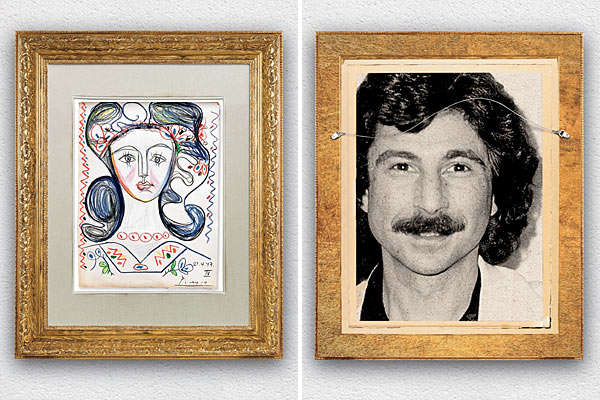

A counterfeit Picasso, just one of the high-quality fakes in Michael Zabrin's global scam that made millions of dollars and spanned decades

When Ricki Zabrin looks back on her life in the eighties, she remembers how her Northbrook neighbors used to wonder about her husband. Unlike the button-down breadwinners on the block who set off for the office each day in pinstriped suits with attaché cases in hand, Michael worked from home. He was a birdlike little man with a carefully trimmed mustache and styled curlicues of black hair that cascaded to his shoulders. When he did dart out of the house, he was in full plumage, which could mean a fire-engine-red suit and a purple tie with a belt and boots made of matching alligator skin. His wheels were equally flashy: a sleek Porsche Carrera. “Of course,” Ricki laughs, “everyone thought he was a drug dealer.”

Her husband was indeed a dealer, but what he dealt could not have been more different from dope, and that’s what she found so funny. Zabrin sold art, and not just any art—primarily limited edition prints from the 20th-century masters Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dali. A consummate salesman with a whimsical sense of humor, he plied the best-known gallery owners in Chicago and across the country, wielding a portfolio case as big as he was. According to Ricki, his clients were always eager to meet with him—“sometimes,” she says, “just to see what he was wearing.”

More recently, Zabrin’s outfit would have been easier to predict. For almost three years, he has worn a pumpkin-colored canvas jumpsuit issued by the Kankakee County jail. When the 59-year-old Zabrin sat for an interview this past July, few traces of the natty, mirthful hipster remained. A grease-pencil number was scrawled over his breast pocket, and a yellowed, tattered undershirt showed above his top button. His clean-shaven face was drawn and pale; the curly hair closely shorn. His figure, once so slight, had puffed out like a penguin’s as he sat cooped up in the crowded jail, waiting for transfer to a federal prison. In all the time he’d been there, he said, “I haven’t seen the light of day.” He grew more ashen as he contemplated the confinement to come. Even with time served, he faced at least another four years for mail fraud—all totaled, a relatively heavy sentence for a nonviolent offender; more fitting for a drug dealer than an art dealer.

But like the artwork he sold, there are few straight lines or sharp corners to Michael Zabrin’s story—starting with the fact that this was not his first sentence for fraud. A decade before, he took a plea for the same offense: selling prints that were not limited editions, as he claimed, but unauthorized, unlimited reproductions with forged signatures.

Sales of such fraudulent art in the United States are in the “many millions of dollars” each year, according to Sharon Flescher, the executive director of the International Foundation for Art Research. Much like the drug trade, those who produce the goods are insulated from the ultimate consumers through elaborate international distribution syndicates that use layers of dealers and retailers.

However, the same government investigators who have tried to stop this fraud freely admit that no civilian has done more to expose the counterfeit art syndicates than Michael Zabrin—both during the nineties and in the new millennium. He not only identified key players in the trade but also engaged in taped conversations to incriminate them. His efforts helped shut down the largest known source of fake prints and some of the prestigious galleries and dealers selling those prints. But while his stellar cooperation brought Zabrin a reduced sentence the first time around, his lawyer argues that it only got him into more trouble the second time, leading to behavior that proved more detrimental than his initial charges.

Zabrin’s personal troubles aside, how did a self-made hustler from the streets of Chicago’s North Side, who could count his overseas trips on one hand, come to be at the center of an international fraud ring with tentacles that stretched from the world’s toniest art galleries to clandestine printing plants in New Jersey, Italy, and Spain? An even bigger question: Why, after wrecking so much of the illegal trade the first time, did he return to it again? The answer is as uncomfortable for Zabrin as for the gallery owners who continued to clamor for his tainted goods.

Like most of the people he worked with in the art world, Michael Zabrin did not have a background in art. Growing up in the striving middle-class neighborhood of Rogers Park, he set his sights on commerce instead. As a teenager, he started his own business, cleaning boats in Burnham Harbor. After graduating college, he worked at the Chicago Board Options Exchange and then, in 1976, moved to San Francisco, where he bought a seat to sell options on that city’s new exchange. Within a year, he says, “I bombed out.”

