|

|

They were dressed in black. Black boots, black uniforms, black gloves, black sunglasses, black guns. One wore a black ski cap. Against the blazing gold of the autumn leaves, which skittered and eddied in the cold November morning gusts, they looked as dark and ominous as a thunderstorm.

He was not dressed in black. Rather, he wore bone-colored chinos and a cheery chalk-striped Polo shirt under a light-gray Providence College pullover. His shoes were not black boots but hiking shoes—Hi-Tec mountain shoes, to be precise—the kind you expect to see on a soccer dad on a trail in Starved Rock State Park. They wore guns. He wore glasses.

The others looked like authority. He looked like the mild-mannered high-school math teacher you trusted with your problems.

They clomped up the back stairs of a two-story frame house off South California Avenue in Chicago Lawn. One of the men in black banged on the door. “Sheriff’s office!”

The landlord had called. He wanted them out. Time was, that would have been it. The men, deputies from the Cook County Sheriff’s Department, would have burst through the door, with a battering ram if necessary, and swept the tenants and their belongings onto the street. But that was before the other man had been put in charge.

The door opened. The apartment was bare. In the bedroom, a thin mattress lay on the cold floor. On a small round table, the lone piece of furniture in the kitchen, a few soggy circles of red and yellow cereal floated in a bowl of milk like the forgotten survivors of a shipwreck.

The couple, a thin woman in boxer shorts, with braided hair and large heart-shaped earrings, and a shirtless man whose sagging jeans rode so low on his hips that a good three inches of his own boxers were exposed, looked bewildered. The landlord wouldn’t take their rent, they claimed. He had, more than once, locked them out for several days. That was illegal, right? As they spoke, a little girl with pink and white plastic barrettes in her hair peeked around the corner and grinned.

“Well, hello there,” one of the deputies said. “How old are you?”

“Three.”

“Three? You’re so big!”

“You have beautiful hair!” added the man in the chinos.

“Thank you,” she said, smiling shyly.

The men in black listened patiently to the couple’s story, then looked to their boss, the man in the gray pullover and hiking shoes. “Should we call it off?” one asked. “It’s your call.”

The man, Tom Dart, the Cook County sheriff, knew that he could toss the family—even if their story were true. He knew some demanded it, believed to do otherwise was being a bleeding heart. He looked back at the little girl. She was already dressed in a red jacket, white gloves, and a white knit cap with a patch showing two hugging bears. She looked up at the man and smiled a wide toothy grin. His call.

* * *

Photograph by Ryan Robinson

NBC 5's Alex Perez interviews Dart last fall about some recent dogfight arrest.

An icy wind burns and scars . . . through the narrow space between these bars. Or so sang Warren Zevon on a CD playing in the office of the world’s most unlikely sheriff the day I arrived for a sit-down interview. I should have expected the serenade. Dart’s press spokesman, the former Chicago Sun-Times reporter Steve Patterson, told me that his boss almost always has music playing in his office—and indeed, while waiting for Dart, I noticed a pile of CDs scattered on a desk corner—mostly baby-boomer, white-guy stuff—Weezer, the Rolling Stones, Radiohead, the Ramones, the Clash, Bob Marley. Dart’s friend and former colleague in the Illinois General Assembly, Jack Franks, laughed when I mentioned the seeming eccentricity. “It’s true,” he said. “He’s a rock-’n’-roll sheriff.”

Aside from the tunes, the office contained a long desk, a small conference table, some framed pictures of Dart grinning with his four children, ages one to seven. A Gatorade bottle, the CD player, and stacks of reports outlining the daily drama that is the 10,000-inmate Cook County Jail, one of the country’s most famous lockups and the most demanding part of Dart’s job.

Indeed, on this morning, Dart, 46, breezed in, fresh from a meeting with the heads of the 11 jail divisions—from the ultramax Division 1, an ancient building that once housed Al Capone, to Division 11, a state-of-the-art 640,000-square-foot medium-security facility brought online in 1995.

The weekly “accountability” gathering, at which the division heads report on shanks found, fights broken up, fires started, homemade hooch confiscated, medical crises, uses of force, and attacks on staff, is something Dart implemented shortly after his election some two years ago, when he took over for his mentor and predecessor, Michael Sheahan, who stunned both Dart and the public by announcing he would not run again after 15 years as sheriff.

