There’s an unexpectedly personal aspect to Court Theatre’s staging of a new play about civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael. “Charlie used to be babysat by Stokely when he was a kid,” playwright Nambi E. Kelley says, raising an eyebrow to punctuate the statement of unlikely fact. “Charlie” is Charles Newell, the longtime artistic director of the University of Chicago–affiliated theater in Hyde Park, who’s retiring this summer after three decades at Court’s helm.

Newell and the late Stephen Albert, who was Court’s executive director until his death in 2017, approached Kelley with the project years ago. She had just penned an impressive stage adaptation of Richard Wright’s Native Son for Court in 2014. “They came to me,” Kelley recalls, “and said, ‘We would love you to write this.’ ”

If Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution, which runs May 24 to June 16, had a long gestation, that’s partially because the playwright wanted to get the story right: “My dad was a historian. He’s passed away now, too. But he gave me everyone. He gave me Malcolm X when Malcolm was being demonized in the press. And he gave me Stokely Carmichael. My dad was a revolutionary, and he used to march, protest, organize, all that stuff back in the day. It was a nice way to be able to honor my father, to be able to continue the legacy of what he was doing as a historian and a documentarian and a teacher.”

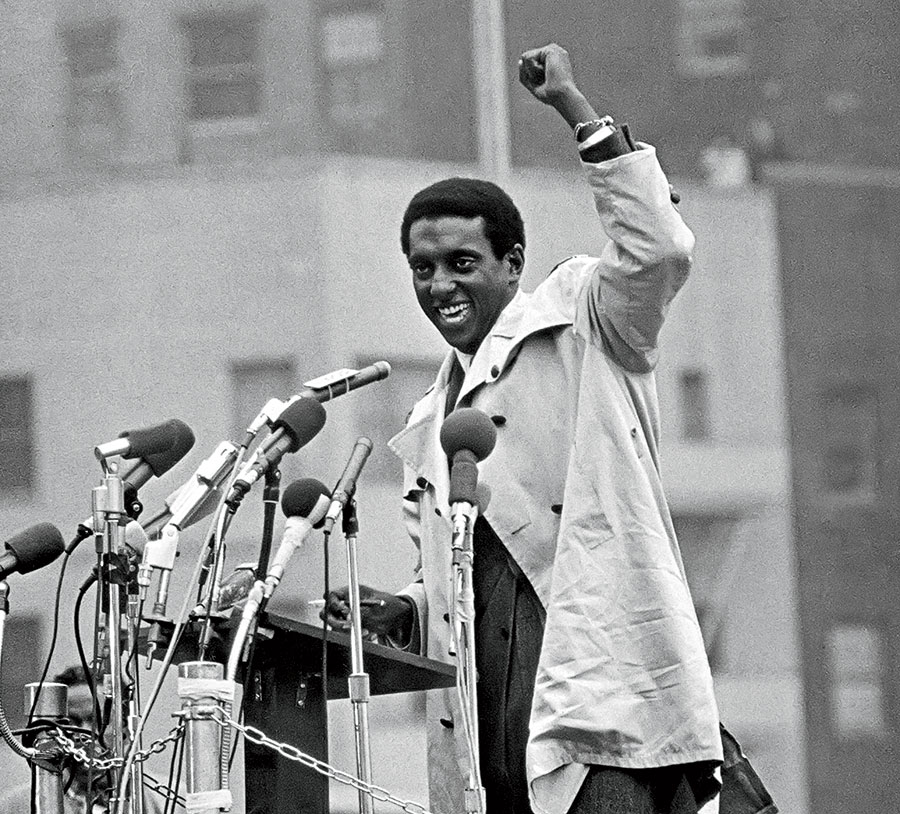

Carmichael, perhaps best known for popularizing the term “Black Power,” later adopted the name Kwame Ture. He left the United States in 1969 and spent most of the next three decades living in Guinea before his death from prostate cancer in 1998 at age 57.

Kelley wanted to bring “a female perspective” to bear on Carmichael’s life, but her initial approach gave the title character short shrift. “The concept was that it was going to be Stokely through the eyes of the women who knew him, right?” she says. “So the setup was his funeral. Miriam Makeba [the South African singer who married and divorced him] was there, and May Charles, his mother, and [activists] Gloria Richardson and Diane Nash. But it kind of muted him in a way I didn’t find interesting theatrically. You know, if you kill a character at the top of the show, he doesn’t really get a lot of agency.”

Kelley refocused on a new conceit: Carmichael and his mother negotiating the end of his life. “It’s the perspective of a mother who deeply loves her son and deeply does not want him to accept the fact that he’s dying,” Kelley says. “There’s a video where he actually interviews his mother, which I think is probably where I was like, Oh, what if this was the premise of the play?”

A speech at Howard University during the last year of Carmichael’s life was another touchstone. “I think he has six months left to live. He’s got a head full of gray hair. And he’s very clearly ill. But he’s so on fire for what he’s doing that that almost takes over,” Kelley says. “He’s sweating, right? I mean, he was doing chemo, so it was wearing him out. So that became sort of the crux of what my play is: ‘I gotta get this out. It’s more important for me to do this than what’s happening to me physically.’ ”

Though she’s now primarily based on the East Coast, Kelley, who grew up in Bronzeville and graduated from DePaul University’s theater school, has a packed Chicago itinerary this spring. Concurrent with Stokely (which is directed by Tasia A. Jones and stars Anthony Irons in the title role), Lifeline Theatre in Rogers Park is mounting a new production of Kelley’s Native Son, May 10 to June 30. Around that time, Kelley, who started her career as an actor, will be wrapping up her first stage appearance in five years, performing in the August Wilson play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone at the Goodman Theatre April 13 to May 12. “A production of Joe Turner that the Goodman did when I was in high school was the reason I became an artist,” Kelley says. “So it’s a wonderful homecoming.”