Zabrin returned to Chicago with his savings gone. But his desire to wheel and deal persisted. Back in his teens, on the advice of a friend’s mother, he had started buying collectibles. “She collected Boehm porcelain animal figurines and would tell me how the value kept going up,” he recalls. At first, Zabrin bought Boehm pieces. Later he began collecting prints as well: a Dali here, a Norman Rockwell there, or a Victor Vasarely, the op art pioneer who drew large 3-D geometric shapes in bright colors. He acquired each piece like a find in a flea market, hoping that one day it would go up in price. Although collecting art had been no more than a hobby, he began to wonder if it could be a career.

In 1977, a friend encouraged Zabrin to ask an enterprising art dealer for a job. With his black goatee and accent, Jean-Paul Loup was the epitome of the French art aficionado, but he quickly put Zabrin at ease. As luck would have it, he had a large number of Dali prints he had picked up in France, and he needed someone to travel around the States to show the works to gallery owners.

Although Loup did not have his own gallery, he sold directly to the public through the mail, describing himself as “probably the largest retailer of graphics by Salvador Dali.” One of his packets contained a glossy photograph of Dali’s Venice. Offering a price of $375 for the lithograph, Loup claimed that the same piece might cost $600 to $850 in “an average American gallery.” He added (in all capital letters): “I think that this will be the last opportunity you will ever have to acquire such a large and superb lithograph hand-signed by Salvador Dali at such a low price.”

He also promised to include with each purchase a certificate of authenticity, which would vouch that the print was issued in an edition limited to 450. He vowed that each piece was marked with a unique number and that the “lithographic plates were destroyed upon completion. Therefore, no further edition will ever be pulled.” Loup’s assurance that there would be no more prints left the impression that the limited edition could only go up in value.

According to Zabrin, the gallery owners rarely looked for such assurances of authenticity. In fact, as he soon discovered, selling art to galleries was not much different from selling anything else. All he had to do was call for appointments, show up on time with the case of prints, and listen to the client. He found most gallery owners to be a fun-loving bunch, so he could wine and dine them at lunch or dinner. When he returned for another visit, he would bring a little gift and the master prints that they were most likely to sell.

Before long, he learned about prints that some gallery owners were unable to sell. On consignment, he would shop those pieces to other clients who might find them more suitable. Soon he was making more from these consignments than he was from Loup, so he set off on his own to become an independent dealer. He quickly settled on the quartet of masters that would be his stock-in-trade: Miró, Chagall, Picasso, Dali.

In 1979, during one of her regular visits to marshall Field’s, Zabrin’s mother sized up a button-cute brunette behind the makeup counter and decided the young lady would be a perfect match for her son—she had even majored in art. But, says Ricki, “by the time I met him, he knew more about art than I ever learned in school.” So of course she loved his job. “He just seemed to meet the coolest people, and they got him into the coolest places,” Ricki remembers. “They all really liked Michael and how nutty he could be. It would bring out their crazy side too. Even the ones who were very suit-and-tie.”

When the couple married in November 1982, they had their honeymoon in Hawaii as the guests of Bill Mett, the owner of Center Art Galleries, who had quickly become one of Zabrin’s biggest customers. Originally a lawyer and a businessman, Mett had bought his first gallery with the intention of converting it into a clothing store. But once he saw the whopping profit margins in art sales, especially from prints, his plans changed. He kept the gallery but upgraded the lighting and décor to make art as alluring as the jewelry and handbags in Hawaii’s high-priced boutiques. He expanded the concept across the islands, opening locations that adjoined hotels or malls favored by tourists.

Back on the mainland, other gallery owners had also embarked on rapid upscale expansions. These art megamerchants adopted the silken pressure tactics perfected by other luxury retailers to goose sales, such as the weekend trunk show—a favorite of the fashion boutiques—or Sotheby’s-like auctions.

Zabrin became so busy lugging his oversize case to trunk shows and auctions that he got a hernia. Sales were no longer a problem. Prints from his quartet of masters had practically fueled the nationwide gallery expansion on their own. His future now depended on finding a reliable source for his merchandise.

Increasingly, Zabrin had come to rely on one man, Philip Coffaro of Mineola, Long Island. His gallery was also, unabashedly, a frame shop. With its narrow windows and barnlike façade, it could have been a video store or a pizza parlor. In person, Coffaro had a similar unprepossessing vibe. He dressed in casual clothes and kept his hair pulled back in a ponytail. But despite appearances, he was tremendously influential in New York’s art community as the founder of Artexpo, now among the biggest art shows in the world and held each year in Manhattan.

Although Coffaro had no trouble supplying his own certificates of authenticity for the prints Zabrin purchased, it became clear that “limited edition” was a fairly transparent fiction. “It couldn’t have been too limited,” Zabrin says, “if I could buy as much as I wanted of any print. I would go out to see Phil every six weeks, and he’d ask what I needed beforehand so he could have it ready. I even got a volume discount.”

