Two Chicago traditions came together to make history. The Organic Theater Company, a seminal group in the development of small resident theatres on the homegrown drama scene, created a play called Bleacher Bums. Based on an idea from Joe Mantegna, a Cubs fanatic and at that time an Organic Theater actor and ensemble member, Bleacher Bums centers on a group of Chicago Cubs fans whose enthusiasm for their heroes is rarely daunted by the fact that the team almost never wins. Set in the bleachers at Wrigley Field, the play unfolds during a single game. The woe of the characters is immediately recognizable, and remains so today: The Cubs haven't won a World Series since 1908; the team hasn't even played in a World Series since 1945.

At its premiere, Bleacher Bums scored a home run with the audience and became a long-running hit both in Chicago and in other cities. The play has been made into two movies, including one with the original cast, and has had countless updated revivals, among them a 25th-anniversary production with a script revised by the original cast. The play is famous for launching the careers of the actors Joe Mantegna and Dennis Franz; it also springboarded the writer Dennis Paoli and the director Stuart Gordon into movies. The actor Roberta Custer went on to appear in films and has been the personal assistant of the CSI: Crime Scene Investigation star William Petersen on and off for the past 20 years.

"Bleacher Bums is a masterpiece," writes Richard Christiansen, a former critic for The Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, in his book A Theater of Our Own: A History and a Memoir of 1001 Nights in Chicago (Northwestern University Press, 2004).

On the 100th anniversary of the Cubs' World Series win, and with the team off to a good start, we decided to look back at the creation of this timeless play about Cubs fans.

Several of the players in the original production agreed to talk about Bleacher Bums: how it was created and what it meant to them.

Photograph: Stuart Gordon/Chicago Tribune

OUR CAST (In order of appearance, left to right): Joe Mantegna (writer and actor); Richard Christiansen (critic); Stuart Gordon (director); Dennis Franz (actor); Roberta Custer (actor); Dennis Paoli (writer)

|

JOE MANTEGNA: When I was 18 or 19 years old, I'd go to a lot of Cubs games. It didn't cost much to get into the bleachers, and these were all afternoon games, before the lights came to Wrigley Field. And I'd sit there and watch the game. And that was the same time I started to get serious about acting, as well.

Shortly after that, I became part of the Organic, which had a theatre that seated 150 people. And it was a struggle to fill those seats—an effort on everyone's part, no matter how good the play was or how good the reviews were. Then in the afternoons I'd be at this ballpark seeing 35,000 people watching this team that, at best—I mean, I love the Cubs, and I've been following them since I was a kid—was basically mediocre.

Why does that happen at Wrigley Field? I'd wonder. What is it about this that brings people back over and over when, frankly, the "show" isn't that good? If I could capture whatever it is that makes people follow the Cubs and use that to make people follow a play, I'd really have something.

RICHARD CHRISTIANSEN: The Organic Theater was a crucial player in the development of small resident theatres in Chicago, chiefly for its ensemble work and its cultivation of local talent. Stuart Gordon was a native Chicagoan, and the people he gathered around him were, by and large, natives of the city, too. Stuart once told me that to be a good Chicago actor you need improv skills and a sense of humor. And Bleacher Bums turned out to be the masterwork of that process.

STUART GORDON: At the Organic, we would always decide as a company what we would do as our next show. We were a true ensemble group, from conceiving the plays to sweeping the floors. We did it together.

Photography: (Second from left) Charles Osgood/Chicago Tribune; (third from left) Charles Hugare/Chicago Tribune

Actors Michael Saad, Roberta Custer, and Ketith Szarabajka

|

|

JOE MANTEGNA: In the summer of 1977, we had run out of money. There was less than $500. Stuart sat us down together and said, "We don't have any money left. But if anyone has any ideas for a play that would cost us almost nothing, we're open to it." So I raised my hand and told everyone about my observations of the fans in the bleachers and my concept of trying to tap into that same kind of audience.

STUART GORDON: Joe started describing these fans in great detail: the blind guy who wanted to be a play-by-play announcer; other guys who were betting furiously on anything that happened in the game; someone who was a complete slob, and they were always trying to throw him out; the geek; the bathing beauty; and the villain who always bet against the Cubs. It was this little community.

And eventually we were all laughing so hard, we thought Joe had to be making this up. And he said, "Come on—I'll take you to Wrigley Field." So we went and sat in the bleachers. And it was all true. This would be our next play.

We decided to start going to the games, and we even took little tape recorders with us. And we would sit behind the people in the bleachers. At first, because of all the betting they were doing, they were afraid we were the police. But after a while, they just accepted us. We never told them we were working on a play. We were in the right-field bleachers, but some of the characters—like the Cheerleader—were based on left-field bleacher bums. They were the ones who really did believe that you could affect the outcome of the plays by doing things like blowing whistles. After the game, we'd come back to the theatre and do improvisations based on what we had just seen.

