As in many cities across the country, celebrations commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall rebellion are well underway in Chicago. One such show not to miss: About Face: Stonewall, Revolt, and New Queer Art, an ambitious exhibition of contemporary work by LGBTQ+ artists that opened Wednesday at Wrightwood 659 (659 W. Wrightwood Ave., Lincoln Park).

About Face spotlights how queer communities have empowered themselves in the decades since Stonewall, when, on June 28, 1969, a police raid at the eponymous New York City gay bar led to demonstrations largely credited with launching the modern gay and lesbian civil rights movement. This show examines that uprising's legacy through art, and explicitly through an expansive lens of queerness — what curator Jonathan David Katz defines as “this boundary-busting capability.

"It’s about trying to elevate the notion of trans-ness as the dominant metaphor post-Stonewall,” he says. “Transness in every regard — to questions of gender, but also sexuality and race. We can no longer speak about identity in singular terms.”

Spread across Wrightwood 659's four floors, the show serves as an example of mainstream institutions gradually embracing those who have long been outsiders. In terms of numbers, About Face is, according to Katz, the largest exhibition of queer art ever mounted, bringing together 492 works (mostly photographs and paintings) by international artists across the spectrums of gender and sexuality. The majority of them, notably, is neither male nor white.

You also won’t find a ton of household names here — no Warhols, no Mapplethorpes, no Goldins. That’s because Katz wanted to “cast a bright light on people who aren’t widely shown,” he says, whether in museums, in the United States, or simply at all.