It wasn’t long before Zabrin learned that Coffaro had his own major source for prints. In the world of fraudulent art, this source proved to be the equivalent of all the poppy fields of Afghanistan and all the drug lords of Mexico rolled into one. Most surprising, he was a respected New York publisher named Leon Amiel.

* * *

Photograph: (Picasso print) Candice C. Cusic/Chicago Tribune

The calm before the storm: Michael Zabrin and his wife, Ricki, at a charity ball in the early 1990s

Often those who were caught up in the shady world of limited edition art prints claimed connections to the great masters that later proved false. But in the case of Leon Amiel, there is no doubt that he had legitimate ties to legendary artists, and for a while these connections offered him protection from the authorities.

Although born in New York, he developed a love for all things French while stationed in France during World War II. He returned stateside—briefly using Léon as his first name—and operated a few French bookstores before he started Leon Amiel Publisher, listing offices in New York City and Paris. He specialized in books about 20th-century art and professed to be a trusted friend of the featured artists. He published more than a dozen volumes on Miró and was the author of one. Amiel wrote that he had inspired Chagall’s Exodus series of paintings when he commissioned him to illustrate a Hagaddah, the prayer book for the Passover service. Amiel’s wife, Hilda, claimed that they were on such intimate terms with Dali that the artist asked their 28-year-old daughter to dance for him in the nude (she refused).

Whatever the truth about Amiel’s actual relationship with the stars, investigators now believe that he used the illustration plates from his books in ways that the artists never intended or authorized—namely, to mass-produce their works and pass off the fraudulent copies as authentic limited editions. His operations geared up in 1972, when he imported several high-speed color printing presses from France.

Miró prints were more complicated to reproduce on Amiel’s presses since most had been etched by the artist on a copper plate colored with special tints. Amiel supposedly imported his phony etchings from craftsmen in France.

It is now believed that Amiel was worth as much as $40 million by the mideighties—most of it made through illicit prints. Alternately charming and crude, he had both the appearance and manner of Zero Mostel’s character in The Producers. While he kept the religiously observant Hilda and his two daughters in a mansion on Long Island, he spent most nights with his mistress in a Manhattan pied-à-terre. When he did return to the family home, investigators say, it was to play pinochle with his pals. Despite Amiel’s reputation for wealth and European refinement, a Long Island neighbor later told reporters that he would belch loudly and once showed up for lunch in his pajamas.

When, on occasion, fraudulent prints were tracked back to him, Amiel was ready with a cagey reply. He hinted at nebulous authorizations from the artist, much like the ones he often had for his books, or pretended that the print was never meant to be more than a “lithographic interpretation.” In regard to the galleries that sold his prints as authentic limited editions, he told The New York Times, “I don’t know how these people sell to the public. What they claim and how they sell it is something I don’t get involved with.”

To maintain his insulation from “these people,” Amiel depended on a tiny band of only the most trusted dealers. He rebuffed Zabrin’s advances until Zabrin discovered that one of his best friends in the art world was distantly related to Amiel. It still took months before Zabrin was granted an audience. An Amiel employee picked him up at LaGuardia Airport in the boss’s Rolls-Royce and then, to Zabrin’s surprise, instead of heading toward Manhattan, drove to an industrial park in Secaucus, New Jersey. There the company was ensconced in a sprawling one-story brick complex that appeared more suited to a grocery warehouse than a book publisher.

There was nothing impressive about the interior either. Amiel, wearing work clothes, greeted Zabrin warmly and then took him to his office to show the prints he had ready for sale. Zabrin made an initial buy of about $25,000. He would sell the lot for $50,000.

From what Zabrin could see, Leon Amiel Publisher was a family business. His meetings with Amiel were often interrupted by Amiel’s middle-aged daughter Kathryn, who was usually in a state of high anxiety, which her father would allay in a calming voice. Her son, oddly named Leon Jr., swept up in the back, and Amiel’s brother, Sam, would drive Zabrin back to the airport, sometimes with a jar of his homemade pickles as a parting gift.

Amiel made little pretext of his prints’ authenticity. Most of those that he displayed had no signature. If Zabrin chose any for purchase, he remembers, “his daughter taught me to leave the room.” When he was called back half an hour later, the masters had seemingly materialized like the tooth fairy and left behind their signatures.

With access to such a mother lode, Zabrin saw his sales shoot above $1 million a year. His profits skyrocketed too. A Miró he bought from Amiel for $1,500 could easily fetch $3,500 from a gallery—and sometimes as much as $10,000. He started placing ads for his prints in the art trade magazines, with the phone number 498-MIRO.

