It was the final day of Black History Month and Stacy Davis Gates needed to be in three places at once.

The Chicago Teachers Union’s monthly executive board meeting was scheduled at the same time as its Jammin’ for PEACE celebration, which overlapped with a group of Nicholson STEM Academy teachers gathering virtually with their union delegate to talk pedagogy, burnout, and whatever else needed airing — a discussion Gates had promised to attend.

A few minutes past 6 p.m., with the board meeting streaming on her iPhone, Gates walked through the refurbished warehouse in West Town that serves as the union’s headquarters and into the Jacqueline B. Vaughn Hall, named for first African American woman to lead the CTU. Tara Stamps, a CTU administrator and daughter of the late community activist Marion Nzinga Stamps, was onstage introducing the Jammin’ for PEACE speakers and performers. The crowd of 50 or so strong stood for “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

Stamps turned her attention to Gates. “Whenever I see our sister, you know who I see?” Stamps called out. “I see 10, 20, 30, 45, 100 little brown girls that look just like her. So we got next. We got next because there’s a Stacy Gates.”

The air crackled with applause. Gates took the stage.

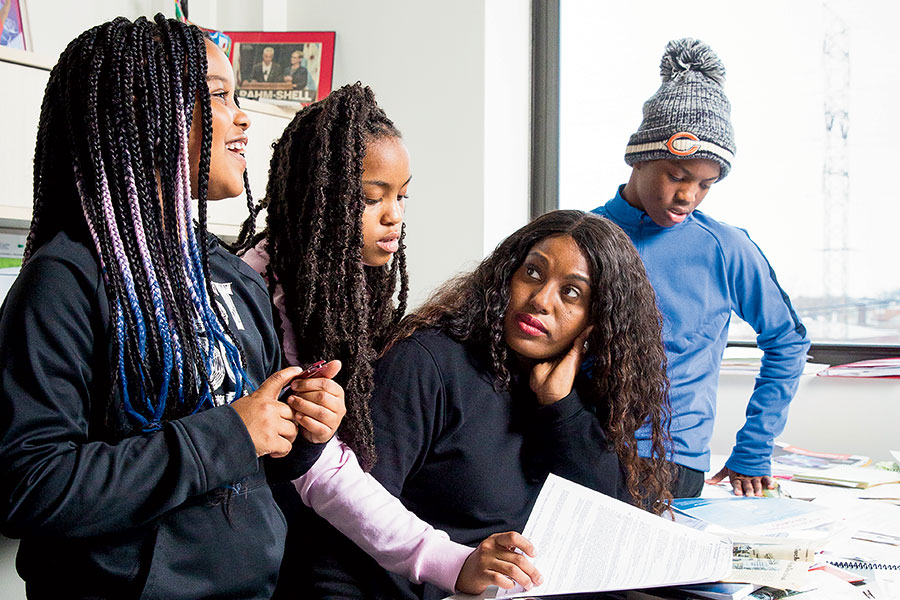

In Gates’s office at CTU headquarters, a “Notorious SDG” print with her likeness hangs above her desk — a riff on those “Notorious RBG” prints that were ubiquitous for a while. A union member made it for her.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m living my life as a spectator,” says Gates, the union’s vice president and heir apparent. “I’m not the caricature in the letters to the editor.” But caricatures are easier to digest — and dismiss — than the deficits and disinvestments plaguing public schools. “The problems are complex. They’re embedded in our American history. And I think because of that, it’s easier for people to extract characters and focus on them. Because focusing on the actual context and the thing? It depresses you. It makes you angry. And it also is paralyzing, because you’re trying to make sense out of nonsense.”

The public face of Chicago’s teachers, who stand squarely at the center of the country’s labor movement and culture wars, Gates, 45, is an unflinching critic of Mayor Lori Lightfoot and a fierce opponent of attempts to privatize public education. And now, after CTU president Jesse Sharkey announced in February that he wouldn’t seek reelection, she is primed to take over the top slot at what is arguably the nation’s most powerful teachers’ union.

Unless, that is, she is somehow beaten out in the May 20 election by a dissenting caucus of Chicago Public Schools employees called Members First. When the group first challenged the union’s current administration three years ago, Sharkey won reelection handily, with two-thirds of the vote. “I don’t intend to lose,” Gates tells me.

