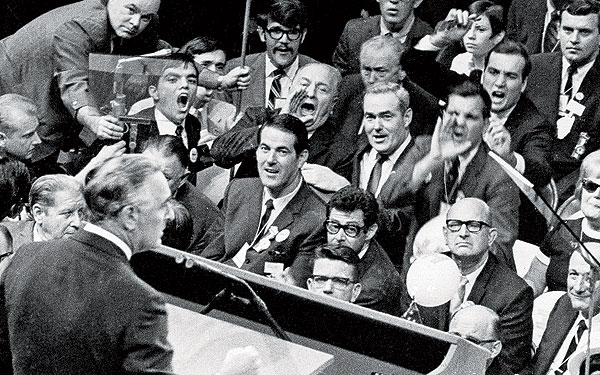

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo by David Klobucar

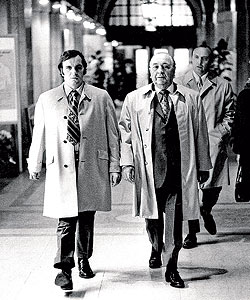

Cupping their hands to their mouths, Richard J. (center) and Richard M. (at right) shout at Sen. Abraham Ribicoff during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

RACE

Searching for Harmony

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

In the early 1960s, a fresh-faced seminary student named Jesse Jackson came to Chicago, and, on the basis of a recommendation from North Carolina's Democratic governor, Terry Sanford, won an audience with Daley I. The mayor was impressed with Jackson and offered him a job—as a toll collector. Jackson wanted something more substantial and instead went to work as a salesman for John Johnson, the publisher of Ebony. "Mr. Daley saw a toll collector, and Mr. Johnson saw a young communicator," Jackson says today.

Had Jackson taken the job, Chicago's most prominent civil rights activist might have been drawn into the Machine—or more precisely, the black "submachine," a vital cog in the Democratic organization. Ostensibly controlled by the long-serving congressman William Dawson, the submachine was actually controlled by Daley I. Dawson and a handful of other black ward bosses doled out patronage jobs and other favors to blacks living in their wards; in return, Daley I carried huge majorities in black precincts at election time. At his peak, for example, Daley I collected 90 percent of the black vote. Timuel Black, the longtime civil rights activist, professor, and historian, coined the phrase "plantation politics" to describe the elder Daley's rule over blacks in Chicago. "The people in the precincts picking the political cotton were overseen by the ward bosses, of which Daley was the head," says Black.

In 1950 Chicago reached its height in population: 3.6 million people. Between 1940 and 1960, a half-million blacks—most of them poor and uneducated—emigrated from the South to Chicago. With this influx, the percentage of Chicago's black population shot up to 23 percent from 8 percent. Meanwhile, whites were fleeing the city—at least half a million during the 1960s. Many of the whites who stayed resisted racial integration through furious NIMBY ("Not in my backyard") campaigns. By 1959 the United States Civil Rights Commission declared Chicago the most segregated big city in the country.

Through the Machine—relying mainly on Dawson and the "Silent Six," the group of black aldermen loyal to Daley I—the mayor managed for years to keep the racial cauldron from boiling over, as it did in other cities. His solution for keeping the city together was to keep it apart via segregation. "Integration didn't help [Daley] politically," says Adam Cohen, an editorial writer for The New York Times who co-wrote (with a Tribune editor, Elizabeth Taylor) the 2000 biography of Daley I, American Pharaoh. As long as the black vote bloc was concentrated and segregated in ghettos, says Cohen, the mayor could more easily control it without scaring off white voters.

But the relative calm didn't hold. After Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination on April 4, 1968, rioting broke out in more than 150 U.S. cities, but the unrest was perhaps worst in Chicago. By the end of three days of chaos, 11 people were dead, 300 had been arrested, and thousands more were homeless. Seeing his city up in flames, Daley I issued orders that have lived in infamy: "Shoot to kill any arsonist" and "Shoot to maim or cripple any looters." (The orders were never actually issued to police commissioner James Conlisk during the riots; rather, the mayor announced them at a press conference on April 15th, a full week after calm had been restored.) Bill Daley defends his father's saber rattling: "He honestly believed that [someone who throws a Molotov cocktail] was putting someone's life at risk that was innocent, and that would justify a shoot-to-maim or shoot-to-kill order. Tell me why this is so illogical."

Logical or not, many people viewed the order as racist. Family, friends, and former staffers insist that Daley I wasn't racist. He was simply a pragmatist who believed at his core that in Chicago, everybody, no matter what race, has an equal opportunity to succeed through hard work, just as he had. "I'm a kid from the stockyards," he used to remind people. If anything, his supporters concede he was a product of his segregated upbringing in Bridgeport.

Others disagree. "Oh, sure he was racist," says his old council foe Leon Despres. "Daley Sr. really was a partisan for segregation." Bob Crawford, the radio newsman who covered Daley I for eight years, is more circumspect: "Some people say 'racist'; I would say, 'somewhat bigoted.' But it all came back to politics with Daley; if anything was too risky, why do it?"

By the late 1960s, Daley I's tight political grip on the black wards had begun to loosen. (By his last election, in 1975, he would receive only half the black vote.) Anger toward Daley I and the Machine swelled up after the deadly predawn police raid in 1969 on the Black Panthers' headquarters that ended in the suspicious deaths of two Panther leaders, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. The tipping point came in 1972, when Congressman Ralph Metcalfe Sr., the former Olympic sprinter and longtime protégé of Dawson, split with Daley I's Machine and joined the chorus of protest after two prominent black doctors were allegedly beaten and harassed by police. "It's never too late to become black," Metcalfe said.