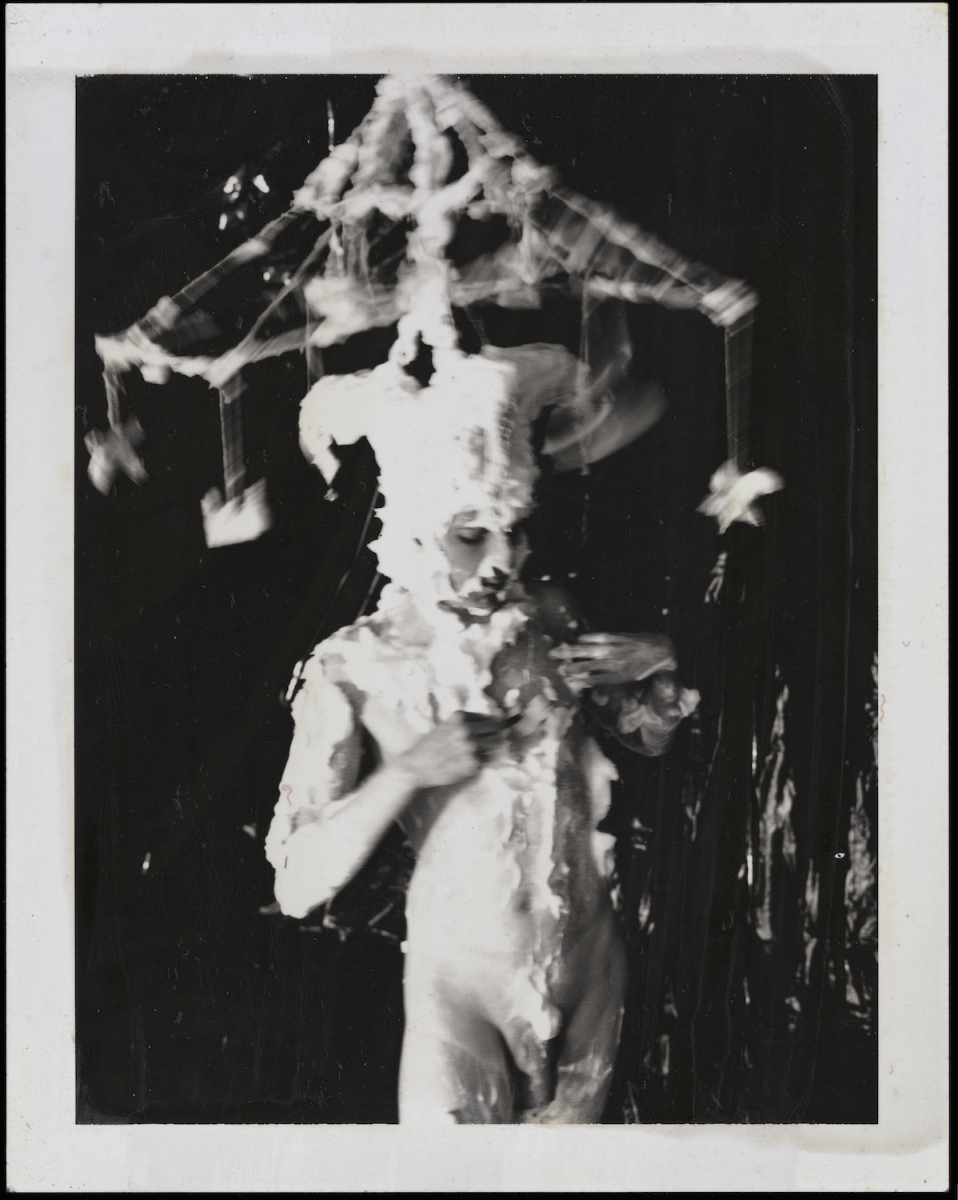

The result is an eye-opening — and even radical — showcase of intimate histories and narratives. There are portraits of sex workers in Baltimore by Amos Badertscher, a self-taught photographer who worked quietly and unceasingly for more than 60 years. There’s a devilish video by the 34-year-old Chinese artist Tianzhuo Chen (who has never before exhibited in America) that queers the Western art trope of languid bathers. There’s an astonishing series of never-before-seen photographs by Harvey Milk, the first openly gay elected official in California, who would have turned 89 on the exhibition’s opening day. Katz found the tender studies of Milk’s former lover, Joe Campbell, among his papers at the San Francisco Public Library. The photographs raise the question: What other forgotten treasures lie in the archives of artists who felt the world wasn't ready for their work?

Portraits fill the galleries of Wrightwood 659. Taken together, they evoke the sense that much of this art was created with a “by us, for us” mentality — because representation matters, and because these identities don’t often appear in the mainstream. Or because, when they do, they're often distorted, flattened, appropriated, whitewashed.

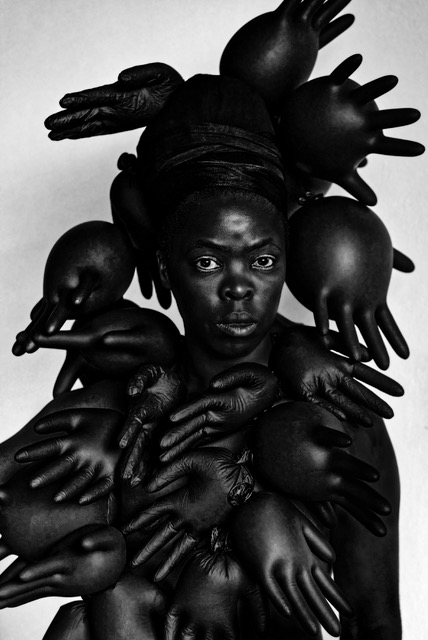

For instance, the South African artist Zanele Muholi, who uses the pronouns they and them, reclaims black identity through a series of dramatic self-portraits that construct their own definition of black beauty. Photographer Del LaGrace Volcano, who is intersex, unapologetically captures their multitude of selves in a series titled Gender Optional. In Blessed Avenue, an epic digital animation by the Brooklyn-based artist Jacolby Satterwhite, voguing avatars — one of them a self-portrait — play the protagonists in an Afrofuturistic vision of pleasure and freedom.

Elsewhere, there's work by the Indonesian-born photographer Leonard Suryajaya. One of the youngest artists in the show — and one of several based in Chicago — Suryajaya does not present himself in his images. Rather, he creates portraits of his relatives, painstakingly constructed to resemble stage sets. The photographs speak to Suryajaya's experiences of belonging and otherness. In some, Suryajaya's American partner leans against the artist's father or mother, his white body becoming an unexpected presence. The scenes reveal a vulnerability, but they assert: This is my family, with all its seeming contradictions.

Suryajaya recalls struggling to understand his sexuality before he moved to America about a decade ago, then struggling with being a queer person in Indonesia. About Face, he says, makes him feel “humbled” to see his work within this context of a queer America.

“As a queer immigrant artist, I think a lot about how I fit in with these trajectories — all these great people who worked their asses off to make sure I have the privilege I have today,” he says. “This show is groundbreaking for me because I feel validated.”