Gates is revered and resented in equal parts — or at least at equal volume. Her detractors blame her for contributing to a contentious relationship between the CTU and the mayor that resulted in an 11-school-day teachers’ strike in October 2019 — the longest in decades. That was followed by another five days of canceled classes after members voted to return to remote learning during this January’s omicron surge and the district responded by locking them out of their virtual classrooms.

Members First is running, in part, on the belief that the union needs to have a better relationship with city officials. “Stacy Davis Gates and her leadership team have put their interests ahead of our union’s members and the students we serve,” Mary Esposito-Usterbowski, the group’s presidential candidate and a citywide school psychologist, told me in an email response to my interview request. “She sees work stoppages and strikes as the first step and not the last one. Stacy’s relationship with the mayor and CPS CEO is toxic, and this will make it very difficult for her to deliver for us.”

Gates’s allies, though, credit her with helping transform the landscape at the city’s 636 public schools, which are on track to add a nurse and social worker to every building by 2024 — a hard-fought victory in the strike three years ago. “We don’t win half the things we achieved in 2019 without Stacy,” says Jackson Potter, the union’s former staff coordinator.

Animosity between the CTU and the mayor, who controls the city’s schools, often dominates the discourse around public education in Chicago. Neither side backs down from the fight. At a press conference shortly after the majority of CTU members voted in January to work remotely, Lightfoot accused the union of turning Chicago into “a laughingstock all across the country” and declared: “We will not pay you to abandon your posts and your children at a time when they and their families need us most. It will not happen on my watch.”

At her own news conference, Gates fired back, going after Lightfoot personally: “This mayor is unfit to lead our city. She’s on a one-woman kamikaze mission to destroy our public schools.” She also called Lightfoot “micromanaging” and a “bad boss” in an interview with the Chicago Sun-Times and told the New York Times: “She does not know how to play well with others.”

But beneath the tension — indeed, fueling the tension — is a fundamental disagreement over policy. “These aren’t just personality conflicts,” Sharkey tells me. “These are people who represent institutions, and the institutions have conflict, and the conflict is about how resources get spent and whose opinions get to count and how power and money are spent. This is not like a couple of angry Black women.”

There are those who assert — in letters to the editor, in editorials, in op-eds, on Twitter, from podiums — that the CTU’s fights actively harm children and families in Chicago. That the work stoppages rob students of crucial instructional time. That the public sparring and uncertainty send families fleeing for private schools or the suburbs. That working parents are needlessly burdened by late-night union votes and canceled classes.

Gates understands the frustration, particularly around strikes. But, she argues, historical wrongs aren’t quickly righted. “These are very difficult human conditions that we’re trying to make sense of,” she says. “The impact of historical, generational disinvestment on the South Side and West Side of the city is difficult for people who are experiencing it to challenge, because it’s every day and it covers all facets of their existence. And for those who are not experiencing that in the same way, it is difficult to even grasp why this is happening.”

Gates wanted to be Perry Mason when she grew up. “My pawpaw used to watch it, and I watched it with him,” she says. “It was simple: Someone did something wrong, there was an investigation and they always got the wrong guy, and Perry always got them off. I liked the ability to free someone from something that was unfair or unjust.”

A native of South Bend, Indiana, Gates carried her criminal defense lawyer dreams to St. Mary’s College, where she declared a major in English. (“I was told you have to be a good writer to be an attorney.”) She volunteered with an Urban League program that connected her to local middle school kids, and she felt pulled toward child advocacy.

“Then I started thinking that would put me on the wrong end of the spectrum of justice,” she says. “By the time I got to meet these kids, something would have already happened.” So she set her sights upstream: Grab them before they’re thrown into the water, to paraphrase Desmond Tutu, rather than standing downstream to keep pulling them out. But she would later learn that it wasn’t always so level upstream. “As a 19-year-old,” she says, “it wasn’t clear to me that injustices are already embedded into our school communities — larger societal deficits, disinvestments.”

After college, Gates moved to Chicago, a city that had beckoned and shaped her elders. Her paternal grandfather left Mississippi to work at a factory here, then left that job for one at a steel mill in Gary before eventually ending up at the Studebaker plant in South Bend, where he put down roots. Her maternal grandmother left Arkansas, worked on the West Side of Chicago, and wound her way to South Bend. “Both branches took the same path,” Gates says. “I was meant to be a Chicagoan.”

