You have never seen someone make phone calls like Law Roach makes phone calls. In the back of a black Escalade crawling through Midtown Manhattan traffic to the Tommy Hilfiger offices, Roach has dual iPhone Xs pressed symmetrically to each cheekbone, shifting between conversations with no discernible warning. On both phones, a second caller is on hold — a frazzled assistant in L.A., a promoter begging him to bring Zendaya to one event or another. Which is to say, Roach is conducting four phone conversations at once, a feat that is giving me no small amount of secondhand anxiety. This is normal, he assures me.

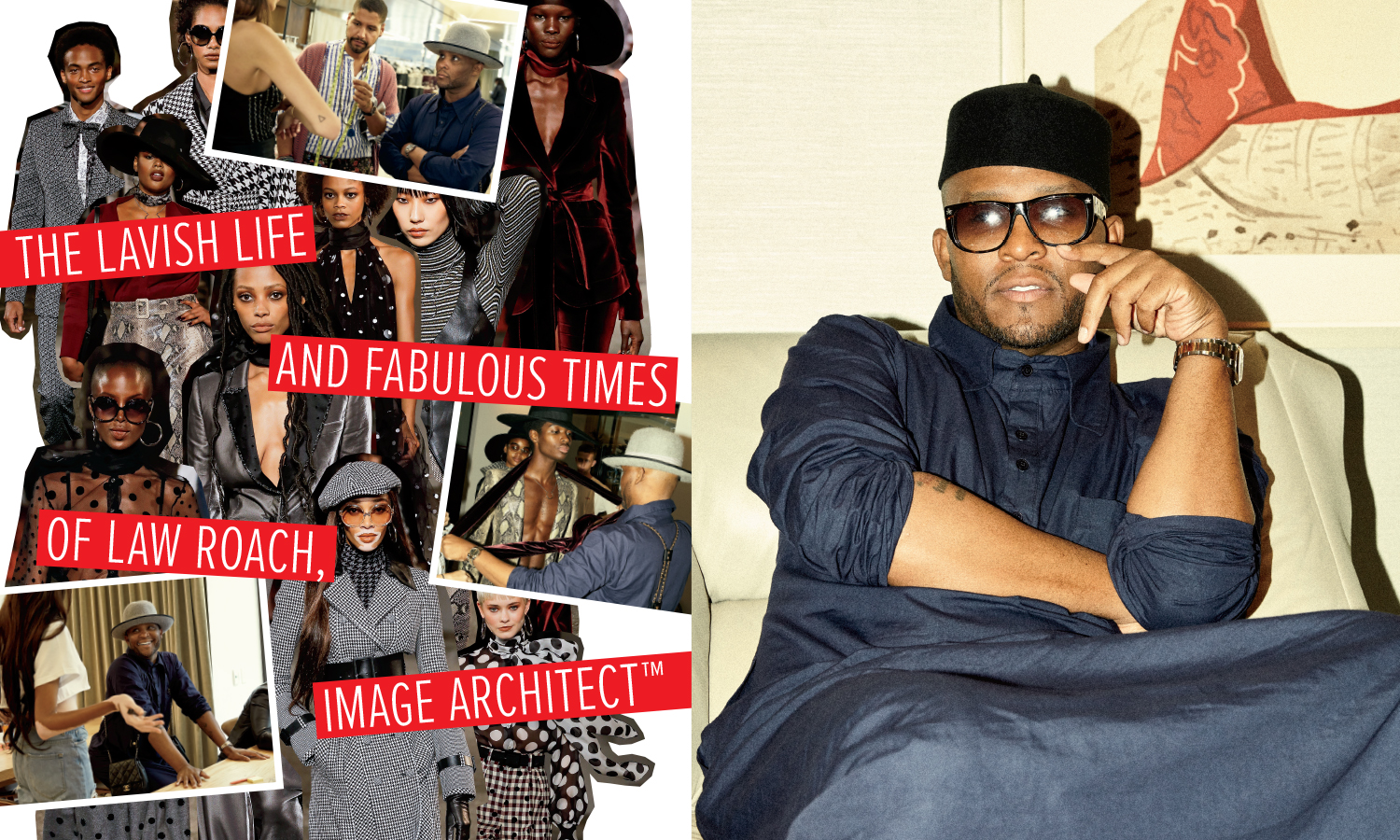

Or at least this is normal when it’s two days before New York Fashion Week and you’re arguably the world’s most in-demand celebrity stylist. Except that Roach doesn’t like being called a stylist: It’s a little bit basic, the kind of term claimed by people who list four different cities in their Instagram bio. He prefers — insists upon, really — the title of “image architect,” which he says he trademarked a couple of years back. (How’d he go about registering the trademark? “Being a cunt,” he says with a little sideways laugh. “I get so much joy out of sending cease-and-desist letters.”) “Stylist” would suggest that Roach’s job is to put beautiful clothes on beautiful people, and on some level this is the case. But what Roach does isn’t really about fashion per se; fashion can be bought, learned. There is a cerebral side to image architecture, as he tells it, a way of approaching each client with the holistic, methodical detail of an architect drafting a blueprint.

And then there’s something else, too: the unquantifiable part of the whole Law Roach thing that can’t be taught or faked. He’ll tell you it’s simple. It’s just that Roach loves women more than anything — loves the idea of them, the glamour of them, has since he was a kid growing up on Chicago’s South Side. And when Roach goes about dressing a woman, there is an element of divination to the process. He sees them, simple as that.

A month after our meeting, at the 2019 InStyle Awards ceremony, Roach will receive his Stylist of the Year honors from Zendaya, the mind-bendingly gorgeous young actress who, beyond being Roach’s longest-running client, has become his muse, his little sister. “You are an absolute visionary,” she’ll gush as Roach takes the stage, swathed in the silken robe of a Qing dynasty emperor at the height of his power. “You have taught me so much about myself: not to give an ef what people think, to be proud of who I am when I look in the mirror.” What Roach does for his clients is deeper than putting them in clothes.

