Three days before he died at the age of 93, James F. Short Jr. emailed me a paper with ideas and questions that had been swimming around his head for the better part of fifty years. What conditions gave rise to Chicago’s super gangs like the Gangster Disciples, the Black P. Stones, and the Vice Lords? And why was Chicago one of the few cities in the world where such gangs developed?

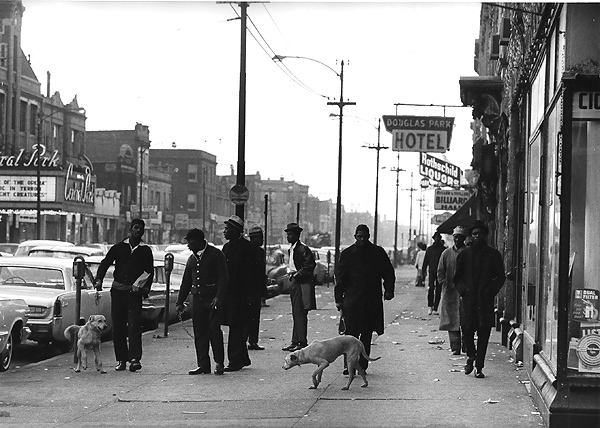

Chicago is a gangster city. The city’s gangs are the stuff of legend and shape Chicago’s image as a violent place. It should be of little surprise, then, that Chicago is also a city of gang research. Since the publication of Fredrick Thrasher’s 400+ page tome in 1929, The Gang: A Study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago, scholars, writers, and thinkers have turned to Chicago’s gangs and the neighborhoods they inhabit for insights into America’s “gang problem.” And Jim Short was a something of a legend in the world of gang research.

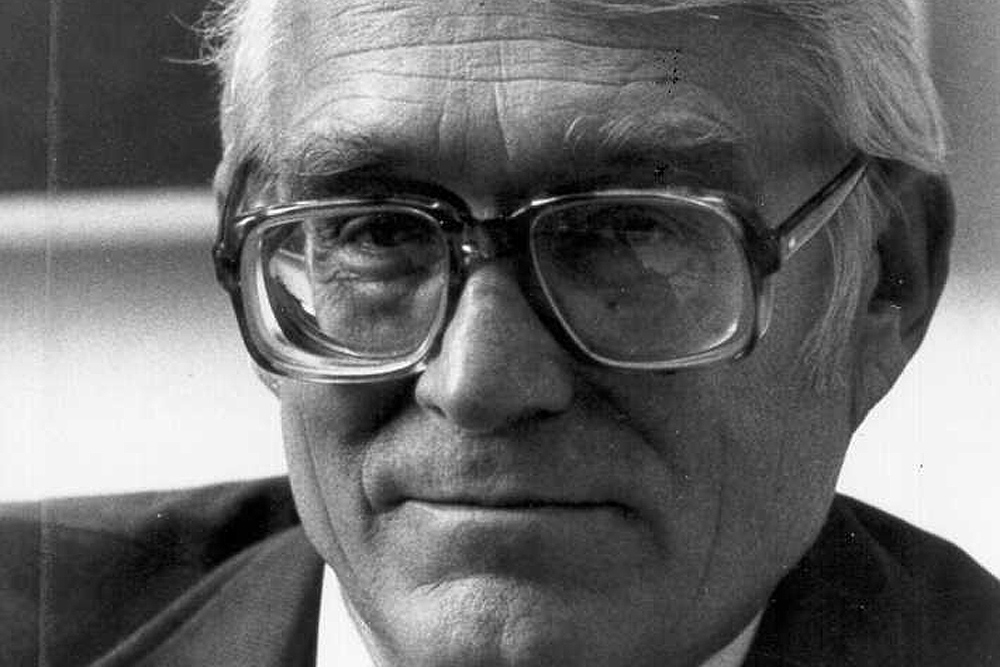

Jim’s name adorns a host of impressive things, including a statistical index used in criminology, a “best paper” award for urban sociologists, and an entire building on the campus of Washington State University. Jim served as the Director of Research on President Lyndon Johnson’s Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, a member of the Chicago Planning Commission, and as the President of both the American Sociological Association and the American Society of Criminology (the only person to have been elected to both positions). More than any accolade or award, what kept Jim motivated and writing well into his 90s was Chicago and its street gangs.

Born in 1922 in New Berlin, Illinois, Jim served as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Marine Corps Reserve in Japan at the end of World War II. His time in the military sparked his sociological imagination, and after graduating from Denison University in 1947, Jim pursued a Ph.D. in the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago.

