It’s 5:30 on a sweaty June afternoon. the Hawk swoops beak-first through the back halls of U.S. Cellular Field, where the Chicago White Sox are off to their best start in years. A little bit Johnny Cash, a little bit Leisure World with his silver hair and black polo shirt over black slacks, he rides the air-conditioned thermals like a bird of prey—if the bird were a Boca retiree on a fierce mall walk. His cream Izod loafers flap across the plush pile carpet as he wings his way toward his broadcast perch high above home plate. There he will alight and—as he has done for nearly three decades and some 6,000 broadcasts—spend the next three and a half hours cawing out the play-by-play for the 100,000 or so fans who typically tune in.

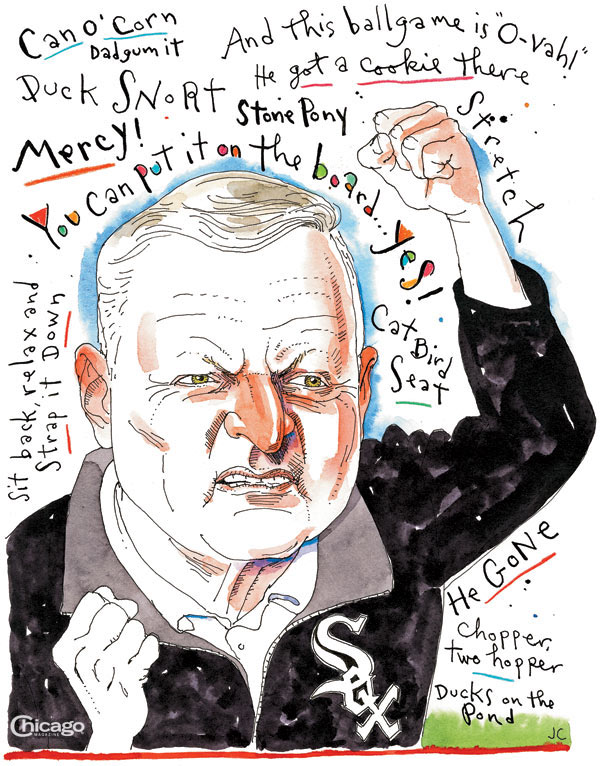

In a nasal South Carolina twang thick enough to pour on pancakes, he ladles out what to some is the broadcast equivalent of comfort food, dipped up from his bird feed sack full of stock phrases: “Can o’ corn!” “Duck snort!” “He gone!” “Mercy!” He makes others want to put on cowboy boots and kick in the television screen. Such is the power, the glory, and the preternatural gift to irk of Ken “Hawk” Harrelson, who turns 71 this month, the most wildly polarizing and arguably the most reviled sports broadcaster in Chicago (at least on the North Side) and, perhaps, in the country.

Consider: GQ magazine named Harrelson and partner Steve Stone the worst announcer team in all of baseball in 2010. And in February, FanGraphs, a website devoted to baseball statistics and analysis, also ranked the duo dead last. Both sources made it clear that the abysmal showing wasn’t the fault of Stone.

To his supporters, Hawk is an original: a folksy, funny, salty character in a flavorless porridge of broadcasting blandness. “He’s a beauty,” says longtime Chicago Tribune sports columnist Bob Verdi. “He’s entertaining. He’s show biz. Of course, if you’re a Cubs fan and you’re watching him, your blood’s probably boiling. But I don’t think Hawk cares about that.”

To his detractors—and they are legion—he’s an insufferable, cliché-spewing caricature: Harry Caray, minus the cuddly. He is prickly, petulant, and apt to go off on silly rambles, they say, chattering about glory-days esoterica, such as the best player he’s ever seen at breaking up a double play to extend an inning (Carlton Fisk).

Mostly, critics rip him for his “homerism”: his blatant, in-your-face rah-rahing for the “good guys”—always and only the White Sox. But it’s the accompanying operatic rants against umpires (who make boneheaded calls against “us”), along with bitter dustups against a handful of people close to the game, that have ruffled the most feathers.

There was the Joe West meltdown of 2010, in which Harrelson repeatedly called the home plate umpire a “joke” and a “disgrace to the umpiring profession.” There was his ugly feud with former Sun-Times columnist Jay Mariotti—a deeply controversial figure in his own right after several brushes with the law—with whom Hawk almost came to blows in a press box in 2004. Most often, such kerfuffles were met with amused chuckles, a segment or two of chat on the local sports talk shows, and maybe a brief dressing-down by Jerry Reinsdorf, the owner of the White Sox.