The visit to Tommy is to wrap up the many loose ends of this weekend’s runway show for the latest Tommy x Zendaya collection, for which Roach, 43, serves as creative director. This is one of his roughly 40 gigs, the most prominent including a stint as a judge on America’s Next Top Model, a mentorship position at cooler-than-thou streetwear platform VFiles, and a client roster boasting, either currently or at one point, Céline Dion, Ariana Grande, Mary J. Blige, Tiffany Haddish, Anne Hathaway, Tom Holland, shall we go on?

You probably want to know what the world’s sole image architect is wearing two days before fashion week. Today, Roach is dressed in a thawb, an ankle-length tunic popular in the Arabian Peninsula — it’s kind of his thing at the moment — styled with a thrifted navy blazer, gold-framed Gaultier eyeglasses, and a jaunty black felt fez, or something fez-adjacent. He is wearing androgynous stack-heeled white boots by Maison Margiela whose cloven-toed design, inspired by Japanese work boots of the early 1900s, is more Tatooine cantina than Vibram FiveFingers. Roach left Chicago for Los Angeles almost six years ago, but two faded tattoos scrawl down the sides of his supremely moisturized fingers: One reads “312,” the other “Fuck You.” “Kinda like, ‘Fuck you, I’m from Chicago, I don’t care,’ ” he says with a sly grin.

And he is carting around an Hermès leather purse, the size of an extra-large pizza box, that should probably be behind glass in a museum — an intricately stitched leather collage depicting a cool-toned, headlight-lit, mountainous highway scene. This bag is currently Roach’s most beloved possession, and when I tell you the retail cost, it’s going to make you feel something. I will put it like this: You could buy a gently used 2017 Mercedes-Benz E300 right now and still have 10 grand to play around with, or you could have this bag.

As for the doubles match of phone calls happening as our car creeps down Madison Avenue, Roach is in dire need of looks for two of his clients to wear at the Emmys in just a couple of weeks, one for Zendaya and one for his newest client, the British actress Jameela Jamil. “I need you to get to Vera Wang immediately,” he’s imploring his assistant in L.A., second phone showing sketches of the designer’s gowns in ice white and emerald.