Daley I couldn't adjust. He continued to surround himself with a monolithic group, and he kept blacks at arm's length. "He didn't really have black people in his inner circle," says Cohen. "He had blacks in the submachine, but their responsibility mainly was to turn out votes." Under Daley I, only two blacks headed city departments (health and human services). And it wasn't until 1971 that Daley I slated a black candidate, Joseph Bertrand, to run for a citywide office (treasurer).

* * *

Times were different for Daley II. By 1983, blacks had taken to the streets once again, this time celebrating Harold Washington's mayoral victory. The euphoria was tempered by the "Council Wars," which earned Chicago an embarrassing reputation as "Beirut on the Lake." Mayor Washington died in November 1987, and in 1989 Daley II won the office in the most racially polarized vote in the city's history. "I had whites, blacks both yelling at me," the mayor recalls today. "I'd go to one parade, they'd yell; I'd go to the other parade, they'd yell." He received just 7 percent of the black vote that year.

Much of the black community's hostility stemmed from lingering resentment toward his father. But to the surprise of many, Daley II has calmed the city's political and racial upheavals. "He knew he wouldn't be around long as mayor if he had a racially divided city," says Bill Daley. "And the big concern in 1989 when he won was, 'Will he be fair to the black community?' A lot of people in the black community thought they were never going to get streets cleaned, no snow pickup, no nothing—that Rich Daley would just ignore them."

Within days of being elected, Daley II introduced his new cabinet, and half of the 24 appointees were minorities. By his third term, the African American newspaper The Chicago Defender endorsed Daley II over a black challenger, U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush. "The evidence is clear that the young Daley is much more accepting of blacks than his father was," says Timuel Black. "Maybe it's the times."

Maybe, but it's definitely smart politics. African Americans account for about two-fifths of Chicago's population. This mayor "recognizes something that his old man would've found very, very hard," says the retired federal judge and former U.S. congressman Abner Mikva, who used to clash with Daley I, "and that is that the African American population is not just a piece of a jigsaw puzzle that you fool around with when you're drawing maps and assigning places at the table."

Daley II has set up additional chairs for other minorities, too, particularly Latinos, Chicago's fastest-growing ethnic group. (Latinos make up a quarter of the city's population.) UIC's Dick Simpson argues that the increased role of Latinos in Chicago politics has caused blacks to lose ground. In recent years, for example, the share of city contracts awarded to African American businesses has dropped to 8 percent, the lowest level since Daley II took office.

Still, Jesse Jackson acknowledges that race relations in Chicago are markedly better under Daley II—though much remains to be done. "The city is still the Loop and the Northwest Side," says Jackson. "The South Side, West Side still don't exist."

* * *

Photograph: AP

Richard J. (second from left) tours a new public housing development in 1968.

HOUSING

Undoing the Mess

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

The dismal and familiar story of Chicago's public housing cannot be blamed entirely on Richard J. Daley. By the time he took office in 1955, the CHA had already built a third of the city's 185 public housing high-rises, and 38 other projects were on the drawing board. Until the 1950s, these towers were widely seen as enlightened modernist responses to poverty, not as warehouses for the poor. Abner Mikva recalls Daley I once telling him: "'I'm a liberal. Look at all the public housing I built.' It was almost as if he hadn't kept up with the times. Public housing was a liberal idea—we were all for it in the thirties and forties."

When I asked Daley II about his father's troubled public housing legacy, he got defensive: "He never proposed high-rises." The federal government did, he says. "That was never my dad's idea. It's another myth."

To prove his point, the mayor's office provided me with a copy of a transcript from a 1959 congressional hearing where his father lobbied for federal funding for walkup row houses. But by then, Daley I had already gone forward with what were to become some of the most notorious public housing complexes the country had ever seen: the eight massive towers of Stateway Gardens totaling 1,644 units and the Cabrini-Green Extension—15 mid- and high-rises, totaling 1,925 units—both in 1958. The Robert Taylor Homes, 28 concrete buildings housing 27,000 people, were completed in 1962.

Misguided federal stipulations about rent and benefits soon contributed to driving out employed tenants and married couples. But if Daley I didn't like the federal government's public housing mandates, why didn't he do more to challenge them? "He was a sixties Democrat," explains Bill Daley. "Pump more money into stuff, or get more people jobs. Short-term fixes."

Daley I's critics offer another explanation: His Machine wanted to contain the city's rapidly growing black population within the areas where it already resided, the so-called Black Belt of the South and West sides. "If he would've spread blacks into white neighborhoods, you would've had, literally, riots," says Crawford. "So Old Man Daley saw the value of the high-rises' being able to keep blacks hemmed in, while at the same time they would be easy to control politically by controlling the vote in all of the buildings."

Figures provided by Dick Simpson show that between 1955 and 1971, the CHA built 10,256 apartments—all but 63 in black neighborhoods. "If you look at where the Robert Taylor Homes were placed, where Cabrini-Green was placed, and where some of the other huge high-rises were, they did, ultimately, form a wall between black and white, between poor communities and affluent communities," says Lois Wille, the prizewinning journalist. But Daley I refused to acknowledge a problem. "We have no ghettos in Chicago," he famously asserted in 1963.

The Daley I biographer Adam Cohen argues that "segregation worked for Daley," in the sense that it upheld his political machine and put something of a brake on white flight. "That said, it came at a huge cost to the city. Due in large part to Daley's policies, Chicago is, even to this day, an incredibly segregated city."

Simpson points out that over the past 40 years Chicago has slowly become more integrated. "We've gone from a segregation index of 94 to 82," he says. (The segregation index is used to measure the degree of racial mixing; the highest score of 100 means every city block is completely segregated, either all black or all white; a zero means the races on every block are in exact proportion to their citywide ratio.) "All you can say about it is, it's gotten better."

