Richard Melman owns or operates nearly 75 restaurants, most in Chicago but many with branches in half a dozen U.S. cities. His dining rooms offer a startling range of food, from pizza and burgers to haute cuisine. The company he founded, Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, employs 5,500 people and pulls in about $325 million in annual sales. That number will likely take a big jump if Melman succeeds in his current plans, which include the purchase of several smaller restaurant companies.

More drama awaits the opening of new Lettuce restaurants. Frankie’s Scaloppiné—the group’s first-ever spot focused on pounded meat and fowl—is about to go into business on the sixth floor of the Bloomingdale’s building at 900 North Michigan. Papagus in Oak Brook will soon be reincarnated as The Reel Club, a seafood spot. A Lettuce legend—he won’t say which—will get a top-to-bottom rehab and emerge as . . . to be determined. Melman’s temple of fine dining in Lincoln Park, Ambria, served its last canard this summer and will soon be a totally revamped high-end seafood restaurant with Laurent Gras as chef. And Melman’s two sons are slated to open their own Lettuce restaurant early in 2008.

This burst of activity merely underlines the obvious: Melman is more than a restaurateur. He is a man who understands people and the currents of a culture. He is a man who knows how to build an empire. Would his savvy and experience apply to any budding entrepreneur in search of fame and fortune? With that question in mind, we spent time with the man these past few months to gather the precepts that ensure success. The following rules—the Melman canon—are ours, not his.

Photograph: Todd Baxter

1. EXCUSE YOURSELF FROM THE TABLE

The smart restaurateur knows when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em. Two relics of the early Lettuce heyday, Lawrence of Oregano and Jonathan Livingston Seafood, are remembered by a scant few. Decent business could not overcome a fire and a lost parking lot. The outlook was brighter when Melman opened Eccentric on West Erie in 1989. Partnering with Oprah Winfrey, Melman had every reason to expect a hit. In retrospect, he can see why the place did only so-so business. “We were trying to do too much,” Melman admits. “Steaks, fish, American, French, Southern. It wasn’t working.”

A man with a more consuming ego would have slogged on, waited to catch a break, balked at losing the Big O. “I loved Oprah; she was a great partner,” Melman says. “But I knew I’d made mistakes with the restaurant. I messed up.”

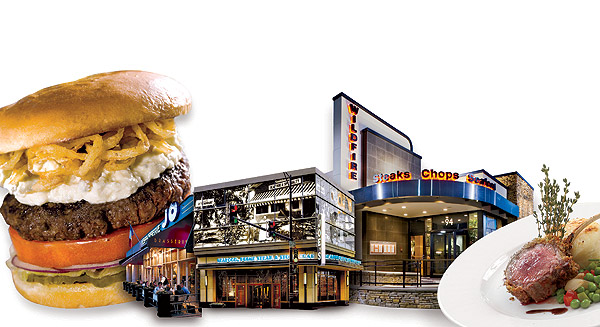

Though under no obligation to do so, he gave all his investors their money back. Folding Eccentric turned out to be a smart move. In its place he launched Wildfire, a nostalgic upscale chophouse that has spread like . . . wildfire. There are five around Chicago, one in Atlanta, one in Minneapolis, and an eighth opens this month in McLean, Virginia, a D.C. suburb.

When Melman pulls up stakes, he often hangs on to the real estate, because location rules at Lettuce. Once he tired of his elegant Italian eatery Avanzare, at St. Clair and Huron, he installed Tru with the haute-renowned team of Gale Gand and Rick Tramonto; when Papagus, the bright, busy Greek restaurant at State and Ontario, ceased to captivate Melman, he replaced it with Osteria Via Stato, a homey Italian dining room. “Papagus was never a loser,” says Melman, “but it was never a big winner, either. It was a single, not a home run, and we don’t stay with singles too often.”

Osteria itself is about to cede turf to a designated hitter. Seems 20 people a night would stop by the restaurant bar and ask, “Say, where can I get a good pizza around here?”

“We finally woke up,” says Melman.

The Osteria bar was gutted and was scheduled to open in November as Pizzeria Via Stato, serving crisp, thin-crust pizza loaded with fresh ingredients. Melman had no intention of offering wood-burning oven pizzas, he says with a rare trace of scorn. He did, after all, pioneer the wood-burning oven in Chicago at Lawrence of Oregano—and he doesn’t like to repeat himself.

Photography: Courtesy of Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises

2. REFRIGERATE THE DOUGH

2. REFRIGERATE THE DOUGH

Rookie cooks hungry for results roll out the pastry and slap it into a tart pan. This is a mistake. The dough needs time to rest and recover. Otherwise it will be a soggy mess and won’t support the filling.