But earlier this season, the Hawkeroo (as he is known by both friends and foes) flew a little too close to the sun even for him. A rant against umpire Mark Wegner during a May 30 game against the Tampa Bay Rays, which became an instant YouTube classic, sparked debate among fans and the sports commentariat about when enough is enough. Wegner tossed out White Sox pitcher Jose Quintana for allegedly throwing at a batter, and Harrelson launched into a Hawkian harangue for the ages.

“What are you doing, Wegner?” he screamed, his voice quivering with rage. “You gotta be bleepin’ me. What in the hell are you doing? . . . Here’s an umpire in the American League that knows nothing about the game of baseball!” Harrelson not only criticized Wegner but called for his suspension.

In the aftermath, tail feathers tucked, Hawk had to explain himself to Reinsdorf—the explanation taking the form of an abject apology. He was also called to account by the commissioner of baseball, an almost unprecedented occurrence for a broadcaster. Even then, while sorry for the outburst, Hawk couldn’t promise it wouldn’t happen again.

For years there have been calls for Hawk to go. Tune in to any sports radio show, read the comment boxes on any online story about him, and for every passionate defense (“Love Hawk and I dread the day when he won’t be the voice of the Sox,” posted one commenter on the blog South Side Sox), there’s an equally passionate denunciation (“The fans of Chicago absolutely deserve better than this. There is no way I could ever endure a full season of listening to his bullshit,” a reader posted on Heave the Hawk, a site popular among Harrelson critics).

Yet Harrelson has won five Emmys and, two years ago, the Ring Lardner Award for excellence in sports journalism. The latter honor puts him in the company of such deeply respected broadcasters as Ernie Harwell, Bob Costas, Greg Gumbel, and Brent Musburger. After everything, and seemingly against all odds, not only has Hawk hung on—he’s soared. The obvious question is how.

* * *

Illustration: Joe Ciardiello

Harrelson at work in 2012

It’s a perfect night for baseball. Harrelson, heading to his booth, fist-bumps a security guard, a commissary cashier, a couple of suits shooting the breeze in the hall—all of whom smile and say things like, “Go get ’em, Hawk!”

He rounds a corner and passes a plaque featuring a silver image of him and an inscription that declares the entire floor and its warren of media suites to be the Hawk Harrelson Broadcast Level. That honor was bestowed on him before the beginning of last season, a couple of months after he inked a new four-year deal to call White Sox games that virtually guarantees he will be around to celebrate a full 30 years as the TV voice of the team. A grin here, a little wave there, and Harrelson lands at last in his own personal catbird seat: a black swivel office chair pulled up against a ledge in a small glassed-in split-level booth a few rows above home plate.

At 6:35 the windows swing out, and with a whoosh, the muggy hot-dog-and-beer-fragrant breeze chases the air-conditioned chill into the warm summer evening. Hawk, his great head already bent to his scorecard, doesn’t dwell on the beauty of the diamond spread out before him: the perfect grass, the pinwheel scoreboard, the green seats filling with early arrivals. Plenty of time for that over the next three hours.

Instead, as he prepares, his eyes dart back and forth—alternating between notebooks and a flat screen with an in-progress game between the St. Louis Cardinals and one of the Sox’s division rivals, the Detroit Tigers. “That’s a good matchup,” Harrelson says to Stone, who looks up from his own preparations at the dueling pitchers and nods at the screen. “Yeah, I think Verlander’s going to be psyched for this one.”

The pair has been together since 2009, when Stone took over for Darrin Jackson, who now calls Sox games on the radio for WSCR-AM 670. Whispers to the contrary, Harrelson insists that he’s gotten along with all of his partners, including Jackson, who popped Harrelson with a verbal jab during one of their early broadcasts. “You need to change that cliché,” Jackson said, to the delight of Harrelson haters everywhere. “ ‘Can of corn’ is getting old.”

“Well, why don’t you think of something yourself,” Harrelson snapped.

The exchange hung in the air for several seconds; for the next few days, it lit up the lines at sports talk shows.