* * *

By 1995, conditions in Chicago's public housing had fallen into such horrific decay that the federal government had to step in and oversee administration of the projects. At the time, 11 of the nation's 15 poorest neighborhoods were Chicago public housing communities.

Four years later, Daley II took back control—a politically risky but much-applauded move that drew plenty of contrasts to his father. In November 1999, the CHA launched its ten-year, $1.5-billion Plan for Transformation. To date, the city says it has renovated or redeveloped 16,202 public housing units, nearly two-thirds of the total 25,000 units called for in the plan. It is also five years, probably more, behind schedule. A Tribune investigation published in July found that only 30 percent of the demolition and replacement has been completed, and that half of the new public housing units were built before the plan began. In addition, more than 56,000 former public housing residents are still waiting for new replacement homes.

The writer Alex Kotlowitz, whose best-selling book There Are No Children Here chronicled life in Chicago's public housing in the late 1980s, says the Plan for Transformation has increasingly sent Chicago's poorest residents to the bordering suburbs, resulting in a ring of poverty around the city—similar to what has happened in the suburbs of Paris. "On one hand, I admire the audacity of the plan," says Kotlowitz. "On the other hand, I'm not sure it's being implemented well."

Leon Despres says Daley II shouldn't get much credit for tearing down one of Chicago's biggest fiascoes. "This mayor didn't open the gates," says Despres. "Time just did."

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo by Luigi Mendicino

|

THEN AND NOW  |

BUSINESS AND PUBLIC FINANCE

Precarious Prosperity

In 1968, the chairman of Standard Oil of Indiana, John Swearingen, gave Richard J. Daley some bad news: The company had outgrown its South Michigan Avenue headquarters and would move out of Chicago, maybe to the suburbs, possibly even out of state. Daley I got to work. He helped Swearingen buy parcels of vacant land north of Grant Park from the Illinois Central Railroad. Then the mayor rewrote the city's zoning laws to allow a skyscraper to rise 83 stories. In the end, Standard Oil of Indiana put up a $100-million, 1,136-foot-high marble-clad skyscraper, today the Aon Center. For one year it was the city's tallest building, until Daley again used his powers of persuasion to keep Sears, Roebuck in the city. With Sears, Daley I gave the company two city blocks for its tower.

Daley I's fiscal management has been widely hailed as a textbook example of how to run a big metropolitan economy. He was a micromanager who forged strong ties with the city's blue-blooded, typically Republican businessmen while keeping labor unions happy by making sure there were always construction projects with high prevailing wages. The strategy helped him save the city. "The Chicago he inherited in 1955 really was a sleepy town with a downtown that was on the skids," says Adam Cohen. "The Chicago he left behind at the end of his life was much, much grander."

But it wasn't easy. In the two decades he held office, Daley I faced a steadily declining tax base and an economy in transformation. The city's well-to-do and middle class were fleeing to the suburbs, followed by many businesses—manufacturing industries as well as office jobs and retail shops. Faced with a teetering business district, the mayor determined that the city's well-being depended on reinvigorating the Loop. Thus, says the former Tribune urban affairs reporter John McCarron, Daley I "circled the wagons around downtown and helped keep it strong." He pumped fat public works projects into the Loop and spurred private development with flexible tax policies and permissive zoning. Essentially, his goal was to bolster commercial property so the city could boost the tax base and his patronage workers and union supporters could keep their good-paying jobs.

Critics griped that he ignored the neighborhoods—particularly ones in the Black Belt. Consider: by 1965, black unemployment in Chicago had reached 17 percent, well above the rate for whites. "What's good for State Street is good for Chicago, and what's good for Chicago is good for State Street," the mayor insisted.

A crafty administrator, Daley I knew budgets as well as politics. He relied on revenue bonds on top of gradual tax increases to pay for his numerous projects. In his first year in office, he got lawmakers in Springfield to support him in a city sales tax and a utility tax, which became a windfall for the mayor to make city improvements. (In 1970, Chicago got "home rule" status, which allowed the city to impose any kind of tax, except for income taxes, without the approval of the state legislature.)

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

For the first two-thirds of Daley I's reign, the city budget swelled with additional spending—expenditures increased 46 percent during his first term alone—and year after year property and other taxes climbed. Most of the increased spending was for major capital projects and expanded city services, not to mention for the bloated payroll of patronage workers. In 1971, for example, Daley I hiked property taxes by nearly 18 percent. But even as taxes reached levels never seen before, there were few complaints. The mayor's spending binge, says Despres, "created an atmosphere of bustling activity and prosperity," so taxpayers felt that they were seeing their tax dollars at work. "He showed results," says Despres. And when voters started voting down bond issues in the early 1960s—after all, they'd have to pay the interest on the bonds—Daley turned to an agency he had created, the Public Building Commission of Chicago, to borrow money without public approval. The commission became Daley I's "private bank account," says Ross Miller, an English professor at the University of Connecticut and author of the 1996 book Here's the Deal, about the infamous Block 37.

To sustain the boom, the mayor also tapped Springfield and Washington for funds. He got the state to pay the welfare costs of Chicagoans, and Cook County to pick up the tab for the city jails. And when the Chicago Transit Authority was flat broke, Daley I struck a deal with the state legislature to create the Regional Transit Authority, which infused suburban tax dollars into the city's transit system. By 1974, only 15 percent of Chicago's budget financed functions such as mass transit and welfare, compared with 73 percent in New York City, which, by then, was effectively bankrupt. At the height of the Great Society spending—from 1966 to 1970—Daley I helped obtain a 169-percent increase in federal aid for Chicago, according to political science professor Ester Fuchs's 1992 book Mayors and Money. And during his fourth term, Daley I boosted spending by 40 percent without even raising taxes.

