When she offered a toast at April’s Time 100 Gala in New York City, Tracie D. Hall, selected for Time magazine’s list of influential people, drew attention to librarians who have faced bomb threats, firings, and even jail time for resisting a growing effort to ban books. Hall, the first Black woman to head the Chicago-based American Library Association, received a standing ovation for her passionate declaration: “Free people read freely.”

Hall, 55, recently stepped down after nearly four years at the ALA. The timing was right, she says: She had helped close the organization’s budget gap, led it through a pandemic that temporarily closed libraries’ doors, and taken stands in support of librarians thrust into the middle of the culture wars. Still, the Pullman resident, who previously worked as director of the Joyce Foundation’s culture program and operated a Pilsen art gallery, says she will continue the fight to ensure that everyone has access to books.

You took the helm at the ALA in early 2020, when the movement to ban books was growing. How do things stand now?

We are in the eye of the storm. We are seeing legislation that is punishing libraries for having books that speak to lived experiences: the memoirs and critical histories of people who have been marginalized. We also are at a moment where we are seeing parents and residents being radicalized, being coerced, being persuaded into attempting to challenge books they haven’t read. We are seeing groups that are still in the shadows but are very powerful that are really interested in circumscribing the right to read. Book censorship is really a Trojan horse for other activities that seek to limit socioeconomic and political access. U.S. representative John Lewis warned us before his death that access to the internet, and to information more broadly, would be the civil rights issue of the 21st century. But I think we will prevail, because every day I’m seeing more people wake up to how serious this crisis is.

“We have to refrain from thinking that book banning can’t happen here. We’ve seen efforts to challenge LGBTQ- and BIPOC-authored books in Naperville.”

Librarians and libraries used to be so beloved. What changed?

It is precisely because libraries have enjoyed such an important space in our public imagination that there is an effort to destabilize that. We are in a precarious place where we have gone from this rarefied position that few institutions enjoyed — especially institutions that opened their doors to everyone. We have gone from being celebrated to being contested, and that is why we really must speak out. If we see libraries as institutions erode, we will begin to see the foundation of our democracy erode as well.

How did you motivate librarians and others to stand up to book bans, even as some states ended their library system’s affiliation with the ALA?

I took inspiration from librarians. So many of them refused to walk away. They formed organizations, grassroots efforts, and mutual aid efforts to support librarians that might be cast as having ulterior motives. Dozens have been removed from their jobs because they championed intellectual freedom. At the ALA, we created the first national campaign to counter censorship: Unite Against Book Bans. We created a legal defense fund for people facing litigation or who need support because they were unjustly fired. We have a program called I Love My Librarian that awards small grants and brings recognition to librarians and library workers who are doing the work to support their communities.

In Chicago, we celebrate intellectual freedom and diversity of thought. Why should we be concerned about bans in Florida, Texas, or Montana?

What is exciting is that Illinois, under the leadership of Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias, is the first state to really push back against book banning with sanctions that penalize it. We created a template. There are at least four states attempting to replicate that legislation. And Chicago is a land of firsts. The Chicago Public Library was the first to become a book sanctuary, meaning a book on banned lists can not only be found here but is available electronically to those elsewhere who may have a hard time finding it. But we have to refrain from thinking that book banning can’t happen here. We’ve seen efforts to censor or challenge or even confiscate LGBTQ- and BIPOC-authored books in Naperville. And on the same day in September when Giannoulias was testifying at a Senate hearing on book banning, we had six Chicago-area libraries receive verifiable bomb threats. Anything that happens when it comes to censorship and book banning is going to leak into broader society and affect all of us.

What comes next for you?

My family reminds me often that they see me as an artist first. My aunt, before her death, right when I was accepting the job as the ALA executive director, said she was happy to hear about my role but said, “You know that your true calling is art.” Many, many librarians have art backgrounds or musical backgrounds or theater backgrounds. One of the reasons I feel a conviction about intellectual freedom and the right to read and freedom of expression is because the artist in me understands that we are not our true selves unless we can express ourselves. And we will never reach the full measure of who we can be unless we are allowed to question and to seek answers. I see libraries as part of that path to transformation. I’m always seeking to transform personally. I want to ask questions that lead me to higher places, and I want that for everyone. For me, reading has allowed me to better understand myself and my situation. It has given me hope in times of despair, especially as a young child growing up in a community [Watts in Los Angeles] that was underresourced. It does that for young people and adults all over the world.

Literary Sanctuary City

The Chicago Public Library makes books that have been banned or challenged elsewhere available electronically to readers anywhere. Here are three by local authors.

