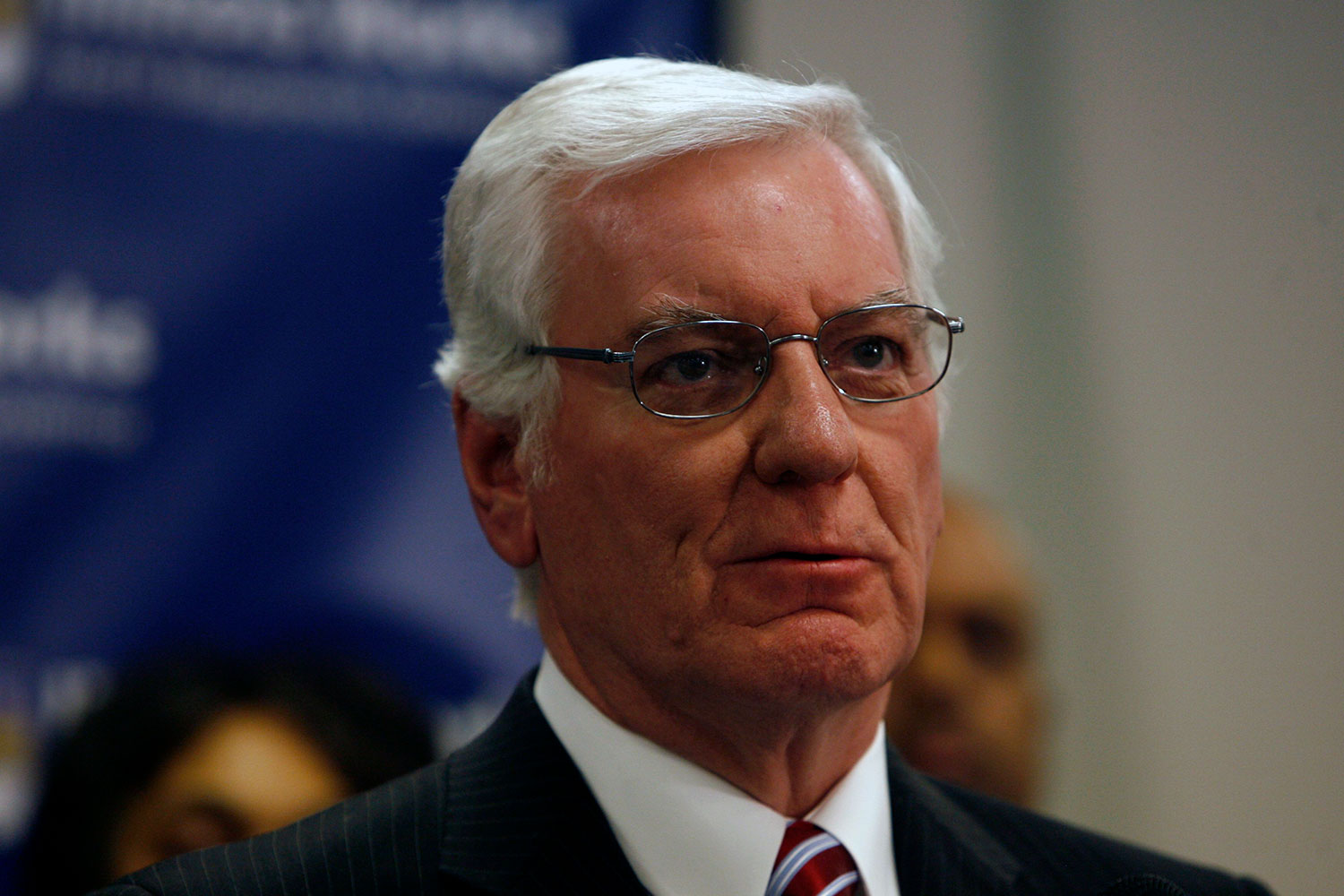

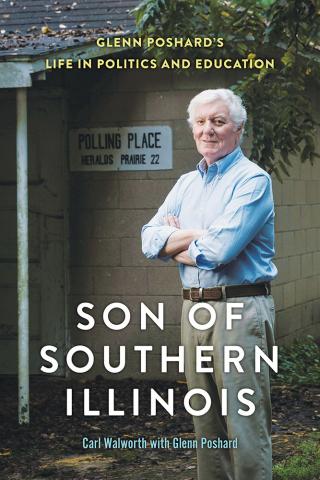

Glenn Poshard is one of the great “what ifs” of Illinois politics. If Poshard had won his race for governor in 1998, the state would have been spared the leadership — and the prison terms — of George Ryan and Rod Blagojevich. (“I wouldn’t have gone to jail,” Poshard once said.) As Poshard relates in his new memoir Son of Southern Illinois, written with journalist Carl Walworth, he lost that race because he was pro-life on abortion — not a position a Democratic nominee for governor would take today. Poshard swept his native Southern Illinois, but lost the collar counties, and even some socially progressive lakefront wards in Chicago — not an electoral map a Democratic candidate for governor would produce today. We talked to Poshard about the politics of abortion, and what the Democrats can do to win back Southern Illinois.

In the book, you talk about growing up poor, without running water, electricity, or plumbing. Your father had to take food relief. How did the economic circumstances of Southern Illinois influence the region’s political attitudes when you were growing up in the 1950s?

The political attitudes were strongly Democrat where I grew up and that was because the area was beginning to benefit from the Roosevelt Administration programs: the WPA, the CCC camps, rural electrification had begun to come to the hill country where I grew up. It was southern White County, which is a very hilly section of that county. We were known as hill people. People would refer to us, they’d say, “Yep, he’s from the hills.” A poor area. Red clay, not not much there, except there was a major oil find in the 1940s, biggest oil find in Illinois history, but none of us there owned any of the royalty, so the oil never accumulated to any of the local folks at all.

Is this the first time you’ve talked publicly about the depression and the electroshock therapy you went through? Thomas Eagleton had to drop out as a vice presidential candidate in 1972 because it was revealed he went through the same thing. But just recently, we had Senator John Fetterman, who was very public about his struggles and his treatments with depression. Why did you feel like you had to keep it a secret as a politician? Do you think that it would be different today?

It probably would be somewhat different today. But this is a rural area with a lot of traditional attitudes toward those things. Poor farmers and their kids don’t seek psychological help in the midst of mental health issues. First of all, it’s not available. It certainly wasn’t available when I was growing up. But it was a combination of a lot of personal tragedies that had occurred in my life that I had never dealt with.