If it all sounds too good to be true, it was—as subsequent mayors found out. In the 1970s the city's economy went into reverse. Between 1972 and 1984, the city lost 198,000 jobs, mostly in manufacturing. (By contrast, DuPage and northwest Cook County gained 156,000 jobs.) In addition, local tax revenue stagnated because Chicago was rapidly losing residents. Property taxes, for instance, funded 39 percent of the city's budget in 1970. By 1979, it had dropped to 27 percent. By 1980, the city was in serious financial trouble, and the credit rating agency Moody's downgraded Chicago's bonds.

What happened? When tax revenue slowed and federal and state funds leveled off in the mid-1970s, Daley I and his bean counters began secretly using "revolving funds," a budgetary gimmick of sorts that delayed paying bills, effectively hiding mounting deficits off budget. Meanwhile, the city resorted to borrowing to pay off past debts, but then used the new funds for operating expenses, not for debt repayment—in other words, robbing Peter to pay Paul, all the while maintaining an illusion of solvency. "All of this was swept under the rug under Richard J.," says Lois Wille. "And yet, he always had the reputation of being a good budget man."

* * *

When Daley II took the reins of Chicago in 1989, the city was bleeding a $105-million deficit. He turned it into a surplus by the end of his first term by slashing the city bureaucracy, reorganizing city hall, raising the water and sewer rates, and supporting a 20-percent state income tax hike that boosted school funding. "He's been a relatively good fiscal steward," says Ralph Martire of the taxpayer watchdog Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. Daley II has more or less held the line on property taxes—since taking office, they have increased an average of only 1.5 percent a year, according to the mayor's office. Daley II also cut taxes on businesses, and, like his father, focused much of his attention on keeping downtown Chicago prosperous by aligning with big business. But unlike Daley I, the current mayor has had a lot less state and federal aid (not to mention patronage) to dole out.

Daley II readily admits he's not the fiscal whiz that his father was. During our interview, he marveled at how his father built O'Hare by getting the airlines to handle the operating costs and the federal government to finance 90 percent of the highway costs and development. "He knew a lot more about finance than I did, to be very frank," Daley II said.

Nevertheless, this mayor has held his own, thanks in part to a robust economy for much of his two-decade reign. The growth here of professional service jobs, such as lawyers, accountants, and consultants, has outpaced every other metropolitan area in the country. Housing values have risen by an annual average of 5.4 percent since Daley II took office. Under the mayor, the Loop has flourished, and so have the nearby neighborhoods. New buildings have sprouted up, as have new businesses, including Boeing and MillerCoors, both lured here by the mayor. Between 2003 and 2006, Chicago's diverse economy grew by more than $27 billion. Tourism is thriving. Daley II has helped reinvent Chicago as a destination city, attracting a record 45 million visitors last year, according to Crain's, tying Chicago with Washington, D.C., as the country's eighth most heavily visited city. "Without the mayor, absolutely we would not have this renaissance in arts and culture in Chicago, never," says the city's culture czar, Lois Weisberg. "His father didn't have it, period."

In May, the magazine Fast Company selected Chicago as its "U.S. City of the Year." And in June, Trader Monthly ranked the city as "the world's top trading town," citing Chicago's thriving commodities and derivatives exchanges.

* * *

But the contrasts between the haves and have-nots remain. A 2006 study found that Chicago had lost nearly 600 businesses and more than 14,000 jobs within the city's poorest neighborhoods between 1995 and 2004. Critics say that Daley II, like his father, has focused too much attention on downtown development and not enough on historically underserved neighborhoods. If the city seems more prosperous, they say, that's only because gentrification has expanded to the near South and West sides. "Right now, you go northwest, there's, like, three jobs for every one person," says Jesse Jackson. "If you go south, there're six people for every one job. Here, taxes are up. Services are down. He has not addressed structural inequalities."

Some critics argue that the mayor's controversial use of tax increment financing districts, or TIFs, is a version of the budgetary sleight-of-hand practiced by his father. On paper, TIFs are supposed to freeze property taxes and earmark new revenues for economic development projects in blighted neighborhoods. The TIF, or something like it, is a common economic development tool in cities around the country. But as Ross Miller points out, "Chicago always does it bigger and better." According to the Cook County clerk's office, TIF revenues have grown from $10.6 million in 1989, when Daley II took office, to more than $500 million in 2006.

Urban affairs reporter Ben Joravsky, of the Reader, argues that Chicago's 160 TIF districts—particularly the nine or so TIFs in and around the Loop area—have become a "secret slush fund" for the mayor and aldermen to subsidize private developers (many of them friends or campaign donors to the politicians) in lucrative projects downtown. By Joravsky's count, TIFs suck away more than $500 million a year in property tax dollars that could be spent instead on parks, schools, libraries, and the city's ailing mass transit system.

Mayor Daley and many aldermen defend the use of TIFs as their only tool to spur economic development across the city. "Due to the continued decline in federal and state funding that cities are receiving for capital improvements," Daley says, "TIF has allowed Chicago to continue investing in much needed infrastructure, schools, transit facilities, public housing, streets, roads, and bridges."

The taxpayer watchdog Ralph Martire sees both sides of the argument: "TIFs can be a good tool," he says. "They can also be misused. Because this is Illinois, we get both."