To this day, Jackson insists he was just ribbing Harrelson, who agrees the whole thing was overblown. And indeed, earlier on this night, when the two bumped into each other, they exchanged what seemed to be genuinely friendly words. “One of the sweetest guys you’ll ever want to meet,” Harrelson says about Jackson.

Harrelson and Stone are cordial and professional but say little between innings and almost never look at each other. Stone—who has a long and distinguished resumé, including working with legendary Cubs announcer Harry Caray—has seemed to many the perfect foil for Harrelson. His knowledge of the game and his personality are equally strong; he can stand up to the occasionally withering challenges of the Hawk.

“He knows baseball backward and forward,” Stone says. “He does get a little aggravated sometimes. When the team is winning and things are the way they should be, it can be a delightful broadcast. When the team is losing, he’s not really too happy about that, and then the broadcast is a little different. That’s just kind of the way it is in Hawkville.”

As the first pitch from Jake Peavy (“the Jakemeister,” in Hawkese) sizzles over the plate, I settle in for the broadcast. I begin by listening for Hawkisms and marking them down in my notebook. It doesn’t take long. At 7:11 comes the first strikeout and the first “He gone!” At the end of the inning, it’s “Their guys nothing, our guys coming to bat.” Over the next couple of innings, they come in bunches: “Now he’s got the catbird seat.” “Ducks on the pond.” “High and deep! Stretch!”

They come so fast and so often, I eventually stop writing and simply enjoy the show, his juggling act of recording each out, squeezing in promos, bantering with Stone (“Stone Pony”), turning a baseball over and over in his hand during the innings.

And of course, surreptitiously, I study the feature that quite literally defines him: the Nose. Wide, curving, webbed with the faintest filigree of capillaries, it juts from the middle of his face like Mussolini’s chin: defiant, fierce, indomitable. Forged from five breaks—one from an accidental baseball bat to the face when he was seven, two from football injuries, two from fists—it is his Samson’s hair, his Spidey web, his Excalibur.

“My nose is directly responsible for my name,” Harrelson wrote in his 1969 memoir, Hawk. “Indirectly, it’s responsible for just about everything else about me—my clothes, my hair, my shoes, my car, my apartment, my refusal to follow the crowd, my independence, my complete departure from convention. If I had an ordinary nose, I’d be an ordinary guy—regular enough, I suppose, but nobody you’d look at twice. But with my nose, I had to be different, if for no other reason than to divert attention from it.”

* * *

Photograph: Nam Y. Huh/AP/Corbis

Harrelson in 1968, taking a swing

Born in the mill town of Woodruff, South Carolina, and raised in Savannah, Georgia, Harrelson was deeply affected by his parents’ divorce. “The last thing I remember about [my father] was hitting him,” Harrelson says. “He and my mom got into an argument and he hit her. And I went over and hit him as hard as I could. Of course, an eight-year-old isn’t going to do anything with an adult, but he stopped and he just looked at me.” Harrelson’s breath catches for a moment. “He walked out the door, and I didn’t see him again until I was in the big leagues.”

His mother, Jessie, a secretary at a meat plant, earned only $56 a week. “There was a financial drain, but the most devastating part was the emotional drain,” Harrelson recalled in a 1986 interview with Chicago. “I’d watch her go over her checkbook and she’d just break down and cry.”

He badly wanted to help. Sports provided the means. Harrelson was a star athlete in nearly every sport growing up, including football and basketball. (When he took up golf at 17, he was shooting in the 90s within three months of his first round; he shot par after six months.) Baseball, the career he would eventually choose, was actually his worst sport, but because it was the one his mother preferred, it’s the one he pursued hardest.

Boosters from Harrelson’s high school, desperate to keep him playing ball there, paid him $40 a week to paint tanks at the local gas company. Later, he says, he added to family coffers—and bought himself drinks—by hustling pool.

One of his favorite stories is of the time he was in a basketball tournament and was waiting for his mother to arrive at a game. To get there, she had to drive more than 200 miles after work, but she had never failed him yet. As tip-off approached, however, she had not appeared. “Everybody knew how close my mom and me were,” he says. “And when she wasn’t there, I said I wasn’t going to play. Well, she used to wear a red wool suit to the games—we called it our lucky red suit—and two to three minutes before the tip-off, I look up, and there she is on the top row, shouting, ‘I’m here, son! I’m here!’ ” The next day a columnist wrote about the “mysterious lady in red” and how she saved the game.