But Ricki kept her job behind the makeup counter. Zabrin’s success only ratcheted up his compulsive behavior, and sometimes he could spend as much as he made. Often his temptation was art. As soon as he sold one portfolio, he’d invest in another. Ricki remembers him covering the living room floor—wall to wall—with his latest set of prints, reveling in the shapes and colors. But there were other temptations too: an expensive bout with cocaine (he never drank) and multiple gambling junkets to Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe.

Driving Zabrin’s frenetic behavior were ominous clouds that started to hang over the world of fine-art prints in the late eighties. One New York gallery started to use the same boiler-room tactics that had been used to sell real estate and penny stocks. Center Art Galleries, Zabrin’s big Hawaiian client, was slicker but just as relentless, providing constant updates about the supposedly escalating values of prints and reminders that the decrepit master Dali was at death’s door (he finally did die in 1989).

It was one thing for an art lover to frame a print, hang it on the wall, and brag about the artist’s signature. It was quite another thing for an art investor to leave the print in the shipping tube and store it in a safe place like a savings bond, waiting for it to appreciate. When those buyers discovered the true value of their investment, they were not just disappointed. They felt robbed. Some sued galleries. Others complained to the Federal Trade Commission. Since the offers and often the prints were sent through the mail, postal inspectors led the investigations, and in 1987, with warrants from the U.S. attorney, the feds raided Center Art Galleries in Hawaii and seized all the Dali prints.

Photograph: Courtesy of Ricki Zabrin

An honest deal: In 1989, Zabrin suggested to LeRoy Neiman that he celebrate Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls with a limited edition print; the artist finished the piece in 1991.

For Michael Zabrin, the federal investigations still seemed as far removed as the 50th state. He was getting increased requests for certificates of authenticity, so he created his own form, bearing the name Michael Zabrin Fine Arts, which he would stamp with a notary-style seal to make it look more official. But behind the scenes, the real value of the prints was something he joked about with the gallery owners. “I would sell a hundred Picassos for $10,000 each,” he recalls, “and sometimes on the invoice I would write, ‘One hundred pieces of shit.’”

A greater concern would be the health of Leon Amiel. Rumors about a serious illness proved true when he died from liver cancer in October 1988 at the age of 67.

Hilda and her daughters, Kathryn and Joanne, took control of the business, moving most operations to an old Long Island carpet factory near their home. No doubt sensitive to all the investigations involving Amiel prints, they changed the name of the business to Original Artworks and made the Long Island dealer Coffaro their biggest distributor.

Even though his pipeline to the master prints was now rerouted back through Coffaro, Zabrin still had a galaxy of connections in the gallery universe to help him diversify. He says that at least half of the art he sold was legitimate. He was a flamboyant fixture at Artexpo in New York, sometimes making as much as $50,000 in a week but also staying on the lookout for up-and-coming artists he could represent. He met luminaries such as Peter Max, the longhaired pied piper of hippie Day-Glo poster art. Ricki recalls that Max would summon Zabrin to his home on Riverside Drive in Manhattan, doodle on a piece of paper, and ask, “How much would you give me for this?” When Max set up these meetings, Ricki says, “he would tell Michael to bring plenty of cash.” Zabrin tried to leverage the doodle sprees into a limited print deal. When Max backed out at the last minute and took the idea to a major publisher, Zabrin recovered some of his expenses through a lawsuit. (In 1997, Max pleaded guilty for not paying taxes on art sales of $1.1 million and was sentenced to community service.)

Zabrin was much more successful with his courtship of LeRoy Neiman, whose confetti-style oil paintings brightened the pages of Sports Illustrated and Playboy. They met through a casino pit boss, but Zabrin quickly proved his value to Neiman by getting him good prices from galleries for his magazine sketches and cutouts. One night in 1989, as Michael Jordan fever was burning through the sports world, Zabrin turned on the TV to watch a Chicago Bulls basketball game. The camera caught Neiman, with his outlandishly long twirled mustache, sketching from the sidelines. The next day, Zabrin called Neiman to propose a limited edition print of a Jordan painting that would be autographed by both the artist and the basketball star, with Jordan’s proceeds going to his charitable foundation. For Zabrin, Michael Jordan had opened the door to an entirely legit enterprise that melded art with collectible memorabilia. He teed up the Chicago Bears’ legendary running back, Walter Payton, as his sequel.

One afternoon in October 1990, with all of these new opportunities swirling around him, Zabrin was wakened from a nap. He heard the doorbell and then the anguished cries of his housekeeper. He jumped out of bed and looked outside to see his townhouse surrounded by men in blue windbreakers. Already some were trooping through his dining room and down into his sunken living room, where framed art hung from the walls as if in a gallery. At first, still half-asleep, he had no idea what they wanted. But when he went downstairs, an assistant U.S. attorney and a postal inspector pushed forward with credentials to identify themselves. It was a raid, and Zabrin could only think, “I’m screwed.”

