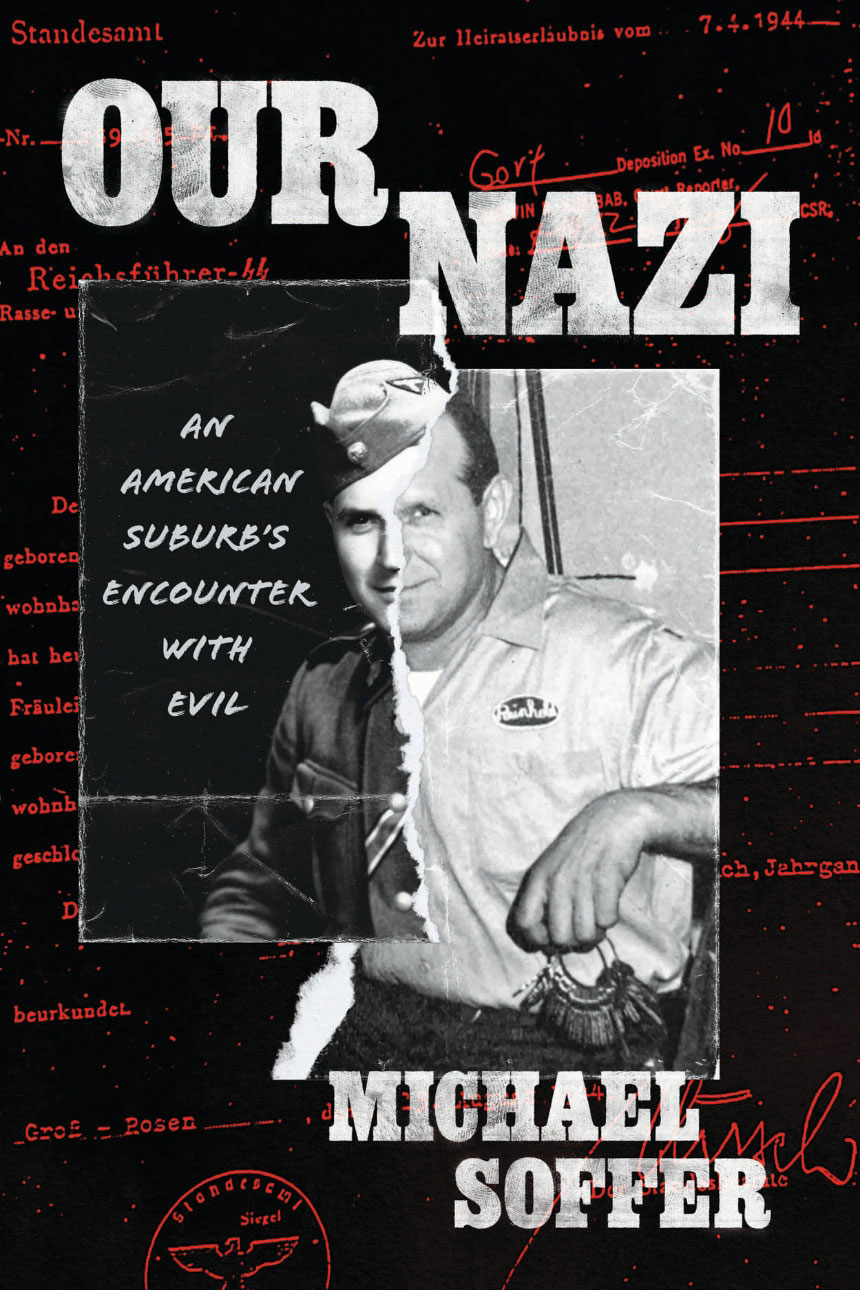

As a student at Oak Park and River Forest High School in the early 2000s, Michael Soffer would hear chatter about the discovery in the early 1980s of a Nazi — an actual Nazi, as in SS member and concentration camp guard — working as head custodian at the school.

Later, after Soffer became an OPRF history teacher, he and his students researched the incident. One revelation: In Oak Park, a town that has long prided itself on its progressivism, there was a groundswell of support for retaining the custodian, Reinhold Kulle. Out of that came Soffer’s new book, Our Nazi, out October 2 by University of Chicago Press and excerpted by Chicago.

It’s easy to dismiss that reaction as a relic of the past. But note that this summer Soffer left the school to take a job with Lake Forest High School. In his resignation letter, he cited “the continued toll of antisemitism” at OPRF.

Though Soffer declined to elaborate on the reasons for his departure, he talked with Chicago about his deep dive into the discovery of Kulle’s secret and the surprisingly divided response in the community at the time.

What did you think when you first heard talk of a custodian with a Nazi past working at the school?

It was something that was always kind of talked about, sort of referenced in passing, and, I always thought, oddly described as a quirk in Oak Park’s history, which made me uneasy. I started attending the high school only 15 years after this had happened, and so all the players from the school side were still employed there. It was very much in the living memory at the time.

Given that Oak Park is a town that wears its liberalism on its sleeve, were you surprised to learn about the community’s reaction, that there was this strong resistance to removing Reinhold Kulle from the school?

On some level, it’s very surprising, because it’s so antithetical to how the community perceives itself, and yet as I was researching more and more and thinking about my experiences as a teacher, there are things about it that made it make sense. It’s easy to say that Oak Park is this progressive community, but there’s a lot of complications, especially in a community that so values its own traditions and its history. There’s a loyalty part of that.