“I remember one time we walked into the gym at the biggest school in the state,” Harrelson continues with a laugh, “and they had a picture of a 40-foot nose along one side of the gym, with the words ‘Mama’s Boy’ in smaller letters. I was proud of it.”

That moniker was much easier to take than taunts about his nose: Banana Nose, Hooknose, Schnoz, Eagle Beak. It wasn’t until he was 17 that the nickname Hawk landed and stuck. Ribbing Harrelson over a hitting slump, his minor-league teammate Dick Howser joked that he looked a little like the cartoon character Henrietta Hawk.

Harrelson hoisting bats for the Red Sox

“Hey, Slick,” Hawk recalls saying. “Why don’t you lay off?”

“I’ll drop the Henrietta when you get a hit,” Howser countered.

“Well, I started hitting,” Harrelson says, “and he did.”

Harrelson soon started thinking of the Hawk as a kind of alter ego—a hungrier, angrier version of Ken. It was the Hawk who got him to the big leagues, first with the Kansas City (now Oakland) Athletics in 1963 and later with the Boston Red Sox in 1967. In Beantown, it was the Hawk who gave him a breakout year—35 home runs and 109 RBIs—a season that earned him player of the year honors and a spot on the American League All-Star team.

“I can remember a lot of times on the on-deck circle in Fenway, a big game, and a man on third and one out or something, and Yaz [Carl Yastrzemski] would pop up,” Harrelson tells me. “I’d say, ‘All right, Kenny, get out of the Hawk’s way and let him go.’ The Hawk used to love that kind of stuff, when the game was on the line. Ken didn’t love it. Ken was scared shitless.”

While the blessing of his alter ego was confidence, the curse was temper—and occasional bad judgment. He married his high-school sweetheart, Betty Ann Pacifici, when he was just 17; the marriage was stormy. For a while, he raced hot rods, risking his neck on bush-league tracks in rural Georgia (he quit after almost killing himself in a $100 match race). He would fight “over nothing,” he says, including a bloody bar brawl in 1964 in Caracas, Venezuela, where he was playing winter ball for the A’s. Despite Harrelson’s pleas for leniency (“I’m a baseball player—El Hawko,” he told a desk sergeant), he was tossed “in a little cell that must have had 40 people in it, screaming and cursing and fighting.”

The Hawk persuaded him to agree to a 1967 publicity stunt by the owner of the A’s, Charley Finley. He rode a mule named Charley O. around Yankee Stadium. (“Roger Maris threw a bat and hit the mule in the ass and he started bucking,” Harrelson recalled in the 1986 Chicago article. “I swallowed my tobacco and all of a sudden I swung underneath the mule and then those long teeth of his were about this far from my nose and I just knew he was going to bite it off.”)

It turned out that he had more to fear from Finley. After Harrelson publicly criticized him for letting manager Alvin Dark go later that year, Finley released him from the team in a fury.

But what had seemed like a reckless move on Harrelson’s part paid off in a way that sent the Hawk—and Harrelson’s ego—soaring. His firing made him, in effect, baseball’s first free agent. He took full advantage, inking a hugely lucrative deal with the Red Sox that included a then-unheard-of $150,000 signing bonus.

In Boston in those days, Harrelson was almost as big a rock star as Mick Jagger. An avowed clotheshorse, he reveled in the part. “My hair was long, my clothes were sensationally different. I spent money as fast as I got it—and sometimes faster,” he recalled in Hawk. He showed up one night at a Boston Bruins game wearing a gold-and-white silk brocade suit with a Nehru collar and Edwardian lapels. The pants had 12-inch pleats. The shoes were made from the same material as the suit.

Boston was loving the Hawk. “The Red Sox were looking for a personality,” Harrelson says. “And it happened to be me. Wherever I went, writers, radio-TV people, photographers [mobbed me].” For one of his many television appearances at that time, he donned a blue sateen jacket, a white turtleneck, gray slacks with blue pinstripes, white shoes, and love beads. He also favored a heavy gold medallion on a gold chain, which he sports on the cover of his memoir.

Though by now he was a married man with four children, Harrelson decorated his pad bachelor-style: orange walls, black ceiling, white rugs. A sculpture of a big hawk clutching a rat sat on the counter of the bar. The backyard featured a multicolored fountain. His wheels? A tricked-out lavender dune buggy with velvet trim, four-inch-thick white carpeting, a bar, a small refrigerator, and a record player in the back—decades before MTV would dream up Pimp My Ride. As he notes in his memoir, the word “Hawk” was embroidered on just about everything he owned: “my slacks, my sweaters, my shirts, my jackets, my underwear, my baseball gear, and my car.”