My sister and four of my best friends were all tragically killed in an automobile accident when I was just two years younger than her. And later on my best friend, my first cousin, who I’d grown up with hunting and fishing and so on, was the first young man killed in Vietnam from our county. After my sister’s death, my parents’ marriage kind of broke down because of the mores around the evangelical church in which I grew up. They blamed themselves for my sister’s death, because there was alcohol in the scene of the accident, and our church and our community were teetotallers. That wasn’t allowed, wasn’t even thought of. So all of that together, sort of built up from the time I was teaching school, and trying to deal with it internally, I had the breakdown.

You talk in the book about abortion being the issue that cost you the 1998 campaign. I know there progressive lakefront wards in Chicago who voted for your opponent, George Ryan. Do you think you could win a Democratic nomination today?

No, I don’t think I could win the Democratic nomination today. I won for different reasons back then, but I don’t think I could today. That issue has exploded on the political scene just because of the Supreme Court decision. And it’s even more exacerbated today than it was back then.

Why do you think that’s become the single biggest issue dividing the two parties?

I guess that’s true in the minds of a lot of people, but you know, there are millions of pro-life Democrats in this country. Most of the people with whom I grew up, who were in the Catholic Church, and the Baptist Church, we’re all good Democrats, and we’re all pro life. They believe in the principles of the Democrat Party — balancing a budget, equal justice under the law, equal educational opportunities for all of our children, protecting the vulnerable — but they’re not going to desert a basic tenet of their faith.

When you look at the breadth and depth of my commitment to those principles in the Democratic Party, I’m a good Democrat all my life. And I’ve supported people in the liberal wing of my party on almost every race that they’ve run. That issue reaches into a lot of areas, particularly in Downstate Illinois, where you had a lot of union people voting for Donald Trump and will again, a lot of those people grew up in these churches and have those beliefs. It’s one of those issues, along with guns, that have taken strong union members who would traditionally vote Democrat on the basis of their economic values, vote Republican on the basis of those issues. They’re so affiliated with the culture of their community and their faith.

Southern Illinois has become more Republican over the abortion issue. But we’re in a one-party Democratic state. How has that reduced its influence compared to years past? Because we used to have a lot of political powerhouses from Southern Illinois.