Patience, in other words, can be vital. Ideas, like dough, should not be rushed. Sometimes Melman refrigerates his ideas for years. It was thus with the bao.

Years ago—20 years ago—he was mulling over business at his restaurant Gino’s East, where friends had waited 45 minutes for the thick-crust pizza to rise and arrive, and then the entire bill came out to eight dollars a person. “That’s when it occurred to me,” Melman says, “that to make money you needed to sell something before everyone got their food.”

The idea went into the file folder that is Melman’s brain (he also keeps actual file folders crammed with scraps of conversation and recipes and newspaper clips). In 2001, Lettuce sold its Big Bowl franchise to the restaurant company Brinker International, then bought back the concept four years later. Immediately the test kitchen began plotting new twists on the Thai noodle bowls and wok-tossed stir-fries that had made Big Bowl such a success.

Why not fast casual Asian fare? thought Melman, recalling the interminable wait at Gino’s. Food that could be ready 30 seconds after the customer paid at the register. “Three weeks later we had the bao.”

The bao is a steamed Asian bun. There are plenty of steamed buns on the carts in dim sum restaurants in Chinatown. But how many people go to Chinatown for lunch? How many are comfortable with bean-curd filling? Melman had a better idea: Stuff the bao with Asian staples more appealing to Westerners? Fillings like Thai chicken and Mongolian beef and pork barbecue? Throw in a few salads; serve fresh juice. Give the place a clean, polished look. Slap on a cute name. Faster than you could say “Wow Bao” there was a bao stand on the ground floor of Water Tower Place, then a sit-down restaurant in the Loop. By November, you will be able to grab a box of baos on the way home next to the busy el stop at State and Lake.

Speaking of dough—it’s likely that Melman could have been a lot richer than he is now. He believes in making money, yes, but he was never a bottom-line guy. Maybe it was all those years he spent in therapy; back in the early days of Lettuce success he talked about nothing but therapy and self-exploration. He liked to try new things. He resisted the idea of franchise, even when businessmen begged him to turn early hits into brand names.

“Rich was never fueled by duplication— that’s one reason he didn’t want to open the same business in other cities,” says Kevin Brown, the president and chief executive officer of Lettuce. “He also didn’t like to travel a lot. He wanted to go home and sleep in his own bed.”

Photograph: Todd Baxter

3. EAT HUMBLE PIE

It sounds like the most trite cliché but, unaccountably, Melman is a regular guy. He wears jeans and sneakers. He is not bombastic. Unlike some restaurateurs who will go nameless, he would never dream of embarrassing his staff. I witnessed this equanimity firsthand during a lunch at Joe’s Seafood, Prime Steak & Stone Crab, his Miami import on East Grand Avenue. Sampling a seafood salad, he paused to extract a small pea-size tidbit from between his teeth. “Cartilage from the crab,” he explained.

Who but Melman would admit to such a gaffe while dining with a reporter? Furthermore, I doubted the chef would be receiving a tirade after I left. Melman is not of the screaming restaurateur school. Demean people, he believes, and they make more mistakes, not fewer. Arrogance has no place in the Lettuce culture or in Melman’s personal ethos. He says things like “It’s the responsibility of the leader to make other people successful” and “The business is not about you. It’s about how we connect to our guests. We’re in the service business.”

Of chief executive officer Brown, he says, “He does all the work and I get all the credit.”

Melman has several high-end restaurants, such as Everest, run by the award-winning chef Jean Joho, and Tru. But you will not find him exclaiming over towers of root vegetables in pools of raspberry sauce. “Give me a nice bread, a salad, and a bowl of pasta,” Melman says, “and I’m a happy guy.”

4. DON’T TALK WITH YOUR MOUTH FULL

Melman knows when to talk—and when to listen. He’ll listen to anyone. Some of his best early ideas came from a guy who worked at the post office. This was back in 1962, well before restaurants were on the horizon. Instead, Melman got bitten by the entrepreneurial bug. He and a buddy pooled their savings, $3,000, and put an ad in the Chicago Tribune: “Inventors Wanted. Will Finance.”

He received more than 200 replies. One was from a man whose name Melman doesn’t even remember, a middle-management mail supervisor who had a bunch of quirky inventions: Christmas candles whose flames burned the color of the wax, red or green; a portable grocery cart that folded into a purse. They met downtown for lunch, where the man lectured Melman about the appalling food he was eating—spaghetti and meat sauce, mashed potatoes with gravy. The man had brought his own dessert—a jar with apples in brown sugar. He preached a more healthful diet. He took Melman to juice bars.

