Indiana has an inferiority complex. And for good reason. Fitting for a state known for doing things second best, its main claim to fame is that it’s been home to the second-most vice presidents (six, behind New York’s 11). It has a sort of big city, whose nickname is India-no-place, but the rest of the state is composed of small towns with little opportunity. “Hoosiers struggle desperately to prove to themselves and the world that they have a higher function than simply filling up the space between Chicago and Cincinnati,” wrote Andrew Ferguson in his book Land of Lincoln.

In this attempt to stay relevant, Indiana has a long history of trying to poach businesses from Illinois. In the early 2010s, when Mike Pence was governor, the state placed a series of “Illinoyed?” billboards along Interstate 90, promoting what it claimed was Indiana’s superior business and regulatory environment. Among its prize recruits: manufacturer of plastic parts for fans and blowers and a packaged meat company.

The billboards are gone, but Indiana, which isn’t satisfied with just being Indiana, is still after whatever it can take from Illinois. Lately, the state has been trying to steal land, residents, and even a beloved sports team from its more relevant neighbor to the west.

In February, the Indiana House of Representatives passed a bill to form the Indiana-Illinois Boundary Adjustment Commission, whose goal is to capitalize on downstate Illinois’s disaffection by seizing some of that region. The sponsor, House Speaker Todd Huston, was moved to act when seven Illinois counties passed referendums in November to explore forming a state separate from Chicago. “We dug a little deeper and figured out that 33 counties have taken a similar vote,” Huston said during a hearing. “If those 33 counties want to join our state, we welcome that.” Why would they? Illinois’s income tax is half again as high as Indiana’s, and its property taxes are about triple, Huston pointed out. “To Illinois counties feeling unheard or unrepresented, we hear you, and we would like to welcome you to come back home again to Indiana.”

His message resonated with at least one target resident. G.H. Merritt, founder of New Illinois, a group agitating for secession from Chicago, traveled from her home in Lake County to Indianapolis to testify in favor of the bill. “Illinois outside of Cook County has much more in common with Indiana,” she told a legislative committee, admiring that Indiana has a budget surplus, while Illinois continues to “drown” in billions of dollars of pension debt.

Here in Illinois, state Representative Brad Halbrook, a Republican from Shelbyville, introduced his own bill to create an Illinois delegation to Indiana’s boundary commission. Halbrook’s home county, Shelby, overwhelmingly passed a referendum to look into seceding. He sees a more congenial political environment in Indiana, which has Republican supermajorities in both houses of its legislature. In Illinois, of course, the Chicago area dominates the rural hinterlands, while in Indiana small-town voters are in charge. “Most of Illinois is an agricultural state,” Halbrook tells Chicago. “There’s just a different lifestyle. Iowa, Illinois, Indiana — that’s the Corn Belt. We have to have conversations to talk about these rural concerns.”

Those include hot-button social and political issues. Scott Carpenter, a Hoosier who is a member of the group Downstate Illinois Secession, testified at the Indiana hearing about the need to free Illinoisans who don’t live in the Chicago area from the state’s “abortion centers, legal marijuana, and immigration sanctuary laws.” He even suggested the states swap Lake County, Indiana, which already functions as a suburb of Chicago, for southern Illinois.

“We are in the Chicago media market. Not all teams play where they’re named: The New York Jets and Giants play in New Jersey.”

— Indiana state Representative Earl Harris, who wants to bring the Bears to northwest Indiana

Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul is looking to put an end to all this talk. In response to news about Indiana, as well as Missouri, sniffing around our borders, his office felt compelled to issue a legal opinion stating that the downstate counties “do not have the authority to secede from the state of Illinois and join another state.” Under the U.S. Constitution, a change in borders must be approved by both states and by Congress. Illinois Governor JB Pritzker has already called Indiana’s annexation proposal “a stunt” carried out by “a low-wage state that doesn’t protect workers, a state that does not provide health care for people when they’re in need.” Nice burn, JB.

But would Pritzker’s hometown of Chicago really miss southern Illinois? Probably not. Let’s face it, the big city regards the rest of the state as an irrelevant agricultural appendage.