In 2004, she became one, landing a job as a history teacher at Englewood High School. “It was a tough year,” she says. “I didn’t know what I was doing. I remember spending a lot of time in preparation for classes — getting primary sources together, getting supporting documentation together, making connections through newspaper articles and periodicals that related back to the historical thing I was teaching. And there was always a segment of my class that was disconnected, that didn’t want to hear it or didn’t engage fully.”

The hallways of Englewood High were lined with photos of notable alums: Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior under Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman; Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American to be selected as an astronaut; Harold Bradley Sr., who was one of just 13 African American players in the National Football League before World War II; Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks. The auditorium was named for playwright Lorraine Hansberry, who graduated in 1947.

But the school, like the surrounding neighborhood, had been neglected by city leaders for decades. Enrollment had declined precipitously. The running track was barely usable, with dangerous dips in its lanes. “I remember we were never able to take a book home because they didn’t have a book for every student,” says Latoyia Kimbrough, a 2005 graduate who now works as in-house legal counsel for CTU.

By her second semester of teaching, Gates started looking for ways to make inroads with her students that had little to do with curriculum. She played in student-staff basketball games. She showed up to cheer on the football team on Friday nights. She chaperoned the prom. “My credibility came slowly, and it had nothing to do with my instruction or my understanding of content,” she says. “It had to do with finding human connections.”

Kimbrough was in Gates’s first African American history class. “Students would try you a lot,” Kimbrough says. “And they tried her a lot because she was younger. But she didn’t play any games. She shut that down pretty quickly.”

Kimbrough remembers Gates and Potter, Englewood High’s debate coach at the time, playing in those basketball games. “After that we looked out for them,” she says. “It was like a family. They were a constant in a time when things were just all over the place. It was more than, ‘I care about what I’m teaching you.’ It was, ‘I care about you personally.’ ”

Then, in Gates’s second year at Englewood High, CPS announced the school would close after that year’s freshman class graduated. She remembers Arne Duncan, CPS’s CEO at the time, delivering the news at her building. “I was hurt. I was angry. It made me feel powerless. It made me feel like a failure,” says Gates. “That was the moment I was radicalized.”

She and her students attended the community meetings that were part of the school-closing process. But they had an air of choreography, she says, of an outcome predetermined before anyone even spoke. She imagined her students’ voices landing on the ears of the decision makers the way Charlie Brown’s teacher’s words sounded to the Peanuts classroom.

“It felt familiar,” she says, “especially because I was teaching African American history that year. It felt like people were still begging American institutions to see our humanity. It felt demoralizing. It felt like the humanity was removed from us. It felt like we were set up to take this fall because there were few investments, few supports, and timetables for achievement that they knew we couldn’t meet. It turned me upside down.”

In 2005, in Gates’s second year teaching at Englewood High, CPS announced the school would close. “I was hurt. I was angry. It made me feel powerless. That was the moment I was radicalized.”

When the school closed in 2008, Gates moved to Roberto Clemente Community Academy in Ukrainian Village, a high school that had been tasked with absorbing students reassigned from Austin Community Academy High School, which was shuttered in 2007. She says there were fights every day on the corner of Western and Division. The school went through three principals her first year.

Chicago has closed or “radically shaken up” some 200 public schools, or a third of the district, since 2002, according to a WBEZ investigation. Closures as a reform measure became an option in 1995, when Mayor Richard M. Daley gained control of the city’s schools under a new state law. They are a measure that Duncan, who went on to become U.S. education secretary, exercised frequently during his eight-year stint as CEO and that Rahm Emanuel put to use as mayor.

“It really makes you understand how the city works and who the city works for and who the city doesn’t,” says Dave Stieber, a social studies and poetry teacher at Kenwood Academy High School and a vocal CTU supporter on social media. Stieber began his career at TEAM Englewood Academy, a public high school that, along with an Urban Prep Academies charter school, took over the building that once housed Englewood High School. Three years ago, TEAM Englewood closed as well. “You’d see these kids going to school-closing hearings, singing, performing, saying, ‘Please don’t close our school. We’ve got this amazing band program.’ And they’d close it anyway. It does something to you.”

As Englewood High School was closing, the CTU was undergoing a radical transformation, led largely by Potter, away from a pay-and-benefits focus and toward a citizen activist approach. “From milquetoast to militant” is how Jane F. McAlevey described the union’s evolution in her 2016 book, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age. “If the labor movement’s instinct has been to reduce demands in order to sound reasonable, the new CTU took the opposite approach,” McAlevey wrote. “They led every meeting with school-based discussions of billionaires, banks and racism.”