* * *

When complaints to the FTC about fraudulent art continued to mount during the late eighties, much of the federal criminal investigation fell to Jack Ellis, a postal inspector based in New York City, where the first print boiler-room cases were prosecuted. Ellis would eventually dub his probe Operation Bogart, as in “bogus art.” “I felt that the only way we could get ahead of the crime was to find the source,” Ellis says, “and I realized pretty quickly that Leon Amiel was the biggest player.” After Amiel died in 1988, Ellis says, “we figured his business would die with him.”

Instead, the Amiel presses—under the more reckless management of Amiel’s widow and daughters—would find another life. Prints that the dead patriarch may have withheld because of shoddy work-manship or amateurish signatures were flushed through the network. Worse yet, from Ellis’s perspective, by filtering orders through Coffaro, Hilda and her daughters “were even more insulated from the trade than Leon.”

As the postal inspectors assembled lists of all the galleries with suspect Amiel prints, there was one other common thread—a dealer who appeared to be the biggest nationwide distributor: Michael Zabrin.

In 1990, Ellis enlisted his counterpart in the Midwest, Jim Tendick, to check out Zabrin and orchestrate a sting. Tendick had a female undercover agent call Zabrin to set up an appointment. Zabrin first met her in Washington, D.C., and then she came to see him in Northbrook. He remembers that she bought $17,000 in prints and later $10,000 more.

Tendick says that his agent selected only titles “that we knew to be high-quality fakes.” When she requested certificates of authenticity, Zabrin dutifully provided the ones with the Michael Zabrin Fine Arts stamp.

During the raid at Zabrin’s house, as agents rifled through the hanging art racks and dozens of flat file drawers in basement print rooms, the assistant U.S. attorney took Zabrin aside to serve the warrant. Soon after, Tendick arrived to talk some sense. He recalls that the prosecutor told Zabrin, “Now’s your chance to buy a ticket for the train or watch it leave the station.” Zabrin quickly agreed to help them, but Tendick warned him, “You have to keep your mouth shut. If people know you’re cooperating in a criminal investigation, you’re of no use to us.”

But in the beginning, even if Zabrin did stay undercover, Tendick wondered how useful he could be. “He was hard to control; very goofy and childish.” He could dissolve into giggle fits when he was strapped to the body wire or when a phone tap clicked on. Then he had trouble concentrating on his talking points, Tendick says, “like a little kid who wants to go play with his toys.”

There could be no margin for error with Zabrin’s targets—especially Phil Coffaro, whom the inspectors already knew to be as slick and slippery as Leon Amiel. They needed unequivocal proof that Coffaro realized that fake Amiel prints were being sold as though they were authentic.

To Tendick’s surprise, Coffaro and everyone else who spoke to Zabrin were disarmed by his goofy behavior. During one recorded call with Zabrin, Coffaro revealed why Amiel had stored his fakes without signatures—in case his warehouse was raided. On another taped call, Coffaro commiserated with Zabrin about the declining quality of Amiel prints since Amiel’s death. He told Zabrin that after he had rejected one batch, Amiel’s daughter Kathryn replied, “Look, I know the [prints] are terrible. My mother had my uncle signing them, but Sarina [Kathryn’s daughter] will be coming home soon [from college], and they will be better.”

In July 1991, postal inspectors in New York simultaneously raided Coffaro’s gallery and frame shop and the Amiels’ facilities. Coffaro quickly understood how much he had been incriminated during the Zabrin calls and meetings, so he, too, offered full cooperation. Almost immediately the inspectors went to work sorting through the Amiels’ old carpet factory, where they ultimately tallied 50,000 fake Dali prints, 20,000 Mirós, 2,200 Picassos, and 650 Chagalls. The authorities also seized from the women more than $4 million in cash, bank accounts, real estate, and luxury cars.

When New York’s chief postal inspector held a press conference about the haul, he proclaimed, “We believe this has cut off the single largest source of counterfeit prints of famous artists.” Although Hilda would die from cancer before the charges came to trial nearly three years later, her daughters and granddaughter would be convicted. Kathryn was sentenced to 78 months, Joanne to 46, and Sarina to 33. Besides testifying against the Amiels, Zabrin was a key witness in the trials of several gallery owners, including Chicago’s Donald Austin, a former barber who had two galleries on the Magnificent Mile and 28 other locations across the country. He was convicted in 1994 and sentenced to nearly nine years.

“It’s no exaggeration to say that Michael was the linchpin for Operation Bogart and all the convictions that resulted from that,” says Tendick. “And because he helped us, we helped him.”

Zabrin pleaded guilty to just two counts of mail fraud in 1985—his earliest documented offense. In return, in January 1994, the judge sentenced him to a year and a day in prison; a relative slap on the wrist compared with the punishment meted out to Austin and the Amiels.

In April 1994, Zabrin was sent to serve his sentence at a low-security prison camp in Marion, Illinois, six hours from home. “At first, I was scared shitless,” he remembers. “I had no idea what to expect, but after I got acclimated and realized I could get along with everybody, it actually turned out to be fun. It was like a camp for bad boys.”

