I love biography, both as a writer and a reader, and I certainly know much better the details of Michelle Obama’s life—and Hillary Clinton’s and Eleanor Roosevelt’s, just to name a few First Ladies—than I know the details and facts of the life of my own mother. Which is to say that there is no shortage of biographies even on the latest of the First Ladies.

Michelle Obama: A Life, published today, is written by Peter Slevin, a professor at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism and former writer at the Washington Post. The book is impressively reported and researched—Slevin acknowledges the research help of several of his students.

The outstanding chapter, in my opinion, is titled “Progress in Everything and Nothing.” It covers, in the most granular detail, Michelle’s three years at Harvard Law School, where she was accepted off the wait list. Slevin describes Michelle finding her way as black woman from a working class family in an institution almost as white and hidebound as her college, Princeton.

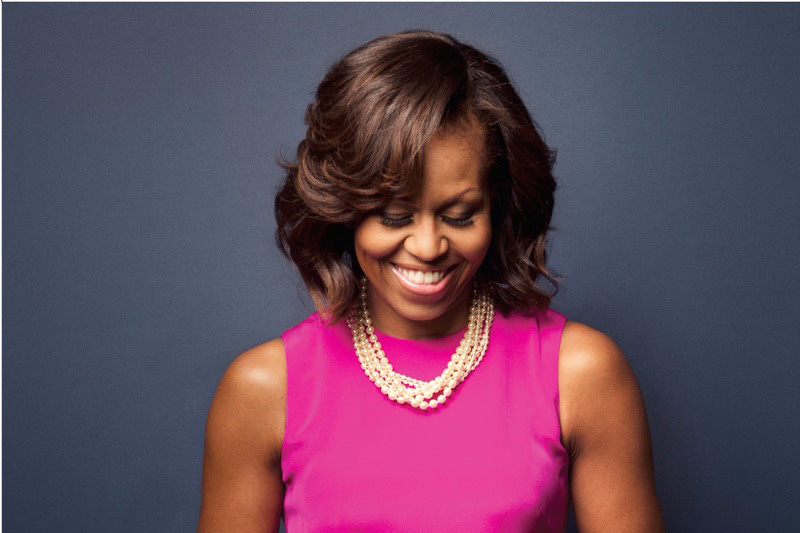

The new Michelle Obama biography, on sale today. Photo: Courtesy of Knopf

The new Michelle Obama biography, on sale today. Photo: Courtesy of KnopfSlevin is good in recounting the humble-yet-rich upbringing of Michelle and her older brother, Craig, in a one-bedroom, one-bath, un-air-conditioned apartment at 7436 South Euclid Avenue in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood—which was at the time transitioning from all white to all black. He describes their education at the neighborhood elementary school, Bryn Mawr, and the crucial role of Michelle’s mother, Marian Robinson, in her childrens' education. She tutored Craig with flash cards so he read at age four and had a leg up on his kindergarten classmates. The strong-willed, feisty Michelle refused to sit still for such drilling, but still managed to skip second grade and graduate as eighth-grade salutatorian. (Craig graduated as valedictorian.)

After graduating from Harvard, Michelle took a job as an associate at Sidley Austin, but soon found the lucrative work unfulfilling and boring. She decided to take a 50 percent pay cut and move into public service—specifically, Mayor Daley's administration. Two women who remain central to Michelle's life helped her find her way: Susan Sher and Valerie Jarrett. Sher, currently the point person in bringing the Obama library to the University of Chicago, was the woman who interviewed 27-year-old Michelle for a job in City Hall. She passed the prized prospect to Valerie Jarrett, then Mayor Daley’s deputy chief of staff. Jarrett offered Michelle a job on the spot. Before Michelle accepted the offer she asked Valerie to have dinner with her and her boyfriend, Barack. Slevin quotes Jarrett as saying that Barack “wanted to kick my tires”; to “tickle…out what I was all about.”

Jarrett and her parents—her father a physician, her mother an early childhood education pioneer—are presented with the kind of context that elucidates the White House’s most powerful yet mysterious figure; a woman often described as Michelle’s best friend or big sister. Jarrett's father, Jim Bowman, was the first African American resident at St. Luke’s Hospital here. In 1947, on his first day of work, he was asked to use the back door. He refused. When executives at Provident Hospital, where he had been the chairman of the pathology department, tried to lure him back after his service in the army, they offered him “less than half the salary white doctors were making.” Disgusted and discouraged, the Bowmans took their only child, Valerie, and moved to Iran, eventually returning to Chicago.

The University of Chicago also has a starring role in the biography— Michelle’s mother had worked as a secretary for the University in the 1970s and Michelle would take a job there in community relations just after the birth of her daughter Sasha. It’s depicted, in years past, as “a privileged and remote institution that tended to see the surrounding South Side black community as an unkempt and threatening backyard.” That was an opinion that Michelle certainly shared, once noting that the University “turned its back” on the community.

