Bruce Rauner hated unions. But as a Republican governor with a Democratic legislature, he knew he couldn’t push through a statewide “right-to-work” law. Such legislation would have allowed employees in unionized workplaces to opt out of joining the union, costing it dues and bargaining power. So he attempted an end run: He proposed that local governments create such ordinances instead. Only Lincolnshire, a northwest suburb rich in corporate headquarters, took him up on it. But a federal court struck down its ordinance in 2018, and the next year, Rauner’s successor, J.B. Pritzker, signed a law preventing other local governments from attempting the same thing.

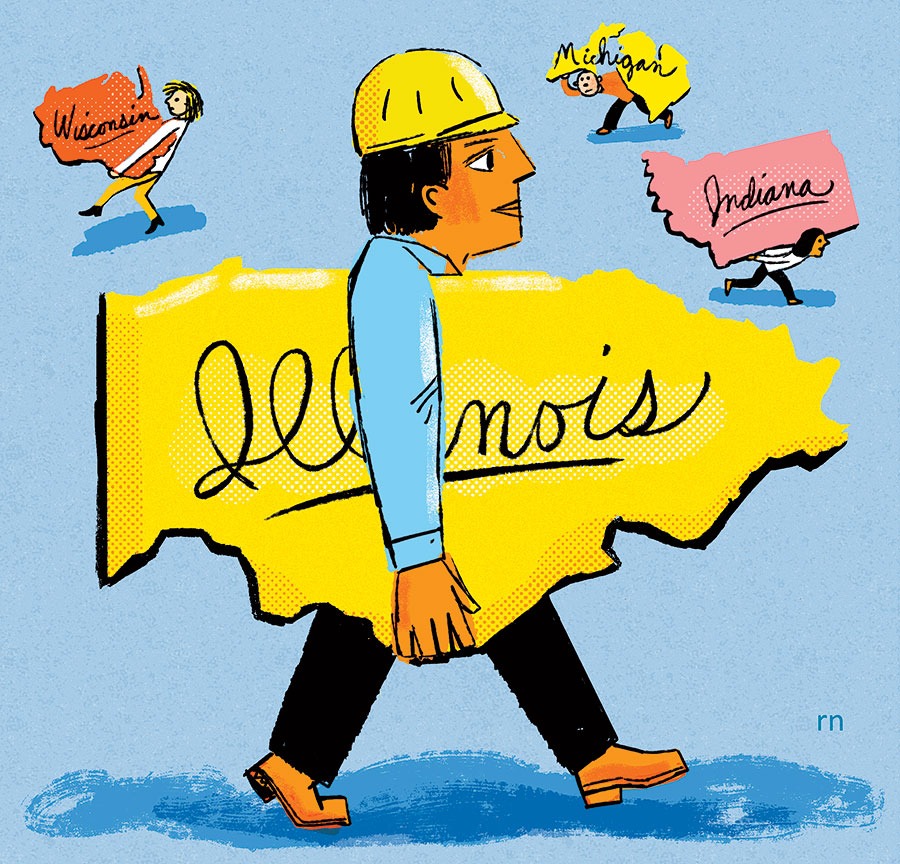

Still, Rauner’s anti-union attempt put a scare into labor and its legislative allies. They have collaborated to place an amendment to the Illinois Constitution on this November’s ballot that would make collective bargaining a “fundamental right” in the state, and prohibit the passage of any right-to-work law here. Much as Illinois has doubled down on abortion rights legislation while our neighbors have restricted abortion, the Workers’ Rights Amendment, appearing on the ballot as Amendment 1, would solidify our status as a prolabor island, surrounded by states that have been steadily dismantling union rights. In the last decade, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin all became right-to-work states. (Missouri’s legislature also passed such a law, but it was overturned by voters in 2018.)

