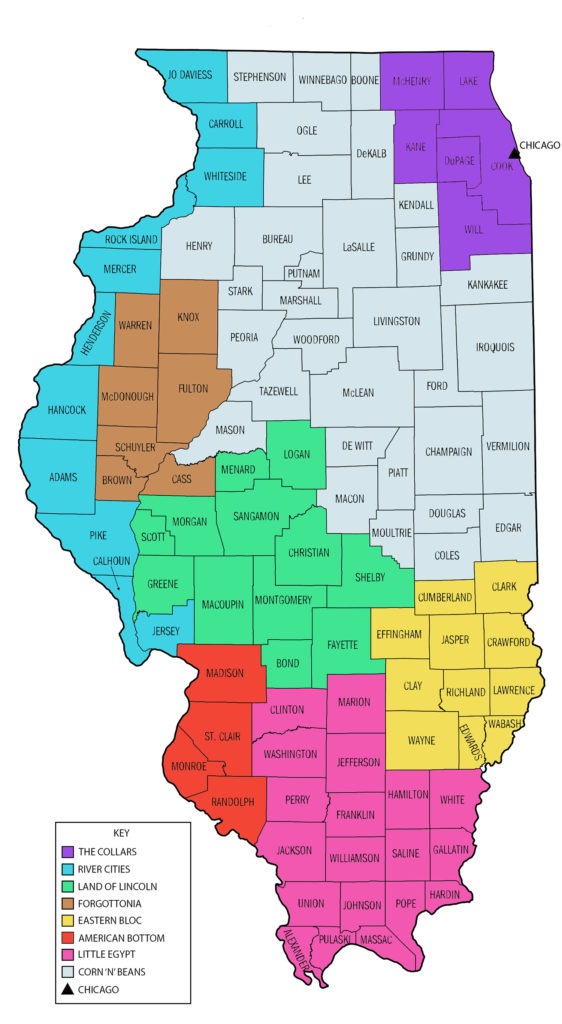

Illinois has a new $30 million tourism campaign: “The Middle of Everything,” with a series of TV ads narrated by Dolton’s own Jane Lynch. What, exactly, do Americans think of when they think of Illinois? What do Illinoisans think of when they think of Illinois? Illinois is distinct among states for not being distinct. We don’t have a strong, unifying identity, like our neighbors Wisconsin (cheese), Iowa (corn), and Kentucky (horse racing and bourbon). Part of that is because our 450-mile length cuts across three cultural regions: the North, the Midlands and the South. Part of it is the deep urban-small town divide, between Chicago and Downstate. As we see it, Illinois is actually nine sub-states, all coexisting under the same boring flag.

Chicago

Illinois’s largest city feels very little connection or identification with the state it dominates politically, culturally and economically — much to the annoyance of Downstate. “I’m not an Illinoisan,” a friend once told me; “I’m a Chicagoan. I kick ass and eat Italian beefs.” Chicagoans don’t summer in Illinois; they summer in Wisconsin and Michigan, with which the city shares a Great Lake. Chicagoans have always thought of Downstate — when they’ve thought of it at all — as an irrelevant agricultural appendage full of Baptists and gun owners who’d just love to turn Illinois into West Indiana. A city with a regional, national, even global outlook, Chicago doesn’t have time for Decatur or Peoria — except to steal their corporate headquarters. In recent years, ADM moved its executives from Decatur to Chicago, while Caterpillar’s moved from Peoria to Deerfield. Telling those cities “the jobs didn’t leave Illinois” is no consolation.

The Collar Counties

The suburbs once defined themselves in opposition to Chicago, populated as they were by World War II veterans who fled the city to escape its crime and corruption. Illinois politics was once marked by the competition between Democratic Chicago and Republican suburbia. In six successive elections, from 1968 to 1988, Illinois voted Republican for president. The young people moving to suburbia today aren’t much different from their 1950s forebears: professionals, buying their first houses, starting families. Politically, though, they couldn’t have less in common with the gruff conservatives: most are pro-choice, pro-gun control, and pro-government, willing to tax themselves for schools and libraries. Since the early 1990s, when Bill Clinton became the first Democrat since LBJ to win Illinois, the political line between city and suburb has been erased, and the state has become reliably Democratic. Chicago’s suburbs have come to define suburbia for the entire nation, through movies such as Risky Business, National Lampoon’s Vacation and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and books such as The Nix and Crossroads.

River Cities

Illinois is the Mississippiest state in the union. We have more Mississippi River on our border than anyone: 575 miles from East Dubuque to Cairo. Illinois is a “heavy maritime state,” says Tom Horgan, senior manager of the American Waterways Organization Mid-Continent Office in St. Louis, an agency that advocates for the tugboat and barge industry. Barges ferry a significant portion of the state’s corn and soybean crop up and down the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. During the fall harvest season, 12 to 15 trains pass every day through Lock 15, alongside Arsenal Island, home of the Rock Island Arsenal, a U.S. Army facility that dates back to the Civil War. Barge operators like to boast that theirs is the most cost-effective and environmentally friendly form of transportation. A single barge can hold 62,492 bushels of corn — as much as 16 rail cars or 70 tractor trailers. The river cities are not as prosperous as they were when the Mississippi was the nation’s most important commercial thoroughfare, but legacies of wealth remain. Quincy has four historic districts, containing examples of just about every architectural style popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Queen Anne, Romanesque, Italianate, Second Empire, even Moorish.

