Some of the Chicagoans whose names we use every day are Chicagoans we don’t remember at all. After all, how many of us know off the top of our heads how Daniel Elston, Andrew Dunning, or Mary Eliza McDowell made their fame? But they left their handles on local streets and landmarks that have endured long after their own notoriety expired. Here are just a few of the places associated with Chicago’s forgotten namesakes.

Wabansia Avenue

Opposing American expansion during the War of 1812, the Potawatomi chief Waubonsie fought against William Henry Harrison at the Battle of Tippecanoe alongside fellow chiefs Shabbona and Winamac, who also left their names to a park and a street here. During the attack on Fort Dearborn, however, he protected the family of John Kinzie (another street namesake) from the clash that took place during the evacuation. Waubonsie also refused to join Black Hawk’s 1832 uprising because he wanted to maintain good relations with the United States. Following Black Hawk’s defeat, Waubonsie sold the Potawatomi lands to the U.S. and moved west to Iowa, where the government built him a two-story log cabin. He still has a street on the Northwest Side, though.

Burnside

The Far South Side neighborhood is named for Civil War general (and inaugural NRA president) Ambrose Burnside, who is better known for an outlandish set of muttonchops that inspired the term “sideburns.”

Miltimore Avenue

Yes, there was a guy named Miltimore. This Northwest Side street is named for Ira Miltimore, City Council’s first abolitionist alderman. Miltimore was elected in 1844 with the support of the Liberty Party. The party’s view that slavery was in violation of the Constitution was, at the time, too radical even for moderate anti-slavery politicians such as Abraham Lincoln. Eventually, its members found their way into the Republican Party. Miltimore, who had left Chicago for Janesville, served as a captain in the 33rd Wisconsin Infantry during the Civil War. Miltimore also built the first permanent public school in Chicago, a structure so grand it was derided as “Miltimore’s Folly.”

Buckingham Place and Buckingham Fountain

The Lake View street and the fountain shown in the opening credits of Married… with Children were named after two different but related Buckinghams. The street was named after Ebenezer Buckingham, a banker who became wealthy owning grain elevators. The fountain was named after Ebenezer’s son, Clarence, who used his fortune to purchase works for the Art Institute of Chicago, which he served as a director. After his death, Clarence’s sister, Kate, donated $1 million to the park district for the construction of the Clarence F. Buckingham Memorial Fountain.

Fuller Park

This South Side neighborhood is named after Melville Fuller, a Chicago Democrat who served as Chief Justice of the United States from 1888 to 1910. Appointed by Grover Cleveland, Fuller voted along with the Supreme Court’s majority ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld Louisiana’s practice of separating black and white commuters into “equal, but separate” railroad cars. The separate-but-equal doctrine was overturned in principle by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, but Plessy v. Ferguson granted judicial blessing to Jim Crow laws until 1968. Consider Fuller Park on the growing shortlist of monuments, streets, and neighborhoods due for a name-change.

Shields Avenue

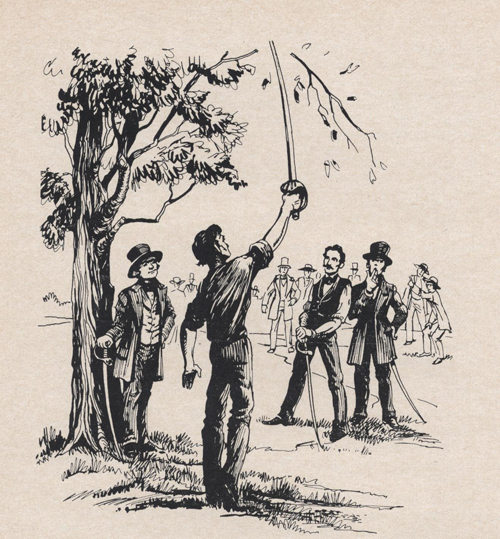

This street — made famous through its 35th Street intersection, where Comiskey Park stood — was named for James A. Shields, one of Abraham Lincoln’s early political rivals. When Shields was state auditor, state representative Lincoln wrote a snarky, anonymous editorial in the Sangamo Journal criticizing his decision to close the state bank. After learning the author’s identity, Shields challenged Lincoln to a duel. Lincoln accepted, and chose broadswords as weapons – an insuperable advantage, given that he was 6 feet 4 inches to Shields’s 5 feet 9 inches. When the two men met on Bloody Island, a sandbar in the Mississippi River belonging to neither Illinois nor Missouri, their friends persuaded them to settle their differences peacefully. Shields’s statue represents Illinois in the U.S. Capitol, and he is the only person to serve as senator from three states – Illinois, Missouri, and Minnesota.