Onscreen, these gowns don’t particularly move me in any special direction; they’re pretty, but then again, one would hope they’d be. Yet two weeks later, when my Twitter timeline floods itself with photographs of Zendaya on the Emmys red carpet, I’ll get it. To behold the 23-year-old Euphoria star in a custom silk gown somewhere between Batman & Robin’s Poison Ivy and The Wiz’s Emerald City, slit up to there, legs down to there, hair in auburn Old Hollywood waves, is just plainly one of those moments that somehow reaffirm our brief tenure on this burning planet. It reminds me of watching televised red carpets as a kid, not out of any real interest in the awards themselves but for the sheer awe of witnessing the spectacle of women’s magic, studying how surface details could occasionally reveal the soul. I suppose what I’m saying is, it’s art.

Law Roach was never supposed to be here, “here” being the ritziest echelons of red-carpet fashion or the Tommy Hilfiger showroom. He grew up moving around the South Side, mostly near 79th and Essex in South Shore, the oldest of five siblings with a single mother; his father was never in the picture. He went to Harlan Community Academy, off 95th and Michigan — when he felt like showing up. “There just really wasn’t any rules in my house when I was living with my mother,” he recalls. At 14, he moved in with a friend whose structured household Roach credits for helping him to finish high school. “My situation at home wasn’t the best,” he tells me. “I grew up in a tough neighborhood, in a school that was full of gangs. I don’t know what saved me. I just always knew something bigger was coming.”

Roach never had to officially come out as gay to his high school peers — it was something that was just kind of understood. “We’re talking about a time when being gay in the black community was really tough,” he says. “But I never really had a lot of problems, because I was always comfortable with being me. I’ve always had a soft voice, I’ve always had very feminine mannerisms, so it actually made me feel special, because I was so different from everyone around me.” Back then Roach hung out with the tough guys in school, who implicitly had his back. “I mean, you had the bullying. I got the ‘faggot’ every now and again. But I also had friends who were like, ‘Yo, what’d you just call him?’ I always felt really protected. My authenticity that helps me excel today — it helped me back then too, because I was just always me.”

Roach was obsessed from an early age with the iconography of women. His mother introduced him to the films of Diana Ross: Lady Sings the Blues, The Wiz, and especially Mahogany, the Motown-produced 1975 drama in which Ross plays a South Sider who works her way up from Marshall Field’s shop girl to the hyperglam world of European fashion. Ross designed all her own costumes for the movie, Roach tells me, the flowy peach silk kimonos and rainbow-colored dream gowns. “Making clothes for rich people to look at in a magazine? You think any of this crap means anything to these people around here?” a fellow South Sider barks at Ross’s character, who tosses back: “It means something to me!” In some circles, the film’s considered high camp; to Roach, the Midwestern tale of the transformative power of glamour was a revelation.

Meanwhile, Roach would accompany his grandmother thrifting after church each Sunday, despite the fact that showing up to public school rocking Salvation Army wasn’t a fast track to popularity in the ’80s and ’90s. “For young people, we wanted everything new and brand-name,” he explains. “But I wanted to have cool stuff that nobody else had, and I didn’t have a lot of money. Years later, I fell in love with the art of thrifting all over again. I think it’s an art form.”

When he got back into thrifting in his 20s, after studying psychology at Chicago State, Roach was initially shopping for himself but was increasingly drawn to the women’s pieces that gave him unexplainable chills — dresses and shoes and handbags that occasionally reminded him of people he loved. He’d start downtown and head toward the south suburbs, hitting all the Salvation Armys and Village Discount Outlets in between.

Still, it was a hobby, not a vocation. “I just didn’t grow up thinking that fashion was something you made a living doing,” he tells me. “I’m from the time where it was very much: Go to school, get a degree, get a good job. I didn’t have anybody to look up to in creative fields, to show that you can live in abundance doing creative things.”

Before long, Roach had built up a serious collection of women’s vintage, much of which he kept stashed in the trunk of his car. One night, after a bartending shift at the since-shuttered West Town club Rednofive, a friend happened to glimpse one of Roach’s hauls spilling out of his trunk. “There was this huge black leather clutch, and she was like, ‘Oh my God, why do you have that?’ ” he remembers. “She said, ‘How much would you charge for it?’ I was like, ‘Uh, maybe 50 bucks?’ And I had paid, like, $2 for it, so that markup was kinda incredible. She showed the bag to some of our other friends and told me, ‘Everyone wants you to come over. We’ll have cocktails. Just bring all your stuff.’ ” Suddenly Roach was doing regular trunk shows that were getting more and more popular, friends inviting friends inviting friends. The trunk of his car wasn’t cutting it anymore.