Legends were growing around him. In his downtime, Harrelson had become one of the best golfers in the major leagues. After hitting the links one day before a game, his hands were blistered, so he wore his golf glove to bat. Today the batting glove is as integral a part of the game as the seventh-inning stretch, and it was Harrelson who invented—or at the very least popularized—the practice.

He was also way ahead of the curve in the trappings of celebrity. “To my knowledge, I was the first athlete to have a bodyguard,” he says.

Despite Harrelson’s popularity in Boston, the Red Sox, desperate for pitching, traded him to Cleveland in 1969. Devastated, he threatened to retire but eventually capitulated. He had a decent first year there, but a serious injury the second year (he broke his leg during a spring training game) helped him decide to quit the sport in 1971. (His marriage was crumbling too; he and Betty Ann would divorce the next year.)

Harrelson then took a step that few athletes would have attempted: He went pro in a different sport, trying to make it on the professional golf tour. Despite some success—in 1972 he played in the British Open, one of golf’s major tournaments, and won several small events—his habit of flying into rages held him back. “I’d go out with 14 clubs and come back with 5 or 6,” Harrelson says. “One reason I quit golf was because I was embarrassed.” Once again, he refers to his alter ego: “I couldn’t control the Hawk.”

* * *

Photography: (top) AP Photo; (right) copyright Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images

Harrelson cutting a fine figure

Harrelson had also become one of the first sports celebrities to open a nightclub—a place on the water in East Boston that featured a floating cocktail lounge. But it caught fire in 1971 and never reopened. Casting about for some other way to make a living, he decided to reinvent himself yet again: as a broadcaster.

He parlayed his popularity in Beantown into a job with the Red Sox in 1975, working with the veteran sports announcer Dick Stockton. Viewers today might not recognize the down-the-middle delivery: Harrelson had not yet honed his combative, flamboyant style.

In fact, when the White Sox hired him in 1982, pairing him with the pitching great Don Drysdale, he was given express orders from owner Jerry Reinsdorf to play it straight. “I told them, ‘I do not want you rooting on the air for the home team. I want this to be a network-quality broadcast,’ ” Reinsdorf says. “So that’s what they gave me.”

The response? “Our fans were up in arms,” Reinsdorf answers with a laugh. “The Chicago market wants a homer. That’s why he does the homer routine. I personally don’t like it, but that’s what our fans want.”

Suddenly free to test his wings, Harrelson began developing his signature style, drawing many of his now-clichéd terms—such as “Stretch!”—from things he’d say on the golf course. He also began to let loose his inner Hawk. His pairing with Drysdale, for example, was sometimes volatile. “He would get hot, and I would get going,” Harrelson recalls of their epic arguments. “We almost got in a couple of fights. I stopped the car one day in Cleveland. Top down, let’s go. I’m glad we didn’t.”

Then, in 1985, he and Reinsdorf made what they now both describe as the worst decision of their careers. Reinsdorf hired Harrelson as the team’s general manager. “I bought the team in ’81, but in ’85 I could see that our farm system was barren,” Reinsdorf explains. “There were a lot of things that really weren’t being done right, and Hawk pointed out a lot of these things to me.”

The move proved “disastrous,” recalls Reinsdorf—though both can laugh about it now. Among the mistakes Harrelson made were two colossal blunders: firing Tony LaRussa, who would go on to become one of the best managers in the history of the game, and trading Bobby Bonilla, an eventual six-time all-star. “I should have fired Hawk then and put him back in the booth,” Reinsdorf says, not unkindly. “As a general manager, he was a great announcer.”

General manager is “the worst job in baseball,” Harrelson says. “Twenty-five hours a day, eight days a week.” He knew it was time to quit when he saw his daughter, Krista, then 10, weeping over an article ripping him. “I looked at the paper and saw what she was reading, and that’s when I made up my mind: I’m outta here,” he says.

After a year as play-by-play man for the New York Yankees and a backup broadcaster for NBC’s Game of the Week, Harrelson was rehired in 1990 by the White Sox. It was at that point that he was paired with his best-known partner by far: Tom Paciorek, a former big-league player who teamed with him for 11 years in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s.