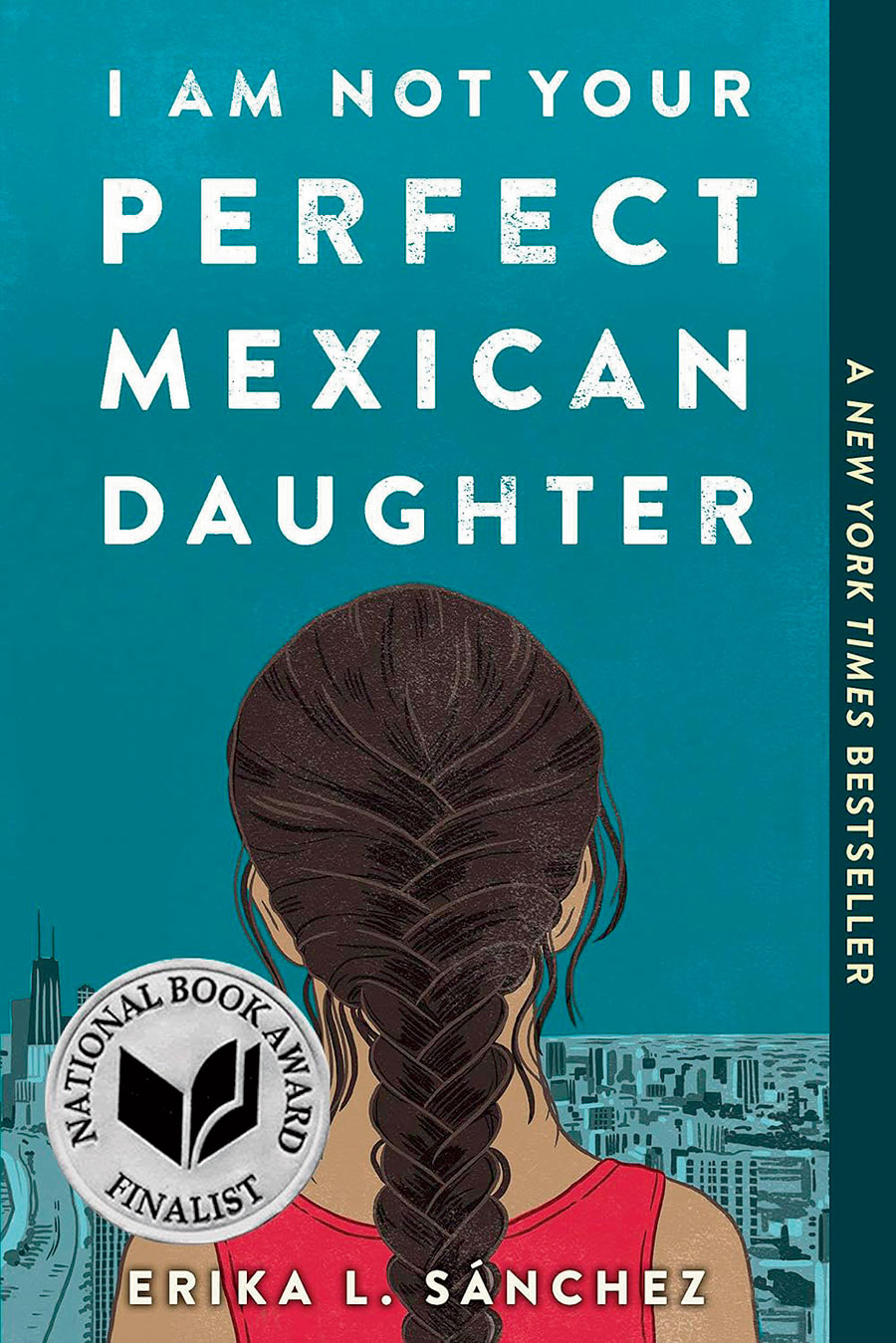

■ I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika L. Sánchez

Flagged in a Texas school district for being “anti-Christian” (the main character is critical of religion), the bestselling novel by a Chicago poet tells the story of Latina teenager coping with her sister’s death. It examines themes of sexuality, depression, and suicide.

■ Gracefully Grayson by Ami Polonsky

This middle grade novel, by an English teacher in the suburbs, is about a transgender girl coming to terms with her identity as she grapples with bullies. It was banned in Duval County, Florida.

■ Mr. Watson’s Chickens by Jarrett Dapier

This children’s book features a same-sex couple. A virtual presentation at a downstate school was canceled for fear of backlash — but rescheduled after the author, who lives in Evanston, strategized with the principal on how to manage parents who might oppose it.