This month having brought us the Chicago beer issue, I was looking for information about the Second International Brewer’s Congress, held in Chicago in 1911, and stumbled across something completely unrelated: the first movie theater, insofar as it was the first place for which tickets were sold to see projected, moving photographs, was the Zoopraxographical Hall at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Hyde Park.

Its builder was the pioneering photographer Eadweard Muybridge, born Edward Muggeridge. He had been in Chicago before, lecturing before the Art Institute on his then and now legendary photographs of men and animals in motion, demonstrating the wisdom of the ancients:

An interesting illustration represented a buffalo robe taken to Paris by La Fayette. Mr. Muybridge used it in support of his argument that the aboriginal artists of any country, while, of course, lacking in power to execute, were superior to their followers in observation. The robe bore on its flesh side specimens of animal painting by North American Indians of the revolutionary periods. A number of the animals represented were horses, and a comparison between them and some of the instantaneous photographs showed that the aboriginal artists knew much better how a fox walked and [illegible] than many of the animal painters of today.

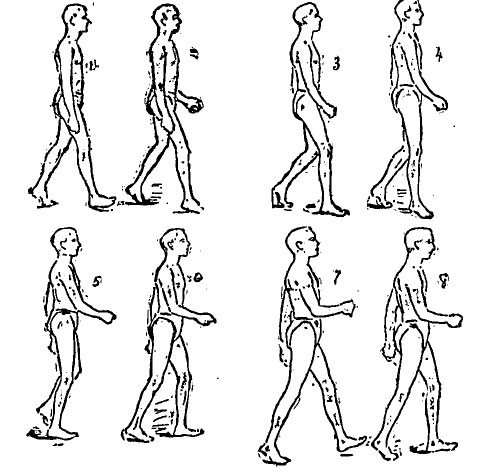

The Tribune attempted to do the same by reproducing Muybridge’s instantaneous photographs in sketch form:

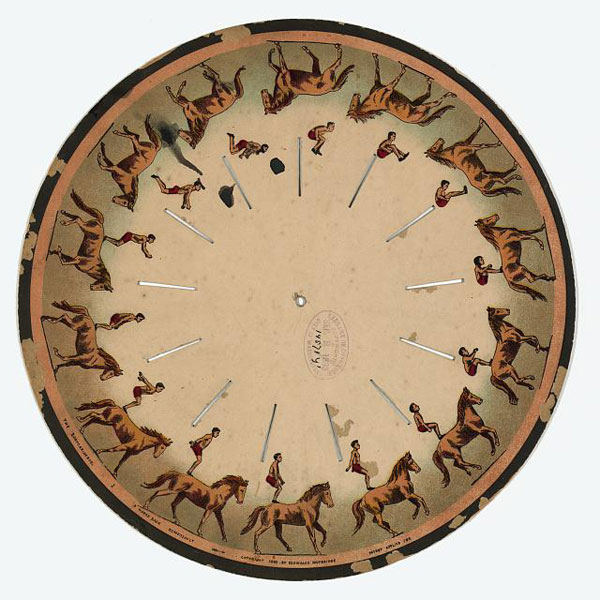

But Muybridge’s exhibit at the Columbian Exposition was of a much grander, and riskier scale. According to biographer Brian Clegg, Muybridge plunked down $6,000—over $140,000 in 2010 dollars—with the hopes that he’d make the money back on tickets and beautifully illustrated zoopraxiscope fans, some of which were painted by Thomas Eakins, and which probably also qualify as the first swag in the history of motion pictures:

Muybridge also sold his book Descriptive Zoopraxography: Or the Science of Animal Locomotion, which featured not just elephants and baboons, but "Grecian dancing girls" and a man hitting a baseball, with instructions for how to turn the picture into your own zoopraxiscope:

He didn’t stop selling there; the book came with entreaties to buy even bigger zoopraxiscopes (nine inches in diameter, fifty for $5, or $120 today), or a subscription to all 781 of his plates, for the substantial price of $500.

But Muybridge’s neighbors in the White City were not only the dancing girls of the "Streets of Cairo," but an exhibit of $1,000,000 in gold coins, a model of the Eiffel Tower, and the Temple of Luxor. For all its technological miracles, the Columbian Exposition foresaw the Vegas Strip as much as anything else.

The experience put the aging Muybridge off the zoopraxiscope. After spending much of his life setting the world to film, he eventually returned to his native England, though his obsession with simulacra were not necessarily over. A popular story about Muybridge is that his final goal was to build a scale model of the Great Lakes in his garden, capturing again the world in miniature and reflecting his view from the White City in a way his cameras couldn’t capture. But whether he actually intended to or not is still unknown. If he did, he did not complete enough of it for anyone to see, leaving his final framing of the world without so much as a shadow.

Photographs: Chicago Tribune, Library of Congress, Descriptive Zoopraxography, The World Columbian Exposition