By 2009, Roach and a close friend, Siobhan Strong, had opened Deliciously Vintage, a storefront at Halsted and 18th in Pilsen. The two had known each other since the late ’90s and would collaborate on styling gigs around town, for which they accumulated a carefully curated collection of vintage pieces they’d alter to be more fashion-forward. In their four years in business, the duo developed a reputation for the illest secondhand finds in the city, a mixture of designer pieces and whatever else happened to catch their eye. They had a certain girl in mind. “Sometimes with fashion, everybody kinda looks the same,” Strong tells me by phone. “So people would come into Deliciously Vintage to get that great piece to set them apart. Maybe for their birthday they want a sequined jacket from Balmain from the ’80s, something that no one else is gonna look like that in that moment. It wasn’t for everyone. Chicago gets a bad rap because it’s the Midwest, so people think everything is utilitarian. But girls here get it.”

The store’s reputation spread by word of mouth (the social media era was only just beginning). But Roach and Strong’s social circle ran deep—and included Kanye West, whom Strong had known since college. And when West popped in unannounced in the spring of 2009 to drop five grand on clothes for someone TMZ called an “unnamed woman” (read: Amber Rose), the store blew up. Suddenly stylists were flocking in from across the country, soliciting Roach and Strong to help them find the gems. “Of course I knew what a stylist was, but I didn’t know how viable that profession was until then,” Roach recalls.

It was Kanye’s endorsement that emboldened Roach to establish himself as a professional artist. “You know, fake it till you make it, be confident while you faking it,” he says with a laugh. He won people’s trust through sheer charisma and kept their trust by making them look dope.

Roach’s first paying client was the R&B singer K. Michelle; around the same time, a family friend introduced him to then-14-year-old Zendaya, a mostly unknown Disney Channel actress who shopped predominantly at Target. “Z was more of a passion project,” he remembers. “We did one job, and we’ve just been together ever since.”

In 10 years, Roach has nudged the actress into her spot as a Gen Z style icon — scratch that, the Gen Z style icon, consistently the only real risk taker on any given red carpet best-dressed list. There was her jaw-dropping Joan of Arc look in straight-up Versace chain mail at the 2018 Met Gala; her transformation into a monarch butterfly at the Australian premiere for The Greatest Showman; the time, two days after my meeting with Roach, when she arrived at a Harper’s Bazaar fashion week party in the same dapper Berluti suit as Michael B. Jordan, outswaggering the Black Panther star. At last year’s camp-themed Met Gala, Zendaya’s teched-out Tommy Hilfiger ball gown lit up from gray to Cinderella blue with the swoosh of a wand by her date, Roach, her very own fairy godbrother. The effect was equal parts Disney princess and Blade Runner replicant, the ultimate allegory for the actress’s transition into her realest role yet — as Euphoria’s fresh-out-of-rehab Rue Bennett. That same night, Roach crowed to Vogue: “Next year we’re going to have to chill out or come down from a helicopter like Diana Ross at the Super Bowl.”

The Looks of Law

Roach dishes on some of his most buzzed-about stylings.

There’s a similar element of storytelling in his now-legendary 2016 transformation of Céline Dion, in the eyes of the public, from middle-aged Québécois chanteuse to one of the best-dressed women alive. It was a few weeks after hiring Roach — and a few months after the death of her husband, René Angélil — that Dion stepped out in Paris, aviators on, swimming in an oversize sweatshirt from the cool-kids brand Vetements, Jack and Rose superimposed over an image of the sinking Titanic. On one level, it was simply cool as fuck: Dion cheekily nodding to her own performance of the theme song of the James Cameron film, doing streetwear better than any of The Youth. But there was also something intimate going on there, a tenderness to the allusion to “My Heart Will Go On,” about seeking a little joy in the face of grief. It was probably the most endearing moment in 2016 fashion, all thanks to a hoodie, jeans, and Roach’s vision.