The inventor and Melman eventually lost touch, but Melman never forgot what he had heard. His first restaurant gave a serious nod to healthy eating. The chef was instructed to bake the potato skins, not fry them in oil; the 40-plus-item salad bar, a first in Chicago, was packed with fresh vegetables. The place was called R. J. Grunts, combining the first initials of Melman and his new partner, Jerry Orzoff, a Chicago real-estate agent with deep pockets, and the happy noises that Orzoff claimed his girlfriend made while eating.

Within months there were lines around the block.

Melman also knows when it’s time to stop listening. His post-office pal was ahead of his time in another way: He was a rabid antismoker. He believed that cigarettes caused cancer. So a month after Grunts opened, a crusading Melman declared it a smoke-free zone. After a few months of howling, the ban was scrubbed.

A quarter mile north on Lincoln Park West is Mon Ami Gabi, which would likely not exist today were it not for Melman’s acute sensory perception. The restaurant is in the southeast corner of the Belden-Stratford Hotel. In 1980, Melman opened Ambria in the northeast corner of the building, and he was soon plotting another restaurant across the lobby. Ambria was the luxury French restaurant run by the wizardly Gabino Sotelino, previously the chef at Le Perroquet. Melman frequently dropped by before the dinner rush and was struck by the delighted cries from Sotelino’s staff as they wolfed down their food. What an onion tart! The frites—magnifique! “They were getting the best employee meals in the city,” Melman marveled. Those employee meals would later anchor the menu at Un Grand Café, the previous incarnation of Mon Ami Gabi.

He will listen to anyone with good ideas, especially when it comes to the goofy names for his restaurants. He initially intended to call his company Apple Sauce Enterprises; his wife, Martha, talked him out of it, and she and a girlfriend came up with Lettuce Entertain You. On the long list of candidates for his Chinese bun bistro were Buns on the Run and Hot Asian Buns. His assistant, Ann Johnson, weighed in with Wow Bao.

5. PLAY WITH YOUR FOOD

The headquarters of Lettuce Entertain You are in a bland, one-story building along an undistinguished stretch of Sheridan Road. Melman has a corner office but can often be tracked winding his way through a maze of cubicles and into the test kitchen. He is here one morning this summer sampling menu items for his new seafood restaurant, The Big Reel in Oak Brook.

Amid his crew in chef’s whites, he sits at a table in jeans, digging his fork into each new offering while the staff take notes. The coconut fried shrimp—definitely a winner. The trio of smoked fish? Nice idea—the mesquite-smoked salmon is a keeper—but maybe all three are too much. The plate is so crowded. And what’s with the toast points? Only average, that’s what. And the seviche—the seviche is a problem. “For one thing,” says Melman, “it’s not what people picture when they think of seviche. This is more Indonesian. Let’s work on the marinade.”

But speaking of seviche . . . how about . . . he snatches a pen and paper. He sketches what looks like a cake platter, then draws a second small plate on top. “Maybe a pedestal. Just seviche. And do it tableside.”

Scribble scribble go the staff pens.

“I’m very good at sculpting,” says Melman. “I love to remodel.”

That goes for the architecture of his restaurants and the food served therein and the presentation. When he opened Scoozi! on West Huron Street, the restaurant offered risotto, but who wanted to sit and wait an eternity for rice? Why not make a new batch every half-hour? he thought. Walk around with a pot. If you wanted it, you held out your plate.

For the legendary Grunts burger, he sampled 20 different mustards before settling on a Düsseldorf. For the ground beef, he experimented endlessly with the right mix of choice and sirloin.

He’s out there all the time, digging away with his fork and spoon, updating dishes, making sure his restaurants “evolve,” to use one of his favorite words. Never sit still; keep on changing. “I like to eliminate our weaknesses,” he says, “and replace them with something great.”

For our lunch at Joe’s, he was on a mission. It was time to “freshen up” the salads. Ditching the oval plates was a start. But the special seafood salad didn’t pop enough, with or without the cartilage. And the pies—well, Joe’s is famous for its pies. But pies, like salads, must march ever forward. Responding to the call for new ideas, the restaurant manager presented Melman with the chef’s latest, a lemon-scented blueberry pie under a dollop of whipped cream. “I think you’ll like this, Rich.”

Melman forks up several bites after the manager leaves. “Not bad, but the berries are too clumped. And we need to play with the crust.”

Only the whipped cream meets with his approval. “Everything else,” he says, “needs to be tweaked.”

6. FORK OVER CONTROL

Melman sits atop a big organization. He works hard. But he has an interesting view of management. He believes that giving people ownership of their work increases their motivation. “Everything I’ve ever done I’ve done with partners,” says Melman. “I love partnerships.”

