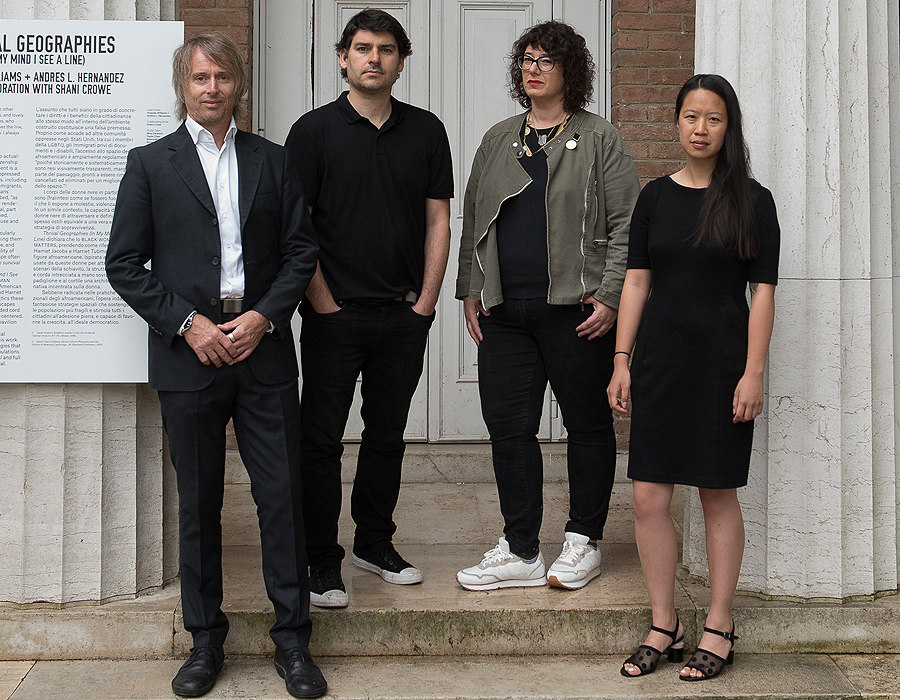

The U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale—a prestigious exhibition that brings together architects and artists around the world to examine the meaning of their practices—is well-represented by Chicagoans this year, as befits a great architectural city. Two of the co-creators are locals: architect Ann Lui of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Future Firm and art historian Niall Atkinson of the University of Chicago. (The third, Mimi Zeiger, is a Los Angeles-based critic and curator.) Iker Gil of MAS Studio is an associate curator; Studio Gang, artist/architect Amanda Williams, artist Shani Crowe, and SAIC's Andres Luis Hernandez all worked on installations at the pavilion.

We asked Kate Wagner, proprietor of the wonderful architecture blog McMansion Hell and a recent graduate of Johns Hopkins with a master's in Audio Science (where she focused on architectural acoustics) to talk with Ann Lui about the U.S. Pavilion and its theme, Dimensions of Citizenship. —Whet Moser

What are some of the skills and approaches that you’re bringing from your roles as an architect and teacher to your role as a curator?

I’d like to start off by telling you a little bit about the project, which I feel will help me answer the question. Dimensions of Citizenship and the US Pavilion I think is organized around two really broad and really big questions: First, what does it mean to be a citizen today? Second, what is the role of architecture specifically in researching, understanding and maybe starting to intervene in these questions of belonging?

I think that lately we’ve all noticed those urgent questions about citizenship both in the US and abroad, such as the discussion around Confederate statues, or Black Lives Matter taking to the street, or the question of what kind of spaces our bodies allow us to go into or not. Often the built environment is at the center at these questions, so I think it’s absolutely important that architecture specifically as a discipline start thinking and talking about issues of citizenship.

I think for me, being a designer and an architect, and in this moment, being a curator, it’s important for me to place an emphasis on the way architecture practices at the scale of the building but beyond the scale of the building; to be able to speak through a unique voice that questions of citizenships across a range of scales. That’s something, I’m really excited about what all our participants are doing.

I’m probably most excited about the work Jeanne Gang is doing with Confederate statues, being so close to the incident in Charlottesville, which of course sparked the teardown of these statues, and the way she’s relating place and material and space. What were you thinking when you brought her in?

