My first day in the cockpit as a fully qualified U.S. Air Force pilot fell on a Tuesday. I’d completed my initial training the Saturday before and had been paired with an experienced lieutenant colonel who had a full head of gray hair. We called him the Silver Fox, and he was not there to amuse us. He had high expectations and a reputation for liking to fly with the “green beans” — as newly minted air force pilots like me were called — to make sure we wouldn’t get the idea that the stress was over. On the contrary, he wanted us to know, it was just getting started.

At McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey the day before, we’d meticulously planned out a six-hour sortie consisting of maneuvers and exercises off the Atlantic coast. Our aircraft, a KC-10A tanker, could hold 340,000 pounds of jet fuel and was designed for “force extension” — refueling fighter jets in midair to bring them closer to the forward edge of a battle area. When we took off, around 6:45 a.m. the next day, we had no inkling that the battle area would be over New York City.

One of the truths about being a pilot is that the learning never stops, no matter how seasoned an airman you become. The lessons from that day’s flight remain with me even now, years after my departure from the air force and my move to the Chicago area, where I fly private jets, volunteer at Tuskegee Next, a foundation that helps at-risk kids get on track to an aviation career, and work in private equity.

The schooling began right away that morning. During the first couple of hours of our mission, I was the PNF, or “pilot not flying,” meaning I was handling everything outside of aviating, including the radios, which were keeping me busy: communicating with our sister KC-10A, listening to air traffic control on VHF, monitoring McGuire command post communications on UHF, working the intercom we used for talking to other crew members, and so on. A little after 9 a.m., we received a radio communication from the Eastern Air Defense Sector of NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command), call sign Huntress. Twenty years later, I can remember the words of Huntress precisely: “Team 22, say your state.”

A proper response to that prompt would have been “Team 22, Whiskey 107, Angels 26, heading 090, five plus 15 fuel, four souls on board, fully operational” — our state being the current status of the aircraft, including our position, crew complement, fuel remaining, and operational capability.

Instead, I replied, “New Jersey.”

Another thing you learn about flying is to always sound professional on the radio: Be brief, but not too curt, and above all, don’t embarass yourself, your superior officer, or the United States Air Force. I had managed to do all three. More than 100 combat missions later, I still cringe at the memory of it.

At that, the Silver Fox immediately transferred aircraft control to me and responded properly to Huntress, who then directed us to contact the New York Air Route Traffic Control Center and proceed directly to the airspace above John F. Kennedy International Airport and await further instructions. I didn’t have much experience, but I had enough to know that it wasn’t normal for a KC-10A crew on routine maneuvers to be hearing from NORAD, which is responsible for countering threats to the country’s sovereign airspace. At this point, the lieutenant colonel turned to me, his expression as serious as I’d ever seen it, and said, “I think someone detonated a nuclear weapon somewhere in the United States.”

My first thought was that he was pulling some type of new-guy initiation prank — that he wanted to say something truly hyperbolic and outrageous to see how I would react. It wasn’t until the New York air traffic control center radioed, clearing us to JFK at “pilot’s discretion, 5,000 to 50,000 feet,” that the weight of the moment hit me. We were flying over some of the busiest airspace in the world; below us was Newark International, LaGuardia, JFK, and Teterboro, to say nothing of all the morning air traffic flowing in from Europe, through Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. “Pilot’s discretion 5,000 to 50,000 feet” could only mean that all that traffic was on the ground or diverted. This was not a prank.