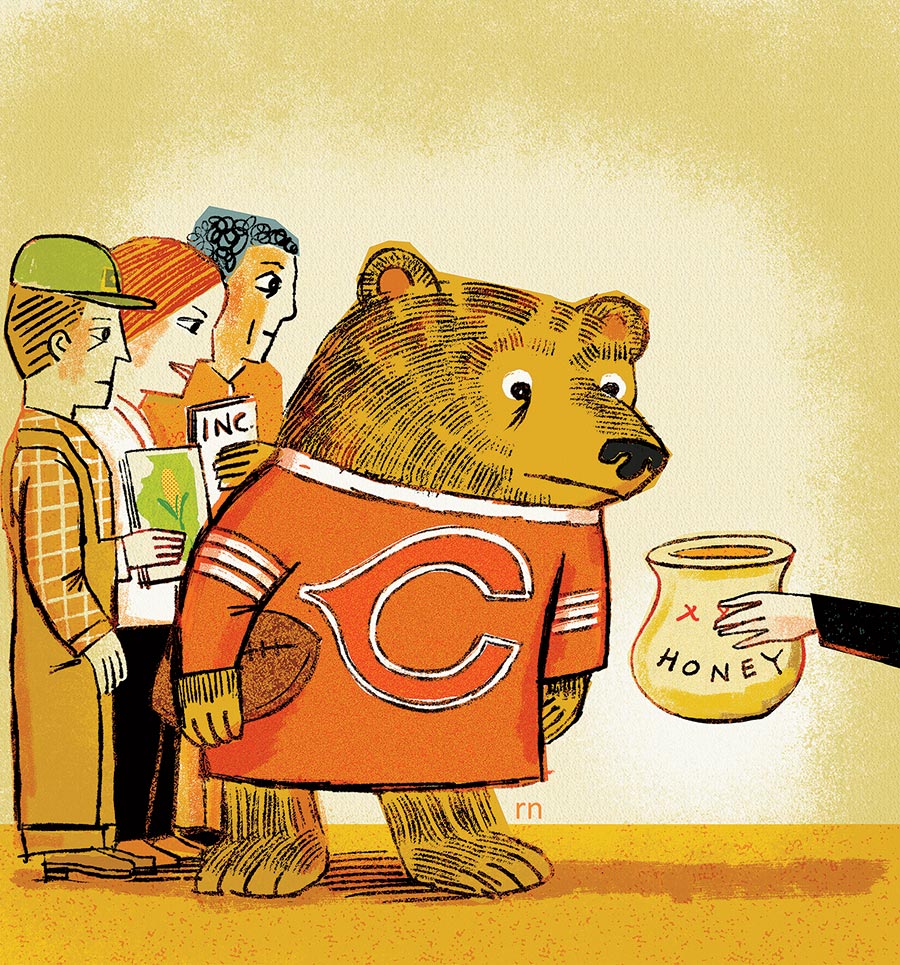

But here’s what we do care about: The Hoosiers are also going after an institution central to our civic identity, the Bears. Another bill making its way through Indianapolis would create a professional sports development commission to lure a franchise to northwest Indiana. The sponsor, Representative Earl Harris of East Chicago, told Chicago that the region would take any pro team, but that the bill was drafted with the Bears’ search for a new home in mind. Northwest Indiana, after all, is already Bears country. “We are in the Chicago media market,” Harris says. “When you look at it on the national side, not all teams play where they’re named: The New York Jets and Giants play in New Jersey.”

This is not the first attempt that the region has made to swipe our NFL team. In 1995, a business group there proposed a $482 million stadium and entertainment complex to entice the Bears at a time when the team was demanding Chicago make upgrades to Soldier Field. For a short period, there was serious talk of a Gary Bears, but the plan fell apart when Lake County, Indiana, refused to levy a 0.5 percent income tax to fund a stadium. Back then, Bears fans rejected the idea of crossing state lines to watch their team, but Harris believes that improved South Shore Line service would draw them now. “People could take the train and watch professional sports and do their thing,” he says.

While Huston and Harris see their efforts as merely Hoosier hospitality, this feels a lot more like Hoosier hijacking. If they want to build a bigger and better Indiana, one that’s a destination and not just a drive-through, let them build it from inside the borders they were given.