In only ten months, camp was over, and he was placed in a downtown Chicago halfway house, 30 minutes from home. Except for the pain of being separated from his wife and two daughters, who were then in the first and third grades, it had been almost too easy, he now admits.

As for his future livelihood, he felt that there was no other choice. “I went back to selling art,” he says. “It was the only thing I knew how to do. But I wasn’t going to have anything to do with any forgeries or any pieces that were phony.”

However, Zabrin quickly realized that the only dependable business for him lay with the master prints, because, he explains, “that’s where the money was.” Despite his incarceration, his network of gallery contacts remained intact. And despite all the bad press, galleries still pestered him for prints.

Photograph: Courtesy of Ricki Zabrin

A counterfeit Roy Lichtenstein

By the early 2000s, powerful new ways had evolved to sell the old masters. Zabrin was introduced to these advances by a client who had previously sold art only at auctions. “All of a sudden,” Zabrin remembers, “he was selling a lot of pieces without doing a lot of work.” The reason was eBay—an auction to the world that could be run out of your garage.

As Zabrin visited the client to deliver merchandise, he got to know the computer geek behind the sudden success, who we will call “Brian” (he has yet to be charged for any related offenses). Besides setting up auctions on eBay, Brian had also built a website for the client. Since Zabrin seemed to be the man with the goods, Brian approached him with a deal. “He told me he was thinking of leaving and that he could do the same type of business for me,” Zabrin remembers. “He thought we could make a lot of money together.”

Before long, Brian was camped out with his laptop and PCs in the bedroom of the Zabrins’ daughter who had gone off to college. Zabrin came up with the site’s name—FineArtsMasters.com—and his partner did the rest: posting the auctions on eBay and listing the prints on the new website.

Zabrin stood back and waited for the geyser to blow. Soon dollars—in the hundreds of thousands—were gushing into his PayPal account. Some days Brian, who packed the prints at the dining table, could not handle the orders on his own. Zabrin had to rush to the rescue with armfuls of shipping tubes and rolls of labels—all to keep timely delivery and their precious five-star rating on eBay.

Fueling the sales surge was the best source Zabrin had ever found, an Italian dealer named Elio Bonfiglioli. A Chicago gallery owner had been the first to call Zabrin about Bonfiglioli, who had sold him what looked to be an authentic Miró at a fantastically low price. Zabrin tracked Bonfiglioli down in Italy, and two weeks later the dealer was on a plane to Chicago. “We hit it off instantly,” Zabrin says.

Bonfiglioli looked and acted like Roberto Benigni, the Italian movie star who had won an Oscar a few years earlier for his role in Life Is Beautiful. Zabrin had finally met his clownish match. “Elio spoke in broken English that was so funny,” Ricki says, “we would all start to laugh before he opened his mouth.”

But there was nothing funny about his prints. “They were so good, at first I thought they were real,” Zabrin says. “But he started making little remarks like, ‘All prints are fake.’ Then, as I got to deal with him more, I would get better prices for buying more, which meant he was getting them made.” Eventually Zabrin discovered that Bonfiglioli’s forgeries were created by experienced printmakers in Italy and Spain.

Despite his growing sales and the impeccable merchandise, Zabrin knew that there really was such a thing as too much success—especially if it attracted attention from the authorities. He had to keep the lid on and run the website and eBay auctions like a cottage industry.

But Brian was not content with a cottage. Now sophisticated in the world of unlimited edition prints, he wanted a space in River North near all the other galleries. And Zabrin, still unsophisticated about computers, could do little to stop him.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, another name would suddenly blast in from the past—Leon Amiel. Not the dead patriarch, but Leon Jr., son of Kathryn and brother of Sarina. Unlike them, he had not been involved enough in the counterfeiting operation to go to prison. But now he was knee-deep in the business, attempting to market a hidden stash of the old man’s best masters.

Amiel first contacted Zabrin through instant messaging. “I would get messages from someone claiming to be Jason,” Zabrin recalls. “He was supposed to be an assistant working for Leon Amiel. He would say that Leon was out of the office playing cards, and although Leon didn’t want to deal with me, Jason would.” All the time, Zabrin knew it was really Leon sending the messages.

Against his better judgment, Zabrin put through some orders for Chagall prints, which had been particularly hard to find after the demise of Leon Sr. and the arrest of his widow and daughters. More orders followed for other artists as well.

What Zabrin didn’t know was that Amiel had been suspended by eBay because of complaints from his buyers, and while he depended on Zabrin and other dealers to post his prints on consignment, he continued to flout the site’s rules by putting in phony bids to inflate the prices.

All of this fraudulent activity had not gone unnoticed by either eBay or the feds. Since computer scams are considered wire fraud, the first investigations were conducted by the FBI. But because most eBay sellers ship prints through the mail, postal inspectors were brought in as well.