I think Studio Gang’s project is incredibly exciting. They’re working in Memphis, Tennessee, and of course Memphis also had two Confederate statues which were actually on axis with the site they’re looking at, called Cobblestone Landing. So this is part of a broader project that Studio Gang is working on to create and use civic space at the Cobblestone Landing itself.

It’s a broad site, a really difficult site because of its association on the river, which was a site of a boom in the Memphis economy, it’s where they offloaded cotton bales and it’s where slave ships docked. So these cobblestones were rumored to have been used on ballasts on slave ships. So it’s a really difficult site, one for a city that’s reckoning with histories of inequality, segregation and slavery.

So Studio Gang’s project asks, “What is a specific monument that would be more inclusive for Memphis?” And that’s a really hard question, especially in the wake of the frustration and anger people had towards the Confederate monuments in that city and across the US.

The way they’re answering this question is through two strategies. One is to look very closely at the material of the cobblestone landing, to look at the incline of the hills, the stones themselves, to think about how the stones can be manipulated, designed, or transformed into inclusive space.

On the other hand, they’re doing a lot of really fantastic engagement with the citizens of Memphis. Part of the work for the Pavilion will be a film, with a range of nine citizen activists who have been making impact in the city at a range of scales, not just designers, but also advocates, community leaders, policy makers and talking with them and thinking with them about the kinds of communities they represent and advocate for and think about how this comes together in a work of architecture going forward for the future. I’m super excited about that.

Being that this is the US Pavilion, how do you see these projects fitting into a global context?

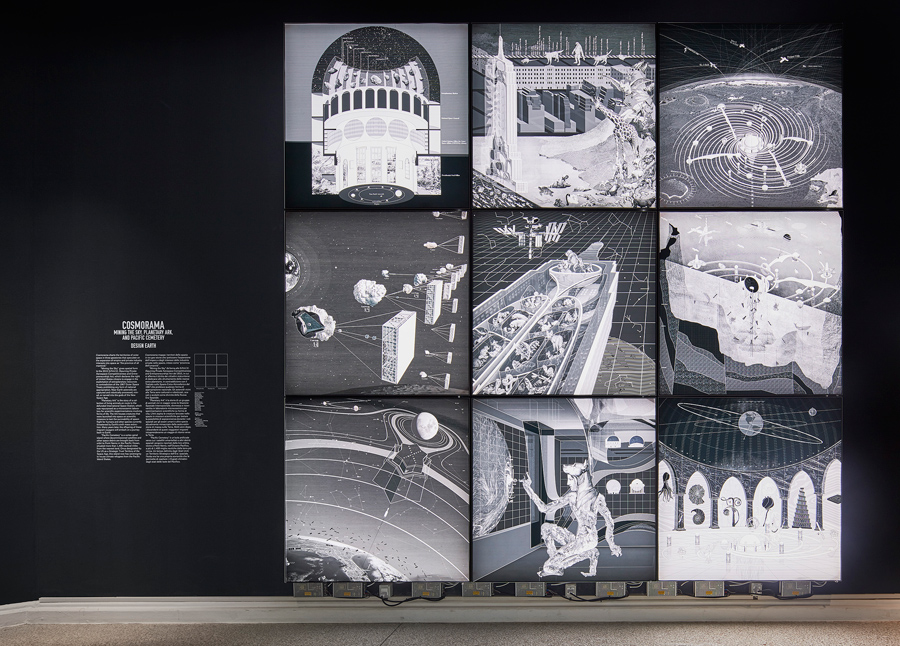

So we’ve organized the exhibition around seven scales, inspired by the themes of the Powers of Ten film: Citizen, Civitas, Region, Nation, Globe, Network, and Cosmos. So the idea is that each of the seven commissioned works responds to the idea of citizenship at a certain scale.

Nation is one of those scales, and we’re not trying to diminish both the violence and privilege of being associated with the nation-state, but kind of also pointing out that citizenship, whether that’s both belonging in terms of inclusion and exclusion, happens at a range of different scales.