The union started partnering with community organizations known largely for fighting gentrification — the Pilsen Alliance, Logan Square Neighborhood Alliance, Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization — to attend school board meetings and host community forums on school closures. “There was a movement afoot to say our union has to be more than a place that bargains a contract for a finite amount of time,” Gates says. “Our union couldn’t be silent on what was happening to the children in the city, the families in the city.”

Karen Lewis, a longtime chemistry teacher, was elected to lead the newly reform-minded CTU in 2010. Widely popular with its more than 25,000 members, she was considering a run for mayor when she was diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer, in 2014. Four years later, after undergoing brain surgery, she retired, and Sharkey, her vice president, took over. (Lewis died in 2021.) Gates — who had stepped away from the classroom in 2011 to ramp up her union activities, traveling to Springfield to lobby for the CTU’s legislative agenda and serving as the organization’s political director — was elected to fill his post.

The 2019 teachers’ strike, which took place five months into Lightfoot’s term, captured national attention for both its length and the groundbreaking issues it brought to the bargaining table. The union made a push for affordable housing for students and teachers to be written into their contract, along with sanctuary protection for immigrants — unprecedented demands.

It irks Gates that there’s an expectation that she and the mayor should get along. “I’m disappointed that in 2022 we still believe that Black people are a monolith.”

Neither issue stuck, but the negotiations forced the two sides — and everyone watching them — to grapple with how learning and achieving are affected by far more than class size and pedagogy. A 2021 study by the University of Chicago’s Inclusive Economy Lab found that one in seven CPS students experiences homelessness.

Some notable people were looking on. Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, traveled to Chicago to lend her support. Elizabeth Warren, a presidential candidate at the time, joined teachers on the picket line on a blustery October morning. Bernie Sanders, also vying for the presidential nomination, attended a CTU rally before the strike. “Every problem in society — hunger, domestic violence, poverty — it walks into your doors, doesn’t it?” Sanders said to the crowd gathered inside CTU headquarters.

By the time teachers and students returned to classrooms in November 2019 — four months before COVID-19 would force schools to close again — the union had successfully bargained for a social worker, nurse, and librarian in every school, $35 million in spending to reduce overcrowded classrooms, a 16 percent pay raise for teachers over five years, and a 40 percent pay raise for teaching assistants, clerks, and other historically underpaid support staff members.

Teachers’ strikes are not new to this city. From 1969 to 1987, CTU staged nine walkouts, according to the Chicago Tribune. A 1987 strike lasted a record 19 school days. In 2012, teachers went on strike for seven days. Discord between CTU leadership and the mayor is hardly novel, either. Lewis feuded with Emanuel, dubbing him “the murder mayor” and “Mayor 1 Percent.” Emanuel, for his part, famously barked “Fuck you, Lewis” during a private meeting in 2011. (That didn’t rattle Lewis, who years later told a crowd gathered at the Hideout for an event, “I know bad words, too. I can take off my earrings and get the Vaseline.”)

Still, the nationally televised conflict early in Lightfoot’s term — with Democratic heavy hitters siding with the teachers — set the stage for the successive years of highly tempestuous dealings. But that doesn’t faze Gates. In fact, it irks her that there’s an expectation that she and Lightfoot should get along because they’re both Black women. She takes issue with a January column in the Chicago Sun-Times by Rebecca Sive, a women’s leadership strategist, calling on the two to smooth things over. “I have enormous respect for the load Lightfoot and Gates carry,” Sive wrote, “but we’re tired, girlfriends. Really tired. And also really scared. Please settle up and move on.”

Says Gates: “I’m disappointed that in 2022 we still believe that Black people are a monolith and one-dimensional. It is also terrible there is an assumption that women get along even if they disagree.” (In response to a request for an interview, Lightfoot sent an email that said, in part: “I am willing to work with all stakeholders who come to the table in good faith and who always put our kids and their families first.”)

“Folks are concentrating on red lipstick,” Gates continues, referencing her signature look, “or the back-and-forth. And they’re not paying attention to a Chicago where you have two Black women who have leadership and influence who think differently. I think that’s an achievement, that we are all free to have differing thought processes on anything, and that women have voice in a city as dynamic as Chicago. People are missing that part of it.”