But back to Michelle—and, of course, Barack. Any book about Michelle ends up being just as much, or more, about Barack, and he takes over for pages at a time, often with some fresh details about well-known events. In one instance, Slevin recounts how the couple got engaged. Michelle insisted on getting married and Barack resisted, asking Michelle what a piece of paper meant, given that they were in love. She was having none of that: “If this isn’t leading to marriage, then, you know, don’t waste my time,” she told him over dinner at a fancy Chicago restaurant. When an engagement ring showed up on the dessert plate, Barack laughed and said, “That kind of shuts you up, doesn’t it?”

Slevin also included some interesting info about their wedding location. The South Shore Country Club, with its golf course and private beach, had a no Negro (and no Jew) policy. As whites moved out and joined clubs in their new neighborhoods, the club was put up for sale, eventually sold to the Chicago Park District and rebranded as the South Shore Cultural Center. In 1992, Barack and Michelle hosted their wedding reception at the Cultural Center (the ceremony, with Rev. Jeremiah Wright officiating, was held at Trinity United Church of Christ). Santita Jackson, daughter of the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Michelle’s best friend at Whitney Young High School, sang Stevie Wonder’s “You and I (We Can Conquer the World).”

Around this time, Barack took a job at the University of Chicago teaching constitutional law and began to work on his first book. His memoir, Dreams From My Father, which would later make the couple millionaires, was a commercial flop when it was published in 1995. It even failed to earn back its $30,000 advance. When Barack did a reading at Los Angeles’s “leading” African American bookstore, nine people show up. [Ed note: After this post was published, the editor of Dreams of My Father emailed saying that the advance was actually $40,000. Slevin's book cites it as $30,000.]

Five years after publishing his memoir, he decided to challenge Congressman Bobby Rush for his seat. When he lost the race by 30 points, Barack slid into a state of despair, feeling that he had been “personally repudiated” and that everyone who looked at him branded him with the word “loser.” He went to the 2000 DNC in Los Angeles that nominated Al Gore, but Hertz refused his American Express card because it had reached its credit limit. When he arrived at the convention center, he couldn’t even score a floor pass.

Realizing he was wasting his time there, he flew home—to an extremely angry Michelle, who presented him a list of childcare and household tasks and “a generally sour attitude.”

Fast forward to a set of lucky and unlikely circumstances that catapulted him into the U.S. Senate from his lowly state senate seat. In the kitchen of their Chicago home, Barack told Michelle’s brother about his plan to run for president. He admitted he wouldn’t be able to sell it to Michelle, so he asked Craig’s help in persuading her. Later, after his unlikely ascent to the White House, Michelle decided she needed her mom to move in with the family, and, this time, Michelle called on Craig to persuade their mother to make the move from her happy, humble routine in Chicago to the fishbowl/prison of the White House. Mrs. Robinson is the one family member who can escape the White House unnoticed, and she occasionally takes to strolling through downtown Washington. Once she was stopped by a passerby, who told her she looks just like Michelle’s mother. “Oh, yeah, people say that,” she responded, and kept walking.

Just a couple of omissions I noted: There's no mention of Betty Lu Saltzman, the Chicago Democrat activist and mega-donor who invited state senator Obama to give his anti-war speech in 2002, which gave him the distinction and chops to defeat Hillary Clinton. And there's almost no mention of Vice President Joe Biden, not even when Slevin writes about Barack’s belated support for gay marriage, widely seen as coming in the wake of Biden’s unexpected announcement of his support. Slevin depicts Michelle as uncomfortable with her husband’s reluctance on an issue that he fully supports, but cannot, for political reasons, admit to. Slevin quotes Michelle as telling her husband as he leaves for an interview with ABC’s Robin Roberts, during which he plans to declare that he has “evolved” and now supports same-sex marriage, “Enjoy this day. You are free.”

Slevin’s fast-paced, anecdote heavy book is as good a biography of Michelle as currently exists. But, for me, it lagged occasionally because I already knew the stories—I had read them in previous Michelle and Barack books by other journalists, by reporters for the New York Times and the Washington Post and the New Yorker and other magazines. And I myself had spent months researching Michelle for a cover story, “The Making of a First Lady, ” that was published in Chicago just as the Obamas were moving into the White House.

And one complaint: Slevin’s book brims with quotes both from people he interviewed and from people other writers interviewed. The distinction is not noted in the text, but requires the reader to flip to the back and check the chapter notes.

One last thing: On this day, Chicagoans will chose the man who will be mayor for the next four years. In his book, Slevin includes an interview with a Chicagoan who had a beer with community organizer Barack Obama, then 26, in 1988, shortly before he left for Harvard Law School. Obama told this man that, in ten years, he hoped to be mayor of Chicago.