Over the years, Daley II has shrunk the size of city government by privatizing some of its functions—an approach his father, the patronage king, would probably find unimaginable. Daley II started small, first with basic city services, such as towing, building management, and janitorial work. But by 2005 he had leased the Chicago Skyway to an Australian-Spanish consortium for $1.8 billion. Next, he leased four downtown parking garages to Morgan Stanley for $563 million. And he has proposed privatizing the city's parking meter collection and its waste sorting and recycling centers. The big enchilada, though, is Daley II's plan to privatize Midway Airport, potentially a $3-billion-plus windfall. If it happens—the city is currently evaluating bids—it would make Midway the country's first privately operated commercial airport. Martire says Daley II has done a good job so far of keeping his hands out of the privatization-proceeds kitty. "The temptation for a lot of officials," he says, "is to plug the money into their budgets and pay for services with one-time revenue sources. Daley uses the money only for capital projects."

And while his father was strictly Chicago-centric, Daley II thinks globally. Last February, for example, he opened a new city office in Shanghai to woo Chinese industries here and assist local companies doing business in China. Listen to Daley II talk these days and you'll hear a lot of 'China this,' or 'China that'—the mayor knows China's economy is exploding and he wants to make sure Chicago doesn't miss out on the action.

But just as his father faced a drastic economic downturn after 15 or so years in office, Daley II is facing an economy that's sinking with no bottom yet in sight. In Chicago and nationally, home values are dropping, unemployment is rising, and commercial real-estate deals here have dried up. Daley II's legacy may depend in part on whether he can find his way through a tough economy. In February, he pushed through a budget that included a record-breaking $275 million in increased taxes and fees, including $84 million in property tax hikes. (Eleven times in the past 13 years since Daley II took control over the Chicago Public Schools, the board of education has raised property taxes to the maximum allowed by the state's tax limits.) In July, the city's sales tax became the nation's highest.

So far, Daley II has successfully quelled any career-threatening tax revolts. In 2003, when property assessments skyrocketed to 31 percent citywide, the mayor pushed state lawmakers to pass the 7-percent cap on assessment increases. Three years later, he encouraged extending the cap. But in late July of this year, the mayor said Chicago is facing the worst economy of his tenure. "This is a real crisis," he told reporters, adding that the city's budget shortfall was roughly "a couple hundred million."

* * *

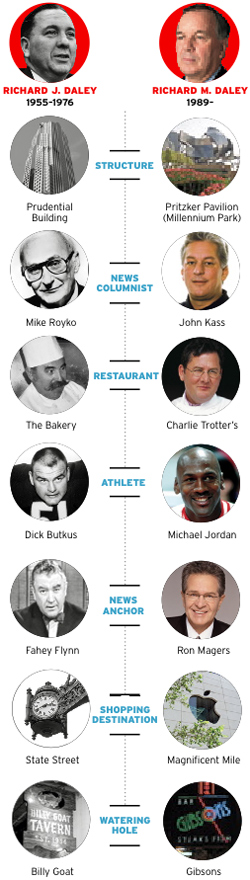

Photography: (Richard J. Daley) Chicago Tribune photo by Arthur Walker, (Richard M. Daley) Kevin Banna, (Pritzker Pavilion) City of Chicago/Mark Montgomery, (Royko and Kass) Chicago Tribune photos, (The Bakery) Chicago Tribune photo by John Bailey, (Trotter) Andreas Larsson, (Butkus) AP photo, (Jordan) Brian Spurlock/US Presswire, (Flynn) WBBM-TV, (Magers) WLS-TV, (State Street, Billy Goat) Kim Thornton, (Magnificent Mile, Gibsons) Megan Lovejoy, (1968 convention) AP photo

|

|

PUBLIC WORKS AND BIG PROJECTS

From Concrete to Wrought Iron

The 94th-floor observation deck of the John Hancock Center affords one of the best views of Chicago. At 1,000 feet high, it also offers a bird's-eye view of some of the greatest hits from the two Mayors Daley. Peer down due east, along the shoreline, and you'll find the James W. Jardine Water Purification Plant (Daley I) located next to a revitalized Navy Pier (Daley II). Looking south, there's the Aon Center and the Sears Tower (both Daley I), and the glistening new Trump International Hotel and Tower (Daley II), currently 90 stories high, but rising to 92 by the time it's completed next year. Also visible is a sliver of Millennium Park's Pritzker Pavilion (Daley II). Beyond the Loop, there's the new Soldier Field (Daley II), as well as McCormick Place (Daley I) with its baby sister, McCormick Place South (Daley II).

From the southwest windows, there's more—including IBM Plaza (Daley I), Chase Tower (Daley I), the United Center (Daley II), and the Stevenson and Dan Ryan expressways (Daley I). Looking north, you'll see the Kennedy Expressway (Daley I) and, off in the distance, O'Hare (Daley I), which seems like just a speck from the top of "Big John," as the Hancock (Daley I) is affectionately called.

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

Few mayors in America have physically changed the face of a city as much as the Daleys have done. Daley I kept Chicago broad-shouldered and brawny with new steel and concrete buildings. Daley II's legacy is the equivalent of a face-lift—beautification projects that have improved the quality of life in the city. As the Tribune's architecture critic Blair Kamin puts it: "Richard J. Daley is the classic modernizer. He's the guy who builds the bones of the city—expressways, bridges, O'Hare. Richie is essentially adding a new layer, Martha Stewartizing the city. His Chicago is a 'City That Plays' rather than just a 'City That Works.'"

And while the Daleys are most closely associated with big projects with high wow factor, they also made sure to focus on the practical nuts-and-bolts of the city—its infrastructure. They knew that if streets weren't cleaned, if potholes weren't filled, if the sewers flooded over, if the water wasn't drinkable, voters would hold them responsible on election day. Their attention to nitty-gritty municipal housekeeping has perpetuated the belief among many Chicagoans that, under the Daleys, the city runs smoothly.

