There was a time, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when it was possible to be buttoned-down and hip. Before the British Invasion, before the Vietnam War, music and comedy were sophisticated and cerebral, not primal and visceral. Cool, not hot. Junior executives and assistant professors donned coats and ties to listen to jazz with complex time signatures, earnest folk trios, and comedians riffing on civil rights, the bomb, and the New Frontier.

In Chicago, the headquarters for that scene was Mister Kelly’s, a 200-seat nightclub at 1028 N. Rush St. Lenny Bruce took the stage there. So did George Carlin and Richard Pryor, before they shed their suits to become, respectively, a hippie and a militant. One of the few integrated venues in town, Mister Kelly’s hosted Ramsey Lewis and Ella Fitzgerald, who recorded a live album there. In those days, Rush Street was nicknamed Chicago’s Bohemia, and its idealistic clubgoers thought they were striking a blow for open housing by buying a ticket to a Dick Gregory performance.

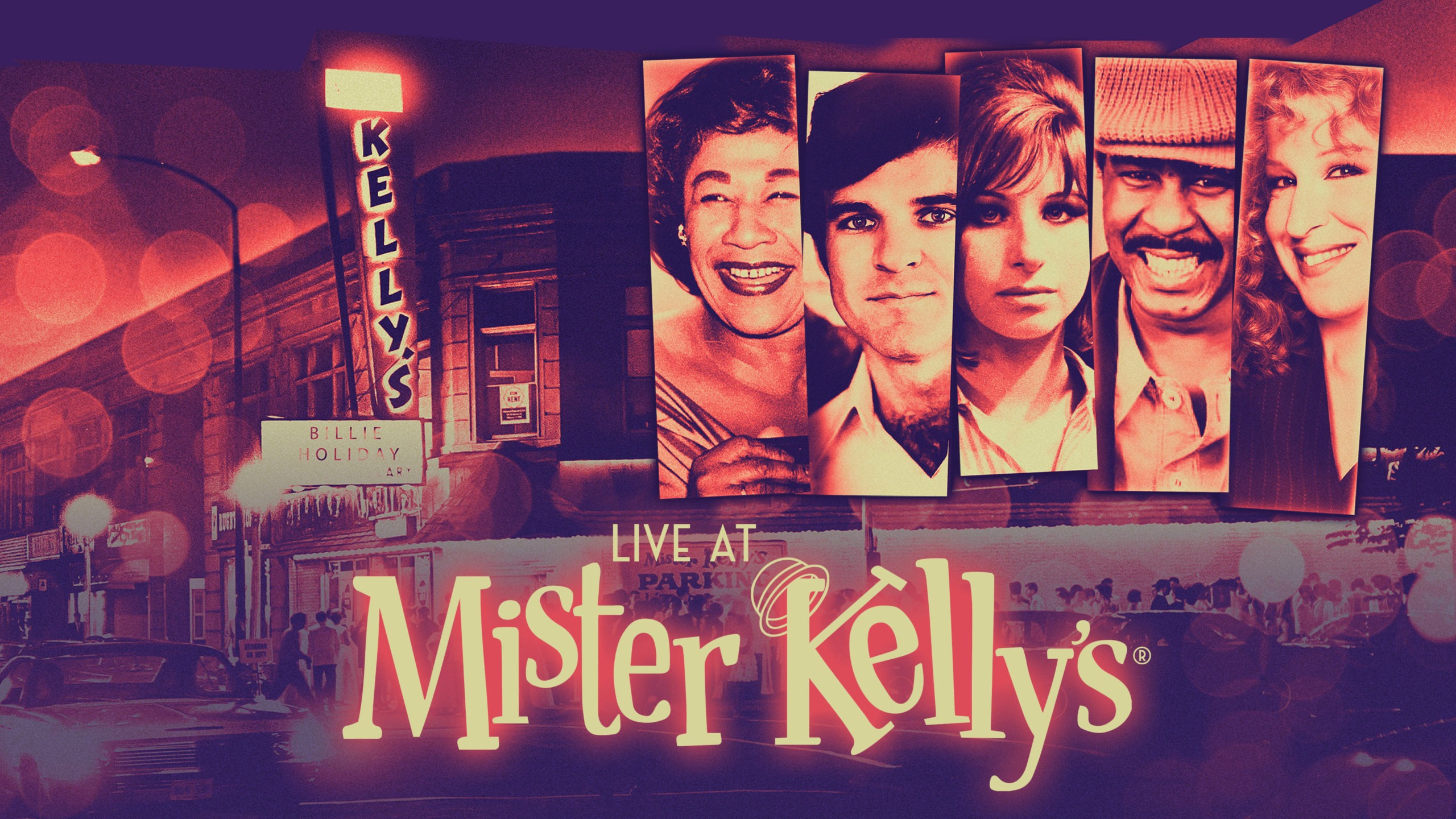

A new documentary, Live at Mister Kelly’s, available now on Video on Demand and next week on DVD, tries to recreate that scene for modern viewers, but doesn’t quite succeed in taking us back 60 years. The film is clearly a labor of love for everyone involved. Director Theodore Bogosian is a New York native who nonetheless “spent the 1960s listening to Chicago radio stations. At all hours of the day and night my AM radio pulled in music from the Windy City on WLS, WCFL, and Don McNeill’s Breakfast Club and I gravitated toward Kup’s Show and Playboy Magazine on television and — thrillingly — in print.” Executive Producer David Marienthal is the son of George Marienthal, who operated Mister Kelly’s along with his brother, Oscar.

Unfortunately, as narrator Bill Kurtis (who else?) tells us, “nearly all the motion pictures shot inside the club have disappeared.” Instead, we get talking head interviews with entertainers of a certain age reminiscing about when they were the biggest names in show business, and Mister Kelly’s was the biggest venue for their talents. If you ever went to Mister Kelly’s, the movie will be a pleasant, 83-minute return to your youth. If you didn’t, the movie won’t let you in on what you missed.