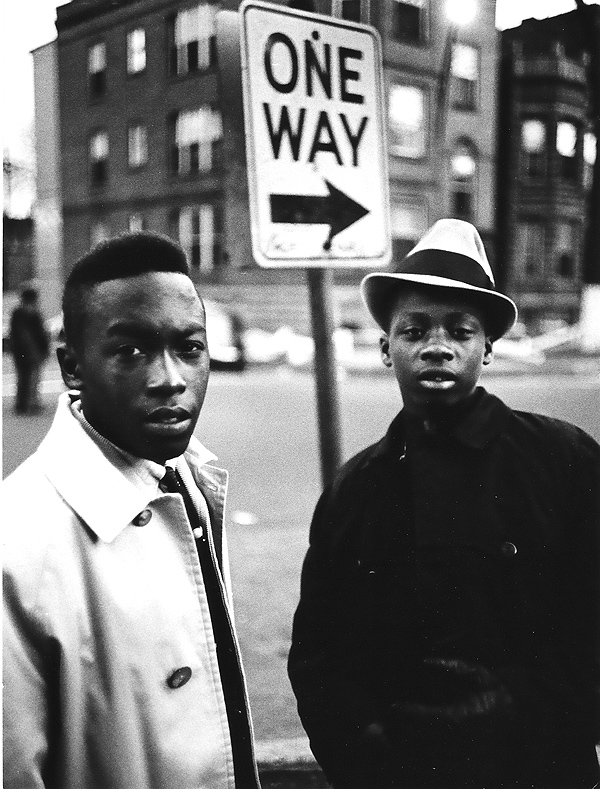

Between 1958 and 1962, Jim designed and implemented one of the most impressive studies of street gangs ever conducted. The Youth Studies Project (YSP) gathered data on more than 20 street gangs and 300 gang members, alongside 22 non-gang delinquent groups and 400 delinquent boys. These gangs and groups came from 10 community areas and they were intentionally selected to represent both white and black and lower and middle-class boys.

The YSP wasn’t some antiseptic bit of science divorced from the real world. The project was intimately tied to the YMCA’s Program for Detached Workers. Detached workers were some of the original violence interrupters in Chicago, who worked to get gang-involved young people into pro-social recreational, employment, and educational opportunities. These “curbstone counselors,” as they were sometimes called, came from the neighborhoods they served, many were veterans, most were athletically inclined, and one was an ex-convict. Like street-outreach workers of today from groups like Cure Violence, YMCA detached workers stood on corners solving problems and mediating disputes. The YSP worked hand-in-hand with the detached workers, debriefing and interviewing them bi-weekly about their activities and the on-goings of the gangs to which they were assigned.

The more than 15,000 pages of transcripts and detached worker reports produced by the YSP offer a window into the lives of young gang boys and their activities from the decidedly normal adolescent rituals of romance and pick-up baseball games to the more delinquent acts of “humbugs” (gang fights) and smoking “reefer.”

Jim’s research from the YSP was among the first to stress that gangs were first and foremost groups, not a collection of individuals with particular pathologies or misfit kids. The key to understanding and doing something about gangs, Jim would argue for decades, was to understand the underlying group processes at work and how they relate to individual and group behaviors. Threats to gang leaders or members, for example, can serve as a catalyst for mobilization to protect the status of the group—something as true today and perhaps even exacerbated in the Twitter era.

What kept Jim motivated and writing about Chicago gangs wasn’t so much what he had already learned from the YSP, but from what the YSP missed. The YSP halted data collection at exactly the same time as Chicago’s supergangs were coming into existence and just as some of Chicago’s infamous gangsters began building their gang nations. The names of the dozen or so white gangs in the YSP have long faded from our collective memory, as have the names of all of the black gangs except for one—The Vice Lords. Capturing just a hint of the early years of the Black Disciple Nation, a handful of YSP reports mention a “boy named Barksdale” affiliated with the Eastside Disciples. Had the YSP continued, the detached workers might have witnessed “King David” Barksdale, the charismatic founder of the found the Black Gangster Disciple Nation, giving interviews to the Wall Street Journal ("The Black Disciples," September 12, 1969) and helping run a nearly million-dollar grant from the Office of Economic Opportunity.

Chicago is an amazingly complex city. That the YSP failed to capture the rise of Chicago’s supergangs is a reminder that history is bigger than any of us. Yet, one of the key insights from Jim Short, and many of those who considered themselves a part of the “Chicago School of Sociology,” remains as true today as ever: context matters. One cannot understand something like gangs without understanding how they fit in time and space. The supergangs of the 1960s would not have emerged without the patterns of segregation and racism in the city nor without help and opposition from outside the gang itself. Jim spent a lifetime trying to piece together some of the insights Chicago’s gangs could offer social science and public policy. The last sentence of the paper he sent me on May 11th was a fragment, a thought a writer puts on page to serve as a later reminder: “More here?” Yes, Jim. There is still more here, more work to be done trying to understand the way Chicago and its gangs shape the way people live in this city. And, we are all better off because of the work you did and the questions you asked.