JOE MANTEGNA: I had a basic idea of who the characters would be, based on these people. And I always knew in my heart that the Cubs would have to lose in the play. That was the whole point. If there could be only one sentence about what the play was going to be about, it should be: Why do you have this adoration and fandom even in the face of repeated failure?

DENNIS FRANZ: The guy I identified with was the most blustery and boisterous person in the bleachers. He was the grumpiest. Everything upset him, and he would totally overreact. He was constantly ready to implode. If we were to do that play today, I probably wouldn't be as drawn to him as I was then.

STUART GORDON: We also worked out a scenario—what each character's story was. The only character we invented was Zig's wife, Rose. We never really saw anyone's wife show up at the park, but we thought it would be funny if one did. And then we broke it down into innings. One of our first ideas was to have the play cover a whole season. Start in April and it would be cold and people would be bundled up to watch the games, and then during the season, it would get hotter and hotter so people would be wearing less. But then we finally settled on the idea that it should be just one game, and that we'd do it in nine innings. I remember we graphed it, with charts. Then based on these charts, we'd do improvisations.

ROBERTA CUSTER: My character, Melody, was a sunbather. I had no interest in baseball, and I didn't want to learn anything about baseball. That was the boys' thing. They were so enthusiastic and young back then—Dennis [Franz] even had hair.

Photography: Stuart Gordon/Harold Washington Library Center

|

|

The director Stuart Gordon communing with cast members

|

|

JOE MANTEGNA: The improv period was maybe four or five weeks, counting previews. Everything came together. Partly that was because many of us had worked together for four or five years at that point. Dennis Franz, Mike Saad, Keith Szarabajka, Ian Williams, Carolyn Purdy-Gordon, Richard Fire, Roberta Custer, and Josephine Paoletti. I was a "new guy," and I'd been there for five years. And we had help. Stuart brought in Dennis Paoli, who structured the script.

DENNIS PAOLI: Stuart and I had gone to Lane Tech High School together, and then we'd been roommates at the University of Wisconsin. By 1977, I had moved to New York, but I was a lifelong Cubs fan: the afternoon games, the sun in the bleachers, the beer, the 12- or 14-inning games. He knew I knew the experience.

When I got involved, they had an actual game in mind. And all the actors had to see where the ball went; they all had to react at the same time. And they had their characters, and they had [transcriptions from] seven hours of improv tapes. It needed a bit of structure, tinkering, really, to make sure that the play was organic—to coin a phrase. I was able to help a little, so I have an additional dialogue credit. The technical structure wasn't complicated. The play had one light cue, which was all it needed: "It is a brilliantly sunny day."

JOE MANTEGNA: We could do this play for next to nothing. For costumes, we went to Amvets, the nearby thrift store, and on Tuesdays and Wednesdays they had half-price day. So we got shirts for a dollar and shoes for 50 cents. I borrowed a sound recorder, a Nagra, that they use in movies. And I recorded a whole game's worth of crowd noise at Wrigley Field. During the play, the tape would run under the bleachers, and the audience would just hear this murmur. But it was really Wrigley Field. And the set was easy: We were working out of the Leo A. Lerner Theater on Beacon Street in Uptown, and it was designed with seats on concrete tiers. So if we took the seats out of one section of the tiers, we would have natural bleachers. We put folding chairs on the stage, and the audience could fill up the rest of the seats in the arena and also sit on the stage. And we would perform the play up in this one section of the seats.

STUART GORDON: We hoped it would be a success for the Chicago audiences, because we were all about creating theatre specifically for Chicago. But we never dreamed of it being a big national hit. We had three weeks in August to fill before we had to go on a scheduled tour to California, Philadelphia, and New York with other plays. We thought this would do the trick.

JOE MANTEGNA: The first time we did it for an audience, the audience went nuts. It was unbelievable. People went crazy. It was an overnight sensation. The next day, the word was out. People had to come. Some of these people had never been to a play in their lives, and they were calling the theatre, asking what they should wear.

RICHARD CHRISTIANSEN: Nothing could prepare you for the real exuberance and joy in theatre that Bleacher Bums provided. To this day, I can remember little bits of dialogue and actions from when I first saw the play. It wasn't just a clever distillation of some of the characters found in the bleachers in Wrigley Field. The play exuded a whole aura of being alive and happy and enjoying being part of a group activity. And the connection between the audience and the actors was incredible.

JOE MANTEGNA: We had captured some of that magic I used to think about. Here is the irony: The Cubs were doing great in the summer of 1977. On the play's opening night, they were in first place. Then they fell out of first place and never recovered the rest of the season. But we had a hit.

ROBERTA CUSTER: If I had realized then I was going to spend most of the next two and a half years onstage in a swimming suit, covered in that orangy Man Tan stuff that stained my palms—and then I had to cover myself with Bain de Soleil every night—I might have thought about what I was getting into. I ended up taking carotene pills from France to keep up the orange color.