You also belong to your neighborhood, or your voting district or you’re part of a watershed, or a part of a football team, or you’re part of a Facebook group for your high school graduating class. Or in the case of my family, you’re part of an immigrant diaspora. So there are different ways to become citizens at different scales of the built environment, and that’s something we’re asking our different participants to look at.

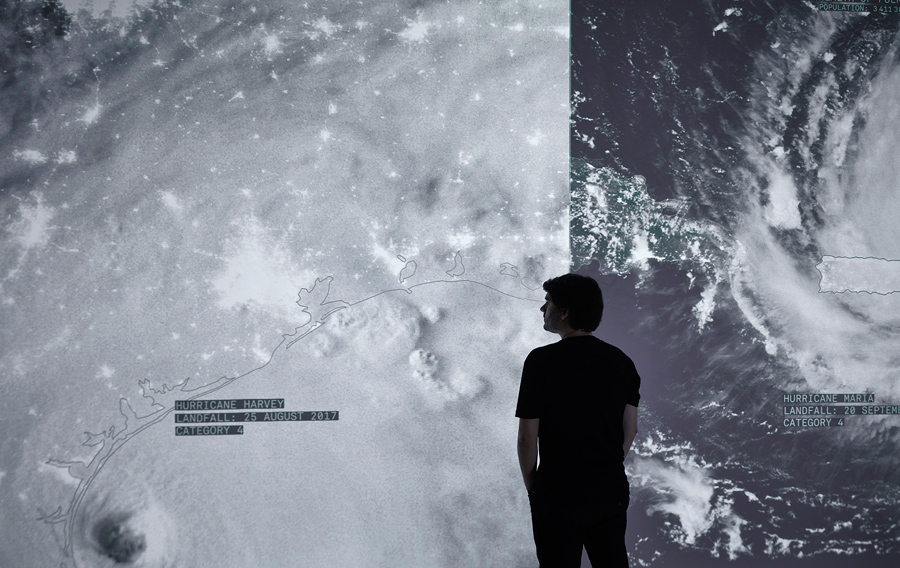

What I think that has emerged is that there are certain themes that span across these scales. So for example, at the scale of the nation, Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman are talking about the ecologies that span across the US-Mexico border and the ways that watersheds, as well as cultural, social, and economic ties across the US Mexico border. That’s something they have in parallel with Kate Orff at SCAPE, who’s also thinking about what it means to belong to part of a region that might face specific climate concerns or regional concerns based on ecology and environment.

So there’s a shorter answer to your question: we’re interested in representing US architectural practice, but our interest in citizenship is broad and goes beyond the scale of the nation and tries to encompass and look at these different modes of coming together.

You, as well as some of the participants and curators, are based in or somehow involved with Chicago. How do you see Chicago shaping the role of contemporary architecture, both in the Biennale and in general?

I feel like I should soapbox for Chicago, I love it. I’m based here, Iker Gil is based here, the two commissioning institutions are here, Amanda Williams, Andres Hernandez (working with Shani Crowe) are all Chicago-based, Studio Gang is as well.

I think Chicago is a city that faces a lot of problems, including segregation, including the fact that many of our neighborhoods are underserved and they have been brought up unequally. But it’s very clear that disciplines including architecture, planning, design, have been kind of complicit or have participated in creating the unequal landscape that Chicago is looking at today. So I think it’s important that architects and designers should reckon with this.

For example, Amanda Williams and Andres Hernandez are absolutely challenging that facet, both on the scale of the city and on the scale of race. On the other hand, I think Chicago is absolutely the kind of exciting place where people in both architecture, design, and art, are actually proposing transformative new ways of thinking about the built environment, and are approaching these bold questions from exciting new perspectives.

For example, Amanda, Andres, and Shani’s piece focuses around this idea that black women’s space matters, but they’re approaching it through the question of craft through Shani’s work with hair and braiding, and also through the lens of history; they’re inspired by the spatial practice of Harriet Jacobs and Harriet Tubman. So I think what’s important about Chicago is not to overlook the real problems the city faces, but also to point to the amazing people here who are starting to address those problems from a really unique perspective.

Can you talk a bit about Future Firm and its role in your design thinking?