Lettuce has 55 partners. Eleven of those are senior personnel, men and women at the top in charge of marketing, finance, operations. Many of the others manage one or more of his restaurants and have a personal stake in each restaurant’s success. Few sauntered into Lettuce with long résumés. Many had humble beginnings—waiting on tables or taking reservations. Marc Jacobs, 34, one of the bright young stars, oversees the ambitious rehab at Foodlife in Water Tower Place when he’s not running Scoozi! and Antico Posto. He started work at Lettuce as a banquet server and busser.

So did Dan McGowan. He’s one of the senior partners, president of Big Bowl. Before he hosted at Ed Debevic’s, he manned the spotlight at the now-defunct Lettuce comedy club, Byfield’s.

“It’s like a marriage,” says Melman. “It’s better if you get to know each other first.”

Melman rarely hires top personnel from outside the organization. He prefers that his people get familiar with the culture and work their way up. “We like to make sure our passions aren’t misconstrued,” he says.

“If you’re looking for a company that cares just about making its quarter numbers—that’s not us.”

It helps, of course, if you know what you want—and Melman prides himself on spotting talent. His first-ever recruitment trip was in 1977 with his chief financial officer to East Lansing and the restaurant management school of Michigan State. He’d just walked off the plane when a young man hurried up and asked, “Are you Rich?” They repaired to a local eatery called Mountain Jack’s and talked for hours. Melman was impressed but nervous about taxing his budget with too high a salary. In the cab to the hotel, he asked his CFO, “Can we afford $11,000?”

The man, Kevin Brown, got the job—and now he’s the president and chief executive officer.

7. SERVE FAMILY STYLE

Melman has three kids. His two sons, R. J., 28, and Jerrod, 24, are in the business 24/7. Molly, 22, has worked for her dad but currently is a schoolteacher. Keeping it all in the family was not a lesson Melman learned at his daddy’s knee. His father was a restaurateur. He had a bunch of businesses and a well-known deli called Ricky’s in Skokie. Melman put in long hours at the deli. He worked behind the counter; he bussed tables. He had a hankering to join the business, so he asked his father if he could become a partner and buy a 2.5-percent share.

His dad thought about it awhile and then said no. He told his son he “wasn’t ready.” He wanted his son to settle down first and get married. “Getting married was the furthest thing from my mind,” says Melman. “I was working so hard I didn’t have time to date.”

His father’s denial sent him into an emotional tailspin. As Melman puts it, “A light went off.” Three weeks later he left the company and never went back. Melman’s father died in 1985 without any real resolution between father and son. “I never got as close to him as I would have liked,” says Melman. “He wasn’t very affectionate. I told myself if I ever had kids I’d never be like that.”

He met his wife at—where else?—Grunts. Orzoff had been nagging Melman to date. When Melman claimed he was too busy, Orzoff urged him to prospect from the home turf at Grunts, which drew an attractive crowd, and promised to help. Relenting, Melman nodded at a woman waiting in line and said, “OK, she’s really cute.” Orzoff made the introductions, and Martha Whittemore and Richard Melman were married several years later. They named their first son R. J.

R. J. is now the manager at Grunts. The day I had lunch with Melman there, the son stopped by our table to say hello. He seemed relaxed and comfortable. “That picture looks like it fell off the wall,” said Melman, pointing to a framed photo at a far booth. Above it was a foot of white space.

“Actually,” said R. J., “I think it’s always hung like that. But let me go find out.”

He returned to explain that the photo was hanging properly, but he would raise it. How is it to work with his father? Just fine, he said. “I was lucky enough to begin my career outside his scope, in Minneapolis, where I could develop my own style and confidence. Now that I’m back he can trust me to make the right decisions.”

Jerrod initially had thoughts of becoming a standup comic. Toward that end, he spent time as a dishwasher and busboy at Second City. “Apparently it cured him,” says his dad with a smile. “He decided being around all those comedy people wasn’t so glamorous after all.”

Jerrod is now doing apprentice work with a few of his dad’s restaurant pals in New York City. In February, he and R. J. will be opening a restaurant together, Hub 51, in River North.

Melman has never pressured his kids to become Lettuce heads. “The restaurant business is hard,” he says. “It’s a mistake to get into it unless you love it.” Now that two of them are, he’s thrilled.

“They’re part of a whole new generation of future leaders at Lettuce,” he says. “There are maybe 20 in all areas, from accounting to food. R. J. and Jerrod are certainly two of those leaders.”

He’s reluctant to characterize the specifics of Hub 51 beyond saying, “It’s American but a lot more than American. People are going to go crazy for the food. It’s for their generation of 20- and 30-year-olds. It’s their R. J. Grunts.”