I think a lot of it relates to the motivation and the intent of the national parties themselves. The Republican Party has found out that through their concentration on the rural areas of this country, especially with the Senate appropriation of two senators to each state, that they can be very competitive in the Senate. If they win enough states, they’re not worrying about the popular vote anymore.

Donald Trump, in the last election, if I remember this correctly, he came to Evansville, Indiana, came to Cape Girardeau, Missouri, he came to the airport out here by Carbondale two miles from my home. He came to Granite City. He surrounded this whole Downstate area with his visits. We can’t get a Democrat candidate for president to visit Downstate rural Illinois. That’s indicative of the way the parties view their stance across the country. The Democrat Party has become more urban-centric, and, you know, there’s reasons for that. But in the Democrat party in Illinois, where we used to have very competitive races down here for state rep and state senate, and so on, the Democrat Party took the attitude at some point that it was more efficient and effective for them to gain ground in the western suburbs of Chicago, and it was deep Downstate where there were cultural issues that they couldn’t seemingly overcome. The focus of the state party began to lean toward expanding westward out of Chicago than Deep Downstate.

;In 1992, Bill Clinton and Al Gore went on a bus tour through Southern Illinois, and stopped in Vandalia. They did very well in Southern Illinois.

Even more recently, on the State Central Committee, in the past couple of meetings, Chairman Lisa Hernandez and John Cullerton talked about how now they’re going to focus on Downstate, because they realize that everything shouldn’t be just dependent upon the city and the expanded suburbs. I think people are beginning to see that, you know, what once was a good Democrat area can become again, with the right focus.

What issues do you have to emphasize for Democrats to win in Southern Illinois?

Health care is always a big issue in rural areas of this country. Because we don’t have the health care networks that you do in the city, we don’t have the ancillary kinds of things to back up the healthcare networks, like specialties and so on.

Communication is a big thing: Internet services, which have been wholly lacking in the rural areas of this country. I think the governor has made a good attempt on that. One of the things that the governor has done down here, which has been neglected in the past, because we have the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers here in Southern Illinois, which has the potential to be a large part of our commerce, he is taking these port districts which have never been developed before and he’s putting money into those to develop a better port facilities along these rivers, which which help are agriculture industries, and so on. So there’s a lot of things that could be focused on Downstate that would help bring back things. They’ve sort of lost their footing in the past couple of decades or so.

Senator Durbin says that he wants to be succeeded by a Downstater. Is there enough of a Democratic bench to find someone Downstate?

I think so. We’re going to have to work hard at it. I don’t know who that person would be at this point in time. We don’t have anyone strong enough in this immediate area, but certainly, there’s got to be some really strong Democrat candidates in some of the larger urban areas Downstate, like Peoria or Champaign. [State treasurer] Mike Frerichs is actually a Downstater. You’ve got Nikki Budzinski, who just won that seat in Congress. Nikki would be an excellent candidate. She’s a real hard worker. Cheri Bustos had a great 10 years in Congress. People like that would make a good impression for Dick’s seat.

People in Southern Illinois are always saying Chicago wastes all their money. And people in Chicago are always saying Southern Illinois gets more than twice as much back from the state as it puts in. What can we do to make Illinois feel like one state with common goals and a common culture rather than divided between the interests of Chicago and Downstate?

There are a lot of commonalities between inner-city Chicago and Downstate in terms of need, and those need to be emphasized as a form of unity. But here’s the thing that is so disturbing. And for me, as a Democrat, it goes to the larger issue in the country of all this misinformation that’s being put out. The Paul Simon Institute [at Southern Illinois University] conducted this very important piece of research three or four years ago in terms of who gets what with the division of tax money in the state of Illinois. Downstate Illinois gets way more than their fair share of what they send to Springfield in the form of taxes. We get back like $1.80 or something for every dollar we send. The city of Chicago gets less than $1. This idea that these separatists are putting out, which is a total lie, that somehow Southern Illinois supports Chicago, and our money is flowing to Chicago, has to be tackled if we’re going to be unified as a state: the truth has to be revealed on things like that. Because these people that are talking about dividing the rest of the state from Chicago, are getting away with just plain lies.

We would be more than a food desert in Downstate Illinois if it weren’t for the city of Chicago and their tax base. Thank God for the city of Chicago and the suburban communities that provide a great tax base for this state. We benefit from that. We have programs that require those funds to help our people. And we need to realize that and be honest about that, because the divisions are being caused in large part by people trying to misinform the public. And that’s just wrong.