So first of all, Future Firm is made up of myself and Craig Reschke, my partner. We always work as a team, and everything we do together. Our work has increasingly divided into on the one hand, territorial or installation experiments, and on the other hand what we call capital-A Architectural work. So across both these areas of our practice, we’re interested in the way architecture has agency in ecology, and politics, and economy.

For me, in general, my work has been about public space, whether public space exists or not, whether we can build it into spaces for discourse or arguments, who has the privilege and access to spaces designated as public in the city and who doesn’t. I’m trying to think through these questions both in our client-based work, which I think—despite capturing boring things like drywall sections or paving plans or looking at roof details—still always kind of speaks to and captures these questions of intersections between public and private and also through our more ad-hoc experimental work. You’ve been to a Night Gallery opening right?

Yes!

Night Gallery is our experimental, nocturnal exhibition space, and we’re really excited about doing more stuff at that scale.

This might be a dumb question, but what is it like working for the Biennale? It’s a huge deal, I mean, the state department is involved–what is the actual labor of the job like?

The State Department and the National Endowment for the Arts are involved on the government side, but I mean of course it’s a lot of work but we have an absolutely fantastic team. I’m going to name-drop my team a bit. We have a great curatorial team. I’m working with Mimi Zeiger and Niall Atkinson. And Mimi is someone I admired for a long time before I got a chance to work with her, who I think has over the past decade has developed an incredible and powerful voice in the discipline around questions of belonging but also the role of architecture in broader conversation.

Niall comes from a kind of history perspective, he’s been leading an aspect of the project, which reaches out into the city of Venice and expands the audience beyond the kind of crowd that comes to this kind of stuff, so that the local public is involved. Iker Gil is an associate curator on the project and Iker, you might know, runs this journal MAS Context which often does a public programming series that’s been a site of so many interesting and important conversations.

Our exhibiting teams are at a range of scales: Amanda is an independent artist, all the way to the scale of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, which works globally. There’s kind of these other satellite collateral components of the projects. There’s also a bit we’re calling the Transit Screening Lounge which is a presentation of five films mostly by artists not so much by architects or designers, and international artists which are amazing and exciting.

We’re doing a project called Form N-X00, which is 100 contributors internationally thinking and talking about citizenship. There’s a part of Form N-X00 which also mimics a way we’re thinking about the project, which is everyone we’ve asked, we’ve also asked them to bring a plus-one, to phone a friend. So that kind of project starts to include people that the curators might not have previously known about, it expands our boundaries of the project, outline of the discipline, outline of the geographic regions we might know better individually.

Our job is mostly to let these creators answer these big questions that we’re looking at, do their thing, and surprise us with the challenging and provocative work they’re doing. There’s one more name drop: we have this really fantastic designer on board, [IN-FO.CO] Project Projects, lead by Adam Michaels and Shannon Harvey. They are doing both the exhibition design, graphic design for the project overall, and the web design. They have been an amazing collaborator, challenging us, pushing back, but also organizing the framework about the exhibition that gives it a kind of legibility and coherence and it’s been an honor to work with them as well.

The topic of citizenship is timely, as US citizenship itself has become subjected to highly charged political rhetoric and practices, from T-shirts that say Build the Wall, to ICE raids separating children and families. These discussions will only get more heated with the increasing advance of climate change. It’s certainly powerful that citizenship was chosen as the topic of the US Pavilion.

I’m really glad to hear that. I think, that the exhibition of course can’t do it all, it’s not going to be encyclopedic, we’ve known that from the beginning. But what it does do is give a few really important case study and does really deep dives into those case studies.

For example, SCAPE, what they’re doing at the pavilion is using these ecological barriers which will then deployed at the site at Venice. It becomes this metaphor or framework for looking at cautions of wetland regions or coastal regions at risk around the globe. Or Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman looking very closely at this Tijuana watershed, which becomes a way to talk about all borders which become contested between nations.

What is exciting for me for me about it is that while we certainly don’t have to do it all, but maybe by asking some important questions, it starts to create a framework for ways to talk about these things that are important for us as citizens, and not just as designers, and to starts to give us a way or a space to work on these things in the future which is important for architecture to do.