I've never really had a specifically defined workday in my post-collegiate professional life: a specific time my work was expected to start, a requirement that I work basically no less or no more than eight hours, no additional pay if I did work more. And a lot of the stuff I do for "fun," like read about public policy, feeds into my work; conversely, a lot of the stuff I do at work is stuff I'd do anyway. But even with my slippery postmodern schedule, it's still broadly based around the concept of eight hours, almost 150 years after it was first fought for.

Much as the eight-hour day is associated with Chicago, labor's first real success in the eight-hour movement can be credited to Australia, thanks to a confluence of historical factors: its English heritage, from which the country inherited the Industrial Revolution-era labor movement, and the Gold Rush that brought the country wealth and gave labor leverage over capital:

The Tolpuddle Martyrs from rural Dorset in England were transported here in 1834 for a crime that says as much about the powers that sentenced them as it does about the workers. In the process of trying to form a union, the Tolpuddle men had been found guilty of the obscure offence of 'administering an illegal oath'. Robert Owen spoke at the first protest meeting held in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, saying that the working classes of Britain and Ireland were in a worse condition than any slaves at any period in history. William Cobbett claimed the agricultural workers of England had less freedom and greater hardship than the Negro slaves of America.

[snip]

The Tolpuddle Martyrs were freed by a royal pardon in 1836 and returned to England. Soon afterwards Australian workers began to organise themselves according to their crafts. Benefit societies were formed to cover workers when injured. They were the beginnings of Australia's trade union movement.

20 years later, Melbourne stonemasons led the fight for an eight-hour day, not long after the ten-hour day was adopted in England and France, and a decade before American workers began agitating for the same; that would, not coincidentally, have to wait for the end of the Civil War:

Perhaps the first nation-wide labor movement in the United States started in 1864, when workers began to agitate for an eight-hour day. This was, in their understanding, a natural outgrowth of the abolition of slavery; a limited work day allowed workers to spend more time with their families, to pursue education, and to enjoy leisure time. In other words, a shorter work day meant freedom. It was not for nothing that in 1866, workers celebrated the Fourth of July by singing “John Brown’s Body” with new lyrics demanding an eight-hour day.

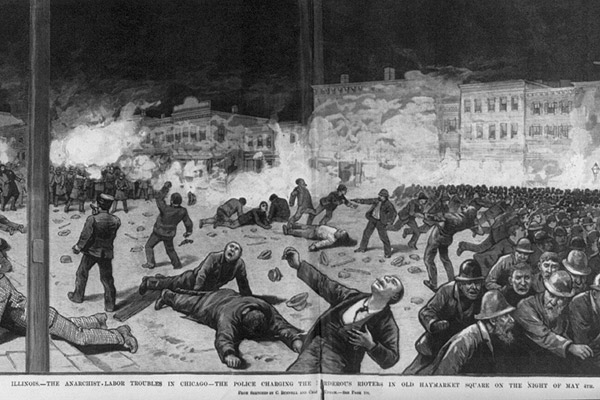

The most famous protest to come from the eight-hour-day movement was the Haymarket Affair, that crucible of the 19th century American labor movement, and one so often associated with May Day. But another, less famous but no less interesting, "riot" occurred two decades before that, when workers brought the city to a standstill by walking off their jobs en masse.

At the time, eight-hour-day laws were making the rounds: in Ohio, Wisconsin, Massachusetts, among others. As April 1867 came to a close, the Illinois legislature was prepared to pass its own, but it was full of holes, being implemented only "where no special contract exists." Employers rushed to institute special contracts. Employees of the McCormick reaper factory, according to the proprietors, "agreed to work eight hours, calling that a legal day's work," but were "willing to work two hours more, calling that 'extra hours.'" The railroads were uniform in working around the new law:

"On and after May 1, 1867, all employees of this company [the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad Company], in the State of Illinois and Wisconsin, not employed by the year or month, or by special contracts, will be engaged and paid by the hour, at a rate equal to one-tenth of the rate per day heretofore paid, until further notice. The same number of hours of labor will be required, and the same rules and regulations will be observed as heretofore."

Most companies threatened to close altogether or to fire all employees unwilling to work ten-hour shifts. The one exception the Tribune found were stonecutters: "The Stonecutters have been working on the eight-hour system since the first of March and it appears to be quite satisfactory on both sides. They began with three dollars and a half per day, and they are now receiving four dollars a day." Four dollars a day in 1867 is about the equivalent of $60 a day today, or about minimum wage for an eight-hour day in Chicago, for what then was one of the better-paid, higher-skilled laborer's positions.