Despite the gravity of the reports—an inmate’s attempted suicide, a brawl involving nearly 40 gang members, a shank fashioned from a classroom ruler—Dart, noshing a bagel and sipping tea throughout, kept the tone of the meeting light. Most of the division chiefs wore dress shirts and ties, with badges glinting on their chests, and referred to Dart as “boss.” Dart, in his habitual pullover, leaned back in his chair, hands folded behind his head. He often punctuated his sentences with “bud” or “buddy,” as in “Thanks, bud,” or, “What you got, buddy?”

When one of the chiefs told Dart about a fight in the food line—“They were throwing spaghetti at each other,” the official said—Dart cracked, “I hope that’s not a comment on our food.” When another chief mentioned that a fight was over “an alternative-lifestyle issue,” Dart deadpanned, “You’ll handle that one personally—right, bud?”

* * *

Now, back in his office, Dart went right for the music, looking through the CDs, before leaving in Zevon and settling into a swivel chair at the conference table.

It would be a stretch to say that any Cook County sheriff operates in obscurity. The position is one of the highest-profile law-enforcement gigs in the state. And certainly Dart has had his share of media attention, good and bad—from his high-profile war on illegal dogfighting to a federal report last summer that blistered the jail he runs. Still, until his announcement in October that he was suspending evictions amid the foreclosure crisis, many would have been hard-pressed to pick him out of a lineup, as they say.

Sheahan, by comparison, was a veritable celebrity. From his physical appearance—the clean-shaven head, the power suits, the fierce expression—to his aggressive persona, to his name on buildings and buses, he was associated with the office in a public way. Dart? “I sometimes walk into a room and people ask, ‘Is the sheriff going to be here soon?’” he says, “and I have to say, ‘Um, it’s me.’”

All that changed, however, after his eviction moratorium. Suddenly, the rock-’n’-roll sheriff was a rock star, splashed across major newspapers from The New York Times to the Los Angeles Times. CNN’s anchor John Roberts interviewed him. Time magazine ran a Q-and-A under the headline “The Sheriff Who Wouldn’t Evict.” Even the tabloids weighed in. The National Examiner, known for headlines like “Oprah’s Gay Nightmare,” gave Dart above-the-fold treatment, portraying him as a combination of Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne under the morality-play headline “Big Hearted Sheriff Takes On Greedy Banks.”

But not everyone was so smitten. The “greedy banks”—in the form of the Illinois Bankers Association—initially accused Dart of “vigilantism” from “the highest level of an elected official.” The San Diego–based company Accredited Home Lenders filed a lawsuit, then withdrew it. (Both the IBA and Accredited declined to comment when contacted by Chicago.)

Some wondered about Dart’s motives. Just two months earlier, the Lake County sheriff, Mark Curran, had grabbed national headlines by spending a week in jail to get the inmates’ perspective. Was Dart seeking a little glory of his own? Looking for some good publicity to counteract the negative attention that rained down after the scathing federal report on the jail?

“I’ve met the man many times and he’s not a schemer,” says Russ Stewart, a longtime political columnist with the Northwest Side Nadig Newspapers who has tracked Dart’s rise. “He is generally forthright, but you can combine being forthright with being calculating and crafty. I would say overall that [the eviction moratorium] was a crafty move.”

Cook County sheriffs are known for many things—sharp elbows, political savvy, a tough-guy swagger. Sheahan was lauded for his ability to get things done, but was also called a “bully” by both John Stroger Jr., the late Cook County Board president, and the Cook County commissioner Mike Quigley. A Sheahan predecessor, Richard Elrod, was known as an old-school law-and-order pol who was about as touchy-feely as a park statue. But compassion? Empathy? No. Those are qualities for softies, not sheriffs. To be effective, you had to be mean. Or did you?

Dart downplays the fuss. For starters, he says, he had no idea his actions would attract so much attention. “As God is my witness, I could not have been any more stunned,” he says. “I felt I was simply calling attention to something that was morally and ethically wrong, something I couldn’t live with. I mean, this wasn’t a close call. To sit back blindly and use the excuse, ‘I was just following orders. I did what I was supposed to do’ is at a minimum a cop-out, at worst just reprehensible.”

His supporters scoff at the notion that Dart was seeking publicity. “He was working on making evictions humane long before the mortgage crisis hit,” says Dart’s General Assembly colleague Jack Franks. Dart’s wife, Patricia, just laughs. “He’s just always done the right thing,” she says.