* * *

|

|

When Daley I took over City Hall, the new 41-story Prudential Building was the city's tallest. By the time of his death, Chicago had three of the nation's five tallest buildings: Sears, Standard Oil (now Aon), and Hancock. During his time as mayor, public and private construction in Chicago advanced at a pace of about $400 million a year, reaching an estimated total value of more than $8 billion by his sixth term—the biggest building boom since the Great Fire of 1871. Some of the city's most iconic buildings, including the Inland Steel Building, Marina City, and Lake Point Tower—not to mention all of the Mies van der Rohe-designed modern masterpieces—were built under Daley I.

"The golden age of building happened under Richard J. Daley," says the Chicago architect John Vinci. "Some really good buildings came out of it, some of the best buildings in America." Vinci adds, however, that the city paid a steep price. In Daley I's zeal to remake downtown, he didn't interfere when private developers tore down some of Chicago's prized architectural treasures, including four railroad terminals, a dozen movie palaces, and, most regrettably, the Garrick Theatre and the Chicago Stock Exchange, both designed by Louis Sullivan. "He wanted to show that the city was new and fresh," says Blair Kamin, of Daley I. "The priority was not on saving the old."

Daley I realized that the city had to change to keep up with the jarring shift from a manufacturing to a service economy. He knew that airports were replacing railroads. That office buildings were replacing factories. That commuters were replacing residents. And he built accordingly. McCormick Place secured Chicago's status as the nation's convention capital. The University of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus, which Daley I called his "greatest accomplishment," gave working-class Chicagoans a low-tuition state school near downtown, and in the process, though displacing a large number of residents, revitalized a decaying neighborhood. The opening of the Hancock in 1970 and Water Tower Place in 1975 pumped new retail-shopping life into the stagnant "Magnificent Mile." And O'Hare (1962) brought Chicago a modern airport, ensuring the city would stay the transportation hub of the nation's midsection.

His interest in building large and small—he also built the city's first bicycle paths and neighborhood health clinics—turned out to be good politics. More civic projects meant more patronage and jobs for his labor union supporters. Most of all, says Bob Crawford, when the city looks good—at least, its prominent public places—so does the mayor. "There's a saying that Chicago has a clean face and a dirty neck," says Crawford. "There's a lot of truth to that."

* * *

Photography: (Image 1) Chicago Tribune photo by Jack Mulcahy, (Image 2) Chicago Tribune file photo

Richard J. celebrates his 70th birthday with his four sons, (left to right) Michael, Richard M., Bill, and John.

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

Richard M. Daley, the city's most famous biker, now rides along the same paths his father built, not to mention the 50 miles of new trails and 100 miles of bike lanes that he's added. Like his father, Daley II is a builder. But he has had a more checkered career than Daley I when it comes to handling public works, especially the biggies. In his early mayoral years, Daley II's grandiose proposals—such as the $10-billion third airport at Lake Calumet, the $500-million riverfront theme park with casinos, and the $1-billion downtown circulator trolley—never made it off the drawing board.

Daley II turned his attention to smaller projects. He remodeled bridges, widened sidewalks, planted flowers, repaved streets, demolished dilapidated buildings, and lined the streets with wrought-iron fences. More so than his father, Daley II has pushed his beautification efforts into the neighborhoods, sometimes by thematizing them—the classical-looking columns along Halsted Street in Greektown or the rainbow-ringed sidewalk pylons in Boystown. And unlike his father, Daley II has remade the look of the city while preserving its prized buildings, though critics say it was only belatedly, after a string of high-profile demolitions—including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Arts Club—brought preservation to the political forefront. "When you look at other cities in the U.S.," says Kamin, "he's perceived, correctly, as a leader" in preservation efforts.

Some of his larger projects have been remakes or expansions of existing structures. He pushed through three (much maligned) professional stadium projects: the new White Sox park, the United Center, and, most controversially, the new Soldier Field. In 1996, he enlarged McCormick Place, and he's currently expanding O'Hare, a $15-billion project to add runways and flight capacity. He also revitalized Navy Pier, the Randolph Street theatre district, and the State Street shopping corridor. In 1998, he rerouted northbound Lake Shore Drive west of the Field Museum to create a unified museum campus. Meantime, scores of privately developed residential high-rises and office buildings have sprung up in and around the Loop—a formerly grim expanse of rail yards and warehouses that has been turned into a thriving neighborhood.

Years ago Daley II promised to turn Chicago into the "greenest city in America," and in large part, he's delivered. He has planted 500,000 trees and added more than 200 acres of new parks and green space, including 43 acres of parkland along the river. In 2000, he put up the first municipal rooftop garden at City Hall. Now, the city boasts more than 400 such green roofs, as well as some of the most energy-efficient and environmentally friendly municipal buildings in the country. To Daley II, making the city prettier has a trickle-down effect: Greenery builds community pride, which keeps people and businesses in the city, which keeps the city's economy strong, which reduces crime and poverty, and so on.

Big projects continue to be Daley II's Achilles' heel. The O'Hare modernization project has been mired in corruption, cost overruns, and delays, caused in part by litigation by expansion opponents. For years, Block 37 in the Loop has been a civic joke. "That block was supposed to be paying off now between $30 million and $40 million in taxes a year," says Ross Miller. It's finally turning into a business, shopping, and entertainment center, but a plan to add a "superstation" express-train system to O'Hare and Midway has hit a snag.

Even Daley II's greatest triumph so far, Millennium Park, opened four years late and $325 million over budget. Only by going hat in hand to wealthy civic leaders, foundations, and corporations was he able to recoup about half the costs of the project. But the investment appears to be paying off. The park is now the city's second largest tourist attraction, drawing 3.5 million visitors last year. It has spurred significant residential and commercial development in the East Loop, plus billions more in sales and tax revenues from tourist spending.