I should add that Oak Park’s history, with regard to the Jewish community, is not one of progressivism. Recently a friend found in the Chicago Jewish archives an oral history with an Oak Park Jewish woman who talked about not being allowed to join clubs when she was at the high school. This would have been in the ’50s. And both of the local synagogues had a lot of trouble getting their land purchased. The two private clubs in town, the River Forest Tennis Club and the Oak Park Country Club, weren’t open to Jews, as well as plenty of other groups. So there was this strand.

What prompted you to explore the Kulle situation as a book?

I had no intention of writing a book. I was looking for guest speakers. In 2018 the high school had experienced a slew of antisemitic hate crimes, and in the absence of a larger district response, I created a Holocaust studies course. As a teacher, you always think, Well, the only way I can respond is pedagogically and with good curriculum. That’s how we solve problems. I wanted to present to my students ways of making this history relevant and personal.

If you find out that you are friends with a monster, that reflects on you. And a lot of the defense of Kulle and other Nazis from neighbors and colleagues and friends was really an act of self-justification.

That was easy to do in terms of survivors, but I also wanted to give them a nuanced portrayal of perpetrators, and we had this local case. I did some research on Kulle’s background, and presented it to my students, and they could not have cared less about his Nazi years. They kept saying, “Well, what happened when he was caught?” This was their community. Many of the kids are generationally linked to Oak Park: Their parents had gone to the high school.

So we started it as a research project in class. We had digitized editions of the local newspapers: the Wednesday Journal and the Oak Leaves. We started going through them. We made a list of names that kept coming up in stories. Then I’d try to contact those people: “Could you come in to talk about it?” Once I started calling people, they were unloading 40 years of pent-up emotions, on both sides. And I thought, Okay, this is maybe a little more than just finding a guest speaker. I was explaining this to my wife, and she said, “So you’re gonna write a book?” And I said, “No, I’m a high school teacher in the middle of the country. I’m not gonna write a book. How would I?” But over the next few months, I came around to the idea that there was a larger story to be told about how Americans responded to the efforts to bring Nazis to justice, that this case was a microcosm.

It’s an interesting phenomenon. You’d think you’d be horrified to learn a person you knew well had been revealed as a Nazi. But when you have already forged a relationship with this person, as a friend or co-worker, I’m guessing it gets more complicated?

Yeah, absolutely. What I argue in the book, through the characters going through this, is that I don’t think that Kulle himself was at issue. In other words, if you find out that you are friends with a monster, that reflects on you. And a lot of the defense of Kulle and other Nazis from neighbors and colleagues and friends was really an act of self-justification.

How receptive were people to speak to you?

The folks who pushed to have Kulle removed were beyond receptive. They had been vilified in the local press at the time, so having their story told fairly for the first time was vindicating. There are two heroines of the book: Rima Lunin Schultz and RaeLynne Toperoff, who really pushed and pushed and pushed the school to have him removed. I knew of Rima Lunin Schultz as a historian, because she’s the preeminent scholar of Jane Addams, but I didn’t know about this other part of her. And so it was really fascinating to see that they had faced a lot of vitriol in the community. They had lost friends over this and were perceived as the bad guys — the vengeful Jews, that kind of thing. And people never apologized to them.

What about Kulle’s supporters?

I reached out to pretty much everyone who had written a letter to either local paper — several hundred people. The vast majority of those who supported Kulle didn’t respond. Granted, this was 40 years ago, and you wrote one letter to the newspaper when you were 32 and now you’re in your 70s and some random person is calling you up. I get it. So supporters were cautious with me. His friends who did not work at the high school were not willing to talk at all.

Those who had worked at the school were more open to conversations, especially when I said that I was trying to get a good understanding of what the discourse was in the community. I started teaching at the school in 2007, and some of the folks at the school who were in this scenario retired between 2005 and 2010, so that was easier because we were colleagues. Some of them, though, I had to really lobby hard.

When you sat down with Kulle’s supporters, were they open and honest about their thinking at the time? Or did they try to sugarcoat it?

Some of both. There were a few people who were even somewhat threatening. One of the first people I talked to said, “I’d hate to have you portray him in a negative light,” which I thought was an odd thing to say about an admitted Nazi camp guard. Somebody else said, “I wish people would leave this poor man alone.” One woman who I didn’t end up using in the book said, “The real problem in this situation was you Jews and your self-righteousness.” That’s a really bold way to defend a Nazi, right? By attacking Jews.

His friends were not what I expected. A lot of them were talking about issues like workers’ rights, and what does it mean if we remove somebody while there’s still a trial going on? And what does that mean for other accusations? I hadn’t thought about that before.

Another thing that’s interesting: The Holocaust became this thing in the late ’70s, right? Between the Skokie case [in which neo-Nazis sued to march there] and the Holocaust miniseries with Meryl Streep, it experienced this kind of historical phenomenon, and then it really gets into educational curricula in the 1980s. So the teachers who were navigating this at the high school in 1983 weren’t particularly knowledgeable. People didn’t really understand what it meant that he was a camp guard and what it meant that he was in the SS. And a lot of people didn’t understand that the deportation trial was not to determine whether he was a Nazi. It was whether he had lied on his visa.

Also, the two local papers were very much misreporting what was happening, and one of them in particular, the Wednesday Journal, was decidedly in Kulle’s favor in articles. They would interview the defense attorney and take his word as fact, and that really shaped the way people in the community perceived the case.

Early on, the OPRF superintendent at the time, Jack Swanson, backed Kulle. Your book really gets inside his thought process. Did he see talking to you as an opportunity to come clean, like he had a debt to pay?

No, I don’t think I would say that. He’s a nice, thoughtful man who was asked questions and answered them openly and honestly. And that was really helpful. He was an absolutely beloved figure in Oak Park, and I think he cares deeply about the school. But no one I interviewed, looking back, thinks they were on the wrong side.

Related Content