“We don’t have infrastructure in our public schools to deal with the impact of the traumas our youths walk into our schools with. You are confronted with unparalleled grief.”

“Stacy’s brilliant,” Sharkey says. “She’s also extremely sensitive. So not only does she really have a lot of head for strategy and thinking about politics, but she also tracks a tremendous amount of things, in both a good and a bad way.” That’s one reason negotiations have been fractious with the mayor’s team. “There are lots of ways in which they don’t really want to be there,” Sharkey says. “And if you show up and you’re not serious, Stacy will get that within two seconds of being in a room. If someone mistreats her, she notices. And she doesn’t like it.”

He calls her sensitivity her “superpower,” even as it invites blowback. “She has very fine antennae and a finely honed sense of justice about what’s right and fair,” Sharkey says. “And someone with those qualities — sensitive, brilliant, cares a lot about justice — if you’re a Black woman with those qualities, you get a lot of people who take umbrage.”

He recalls a story that Gates told him years ago about being the only Black girl in the gifted program at her South Bend elementary school. The gifted students were invited on a field trip to Philadelphia to see the Liberty Bell and other historic landmarks. “Stacy says, ‘What about the rest of the kids?’ ” Sharkey recounts. “And they’re like, ‘No, it’s just for the honor kids.’ And she’s like, ‘Well, then I ain’t going.’ I mean, imagine being that kid in third grade or fifth grade who’s like, ‘No. I’m not going on your field trip because it’s not fair.’ ”

She was actually in sixth grade, Gates later clarifies. And she did go on the trip. “I was made to,” she says, “by my parents.” They weren’t about to let her miss the Liberty Bell — or disobey the principal. But it was an early taste, she says, of airing a grievance, of pushing back on behalf of those who aren’t in the room. And it was an early glimpse at the way some kids are placed on a path to succeed, while others are left behind. Even as a sixth grader, it bugged her — just as the injustice and tragedy she sees now motivate her.

Chicago is a city that can leave behind, even devour, its young. Last year, 415 children were shot here. This year began with the shooting death of 8-year-old Melissa Ortega, a student at Emiliano Zapata Academy in Little Village; the murder of Amanda Alvarez-Calo, a pre-K teacher at Matthew Gallistel Language Academy in East Side; and a shooting outside Alessandro Volta Elementary School in Albany Park that sent it into lockdown.

“We don’t have infrastructure in our public schools to deal with the impact of the traumas our youths walk into our schools with,” Gates says. “You are confronted with unparalleled grief. You are confronted with different children from different households coming inside a school community who are processing rape and violence and trauma in so many different ways. And the classroom teacher is tasked with making sense of it. It’s a high bar. And the students need you to clear it — like they need their next breath, they need you to clear it.”

The ongoing pandemic has disproportionately affected Chicago’s Black and brown residents, who make up close to 90 percent of CPS families. Students have lost parents, grandparents, and caregivers. So have their teachers. In January, shortly after teachers and students returned to their classrooms, students staged a massive walkout to protest a lack of safety mitigations during a record-setting surge of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations.

“Why are we negotiating safety?” Gates asks. “We sat at a table debating ventilation during an airborne pandemic. Or, ‘Omicron’s peaking. It seems pretty dangerous. We know how to teach remotely. We may not like it, but it just makes sense right now.’ The fact that you have to fight for these things, it feels like punishment.” But she has no choice, she says. “If you don’t fight for it, you won’t receive it.”

Gates and her husband, Kevin, have three children — in second, fifth, and seventh grades. They attend a public school on the South Side. The couple’s son is named after his father. Their daughters, Laura and Hazel, are named after Gates’s grandmothers, both of whom picked cotton to earn money. “I tell people all the time I’m only one generation separated from a cotton field,” Gates says.

Her dad was the first child in his family to be born in the North. Her mother was born in the South and left during the Great Migration. “I think about them often in this work,” she says. “I think about the lessons I got as a kid: You have to be twice as good to get half as much. When you work on a team, when you’re doing coalition work, it’s important for your team to understand the dynamics of gender and race because those things do impact the institution you lead as well. I feel real accountable for unpacking that. Not just for the team of people I work with every day, but also for the members.”