Daley II's current big project is the controversial plan to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. The city is one of four finalists, vying with Tokyo, Madrid, and Rio de Janeiro. If Chicago does land the games—and many prognosticators doubt it, but we'll find out in October 2009—parts of the city, particularly areas on the South Side, would be transformed, as would the city's image with the international prestige the games would bring. "Richard M. Daley is sort of the builder for the 21st century," says Dick Simpson. "What he built is not quite all bricks and mortar but a switch in the economy, a change in society, a transformation of the city." Still, Simpson thinks that if Chicago winds up hosting the Olympics, Daley II won't stay in office much past the opening gun: "We will get stuck with a big bill, and I don't think he really wants to handle that."

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo by Jim O ’Leary

SCHOOLS

Remedial Work

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

When the Republicans in Springfield agreed in 1995 to hand over the reins of the city's schools to Daley II, they figured they were setting him up to fail—bigtime. Instead, steady improvements to the school system have become a genuine achievement for this mayor. "Here is the major difference between the two Daleys," says William Singer, who served as Daley II's first school board vice president. "I always felt that Daley the First ignored the public schools. This one doesn't."

In the mid-1950s, the Chicago public schools were badly overcrowded. To accommodate the black families that had flooded into the city after World War II, Daley I and his school superintendent, Benjamin Willis, set up mobile classrooms in the schoolyards of black neighborhoods so African American students—some 25,000 new ones every year—wouldn't transfer to white neighborhoods. Between 1953, when Willis was hired, and 1966, when he resigned, 625 so-called Willis Wagons were put in place. Even so, students attended school in shifts because of the lack of space.

When civil rights groups pressed Daley I and Willis to integrate Chicago's schools, the mayor bristled and generally kept his distance from school affairs. "Richard J. did not get education," says Simpson. "He thought that every kid ought to get an education, but he didn't realize that the public schools really didn't provide that the same way [they did when he was] growing up going to Catholic schools in Bridgeport."

In 1965, the U.S. Office of Education announced that it was withholding $30 million of federal aid because the Chicago school board was still discriminating by race in the schools. Daley I used his clout in Washington to reverse the decision. In 1968, 85 percent of the city's black youth attended schools that were 95 percent black, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare found at the time. (In 1977, after 12 years of negotiating, the federal government and the city agreed to a citywide desegregation plan.)

By the early 1970s, Chicago's schools were in dire straits. More than 40 percent of students weren't graduating from high school. The average eighth grader here was almost a year and a half behind the rest of the country in reading ability, and students in ghetto schools were more than two years behind. And 51 of the 57 public high schools in the city were below the national average in student achievement. "I said repeatedly, 'We're not perfect,'" Daley I told precinct workers in one of his election-eve rallies. "But I will put up against anyone the 27,000 teachers in Chicago—men and women—for their dedication, their devotion, and their interest in the children. And I will put up against any similar city . . . the 500,000 young boys and girls in these institutions. They're just as good as anyone else."

But they weren't, and Daley I was plainly in denial. Says Mikva: "One of the problems the Old Man had was that he would frequently insist that there was no problem."

* * *

Shortly before Daley II became mayor, William Bennett, the U.S. education secretary, called Chicago's public schools the "worst in the nation." When Daley II took control of the schools 13 years ago—the first big-city mayor to do so—he promised things would change. He appointed a new school board and put his former budget director Paul Vallas in charge. Daley II's administration fired 2,000 non-teaching employees, stripped power from the elected school board, ended social promotions, expanded summer school and afterschool programs, and raised taxes to pay for more than $4 billion in school construction and repair. "It was a politically courageous thing to do, because at the time he did it nobody thought there was any upside," says alderman Ed Burke.

The general consensus is that Chicago's schools—many of them, at least—have improved under Daley II. Writing scores are up. So are college enrollment rates for CPS graduates. Last year, nearly two-thirds of public school students met or exceeded standards on the state achievement test. On the ACT, students are making gains at a rate that doubles the rest of the state and triples the national rate. And as of this fall, CPS will have built 77 new schools under the mayor's Renaissance 2010 initiative, which replaces underperforming schools with new ones, some of them privately run. All of this without any crippling teachers' strikes. The last time teachers hit the picket lines was in 1987. Before that, there were nine strikes in 17 years.

The achievement gap is still a chasm for many. Fewer than half of CPS high-school students graduate, and dropout rates remain high. Except for a small but growing handful of high-performing schools, most CPS schools are still lagging behind their counterparts in the suburbs. School funding remains a big problem.

Even so, Daley II's efforts on education have earned him grudging respect even from his detractors. "The schools are still a terrible problem—they still suffer from segregation," says Leon Despres. "But this mayor has permitted—welcomed—experimentation, different kinds of schools, charter schools, special merit schools. The mayor deserves credit for that."

* * *

SCANDAL AND CORRUPTION

See No Evil

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

As mayors, both Daleys have maintained a pristine record of personal honesty. At the same time, ample instances of skullduggery, graft, and scandal have marred their administrations without sinking them. It's as if there were a long-standing—if tacit—pact between Chicago's voters and its pols: As long as officeholders deliver dependable city services, it seems, citizens will return the favor at the ballot box while tolerating the greasy wheels of politics. "There's corruption under every mayor," says Roosevelt's Paul Green. "Chicago is a tough city. It isn't Madison, Wisconsin." Many of the streets you drive on, Green says, are named for people "you wouldn't want to be in a lifeboat with, if they were alive."