“To be a hit at Mister Kelly’s, that’s what it’s all about,” Bob Newhart says.

“If you were on the Ed Sullivan Show and did well, the next step was Mister Kelly’s,” Fred Willard says.

Barbra Streisand first played Mister Kelly’s in 1963, under a marquee with a one-word review — “Fantastick” — from a one-name reviewer — Kup. (That would be the Sun-Times’ Irv Kupcinet, whose heyday coincided with Mister Kelly’s.) The morning after the show, a photographer took a sunrise portrait of Streisand on Oak Street Beach, which became the Grammy-winning cover of her album People.

“I like to think Chicago has always brought me good luck,” Streisand says. “It really is a special town, Chicago. I think there’s a song about that, isn’t there?”

Streisand’s singing is timeless, but Live at Mister Kelly’s also has interviews with Shecky Greene, the pride of Sullivan High School, wearing a Cubs jacket labeled “Hitting Coach.” Mort Sahl can rightly claim to be the progenitor of Jon Stewart and Bill Maher, but here he’s cracking jokes about Adlai Stevenson and Nelson Rockefeller.

“I didn’t talk about my mother-in-law,” Sahl says. “I talked about politics and what was going on in the country.”

Mister Kelly’s was intertwined with the Playboy aesthetic — the club was just a few blocks from the Mansion — so we also get a clip of Hugh Hefner, still every inch the Steinmetz High School geek, trying to look sophisticated with a tuxedo and a pipe.

It’s hard to identify the moment when Mister Kelly’s went from hip to passe, but even the movie concedes that time passed it by. Richard Pryor performed the night Martin Luther King was assassinated — then disappeared for a year and returned with an angrier, more racially-conscious brand of comedy.

“The combination of changing tastes and competition from bigger venues topples their empire,” Bill Kurtis says of the Marienthals. The club closed in 1975, shortly after Jay L. No (as the marquee identified him) performed there. Nightclubs were replaced by stadium tours, which are now being replaced by streaming home entertainment.

“People don’t want to go anywhere,” Mister Kelly’s veteran David Steinberg kvetches. “They’ve got everything with them in their wallet, so it’s a little bit harder, but live performing, live showmanship, that will never go away.”

I’m sure Steinberg put on a great show at Mister Kelly’s. But you had to be there.