Photo: The Astonishing Saber Duel of Abraham Lincoln by James E. Myers, illustrated by Betty Madden

Another James Shields pitched for the White Sox from 2016 to 2018. The fact that no one brought up this coincidence shows how much the original Shields has faded from memory.

Irving Park

Originally a suburb, Irving Park is named after the most famous Irving in American history. Not Kyrie, Washington — author of the short stories “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Its founders first named it Irvington, but changed it to Irving Park when they found out there was already an Irvington in Washington County, Illinois.

Willard Court

Along with James Shields, Frances Willard represents Illinois in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall. As the founder of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Willard was a household name in the late 19th century. In 1940, her face appeared on a five-cent stamp in the Famous Americans series. Alas, the great cause of Willard’s life, Prohibition, turned out to be a failure and her name faded from public memory.

Willard was also a leading suffragette, believing that, once empowered with the vote, women would use it to ban alcohol. Though she never got as much credit for the 19th Amendment as Susan B. Anthony, she’s commemorated by Northwestern University’s Willard Residential College and this West Town street.

Dunning

The name Dunning was once synonymous with insanity in Chicago, since the neighborhood was the location of the local asylum. Both in life and death, that facility was a source of misfortune for developer Andrew Dunning. After the Civil War, Dunning tried to start a village on what is now the Far Northwest Side. He had a hard time find people who wanted to live there, because the poorhouse and the tuberculosis sanitarium were nearby as well. However, his name became attached to the area when the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul railroad was extended to bring patients to the asylum — the so-called “crazy train” — and the county named the terminal station Dunning. For decades thereafter, parents told their misbehaving children, “I’m sending you to Dunning.”

The asylum was eventually acquired by the state and is now known as Chicago-Read Mental Health Center. Institutionalization has fallen out of favor as a mental health treatment, so today, the name Dunning is mostly associated with the quiet neighborhood near Harlem Irving Plaza.

Sauganash

Billy Caldwell was a half-British, half-Mohawk fur trader. Because of that background, he was known by this Potawatomi word meaning “English speaker” or “Englishman.” Caldwell fought for the British alongside Tecumseh in the War of 1812, witnessing the great chief’s death at the Battle of the Thames. After the war, he settled in Chicago, where he helped negotiate treaties between Native American tribes and the United States government, using his command of English and several indigenous languages. For his services, Caldwell was granted 1,600 acres along the Chicago River, on what is now the Northwest Side of the city. Caldwell’s name is still all over his old property: The neighborhood of Sauganash is named after him, and his baptized name is on Caldwell Woods, Caldwell Avenue, and the Billy Caldwell Golf Course.

McDowell Avenue

A protégé of both Frances Willard and Jane Addams, social worker Mary Eliza McDowell made her career in Back of the Yards, operating the University of Chicago Settlement House on what was then called Gross Avenue. It’s appropriate the street was renamed for McDowell, because she devoted her life to ensuring the original name no longer fit. When McDowell moved in, the neighborhood was littered with open garbage pits and oppressed by the stench of a stream nicknamed Bubbly Creek, which frothed and festered with offal dumped from the nearby Union Stockyards. For pestering City Hall to clean up the neighborhood, McDowell was nicknamed “Angel of the Stockyards” and “Garbage Lady,” and appointed to the first City Waste Commission in 1913.

Clybourn Avenue

Archibald Clybourn, one of Chicago’s original hustlers who helped establish our reputation as “hog butcher to the world,” spelled his name several different ways. When he arrived here, in 1823, it was Cliborne. He sometimes did business as Clybourne. The name on his gravestone in Rosehill Cemetery, and on the street that cuts a diagonal through the Northwest Side, is Clybourn. Clybourn built the first stockyard, which later became one of the city’s signature occupations, and had a contract to sell beef to Fort Dearborn.

It must have been a lucrative contract, because he also built a 20-room brick mansion on Elston Road (now Avenue), which is named after Daniel Elston, an alderman who lived there decades earlier. But the road long predates Elston, too: It was a Native American trail, as were Archer Avenue, Clark Street, North Michigan Avenue, Grand Avenue, and Vincennes Avenue.