By several accounts, Daley I candidly tolerated a certain level of graft as part of his management style. Leon Despres says that the mayor once told a group of University of Chicago professors, "I let them go so far and no further," referring to his Machine allies. "Daley wasn't given to preaching," Royko once wrote. "His advice amounted to: Don't get caught." Much to the mayor's chagrin, many people did—from average-Joe precinct workers to close friends and members of his inner circle, including alderman Tom Keane and the mayor's patronage chief, Matt Danaher.

Publicly, anyway, Daley II denounces corruption. When graft charges touch the current administration, he typically decries the problem, though he defiantly insists he knew nothing and blames the trouble on a few bad apples. Often, he rolls a few heads and then announces reforms that never seem to go far enough to cure the problems.

Though the scandals tarnishing the two administrations echo each other in many ways, they are also quite different. Many of Daley I's problems, for example, sprang from election-related corruption—cries of vote fraud rang out after every election, not a major issue today. And though patronage excesses were rampant under Daley I—"As corrupt as the city's hiring practices may be today, they're clean and pure compared to the old days," says Lois Wille—they weren't necessarily illegal at the time.

In 1969, Michael Shakman, a Hyde Park lawyer, sued the Democratic organization, claiming he had lost his bid to become a delegate to the state's constitutional convention in large part because of political patronage. Three years later Daley I and the Shakman plaintiffs reached an agreement that set strict limits on politically motivated hiring and firing. But the mayor largely ignored the federal court decree. He could get away with it because he was above the law, in many respects. Daley I handpicked candidates for Cook County state's attorney and Illinois attorney general, says Bob Crawford, so he effectively controlled who got prosecuted and who didn't. And given his clout with presidents, who appoint U.S. attorneys, the mayor "made damn sure there would be no anti-corruption investigations by a wise-guy U.S. attorney he couldn't trust," Crawford claims.

Another potential source of scandal, giving public jobs to friends and family, was done almost openly in Daley I's time. Mike Royko called the administration a family employment agency. For instance, when Richard M. Daley was fresh out of law school (and having taken three tries to pass the bar exam), his father gave him the job as an assistant corporation counsel. Another son, Michael, became the attorney for the Democratic Party of Cook County, which Daley I controlled. Those who questioned the jobs he got for his sons—they could kiss his mistletoe, as the mayor famously put it in 1973, after news broke that he had secretly switched millions of dollars in city insurance business to a little-known Evanston firm that included his son John.

* * *

It seems almost laughable now, but when Daley II rode into office in 1989, he vowed to end corruption in city hall. Just weeks into his new administration, he told reporters that his office had found loads of dubious contracts by his predecessors that qualified as boondoggles. "There's enough of them to hold your nose," he said.

Yet contract cronyism has thrived under Daley II. Over the years, the city has routinely doled out millions in contracts to clout-heavy friends and associates of the mayor who are usually generous campaign contributors—the so-called pinstripe patronage. (A list of major scandals up to 2004 accompanies managing editor Shane Tritsch's Chicago story from July that year, "The Mystery of Mayor Daley." Go to chicagomag.com/daleymystery.) Nepotism, too, remains alive and well under the current administration. A 1999 Tribune investigation found that 68 relatives of the Daley clan had been on the public payroll at one time or another since Daley II took office.

With teeth now behind the Shakman decree, this administration has been tangled in charges of illegal patronage. Most notably, a federal investigation in 2005 uncovered "pervasive fraud" in city hall's hiring and promotions. Daley II's former patronage chief, Robert Sorich, a Bridgeporter whose father was the official photographer for Daley I, was convicted in 2006 of rigging city hiring tests and faking interviews to benefit Daley II loyalists. Three other city hall insiders were also convicted in the scheme.

Last year, Daley II finally settled the city's decades-long legal battle with the Shakman complainants. His administration agreed to end all political hiring (which officials repeatedly insisted never happens anyway) and create a $12-million fund to compensate victims of illegal political discrimination. More than 1,400 people have received payouts from the fund, according to city records.

Outright graft has also remained an issue for this administration. In one of the most notorious instances, the Sun-Times revealed in 2004 that Daley II's administration had given out lucrative trucking contracts to politically connected companies in exchange for bribes. In many cases the companies did no work—they just paid and got paid. The mayor's Bridgeport friend Michael Tadin led the pack of hired-truck contractors. After the story broke, Daley II announced that he wouldn't take campaign contributions from city contractors anymore (although he hasn't sworn off donations from contractors with the city's pension funds).

The latest black eye for Daley II came this past May, when seven building department employees and eight private developers were nabbed in a bribery scam in which the builders allegedly paid off city inspectors to falsify or expedite inspections. "We're talking systemic corruption," said David Hoffman, the city's inspector general.

Saying the charges were "appalling and regrettable," the mayor denied the notion that corruption was widespread in his administration. "You cannot condemn everybody for a few," he told reporters. "I don't know if it's systemic, but you can't indict everybody on that." Still, when U.S. attorney Patrick Fitzgerald announced the indictments, he noted, "There's every reason to think there will be more charges to come in the future."

* * *

The dynasty continues: Richard M. basking in his election victory in 1989

Related:

MAYOR DALEY'S BUCKET LIST »

Ten suggestions for how to use the remainder of his term

THE MYSTERY OF MAYOR DALEY »

Our special report

Mike Royko titled his 1971 biography of Richard J. Daley Boss, and the term perfectly fit the man and the times. When Chicago was still a lunchpail town, Daley I epitomized the hard-nosed, hard-driving chief of a gritty, rusting enterprise. Four decades later, in an era dominated by Wall Street, real estate, and the service economy, his son likes to describe himself as the CEO of the city, and that term also makes a nice fit, with its white-collar, corner-office connotations, its suggestion of efficiencies and eager MBAs.