John Donnelly was the Chicago postal inspector assigned to the case in 2006, long after Jim Tendick had left the city. Coincidentally, in his previous job, Donnelly had been a probation officer for Donald Austin, the Chicago gallery owner the feds had convicted thanks to Zabrin’s testimony. For Donnelly, the names bubbling up to the surface with the eBay complaints sounded very familiar—especially the man in the middle of all the action.

On the morning of May 6, 2006, federal agents massed again outside Zabrin’s Northbrook home. This time, their appearance did not shock him. In fact, he says, he was expecting it. “Different people told me that postal inspectors had interviewed them about my packages and asked what kind of person I was,” Zabrin recalls. “I knew it was a matter of time.”

First came the warrants, then a lecture from the assistant U.S. attorney and the request for cooperation. “Zabrin knew the drill,” Donnelly says, “and he was ready to do what was necessary to reduce his sentence.”

But even though Zabrin professed his willingness to help, Donnelly had no idea just how helpful he would be. “When we had him wired up,” Donnelly says, “it was like we had a perfectly programmed robot. He understood the elements of the crime and exactly what we needed to prove that the targets knew they were selling fakes.”

To incriminate Amiel, Zabrin simply had to take his phone calls. “Zabrin knew how much Leon loved to gossip,” Donnelly says. “They would just go on and on about everyone else’s business and all the stuff they were selling to them.” (In October 2010, Amiel pleaded guilty to one count of mail fraud and was sentenced last June to two years.)

With the advances in surveillance technology, Zabrin could also be wired for video. “The camera lens was so tiny, it could film through my buttonhole,” he says. He wore the camera when he moved among the booths at Artexpo, where he recorded an Amiel associate describing his methods for copying Picasso prints and how they “looked so good.”

Zabrin claims he also wore a wire during a conversation with the Chicago gallery owner Alan Kass but says this brought him no satisfaction. “It felt shitty,” he says. Their friendship went back to the eighties. Kass/Meridian—with the gallery’s banner fluttering above the restaurant Nacional 27, at Huron and Orleans Streets—had become a landmark on the River North art scene. Kass sold the work of living artists, but from the beginning he had made Zabrin’s master prints a staple of the business. (At presstime, Kass has plead not guilty to knowingly selling fakes and is preparing for trial.)

Zabrin had fewer reservations about stinging James Kennedy, a virtual caricature of the dealer con artist. A bowling ball of a man, Kennedy had beady blue eyes and long blond hair that he wore in a mullet. According to court documents, he partied hard, with alcohol and drugs, and although married, boasted in graphic detail about his sexual conquests, claiming that he had acquired original Picasso drawings (all fakes) after he had an affair with the master’s daughter Paloma.

“In the beginning,” Zabrin says, “he was fun and outgoing, but the drugs made him too outgoing.” Kennedy was brazen about his forgery. He would buy prints from Amiel and add the signature himself. He was so proud of his handiwork that he burst into the Zabrins’ living room one afternoon while Zabrin was with Brian during the early days of the website. As Zabrin recalls, Kennedy held up a print and proclaimed, “Here’s the latest and the fakest.”

Zabrin angrily pulled him from the room. “Shut up,” he hissed. “[Brian] doesn’t know about this.” But soon after, in a crowded designer frame shop, Zabrin watched Kennedy forge a signature with a flourish.

Once wired by the feds, Zabrin would meet for coffee with Kennedy, who needed little prompting to talk about his crimes. Often they got together in a Starbucks in Deerfield. Even in those cramped confines, Kennedy had no hesitation about whipping out his pen to lay down a forged signature—right in view of Zabrin’s buttonhole camera.

Eventually Kennedy’s behavior became more manic, and Zabrin wondered how he would react when the feds finally lowered the boom. “He thought he could get away with it. He was so coked up and crazy, he was like a time bomb ready to explode.”

Photograph: Candice C. Cusic/Chicago Tribune

Seized: In 2008, a federal agent handles a fake Dali print in the aftermath of a sting that relied heavily on Zabrin to implicate a second generation of suppliers and galleries

The explosion finally came on January 8, 2008, when Kennedy left a message on Zabrin’s voice mail. A few days earlier, Donnelly had confronted Kennedy and his lawyer with Zabrin’s audio and video recordings. “I thought you were my friend,” Kennedy’s message began. “You’re a dirty, lousy, no-good, cock-sucking, jagoff bastard. . . . They told me everything you done. I heard it, and I didn’t believe it. . . . And if I see you, I’m going to beat the living piss out of you, you jagoff prick.”

Zabrin forwarded the threat to Donnelly, who filed a federal complaint the next day against Kennedy for retaliating against a witness. Kennedy was arrested and locked up. Two months later, he was released, wearing an electronic monitoring device. In October 2008, he tore that off and fled the country—first heading to Canada, where he was turned away at the border, and then to Mexico, where he was nabbed two months later. (At presstime, Kennedy, who has pleaded guilty to wire fraud, mail fraud, and threatening a witness, still awaits sentencing.)