“Bruce Rauner had a war on unions,” says Tim Drea, president of the Illinois AFL-CIO. “It was quite the wake-up call. We had also seen in Wisconsin, a progressive state that led the nation in labor, Scott Walker wiped out collective bargaining for public employees.” That was in 2011, and Wisconsin’s governor was able to do so because, unlike private sector workers, public sector employees are not protected by the National Labor Relations Act. Enshrining the right to collective bargaining in the state constitution would prevent an Illinois governor from following Walker’s example.

State senator Ram Villivalam, a Democrat from Chicago, sponsored the amendment to provide, he says, “stability and certainty” to workers after Rauner’s attempts to undermine their power. Illinois becoming a right-to-work state “is not a hypothetical scenario,” Villivalam continues. “This policy was [pushed] by the previous governor. Future politicians can be different than the ones we have today. We would rather have this voted on by voters than have politicians in Springfield changing the law every four years.”

Rauner was trying to ride an anti-union wave in the 2010s. The proponents of the Workers’ Rights Amendment hope they’ll be carried to victory by the pro-union wave of the 2020s. Since the COVID pandemic started, local union organizing drives have increased, most notably at coffee shops Starbucks and Intelligentsia, but also among nurses at Rush University Medical Center and service workers at Northwestern University. The risk of COVID made front-line workers more aggressive about negotiating safety precautions, and it made the public more sympathetic to their efforts to unionize. According to a recent Gallup poll, 71 percent of Americans approve of labor unions, the highest level since 1965.

Vote Yes for Workers’ Rights, a PAC formed by the Illinois AFL-CIO to promote the amendment, has raised more than $12 million, including $1 million apiece from LiUNA Chicago Laborers’ District Council and the International Union of Operating Engineers. The PAC has spent $4 million of that on a TV ad featuring a nurse complaining that staffing shortages and longer shifts at his hospital are endangering patients. “When we speak up, we risk being fired,” he says. “But the Workers’ Rights Amendment will protect us when we stand up for our patients.”

Will it, though? The Liberty Justice Center doesn’t think so. The right-leaning legal group filed a lawsuit to have the amendment removed from the ballot, arguing that only the federal government can regulate collective bargaining rights for private sector workers. That case, brought on behalf of Chicago Public Schools teachers and parents unhappy with how the teachers’ union negotiated its last contract, was thrown out by both state and federal courts.

The center’s president, Jacob Huebert, considers the amendment a Trojan horse for expanding the power of public sector unions: “They’re smuggling this in under something that might be more popular. It says, ‘We’re going to give rights to all employees,’ when really the state can only give them to public sector employees. A private sector employee might say, ‘More rights for me; I’ll vote for that.’ It’s hard to see this as anything other than deliberately deceptive.”

Huebert especially objects to language allowing workers to bargain “to protect their economic welfare,” fearing it could enable them to negotiate over issues that have nothing to do with wages or working conditions. “In Chicago, the teachers’ union is trying to bargain over things like affordable housing,” he says.

If, as Huebert asserts, the real beneficiaries of the amendment are public sector workers, it would protect only their collective bargaining rights. It would not override the U.S. Supreme Court’s Janus v. AFSCME decision. In that case, filed on behalf of an Illinois state employee, the court ruled that public sector unions cannot force their members to pay dues.

In fact, say nonpartisan experts, the amendment would do little to increase the rights of unions. What it would do, though, is protect those rights against future attacks, like the one brought by Rauner. “It’s primarily the protections of rights that workers currently have,” says Frank Manzo IV, executive director of the Illinois Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit research organization.

The amendment also sends a clear message about this state’s progressiveness when it comes to labor. If it passes, Illinois will become just the fourth state to protect collective bargaining in its constitution, along with New York, Hawaii, and Missouri. That doesn’t sit well with business boosters. Todd Maisch, president and CEO of the Illinois Chamber of Commerce, believes the amendment will hurt the state’s ability to bring new employers here. “I think it’s mostly another signal to the rest of the nation that Illinois is an outlier,” Maisch says. “We continue to find ways to make this state unattractive to investment.”

Perhaps. But it will make the state more attractive to workers.