Still, Roach rejects the idea that he in any way transformed Dion — he simply presented the Dion who had always been there, who just hadn’t been caught in the right light yet. “Never,” he emphasizes when I ask if he’s ever attempted to completely reinvent a client’s image. “That’s why I get so happy when people tell me that all my clients look so different. They all have their own personality, their own DNA, and that’s because we work hard to keep it authentically them.”

Same principle goes for his work with Ariana Grande, whose four-plus years as Roach’s client have coincided with her evolution from precocious Nickelodeon alumna to stratospheric pop icon. After meeting Grande in 2015 through her publicist, whom she shares with Zendaya, Roach knew he wanted to preserve the pop star’s signature touchstones — the high pony, the thigh-high boots, the Playboy bunny ears — but to elevate them. Hence, the dress inspired by the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel that Grande wore to her first Met Gala in 2018; the bondage-informed patent leather and hardware of her 2019 Sweetener world tour; the cloud-colored custom Zac Posen gown she flexed on Instagram while ditching the 2019 Grammys, all over a beef with the awards show’s producer, whom she accused of creatively stifling her scheduled performance. (She won her first Grammy that night anyway.) Roach’s only rule for designers he might commission to dress Grande: They have to like her music. Otherwise, what’s the point?

It may have been Céline’s sweatshirt moment that caught the attention of Tyra Banks and her America’s Next Top Model coproducers, who in 2016 hired Roach as a member of the show’s ever-contentious judging panel. Almost immediately Roach became the hook of the mostly Tyra-less 23rd season (hosted that year by Rita Ora), with his glossy, Cher-length wig and a mix of shade and tough love. “Above the waist, you’re a supermodel. Below the waist, you’re supermarket,” he told one contestant of her tragic gladiator sandals.

It was pretty clear when Roach felt compassion toward a particular model-in-training, occasionally to the point where elimination panels would devolve into shouting matches. “I have been told that I am an extreme empath — I connect to people in a really weird way, like, spiritually,” he tells me of his two seasons with the series. “So there was this one girl on the show I was really connected to, and when we sent her home, it was kinda hard. And then some of those girls, I was just like, ‘Ooh, girl, who cares.’ ” Kyla Coleman, the biracial model and staunch political activist who won the show’s final season, will be walking the Tommy x Zendaya runway.

We are just slightly late for the last runway-show model casting when we pull up to the Tommy offices. Roach spots one of his impossibly fly-looking assistants in the midst of a heated phone call outside the lobby, his Adidas track pants paired with dapper dress shoes. “Who’s he cussing out?” Roach wonders. It’s just some family shit, the assistant sighs as the elevator takes us up. “Oh, we hate families,” Roach deadpans with a twisted giggle. He glides into the buzzing showroom — thawb flowing, Benz-as-handbag in ever-so-casual tow — where I sense a slight but immediate shift in the space’s gravitational force.

Everyone in the Tommy x Zendaya fashion week war room is huddled around a dry erase board covered in headshots of the supernaturally hot, the runway model version of a criminal investigation board. An adjoining room, decorated inexplicably in the style of a ’50s diner, offers the most bougie corporate breakfast spread I’ve ever seen. Among the 20 or so Tommy staff members swarming throughout the glaring white space, a perplexing number seem to speak in the clipped mid-Atlantic accent of a character in a Hitchcock film, though this could easily be a side effect of my own anxious delirium, as I’ve arrived in fashion week’s preppy underbelly dressed more or less like Johnny Cash. An army of thigh-high snakeskin boots in hues of maroon and pale green lines the showroom walls to vaguely menacing effect.

Determining who will walk in Sunday’s show, and in what, Roach moves photographs from the “no” side to the “yes” side like a chess master playing against the computer. “I discovered this guy!” he announces, nodding toward a male model’s photo. “For real — he was my nurse. He was doing my bloodwork. I was like, ‘Don’t take this the wrong way, but you should be a model.’ He was like, ‘I’m studying to find a cure for sickle cell.’ I was like, ‘Nah, you should be a model.’ ” And so it was!