Diane Limas, the head of the Northwest Side community group that called attention to the renter evictions by staging a protest at Daley Plaza, was skeptical until she met Dart. “He gave me the impression that he really did feel the injustice happening to these families and that he could actually feel their plight and their fear,” she says. “He seemed very humane. Very compassionate. I got the impression that he’s not your typical politician or sheriff who’s waiting for 20 OKs from somebody else to make a decision, especially when he feels the decision is right.”

In other words, his supporters insist, this is a sheriff with a heart. Really.

The truth is, Dart says, he has never been comfortable with the way his office has handled evictions. “I wasn’t in office more than a couple of weeks, maybe a month, and I went out with our crews,” he recalls. “Until you actually see it, you cannot fully appreciate what you’re talking about here. Think about it for a second. Think about a home you’ve lived in for ten years, maybe longer, and about the little knickknacks you have everywhere in your little kids’ rooms. Think about having someone—more often than not with a battering ram—knocking in your front door, moving you and your kids from the house, taking everything you own and putting it out by the street. Then think about the fact that in a lot of these neighborhoods, these belongings are routinely stolen.”

The numbers are staggering. As of mid-November, some 4,500 eviction requests had been made to Dart’s office. Overall, the number of foreclosures filed this year was expected to top 43,000—more than twice the number from two years ago.

Dart says his beef wasn’t with the evictions themselves. Landlords—or banks—have the right to seize their property when someone isn’t paying, no matter how sad the circumstances. At the very least, however, he felt his office should and could mitigate the trauma. Specifically, he wanted to connect the displaced tenants to social services that could help them cope. “I didn’t like how it was being done, so we started working on it,” he says. “We tried to get the landlords to go along with certain things, but they didn’t buy into it. We tried to introduce legislation in Springfield, but that didn’t go anywhere.”

|

|

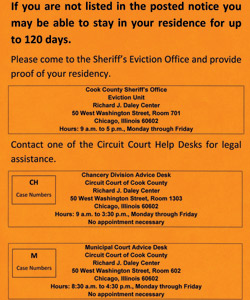

So, says Dart, his office began “winging it,” putting stickers on doors that spelled out exactly when the eviction would occur and where soon-to-be-displaced tenants could find help. “There was no rhyme or reason,” he says. “This is stuff we just created, just started throwing on the door. The problem is, things weren’t getting any better.”

Then came September, the Wall Street meltdown, the mortgage crisis, and what Dart discovered was a disturbing new phenomenon: Tenants who had faithfully paid their rent on time were winding up on eviction lists because, unbeknownst to them, their landlords had defaulted on the property.

The landlords continued to pocket the rent, says Dart. Meanwhile, “we were going out to house after house, where people had never been informed of anything. The only thing they knew was us showing up at the door in our black suits saying, Get out. Evicting these people was clearly wrong. They’d done everything right. It was outrageous.”

The issue was crystallized for Dart when Limas’s group showed up at the Daley Center after one such eviction. Often in those situations, bureaucrats will hunker down, defend their position, and promise to look into things. “My position was, We have no argument with you,” says Dart. “You people are right. They were shocked.”

“We were just glad that the sheriff had the courage to take that bold of a stance,” Limas says, “because it’s been our experience with elected officials that there aren’t many who will.”

The problem, Dart says, was what to do. He could try to get a law passed, but that could take months or years. Meanwhile, people were still being unjustly put out. So he simply stopped all evictions connected to mortgage foreclosures. “Yes, it was radical,” he says. “But it needed to be done. Anything short of that, and things were not going to change. I knew from my tortured past exactly what would have happened. There would have been meetings and committees—meanwhile, we would be tossing more and more people on the street who had no idea what was going on.”

In the media, Dart was cast as a hero—a maverick, to borrow the word. Sheriffs from across the country began calling for advice. Some, such as Sheriff Robert Pickell, of Genesee County, Michigan, imposed moratoriums of their own. McHenry County sheriff Keith Nygren says he designated a deputy to alert renters that the property would soon be seized. “I support [Dart],” Nygren says. “I think he’s to be commended.”

The banks, assuming Dart was suspending all evictions, even those not connected to foreclosures, were initially incensed, but toned down their rhetoric after receiving clarification from him. “Tom Dart is a great sheriff,” says Richard Gottlieb, a member of the executive board of the Illinois Mortgage Bankers Association. “This is not about Tom Dart. We believe what he did [regarding the rent-paying tenants] was absolutely fair. . . . It was to the extent he was saying he was going to stop all evictions that we felt he was going too far.”