Photography: (Image 1) John Austad/Chicago Tribune; (Image 2) Robert Langer/Chicago Tribune

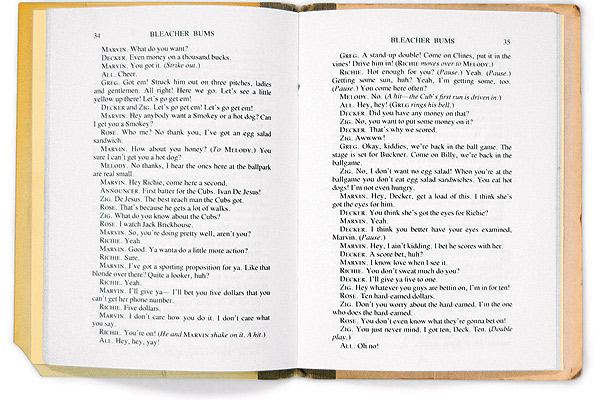

The script

JOE MANTEGNA: Putting the play together, we had talked to Jack Brickhouse, the Cubs announcer. And he had told us this story about his fantasy dream game. We turned that into part of the speech that Mike Saad, playing the blind guy, gives near the end, when Marvin, the villain of the play, offers him a ride home. Mike says, You know what, Marvin? The Cubs are going to win tomorrow, and they're going to go on and go to the World Series, and the Sox will win, too. And it will be a subway series, and Ernie Banks will be called out of retirement, and he'll hit a home run that will land in my lap. And that's when you can take me for a ride. That speech came from Brickhouse—it was verbatim except for the last line. So the night Jack Brickhouse came to the play was a special night. Just to see his reaction.

Another great night was when Ronnie "Woo Woo" Wickers came. You know who he is? He's famous! He's a black homeless guy who stands up in the bleachers and reads out all the Cubs' names and yells this high-pitched "woo" after them: "Sanderson-woo! Beckert-woo!" On and on. Ronnie Woo Woo is legendary. We incorporated elements of Ronnie Woo Woo into the Cheerleader character. So one night Ronnie Woo Woo comes to the play. And when Keith would do his bit yelling out the players' names with "woo!" after each name, Ronnie Woo Woo started joining in from the audience. And the audience went crazy, because lots of them knew it was the real Ronnie Woo Woo.

We invited all the real people from the bleachers to the play, and they were moved by it. I was this character Decker, one of the gamblers, and he was based on a guy named Becker. I remember Becker's wife came up to me after seeing the play. She hugged me and said, "I don't know whether to hug you or sue you." And the guy we based the villain, Marvin, on—the guy who says in the play, "Nobody ever went broke betting against the Cubs after the 4th of July"—he came up afterward,

too, and he said, "Wow, it was great. Now, which character was I?"

DENNIS FRANZ: All the people these characters were based on were pretty flattered by the play. The exception was my guy. I heard he was steamed. He was definitely not happy with the way he was played. Which would have been completely in character.

STUART GORDON: After three weeks of Bleacher Bums in Chicago, we went on tour. And when we were at the Annenberg Theatre in Philadelphia, doing the play The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, the theatre people asked us about Bleacher Bums. They had heard about it and wanted us to do a performance of it while we were there. And we questioned whether that was a good idea or not. Could an audience that was not Cubs fans appreciate the show? Could it be understood outside the culture of Chicago?

We did the performance, and the reaction was fantastic. Unbelievable. So we started to realize that this show was much more universal than we had ever imagined.

JOE MANTEGNA: After Philadelphia, we did Bleacher Bums for two weeks in New York, at the Performing Garage in SoHo. And it was a critically huge success. We got a review from The New York Times that read like it was paid for.

We got reviewed in Sports Illustrated, and I loved it because I knew it was the only way I'd ever be covered in Sports Illustrated. That's when we knew that the play would translate to any audience. It wasn't about the Cubs—it was about the fans. It was about following the underdog.

STUART GORDON: A group of Russian artists and critics were once visiting Chicago, and they came to a performance. We had no idea what they were going to think about it because they don't even play ball in that country. And they loved it. One of them came up to me afterward and said, "This is not about baseball; this is a play about hope."

Which, I think, is exactly right. If you're a Cubs fan, it's really all about hope. So maybe this year, with this team, the curse is finally gone? Maybe it's like Sleeping Beauty finally waking up? It would be wonderful. And in a way, it would be the end of the play Bleacher Bums.

JOE MANTEGNA: Believe me, if the Cubs do win it all, I will be the happiest guy in the world. I'll be the first one to say, "That's it. Bleacher Bums now becomes a period piece. It has no more relevance." He stops talking and makes a sighing sound: Aaaarrrrrrggggggggg. Then he says, "I'm not holding my breath."