Hunched at the periphery of it all is one of the most beautiful human beings on the planet. Swallowed by a gray hoodie (hood up), baggy jeans, and black Chuck Taylors, Zendaya appears practically indistinguishable from her grungy Euphoria alter ego. She’s easily the chillest person in the room. “I can’t wait till I get back home so I can get a pottery wheel,” she mutters offhandedly during a break in the casting, telling Roach about her latest creative pursuit. “You’re so good at everything, Zendaya,” he lovingly chirps back.

The two settle in to finalize the music for Sunday’s show, which, under Roach’s direction, is being presented at the Apollo Theater as an ode to ’70s black culture that will refashion the runway as a block party. “I want it to have feeling, I want it to be emotional, I want people to feel something — the way we feel something,” Roach stresses, blasting Curtis Mayfield’s “Move On Up” into William DeVaughn’s “Be Thankful for What You Got” (you know, the “diamond in the back” song, the one that goes: “Though you may not drive a great big Cadillac, gangsta whitewalls, TV antennas in the back / You may not have a car at all, but remember, brothers and sisters, you can still stand tall.”) This, Roach insists, will be the centerpiece of the soundtrack: “Every black person in the world knows that song.”

This is the second Tommy x Zendaya collection for which Roach has served as creative director, which means he does it all: concept, casting, makeup, music, location. The first collaboration made headlines when it debuted in Paris last spring — a similarly ’70s-inspired ensemble that flooded the runway of the Comédie & Studio des Champs-Élysées with 52 black models of all sizes and ages, including Beverly Johnson, the first black model to grace the cover of American Vogue in 1974, and surprise show closer Grace Jones. Roach is relaying the show from the back of yet another black car, taking a break from runway show prep to check in to his mentoring gig at the VFiles showroom, the post-postmodern hub for aspiring young designers.

“If someone gives me that type of opportunity, I’mma go 110 percent,” he says, speaking of his exhaustive efforts with both Tommy collections. “And sometimes I give too much of myself. But I believe that when I come in and do that, it shows them …” He trails off for a moment. “Tommy Hilfiger has never worked with anybody that looks like me in that capacity. I mean, you were in the room — you saw how many black people there was!” (That would be four: Roach, Roach’s two assistants, and Zendaya.)

“Fashion is a very cliquey industry: The same people get the same opportunities over and over again, and then the people who worked for those people get those opportunities next,” Roach goes on. “It’s systematic in that way. And you have to be able to afford to work for somebody for free for two years to become the assistant.” Roach was the exception. “I just couldn’t have done it.”

He interrupts himself to handle a Jameela Jamil emergency: She’s DJ’ing Elle’s Women in Hollywood party and needs to wear something that says “cool DJ.” Roach is thinking something from Rihanna’s Fenty line, maybe some kind of swagged-out suit.

The Jameela situation handled, he’s back on track. “My honest opinion: I don’t think that everything is racist. I don’t think we are denied opportunities because of — well, no, a lot of it is fucking racism,” he says with a wry laugh. “But people like to work with people they’re comfortable with, right? With those who are familiar to them? It’s sad that we as black people have to work to make people feel comfortable, but that’s why we need to fight to make sure that landscape changes.” Recently, Roach tells me, he was misidentified as his white assistant’s assistant. He wasn’t offended, exactly, but he knew the score. “I just think [the woman] had never seen a black person in that position and automatically assumed it was the white person in the position of power. She had never experienced a” — he pauses, searching for the right word — “me before.”

Roach’s personal favorite look for Zendaya was her breathtaking appearance at the 2015 Oscars, the first time I can recall thinking about the actress as a bona fide star: ivory waterfall of a Vivienne Westwood gown, faux dreadlocks down to her waist. I hadn’t watched the awards show, but I’d definitely heard about the controversy surrounding it. On an episode of the E!’s Fashion Police, host Giuliana Rancic quipped that Zendaya probably smelled like “patchouli oil or weed.” Zendaya tweeted about the incident later that night: “My wearing my hair in locs on an Oscar red carpet was to showcase them in a positive light, to remind people of color that our hair is good enough.” Rancic backtracked an apology, throwing around words like “bohemian.”

