At times, it seems like everything fashion designer Virgil Abloh touches turns to cool. Not just contemporarily en vogue, but a cool that channels decades of historic cools. Take the Rockford native's 2017 collaboration with Nike, "Ten Icons Reconstructed": a line of vintage sneaker designs in clean white, embellished with red zip-ties and self-referential lettering—"shoelaces," "air," "vulcanized," "foam."

The punny sneakers call to mind René Magritte's The Treachery of Images—a painting of a pipe with the words “Ce N’est Pas Une Pipe” ("this is not a pipe") scrawled beneath it. Abloh's designs are, in that lineage, surreal and statement-making, referencing both art history and the history of sneaker design itself.

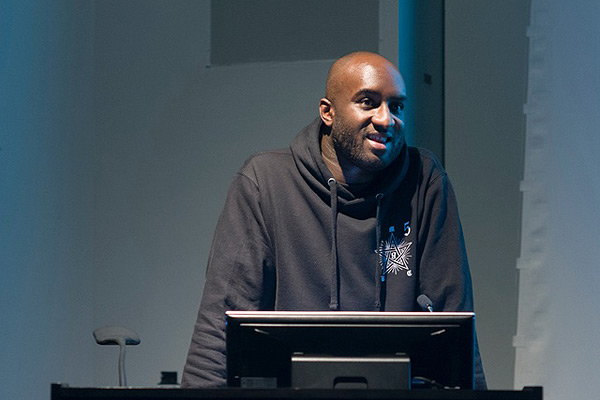

It's heady stuff, but not unexpected for Abloh. The 37-year-old designer, who spent the formative chunk of his career in Chicago, has worked in every thinkable creative field. He's designed furniture for fairs like Design Miami, crafted rugs for Ikea, and most famously, art directed Kanye West and Jay-Z's 2011 album Watch the Throne.

All has led him to his recent appointment as Louis Vuitton’s artistic director of menswear. This exhausting career, however, began here in Chicago where he received his Master’s degree in Architecture from the Illinois Institute of Technology. But Abloh was establishing his cool before he graduated and jumped in a professional architecture practice: he began working with Kanye in 2003, the same year he completed his master's.

Fashion designers often cite architecture as a major influence on their work—Philip Lim credits the residential work of Luis Barragán; designer Michelle Smith has discussed Zaha Hadid’s fluid lines as an inspiration for her sculptural womenswear. But Virgil Abloh has been to the source: IIT’s campus, dotted with exemplary modernist works by Rem Koolhaas and Mies van der Rohe, is known worldwide for its rigorous, critical architecture program.

“[Architects] are here because we solve problems in a structured way,” Abloh told a group of Harvard Graduate School of Design students in 2017. A challenge faced by architects and fashion designers alike is developing a personal design language: a means of communicating meaning and style in a way that is unique to the individual designer. Establishing this language is an exercise in restraint for both architects and fashion designers, and is evidenced by Off/White’s signature black and white striped pattern that reads as straightforward, minimal, and purposeful. It has been edited, restrained, but in a manner that allows for the piece to speak volumes. One could argue similarly for the Miesian glass box.

Abloh, who will be the first African-American to hold the prestigious position with Vuitton, is being celebrated with the hope that he will drive the luxury brand into a more casual-conscious generation. While much of Off/White’s early designs included large and loud elements (logos and textures), Abloh’s more recent work leans toward quiet detailing and multifunctional wearability.

The Off/White showroom in New York City, designed in collaboration with the now-defunct Family Architects, tells a more nuanced story of how Abloh interacts with architecture today. Located at 51 Mercer in SoHo, the signless, small space is considered a “gallery”, as told by Abloh to Architectural Digest in 2017. A garage-style mullioned glass door opens to a narrow white-walled space that hosts rotating exhibitions. The first of which included sapling trees and leaves placed throughout the space that featured more prominently than clothing racks. Exhibitions come down as clothing lines rotate out—a symbiosis of space, art, and fashion. It is functional and minimal, but in its quietness there is an element of surprise.

One of Abloh’s cornerstone ideologies is, “Speak to the tourist and purist simultaneously.” The same idea has thrust contemporary architecture into conversation: understanding that structures and forms should be legible to the broader public while tickling the fancies of architects and architecture historians. Those buildings that, when designed, see the public as being a consumer, can transform how generations experience cities.

By applying it to fashion, however, you get a type of cool that Abloh is pulling off: one that regards urbanity as an identity, that displays an uncanny appreciation of history and form, and wraps you in it in via a hoodie or some new Nike Air Forces.