Corn ‘n’ Bean Country

Illinois is second in the nation in corn production, after Iowa. We’re number one in soybeans, ahead of Iowa. The counties that grew the most corn last year are McLean, with 64 million bushels, and Iroquois, with 60 million. Decatur calls itself “The Soybean Capital of the World,” processing the crop at Archer Daniels Midland and Staley plants that scent the city’s air with an aroma known as “the smell of money,” because of the jobs the companies provide. (Decatur so identifies with the bean that its largest radio station bears the call letters WSOY.) “Walking beans” — weeding a beanfield — was a popular summer job for teenagers before the development of modern pesticides. When Illinois’s first settlers plowed up the prairie, they found some of the best farmland in the world underneath. As the soybean state, Illinois is trying to take advantage of shifting tastes toward meatless meals. Harold Wilken, a soybean farmer in Iroquois County, transformed his 2,200-acre farm into an organic operation. Rather than growing soybeans for animal feed, Wilken began supplying beans for soy milk and miso soup, and to Edgewater tofu maker Phoenix Bean. “Illinois is the ideal place to develop this industry,” says Vijay Singh, director of the University of Illinois Integrated Bioprocessing Research Laboratory. “We have some of the most fertile ground in the world.”

Land of Lincoln

“No other city in the United States, with the possible exception of Washington, D.C., is such a tribute in itself to a national hero,” the WPA Guide to Illinois wrote of Springfield. Without Lincoln, Springfield would be just another obscure Midwestern state capital, like Des Moines or Topeka. As the hometown of America’s most revered, most written-about president, it’s a tourist attraction. The Abraham Lincoln Museum receives more than 300,000 visitors a year, nearly three times the city’s population. Daniel Day-Lewis stopped by while researching his Oscar-winning role. As the holy land of Lincolniana, Central Illinois is covered with worship sites. New Salem has been restored to resemble the 1830s settlement where Lincoln ran a store, studied law, and first ran for the legislature. Vandalia’s State House was only the capitol for three years, from 1836 to 1839, but it’s been preserved because Lincoln legislated there. Lincoln’s first Illinois home, along the Sangamon River between Decatur and Springfield, is a state historic site. So is his father’s farm in Coles County, even though Lincoln didn’t like farming — or his father.

American Bottom

Also known as Metro East, the American Bottom encompasses the trans-Mississippi suburbs of St. Louis: Alton, Edwardsville, Granite City, East St. Louis, all the way down to Kaskaskia, the first state capital, which is now on the west bank of the Mississippi, as a result of the river’s shifting course, but still part of Illinois. The fertile alluvial floodplain got its name after the War of Independence, when Americans began settling there and wanted to distinguish themselves from the Spanish across the river. Even before that, it was the site of Cahokia, the most advanced pre-Columbian civilization in what is now the U.S., peaking at a population of 20,000 in the thirteenth century. The Cahokians were mound builders, and their mounds still stand: from the top of Monks Mound, a visitor can see St. Louis. Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis was born in Alton. The city honors him with a statue, and calls itself “The Birthplace of Cool.” Alton also has a statue of the world’s tallest man, 8-foot-11-inch Robert Wadlow, but not of anti-Equal Rights Amendment activist Phyllis Schlafly, subject of the recent miniseries Mrs. America.

The Eastern Bloc

Southeastern Illinois is the most conservative corner of the state. How conservative? In the 2004 U.S. Senate election, a cluster of eight counties near the Wabash River voted for Alan Keyes over Barack Obama. The legislators from this part of the state are known as the “Eastern Bloc.” Their leader, state Sen. Darren Bailey, R-Xenia, was kicked out of the Capitol for refusing to wear a mask. Bailey is now a candidate for governor. Effingham and Teutopolis were settled by German Catholics migrating west on the old National Road, which has been replaced by Interstate 70. The nation’s second-tallest cross, 198 feet high, stands at the junction of I-70 and I-57. Olney is world famous as the home of a colony of albino squirrels.

Little Egypt

Deep Southern Illinois has long been nicknamed Egypt. The book Legends and Lore of Southern Illinois claims the region got its name after a hard frost in 1831 forced northern Illinois farmers to travel south to buy feed for their livestock. Like the sons of Jacob in the Bible, they were said to be “going down to Egypt for corn.” Other theories say it’s because the land around the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers resembles the Nile Delta. Southern Illinois University’s student newspaper is the Daily Egyptian. Its sports teams are the Salukis, after an Egyptian dog. This is the state’s coal country, celebrated annually at West Frankfort’s Old King Coal Festival. Illinois produced 36 million tons of coal in 2020, but the number of miners has dropped from 50,000 in the 1930s to 4,000 today, due to automated longwall mining. The United Mine Workers once made this a Democratic stronghold, but it’s now Trump Country, like the rest of the Upland South, from which it was settled. This is the hilliest section of our mostly flat state: the Shawnee National Forest and the Garden of the Gods are in the Illinois Ozarks. At the very bottom of the state, 400 miles from Chicago, is Cairo (pronounced KAY-ro), a nearly empty city whose population has shrunk over the last century from 15,203 to 1,733.

Forgottonia

In the late 1960s, western Illinois named itself “Forgottonia” for its lack of transportation infrastructure, after Congress defeated three proposals for a highway from Chicago to Kansas City. Let’s not forget them now.

Related Content