“Hawk and Wimpy” became synonymous with the Sox, with Harrelson doing the play-by-play and Paciorek acting as the singsongy, voice-cracking sidekick. The two often traded gentle jabs, but most of the time it was Harrelson doing the hitting. Still, the chemistry worked. “He was wonderful to work with,” Paciorek tells me. “I’m a lot more shtick than he is, and he had his sayings and catch phrases. He really knows the game.”

While his rougher edges seem to have smoothed out, Harrelson concedes that to this day he still struggles with his volatile side—the Wegner tantrum being the latest example. “Sometimes it happens in a broadcast,” he says. “With a certain play. Or maybe an umpire makes a bad call. I sit back and get pissed off at [the Hawk] because it’s not me, it’s him. And it’s been that way all my life.”

When I ask Harrelson about the criticism—if it bothers him to be such a polarizing figure—he chuckles a little. “Nah,” he says in his distinctive twang.

“Listen, I’ve been ripped and knocked and made fun of for most of my life, whether it’s been as a ballplayer, golfer, announcer, whatever,” he told Chicago in 1986. “And over the years you start to understand more about yourself and the system, and those things hurt less and less. You build up—it’s not immunity; I don’t think anyone’s ever immune—but you built up an understanding of why.”

Harrelson’s colorful personality, like it or not, is his greatest strength, Stone and others insist. “The worst thing you can say about any broadcaster is that you’re indifferent to him,” Stone says. “When you have a unique style, as [Hawk] does, you’ll find some people who really dislike it and other people who absolutely love it. For every person who does criticize him, you’ll find I don’t know how many Sox fans who absolutely adore him. There really is never going to be another Hawk, and that’s one of the reasons I believe he will make the Hall of Fame in the next two or three years.”

ESPN Chicago’s Bruce Levine, a longtime baseball reporter, agrees. “Whether you like him or not, you’re always paying attention to him. That’s 95 percent of the success ratio for a broadcaster. Has he become a caricature of himself in some ways? Maybe, but the only way people can become a caricature of themselves is if they’re iconic to begin with.”

The generation to whom Harrelson is iconic for his sixties grooviness would hardly recognize his lifestyle these days. He says it’s “180 degrees” different, largely thanks to his second wife, Aristea. The couple live in low-key Granger, Indiana, a two-hour drive to the ballpark; Harrelson is very focused on Aristea, his six children, and his two grandchildren. His son Casey, 34, has followed in the old man’s footsteps. He’s a professional golfer who once played in the White Sox farm system.

And yet anyone who sees how agitated Hawk still can get when working a ball game can tell that he hasn’t fundamentally changed and likely never will. “To me, baseball is an emotional game,” he says. “It’s a game of passion. There’s not one person in this stadium tonight or one person who has a White Sox uniform on that hurts more than I do when we lose a game or is happier if we win. That’s just the way I’m built. That’s just the way I was built by my mom.

“I am proud to be known as the biggest homer in baseball,” Harrelson continues, a broad smile spreading under the big beak. “Proud to be. I wear that as a badge of honor.”

* * *

The game has become a pitchers’ duel. For most of it the Hawk has been dormant. Then a Sox player is called out on strikes on a questionable checked swing. On air, Harrelson clenches his jaw but doesn’t launch into a tirade—a remarkable moment of restraint. “We had a chance there in the bottom of the eighth,” Hawk says when the broadcast returns from a commercial break. “But we got a bad call.”

And now, trailing 2 to 1 in the bottom of the ninth, the Sox are down to their last two outs. “C’mon, Alexei!” Hawk barks. “Aw, got a cookie right there and couldn’t do anything with it,” he says. Orlando Hudson grounds out to end the game. “And this ball game,” Hawk says, voice strained with irritation, “is ovah.”

Both he and Stone immediately pack their glasses, notes, and other belongings into briefcases. Harrelson has been gracious—not to mention garrulous—all night. But now he barely says a word as I follow him through the back hallways, down a staircase, and into the locker room, where reporters crowd around Jake Peavy, who pitched superbly, asking what went wrong.

It’s just another game, but he can’t stand it. Dadgummit.

Harrelson disappears for a moment, then returns, his loafers flapping. He gives me his cell number and, beak-first, heads out the door. It’s a long two hours to Indiana.

Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis