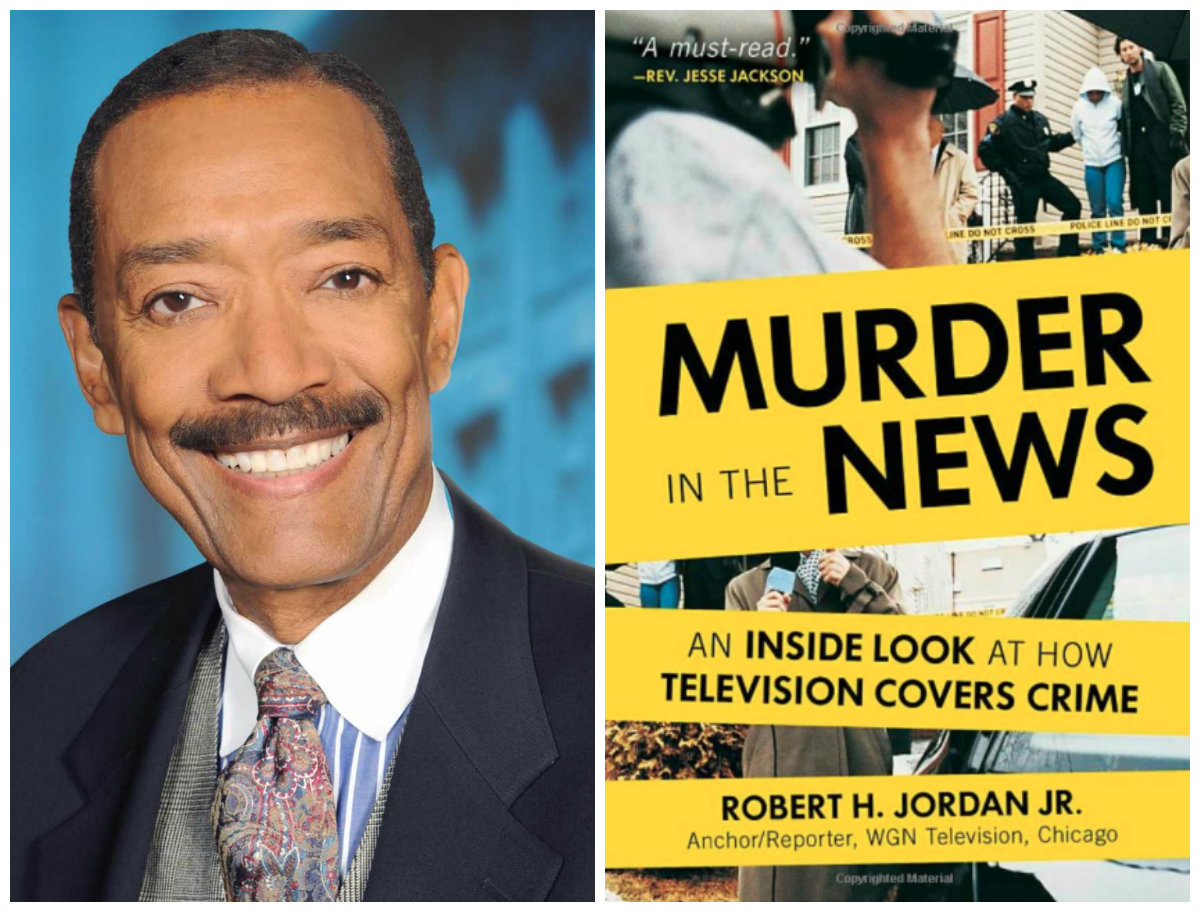

News veteran and retired WGN9 anchor Robert Jordan is laying out what he's learned from his nearly 50 years in the field. In his new book, Murder in the News: An Inside Look at How Television Covers Crime, Jordan explores how news stations decide which homicides to cover. The book goes step by step through television stations' newsgathering process when covering crime in a city.

Jordan talks with Chicago about the inspiration behind his new book and how crime has become a staple of TV news coverage.

Why did you feel it was important to write Murder in the News?

I think my goal was to help people understand how we make the sausage. The backstage operation is just as fascinating and interesting as what goes on in the field. The news is a collaborative process. From the assignment editor who gets the first phone call, to the reporter on the field, all the way up until it goes out the door.

It's important especially today when audiences are bombarded by these crazy proclamations of fake news, and the press is your enemy, and this sort of thing. Because in almost 50 years of reporting, I have never had anyone tell me how to write my stories. Ever. I’ve had discussions with editors on how I wrote my story. Maybe I didn’t have this fact clear enough, or I need to go back and check on some information, but I never had and have never heard of any cases where producers will try to tell reporters how to write a story.

Early in the book, you mention the Rodney King video and a woman scolding you for covering a scandal involving a congressman instead of the homicide of three African-American boys, which got you thinking about why certain topics are covered and others are not.

Yes. The Rodney King beating took place in ‘91, and the Congressman Mel Reynolds scandal happened around 1994. At this time, we were listening to public information officers from within the police department and taking what they said to be gospel. That’s how we did it at the time. After this woman said this shooting of three boys was more important than a sex incident involving a high-profile congressman, I remember thinking to myself: This is a good question. Producers and assignment editors could argue over that question in a newsroom meeting. Where do we send the crew? I wanted to look into that further, I never forgot it.

I decided to get a doctorate, and I looked at the audience as a basis for my dissertation. Later I decided to do more work with a questionnaire to the gatekeepers in our news industry —the assignment editors and our producers —and question them about their gut feelings about what is news.

What did you learn?

If you ask someone straight out: “Are all people the same? Should our news coverage of people be equal?" They’ll say, “Yeah, sure.” But that’s not the case. We, in our society, have an instinctive belief that some people are more important than others. Politicians, doctors, community leaders, people who have attained certain status —important. If they are murdered, then we give front-page, above-the-line coverage of that case.

If a homeless person or a minority is murdered, that may be ignored by the gatekeepers of our newsroom. Not because of any prejudice, but because of an instinctive belief that they are not as important to the audience as others are. They make this gut determination of what to cover in a split second.

Why has crime coverage become a staple in TV news?

In a way, murder is the perfect breaking news story. Every television station loves to have these huge banners, and agitated reporters and anchors saying: “We have a breaking news of a shooting that just took place.”

It’s important to capture audience early in the broadcast. The audience is so important for the bottom line. Consultants have told news directors in the city that having these breaking news banners is important to increase ratings.

If you have a murder, and you send out a crew to the neighborhood, you can stick the reporter in front of some yellow police tape. You can tape him or her in five minutes, make them stand there for a minute and a half and not say much. You don’t have to go and find the other side of that story. Murders are horrible and bad, and that’s agreed upon—unlike a story of a proposed tax increase, a school funding story, neighborhood issues over building a school playground here or there, where you really need both sides and different voices. That takes time; that’s an all-day story, it uses up your people.

TV stations have made crime the major ongoing diet. It’s easy, simple, and flashy. And you know it’s going to happen

When DNAinfo started, it tried to cover every homicide, knocking on doors to tell in-depth stories about victims. Do you think that coverage changed or influenced television coverage of crime in any way?

Well, I mentioned early in the book about asking our news director Jennifer Lyons that question. She said, "We can’t cover every murder. But it’s important that we realize that these victims are someone's child, and we need to compassionately look at them as not just as numbers, but as individuals."

I also interviewed Michael Lansu because he was doing the same thing for the Sun-Times before moving over to WBEZ. He was able to cover just about every murder that occurred. TV doesn’t. DNAinfo was doing a great job, calling the coroner's office, calling around, and even then some murders slip through the crack. Television stations cover a small percentage of the murders that occur, and there’s still filtering that goes on. And there’s some interesting filtering that goes on based on gut feelings of the assignment editors. If you take a black street gang member who is shot on the West Side, he may not get covered. Take that same kid and have some books under his arm walking to school as he is shot and killed, and we’d have helicopters in the sky.