But for Donnelly, Kennedy was not the only threat to the art fraud investigation. The other was Michael Zabrin. As the postal inspector soon discovered, selling counterfeit art was not Zabrin’s only crime. He was also a serial shoplifter—of high-priced merchandise (designer handbags, crystal) at the finest stores (Neiman Marcus, Saks, Barneys) and at the worst possible times. Once he was nabbed just before he was to meet Donnelly and other investigators, following the 2006 raid on his house.

Zabrin makes no excuses for the shoplifting other than to say, “I never sold [anything] or made money off of it.”

His wife attributes the kleptomania to his “goofy” upbringing by a mother who, despite her wealth, was also caught shoplifting. “It’s something he does when he gets anxious,” Ricki explains.

She speaks with the insight of the many mental health professionals who have diagnosed Zabrin, according to court records, with “depression, generalized anxiety, a severe obsessive-compulsive disorder [and] a variety of related impulse control disorders,” all of which led him to addictive behavior.

Although the mental issues shadowed Zabrin from the start of their relationship, Ricki believes his depression surfaced after his first incarceration, when he realized that print fraud was the only way he could make a good living. In 2004, he attempted suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills, and thereafter he remained heavily medicated.

His anxiety was only exacerbated by his second arrest, his return to the role of secret informant, and the fear that he would be discovered. Financial stress made matters worse. Prohibited by the agents from selling fraudulent art prints and desperate to stave off foreclosure on his house, Zabrin tried another gambit. Using funds from an old partner, he purchased eight Chagall prints. But he then kept two for himself and told the partner that he had bought only six. He sold those two and pocketed the cash. Zabrin was convinced that the prints were authentic and paid accordingly. But the prints turned out to be fakes, and the whole scheme unraveled when Zabrin’s partner complained to Donnelly.

“It was bad enough that he tried to sell the art behind my back and cheat his partner,” Donnelly says. “But the fact that it was fraudulent art was even worse.” As a result, in June 2007, Donnelly had to swear out another complaint against Zabrin. His usefulness as a government witness had effectively come to an end, along with his protection against the state shoplifting charges. He received three years for retail theft and started serving in January 2009.

* * *

Of all the masters he sold, Michael Zabrin most appreciated the subtle genius of Joan Miró. For the uninitiated, Miró’s work appears to be the scattered splotches and disjointed lines that a child would make with a paintbrush. But look a little closer at the black bean shape in the center of La Femme aux Bijoux, a Zabrin favorite. Those bright colored spots could be the makeup on a dancing girl’s face; the ragged wishbone shape to each side could be the leg that she kicks up and holds aloft.

A judge or probation officer would need similar powers of artistic interpretation for a sympathetic reading of Zabrin’s criminal record. Otherwise the sheer number of cited incidents adds up to an ominous mass—especially in the unforgiving light of federal sentencing guidelines. A “life of crime” is how the assistant U.S. attorney put it in one court document.

Zabrin’s lawyer, Jeffrey Steinback, made an eloquent appeal for another view of his client when Zabrin was sentenced last June after pleading guilty to three counts of mail fraud. Zabrin, Steinback said during the hearing, was not a violent or greedy man. If anything, he was too sensitive to others’ needs and too generous in return. It was not just Zabrin’s myriad addictions that the court should consider, he argued, but an art industry still dependent on master prints.

But the judge chose to see the picture painted by the prosecution. When he pronounced the sentence of nine years and two months—which can be reduced to seven years with good behavior—a collective gasp went through the courtroom. Some law enforcement officials later told Ricki that they were as shocked by the sentence as she was.

While Ricki appreciated the sympathy, she couldn’t help but feel bitter. “The government would never have [prosecuted] the number of cases it did without him,” she says. “It didn’t matter that he couldn’t testify. Because his wire evidence was so strong, the targets all took guilty pleas.”

She is equally angry about all the dealers and gallery owners who profited from fraudulent prints and were never charged. “Michael absolutely took the fall,” she says. “He became the biggest scapegoat in the industry.”

Today, she still lives in the Northbrook house with one of her two daughters, holding down three jobs to pay the bills. Framed art continues to crowd the walls, all of it modern, but there are also life-size, lifelike plaster sculptures of a butler and a waitress, funky metal dogs, collectible cartoon figures, and intricate cityscape cutouts. In its eccentricity and eclecticism, the collection hovers around Ricki with Zabrin’s nervous presence. Sometimes, when she’s not feeling angry, she flips through photos from the old days, looking at some of the same people she now regrets that her husband ever met. “He used to be so much fun,” Ricki says. “I think about those times and I laugh so hard. But then I cry.”

Photograph: Candice C. Cusic/Chicago Tribune