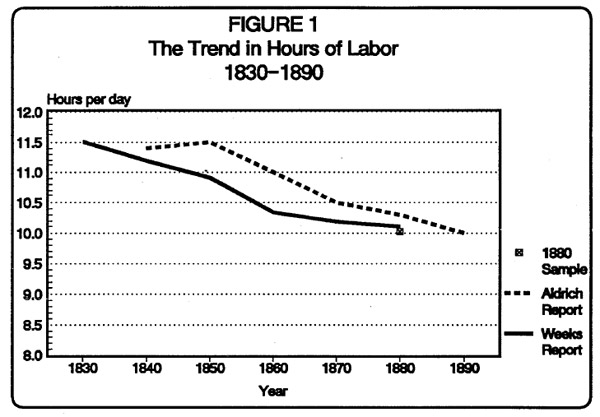

But the day for the majority of Chicago industry laborers was probably longer than ten hours, if it was anything like the typical industry day as illuminated by historical research:

(It's likely that one victory of labor agitation over the workday was a mere awareness of how many hours it entailed. Jeremy Atack and Fred Bateman, writing for the NBER, note that before 1880 the historical record on the subject is poor, but the record starts to improve beginning in in the 1870s, as Massachusetts and Ohio began recording work hours in their annual Bureau of Labor Statistics reports. National data begins to show up in 1886. This can't be dismissed—even though the actual accomplishments by the labor movement in shortening the work day were brief and unstable during the 19th century, defining it as an important metric was part of that process.)

On May 1, an estimated five thousand men marched in celebration: "it would be scarcely true to say that a majority of [workingmen] joined in the demonstration. The procession was certainly a large one, but it did not include more than a one-third minority of the workingmen of Chicago."

The next day? "EIGHT HOUR RIOTS – The Day After the Celebration – General Suspension of Labor—Violence in the Workshops – Mob Law Instituted – Gangs of Rioters Visit the Manufactories and Yards and Drive Men from Their Work – Bridgeport and the West Division in the Hands of the Malcontents – Meeting of Employers—No Concessions to be Made to the Mob. – A Day of Excitement and Tumult."

But they weren't riots, not exactly:

Yesterday was in some respects the age of a short-lived reign of terror. It was not of that bloody character which has marked some revolutions in the old world, or riots in other cities on the continent. But the controlling spirit was equally reprehensible…. It was an effort to prevent men from selling their own property (their labor) on such terms as were agreeable to both seller and purchaser. It was the voice of the slave power crying out—"You shall work only when, where, and on such terms as we dictate."

I mean, what sort of terror would you expect from a bunch of lazy people?

One other element was noticeable in the crowd of rioters—the presence of a great many men who are not acknowledge having any legally recognized means of subsistence: men of the genus "loafer," who are usually to be met with lolling round street corners or waiting, Micawber fashion, for anything suitable to turn up…. It is perhaps not the fault of about a tithe of these men that they have no work to do…. A great majority of them, however, neither work nor want to work; they are ready for any [illegible] which offers the chance of making money, be it by knocking a man down in the street or breaking into a house at midnight. These men were the real leaders of the mob of boys yesterday. They were not men who have been working ten hours per day and paid for that number of hours, but men who have no desire to work at all.

A central problem with the U.S. economy, [former Bain Capital managing director Edward Conard] told me, is finding a way to get more people to look for solutions despite these terrible odds of success. Conard’s solution is simple. Society benefits if the successful risk takers get a lot of money. For proof, he looks to the market. At a nearby table we saw three young people with plaid shirts and floppy hair. For all we know, they may have been plotting the next generation’s Twitter, but Conard felt sure they were merely lounging on the sidelines. “What are they doing, sitting here, having a coffee at 2:30?” he asked. “I’m sure those guys are college-educated.” Conard, who occasionally flashed a mean streak during our talks, started calling the group “art-history majors,” his derisive term for pretty much anyone who was lucky enough to be born with the talent and opportunity to join the risk-taking, innovation-hunting mechanism but who chose instead a less competitive life. In Conard’s mind, this includes, surprisingly, people like lawyers, who opt for stable professions that don’t maximize their wealth-creating potential.

Anyway, these layabouts managed to basically shut down the city's economy, as the Tribune ran updates of which businesses remained open. Caulkers were on the eight-hour day, and "represent themselves as well satisfied with the new arrangement." The Northwestern Iron Manufactury was "closed for the purpose of taking account of stock." The Eagle works of P.W. Gates closed because "business is dull and repairs are needed."

The general strike lasted for the better part of a week. On May 7th, the Tribune reported that work had "generally resumed," and that "there is every prospect that the city will be speedily restored to a state of tranquility," after the loafers had ceased causing trouble. On the whole, the ten-hour employers could claim victory, as a survey of businesses on West Division found, but some acquiesed to the vague new law: at the Northwestern Horse Shoe Nail Manufactory, Reisig's Boiler Works, and Murray Nelson's elevator the men got eight hours' pay for eight hours work; in Flood's trunk shop, they got nine hours of pay for eight of work. Most others stayed on the ten-hour plan. Despite the commotion, it was ultimately a defeat:

After several days of the strike, the state militia arrived and occupied working-class neighborhoods. By May 8, employers and the state they controlled had won, and workers went back to work with their long hours. The loss of the eight-hour-day movement led also to a massive decline in unions, and the labor movement would not pick up in such numbers for almost two decades.

In this sense, the Haymarket Affair was a skirmish, not the first, and not the last, in the very long movement toward the eight-hour day, and not even the first May Day to come from it. The institution of the eight-hour day would require another political confluence, eighty years after Australia's: FDR and the reconstruction of the American economy after the Great Depression. And with unemployment high and productivity up, it's at the center of the working world again.

Illustration: Library of Congress