For the past 40 years, Chicago has always had three Black representatives in Congress, symbolizing the power of the “Black Metropolis” that elected Harold Washington mayor. We have sent more African Americans to Washington than any other city.

In the past decade, though, Chicago’s Black population has fallen 14 percent, part of a long-term decline that could reduce it from 1.2 million at its peak in 1980 to 665,000 by 2030. Chicago may still have three Black representatives — Bobby Rush, Robin Kelly, and Danny Davis — but it no longer has three Black-majority congressional districts. Rush’s 1st District, which has been represented by an African American since 1929, longer than any other in Congress, has held steady at 51 percent Black since 2010. Kelly’s 2nd District is actually up 1.5 percentage points in Black population, to 57 percent, because she represents the south suburbs, which have absorbed many Blacks leaving Chicago. But Davis’s 7th District, which encompasses the shrinking West Side and the booming Loop, is now only 47 percent Black, down from 54.6 percent.

The Voting Rights Act guarantees minorities representation commensurate to their numbers, but has the moment come when Black politicians no longer have the numbers to hold on to their traditional seats of power? It’s not just Congress: In the Illinois General Assembly, 10 districts drawn with Black majorities after the 2010 census now have a minority of African Americans. The population loss has been magnified by a 2020 census that experts believe undercounted Blacks and Latinos even more than usual. “Danny Davis’s district is in trouble,” says Alden Loury, WBEZ’s senior editor covering race. “He’s been in that seat forever, but it’d be a lot harder for a lesser-known Black candidate to win.”

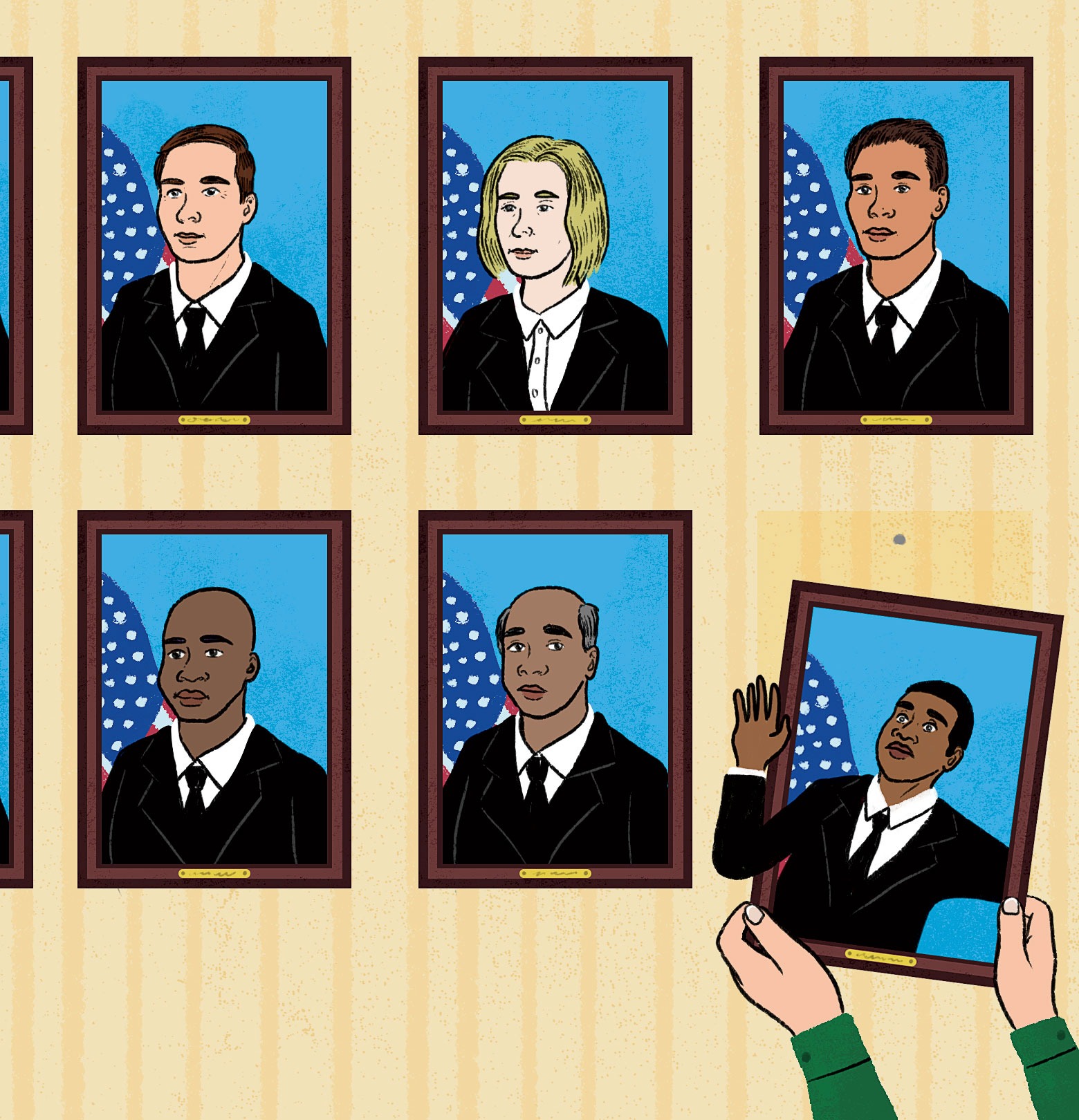

Blacks have already lost ground on the City Council. The 2nd Ward, which had been represented by an African American for nearly a century, was won by a white candidate in 2007 and has had a white alderman ever since. The 15th Ward, on the South Side, is now represented by a Latino. Loury can foresee further loss in the South Loop and the West Loop, where white gentrifiers have replaced African Americans. Non-Hispanic whites surpassed Blacks as the largest racial group in Chicago in 2010; they now make up a third of the population, compared with 28.5 percent for Blacks.