She tries to imagine her grandmothers, as girls, imagining her. “My granny was a teenage mother — a teenage single mother with an alcoholic father who was a sharecropper. My other grandmother was born out of wedlock and ostracized from both sides of her family tree. Yet both of these women overcame so much to put their children in a position — to put me in a position — to succeed. And in this moment I really and truly feel accountable for their sacrifice. I feel privileged to be in this space that they struggled to dream of, against every imaginable odd.”

Grandmother Laura passed away when Gates was in college. Grandmother Hazel died a week before her namesake was born. Yet they remain a part of Gates. “When you hear my fire, you hear Hazel. When my members hear how much I love them, they hear Laura.”

She’s loath to squander the opportunities they provided her. “I think that’s why I go so hard, why I’m so clear about my leadership. They were so fearless in their ability to dream of me in this moment. I’m going to continue to embody both of their hopes and dreams, but also provide a pathway for the Hazel and the Laura in my household right now, that they get to be whoever they want to be in this world.” Later she tells me: “I can’t advocate on behalf of public education and the children of this city and educators in this city without it taking root in my own household.”

Change is a constant for Chicago schools. CPS has had four CEOs in the past seven years, including two — Barbara Byrd-Bennett and Forrest Claypool — who left in disgrace. (Current CEO Pedro Martinez, in office since September, didn’t respond to requests for an interview for this story.) More change is coming in May, when the CTU selects its next leader.

“It was a lot of things,” Sharkey says about not seeking reelection. “It is definitely the case that my decision was because I was confident in the quality of our leadership and our movement broadly. I think Stacy is a remarkably effective public spokesperson. I can think of no one I’d personally like to run the union more, but that’s a decision our members get to make.”

Sharkey, 52, has been floated as a possible mayoral candidate. He hasn’t publicly ruled it out, but he says his current plan is to return to the classroom. Before Sharkey’s announcement, Gates’s name also had been brought up as a possible contender. (When asked about it on the Crain’s Chicago Business podcast A.D. Q&A in January, Gates said that the notion of her running was something she first heard from Lightfoot’s lips and was “not a priority” for her.)

“My counsel to her is ‘One thing at a time,’ ” Sharkey says. “The CTU is no small thing. We felt like the system was being sabotaged by the people who were in charge of it, and the union was the one institution that had both the interest and the ability to do something about that. This is an organization that historically has represented an awful lot of important stuff in the aspirations of working-class Chicagoans in general, but Black working-class Chicagoans especially. They are sort of the bedrock constituency of our public schools.”

Gates tells me she is focused on May 20 — on winning the top CTU spot and following in the footsteps of Lewis, her friend and role model, who shaped her management style. “Karen was a curious leader,” Gates says. “One of the first things she would say to you was ‘What don’t I know? What am I missing?’ I’ve adopted the same two questions. She made it OK to be powerful, curious, and vulnerable all at the same time.”

As for politics, Gates says she’s not sure she’s cut out for it. Maybe not, but she can deliver one hell of a speech.

“This whole country said at one point, post–George Floyd, that Black lives matter,” she called out from the Jacqueline B. Vaughn Hall stage on that final night of February. “And we have been searching for that matter for centuries. Don’t be discouraged in the moment of great need. Don’t be compelled to turn around and walk backwards in the time of need. We see our schools closed and defunded. We see the surveillance and pain in our neighborhoods. They take away the things we need the most in order to survive. I ain’t said live yet. I said survive. So we have to be astute historians and know that our voice is necessary to this moment. Our courage, our organizing, our value are necessary in this moment.”

Shouts of “Talk, Stacy!” filled the room.

“They would have you to believe that you can’t read Beloved in a classroom,” she continued. “They would have you to believe that Black lives, queer lives don’t matter in this country. So I want to say this: We are fighters at this union. We don’t walk backwards and pretend that yesterday was better than what we can imagine tomorrow to be. We are in love with humanity at this union.

“So I want you to stay encouraged, Chicago Teachers Union. I need you to stay in love with the children in this school district. I need you to be even more in love with equity and justice. And I need you to see love as the essential tool to continue to transform this city, this state, this nation, and this world. Continue to pray for Ukraine. I love you.”

She walked off the stage and headed upstairs to join the Nicholson STEM Academy teachers’ meeting. On the elevator, I asked her if her speech was prepared. She didn’t have any notes with her onstage.

“That’s my family,” she said. “You don’t need notes to talk to your family.”