At the time, Roach felt naturally protective of Zendaya, then only 19. “But what it did was start a conversation about black women’s hair and what was considered appropriate,” he says, proud in a tired way. “There are places where women can’t wear braids or Afros or dreads to work — schools, too. I think that gave women courage to say, ‘Fuck you, I’mma wear my hair how I want!’ So for me, that’ll always be an accomplishment. Even though it came out of a whole bunch of bullshit, it was a sacrifice for something major.”

Back in 2017, when Roach graced the cover of the Hollywood Reporter’s annual “Stylists & Stars” issue, flanked by Zendaya and Dion, he was the first-ever black stylist to do so. I wonder out loud whether anything’s changed since the cover was published. “I do think it’s changing, but what I fear …” Roach deliberates for a bit. “Being inclusive and diverse, in terms of size and race, is very popular right now. But I also think it’s very corporate; they do it because they know they’re supposed to do it. And I’m afraid when the topic shifts to something else, the opportunities will shift with it. So what I try to do is make sure I’m using my career to make sure I’m opening doors for other people — to make sure what I leave behind stays there.”

Roach arrives at the VFiles showroom to a swarm of admiring 20-something designers, all of them flushed for their mentor to give a final survey of the collections they’re set to present the next day at the VFiles runway show at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center. If I felt like a street urchin among the posh Hilfiger staff, here I feel like the world’s biggest square: Roach’s mentees are dressed like refugees from a cyberpunk dystopia, and their racks for the runway show spill over with looks that range from 24th-century ravewear to nu-metal desert nomad to sexy Gundam robot. There are chest plates made out of ’80s Nintendo controllers. People are wearing Crocs, somehow, in a cool way. The DJ A-Trak is, for whatever reason, wandering among the racks. I’m essentially just trying not to knock anything over. Roach, however, is deep in his element, beaming with inspiration at the abounding weirdness and draping himself in a knit scarf as big as a queen-size duvet.

Roach’s own style ethos hasn’t changed all that much since his Village Discount days, except for, well: “I can just afford more shit!” He laughs. “My style is expensive but also tacky in a way — an upscale tackiness. I don’t like perfect clothes: I’ll wear things that haven’t been hemmed, I’ll wear things wrinkled, throw it on. When things are too perfect, it takes away the personality.” And when he’s back in Chicago, he’s doing the same things he did in his Village Discount days, except from five-star hotels: Hit up Harold’s (preferably on 87th) and Portillo’s (his order is a beef and cheddar croissant with fries and a Sprite, because, he insists, “Portillo’s Sprite tastes like nobody else’s Sprite”).

The afternoon’s fading to evening, and we’ve got to head back to Midtown as soon as Roach finishes his VFiles walk-through and bangs out a couple of quick video interviews. He waxes about his love for Prince and Ariana Grande. (The Mean Girls– and Legally Blonde–inspired looks in the video for her song “Thank U, Next”? Styled by Roach, naturally.)

We make a pit stop at a jewelry store with a security guard in a suit stationed at the door. I am instructed to stay in the car, presumably due to the whole dressed-like-I-shot-a-man-in-Reno thing. Roach emerges after 20 minutes with what appears to be tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of diamond earrings, options for Zendaya to wear to a Lancôme fragrance launch this evening. “I need a vacation,” he sighs quietly. “All this stress is making my skin bad.” Fashion week hasn’t even officially begun.

Back at Tommy, where the elaborate breakfast buffet has been replaced by an elaborate dinner buffet, I wedge into a tiny office crammed with an all-black makeup team, Roach’s all-black assistants, and Zendaya, who pauses at the realization that the entire office building next to us can probably see her changing. She shrugs and changes anyway, slipping from hoodie and sweatpants into a polka-dot dress from her collection like she does this shit every day, which she probably does.

Law holds a couple of pairs of diamond hoops against her earlobes: one fairly modest, the other a blinged-out showstopper. “I dunno,” Zendaya wavers, brow furrowed. “I feel like the big hoops are a little … much.” Roach grabs her shoulders and gives them a gentle shake. “Don’t do that! Stop feeling that way!” he affectionately protests. “You are Zendaya! You can wear whatever the fuck you want!”

She smiles, relaxes. “All right. I’m wearing the big hoops.”