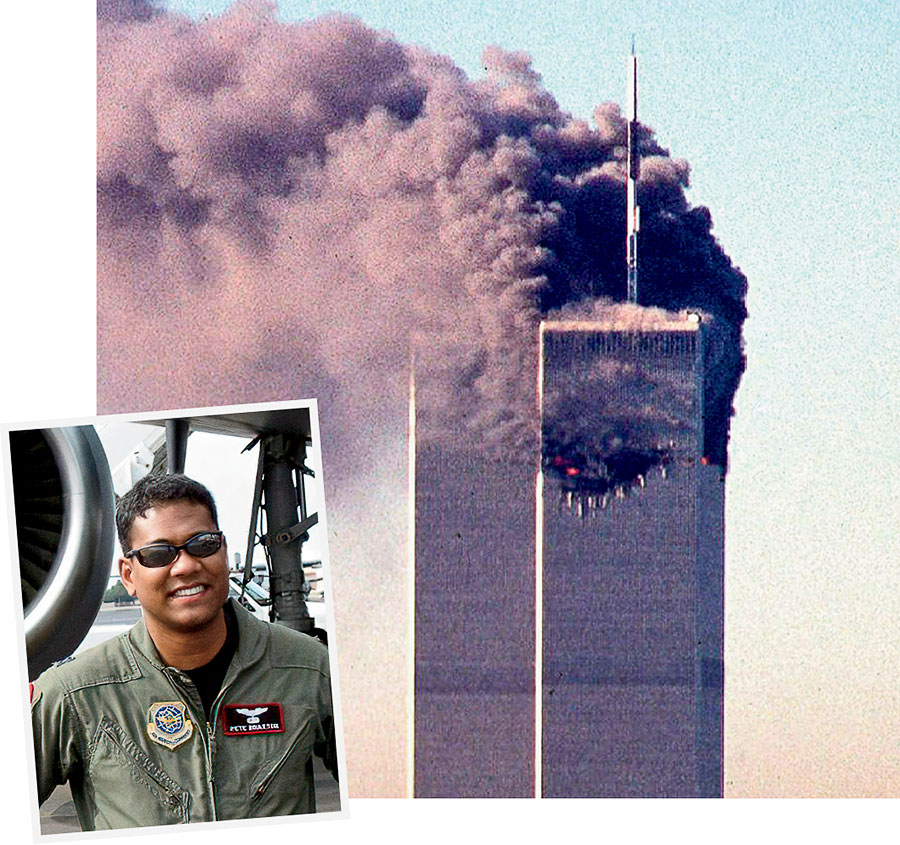

It was a clear day, and as we headed to JFK from our military operating area off the New Jersey coast, I could see the smoke billowing up from lower Manhattan. There were no other planes in sight — we were the first military aircraft over the city after the two airliners slammed into the twin towers. But we didn’t know that: There was no internet in the cockpit back in 2001. And while I had the sense there were injured and dead below, we had zero information about what had happened.

Anyone who’s watched a political thriller knows the phrase “need-to-know basis” — well, we technically didn’t need to know. In fact, it was better we didn’t. If one of my parents or siblings had worked in the World Trade Center, I would have been consumed by worry and, as good as my training was, my concentration and compartmentalization would have been compromised. At that moment, we needed to be an uncompromised military instrument of national power.

I maintained our air refueling orbit over JFK while the Silver Fox worked the radios and checklists. The first fighters to approach for refueling were two F-15s from Otis Air National Guard Base in Massachusetts, and as they got closer, I could see they were bristling with live missiles and ordnance — a sight totally new to me, and one that drove home even further the seriousness of the situation. We were their first stop: When fighters take off with all that weaponry, a full load of fuel can make them too heavy to clear a short runway, so the first thing they need to do is air-refuel. After all, it does no use to fly supersonic to a battle area only to run out of gas once you get there.

We spent the day in low-level orbit above New York City. Normal air refueling was usually performed between 20,000 and 30,000 feet. That day, under emergency conditions, we were as low as 12,000 feet. (I would do emergency air refueling only two other times in my career: once in combat over the Korengal Valley in Afghanistan, and once over Alabama because our receiver aircraft was experiencing mechanical difficulties and needed us to descend.)

After a while, our own tanker was refueled by a KC-135, giving us enough fuel to fly into the night, topping up the F-15s and F-16s that were now patrolling up and down the Hudson and the East River. We had no food or water, as we’d originally planned to land by noon.

When we finally received instructions to head back to McGuire, after being relieved by another KC-10, we were put on a straight 30-mile final approach to runway 24 — another unsettling sign of how empty the skies were. After we’d landed, some 14 hours after taking off, and parked on the ramp, I exited the cockpit and opened the cabin door, whereupon I was greeted by an airman in full combat gear — flak vest, helmet, M16 at the ready position. With the utmost courtesy and sincerity, he said, “Sir, I need to see your ID.” I glanced down the side of the 181-foot military plane as if to say, “Isn’t this weapon system identification enough?!” But I kept that thought to myself and pulled out my ID, and the airman escorted me and the rest of the crew to a secure room known as an intel vault for debriefing.

“Did you hear any distress calls from United 93, American 11, or American 77?” “Did you talk to United 175?” The questions came fast and clipped, and we answered in the negative — we’d gotten no distress calls on our standard communications frequencies or on the emergency channel we monitor during flight. As we were questioned, we slowly began to grasp the nature of that day’s events.

Finally, at around 3 a.m. on Wednesday, September 12, I made the 45-minute drive to my home in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. There, I turned on the television and got my first look at the unreal images of the attack, which were being replayed again and again on every channel. I’d been one of the first members of the American military to see the tragedy from the air and, I realized, quite possibly, one of the last people in America to learn what had happened.