The Heartland Café, the 42-year-old Rogers Park restaurant that recently announced it will close at the end of the month, was one of the places Barack Obama debuted as the Barack Obama who would become President of the United States.

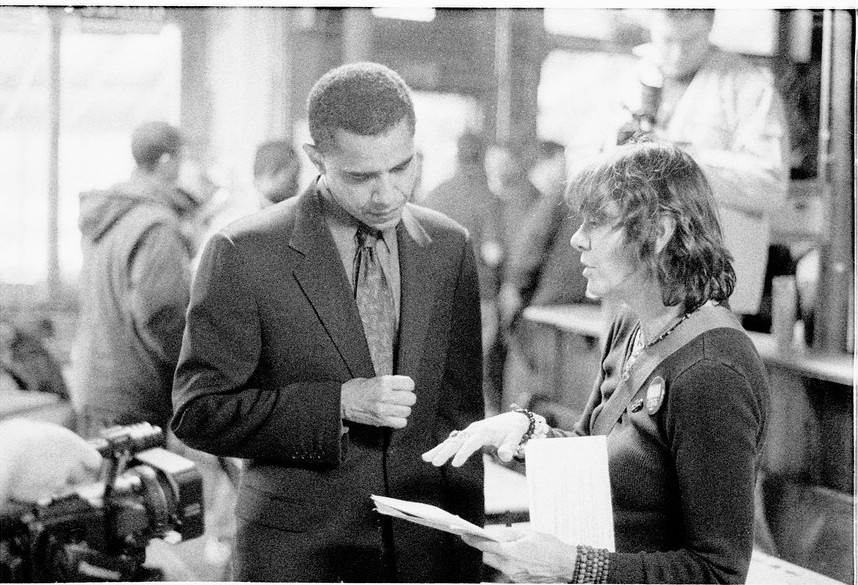

Obama spoke at the Heartland in the winter of 2004, when he was running for U.S. Senate. During that primary cycle, there was no better place to watch him work his base than Rogers Park. In the crowded dining room, the 42-year-old rubbed elbows punk rockers, old hippies, West Indian immigrants, adjusting his language as he moved through the room in the same way he would for a speech at a Southern Illinois farm cooperative or a Chicago Baptist church. The local ward organization had expected 100 people. More than 300 showed up — so many that latecomers were turned away.

Obama was introduced by the local alderman, Joe Moore, who, like Obama, had spoken out against the Iraq War in 2002, appearing on the Today Show to argue for diplomacy.

“I was here some 21 years ago, almost to the date," said Moore, "the last time this room was as filled as it is today, and that was for Harold Washington. “He had this room filled with the same kind of energy that is here today.”

I was at the Heartland that morning. I hadn’t heard Obama speak since 2000, when he was running for Congress against Bobby Rush. In that first speech, he addressed the meager crowd in the pedantic cadences of a University of Chicago law lecturer. That's one reason he lost so badly: In 2000, the first black president of the Harvard Law Review had been a passionless resume in search of an office.

In the intervening years, though, Obama had worked on his delivery, studying preachers on the South Side. As soon as he opened his mouth at the Heartland, he lit up that little room. This Obama believed in something, and he was able to make everyone else believe in it, too:

“A lot of people ask me, ‘Why would you want to go into politics?’ Even in this room that is full of activists, there is a certain gnawing cynicism about the political process. We have a sense that too many of our leaders are long on rhetoric, but short on substance

[snip]

What I suggest to you today is what I told people when I first ran: that there is another tradition of politics, and that tradition says that we are all connected. If there is a child on the South Side of Chicago that cannot read, it makes a difference in my life even if it’s not my child. If there is a senior citizen in Downstate Illinois that cannot buy their prescription drugs, or is having to choose between medicine or paying the rent, that makes my life poorer, even if it’s not my grandparent. If there is an Arab-American family that is being rounded up by John Ashcroft without benefit of an attorney or due process, that threatens my civil liberties, even if I’m not Arab-American.

[snip]

The reason we can share this space is because we have a sense of mutual regard, and that’s the basis for this country. E Pluribus Unum. Out of many, one.”

The Heartland crowd was hearing an early version of the speech that would make Obama famous. Later that year, at the Democratic National Convention in Boston, I heard the same rhetoric, and felt the same energy, that he had projected across that small room inside the Heartland.

David Axelrod, Obama's campaign manager, would later say of the Heartland speech: “When I felt the enthusiasm in that room, that was when I felt the tide had turned for Obama.”

Plenty of other restaurants offered better food and service than the Heartland. The healthy-to-a-fault meals required real effort to chew. The spaced-out waitstaff took a geologic age to write down your order, and another to serve it. Heartland's old hippie founders once resorted to holding fundraisers and selling memberships to cover $118,000 in bank overdrafts. On another occasion, the kitchen was shut down for sanitary violations after a customer contracted food poisoning.

And yet, the Heartland stayed open far longer than more professionally run establishments. It was a beloved community institution. It reflected Rogers Park’s image of itself as a community of eccentrics, misfits, and free spirits hiding up there in the attic of Chicago.

The restaurant's founder, Michael James, remained dedicated to the counterculture causes of his 1960s youth, inviting activists onto a Saturday morning radio program, “Live from the Heartland,” and serving as president of the 49th Ward Democratic Party.

You could find all the lefty rags on the magazine rack: not just The Nation, but fringe titles like Dissent, Adbusters, and Z. The restaurant even had its own magazine, Heartland Journal, filled with essays, poetry, and political commentary. A Heartland meal came with a free side of do-gooder cred.

Needless to say, I ate there all the time, and always brought visitors from out of the neighborhood. (The Heartland was never a “vegetarian restaurant,” it just served tofu scrambles before anyone else. Buffalo burgers were also a specialty.) I also competed in 5K races put on by Heartland Athletes United for Peace. (There was no starting gun. James just shouted “Go!”)

James and his co-founder, Katy Hogan, sold the Heartland in 2012. The new owner ran it like a business, streamlining the menu and replacing part of the dining area with an organic food market. It was never as charming after that.

Now, the owner is working to sell the outdated, century-old building because, he told the Tribune, it’s too expensive to maintain as a restaurant. The Heartland may move to a new location, but it would be the Heartland in name only.

Whatever happens, the Heartland Café will always occupy a place in Chicago history. It was the perfect venue for Obama to rehearse the magic that would later spellbind a nation.