Not surprisingly, Black elected officials have announced they intend to hold their ground — and even increase their representation — when congressional, legislative, and aldermanic districts are redrawn. “We’re going to have to work very carefully from the Black Caucus’s perspective to protect our districts,” state representative Sonya Harper said at a virtual panel on the census and redistricting organized by political consultant Avis LaVelle. “We want to ensure that the districts are drawn in a manner that allows for all people to have representation.” In the City Council, 28th Ward Alderman Jason Ervin, chair of the Black Caucus, sees the 18 existing Black-majority wards — out of 50 total — as a “premise” that could be increased to 19 with creative mapmaking, since some of those wards are more than 90 percent Black.

The state legislature and the City Council have a certain amount of wiggle room: State law allows mapmakers to draw low-population districts for the purpose of preserving minority representation. In the 2011 City Council remap, many South and West Side wards wound up less populous than North Side districts for that reason. There are no such allowances for congressional districts, which must be equal in population. And as a result of the 2020 census, Illinois will lose one seat in Congress, down to 17.

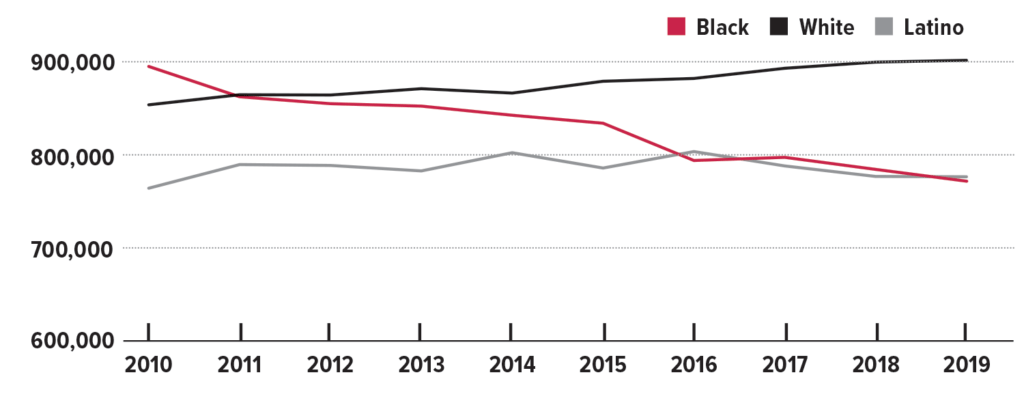

Population Swap

At the beginning of the 2010s, Blacks made up the largest racial group in Chicago. Over the past decade, they’ve fallen to third, behind whites and Latinos, imperiling their political representation.

Nonetheless, U.S. representative Kelly thinks it’s possible to maintain three Black congressional districts — and even add a Latino district. “There is concern about the seats of mine, Bobby, and Danny’s, and the importance of those seats, and who we represent,” she said at the census and redistricting panel. “I think that everything will be done to make sure those seats remain. The Latino population has grown, and they have one seat, which is Chuy García. From my understanding, they’re looking at their population, and possibly having two seats. It’s going to be a delicate balance.”

When the Better Government Association asked demographer Rob Paral to produce a nongerrymandered congressional map, he managed to create three Black-majority districts, but Paral says each was at “barely 50 percent.” However, he argues that Black-majority districts are no longer as essential to electing Blacks as they were in the 1980s, when Chicago’s politics were racially polarized. Two Black aldermen — Matt Martin and Maria Hadden — represent North Side wards. Mike Simmons, who is Black, was appointed to replace a white state senator on the Far North Side. “With the Black population loss, it makes it harder to draw a Black-majority district,” Paral says. “It doesn’t mean you can’t elect a Black official.”

Minority politicians don’t think a few North Side victories make the Voting Rights Act unnecessary. Two Latino aldermen were elected on the North Side in 2019, but that was the result of “anti-incumbent sentiment,” said Alderman Roberto Maldonado, chair of the City Council’s Latino Caucus. Over the past decade, Latino growth in the city has been fairly flat — an estimated 2 percent — but Maldonado thinks there are opportunities to add two Latino-majority wards on the South Side in the remap. “My interest is to make sure Latinos get the number of slots we deserve,” he says. “That is the spirit of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. To pretend that we are a colorblind city, I don’t live in la-la land. Nobody will convince me that given standard political times, without the intensity of emotions against incumbents, Maldonado will beat Smith.”

Which is why Black and Latino politicians are going to fight to maintain the power they’ve gained in Chicago over the past four decades — whether the numbers add up for them or not.

Comments are closed.