Within days of announcing the moratorium, Dart met with Judge Dorothy Kirie Kinnaird and worked with members of the Cook County Circuit Court’s chancery division to overhaul the eviction process. As a result, landlords now had to prove that they had informed tenants of an already existing 120-day grace period.

A week and a half later, Dart declared the moratorium officially over and said that foreclosure evictions would resume. But when he returned to the streets, he realized that nothing had really changed. The 120-day notice had yet to be served on the renters in the foreclosed properties. “We didn’t put out a single person,” he says. Indeed, as this story went to press, Dart had carried out only three of 110 eviction requests made since the moratorium, a number he expects to increase dramatically in the months ahead.

For Limas and rent-paying tenants, Dart’s stand was a triumph. For the public at large, it was cause for a question: Who is this guy?

* * *

Photograph by Ryan Robinson

Dart and chief deputy sheriff Kevin Connelly leave a house in Englewood after serving an eviction notice.

In the movies, the sheriff’s gut hangs over his belt, his jaw bulges with tobacco, his leather holster creaks, and he says BINGO! after he spits. It’s a cliché long discarded—these days, the big-city sheriff often looks and acts more like a ward heeler than the clichéd good ol’ boy. But vestiges of the old lawman stereotype remain: the tradition of the sheriff as a former cop with a reputation rooted in toughness.

Enter Dart. Though he was a prosecutor for a time and cochaired an Illinois prison oversight committee, he was never a police officer. Never carried a gun. Never made an arrest.

He’s never been accused of being a wimp—as an assistant state’s attorney, he was relentless in rooting out and prosecuting corruption in the Ford Heights police department. Beyond that, however, his background seems more community do-gooder than tough-guy top cop: tutoring kids at Cabrini-Green, starting a flag-football league for children he felt were too young to be in pads, state representative from a ward that was mostly African American. Even when he did ascend to the Cook County sheriff’s post, he shunned many of the office’s trappings: He has no driver, no security detail. He doesn’t plaster his name on every order, every placard. When summoned in November to testify before Congress about his eviction moratorium, he packed his three staffers in his Chevy Tahoe and drove to Washington, D.C., to save the county the airfare. He rides his bike to school each morning with his son.

“Dart is a very intellectual guy,” says Russ Stewart. “He’s not the big, bruising type of sheriff you customarily envision in the office.”

He’s aware that he’s a different breed. “That’s been reinforced to me several times,” he says. “When I meet with other sheriffs, say from Downstate, it’s abundantly clear that I’m not the norm. They laugh about it. I laugh about it.”

* * *

Raised in Beverly, Dart and his wife, Patricia, along with their four children, live two miles from Dart’s parents. Early on, he felt drawn to politics—to the dismay of his father, who, as a lawyer in the corporation counsel’s office of Richard J. Daley, advised against that kind of career.

“He thought I’d have a much more satisfying life not having to deal with the despicable people you sometimes found in politics,” Dart says. “He thought it would be easier just to practice law and make some money.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in history from Providence College, Dart returned to Chicago to attend law school at Loyola University. In 1987, the freshly minted lawyer landed a job as an assistant Cook County state’s attorney. Over the next five years, he prosecuted hundreds of felons, and he headed the Ford Heights corruption investigation, which resulted in the conviction of police chief Jack Davis and five other officers on charges of extorting bribes from drug dealers and abetting them in their distribution of heroin and crack.

Dart might have continued in that role, but in the early nineties, Jeremiah Joyce, a staunch ally of Mayor Daley, resigned from the state senate. Dart, who lived in Joyce’s 19th Ward (as did Sheahan), was appointed to fill the vacant seat. A year later, he ran for a seat in the Illinois House from the 28th District, a diverse swath of the South Side that included parts of Roseland, Pullman, Morgan Park, Mount Greenwood, Calumet Park, and portions of Blue Island. Dart was a long shot. His opponent, Nelson Rice, was an African American incumbent in a district that was more than 60 percent black.

But Rice was ailing and unable to campaign actively. Dart, by contrast, was tireless. “I just went everywhere,” he says. “I knocked on door after door. I also had some credibility within the African American community from things like tutoring at Cabrini-Green.”

Still, he recalls, “my father was so sure I would lose that he called me on election night to console me. I said, ‘Well, Dad, there are still some votes out there. Let’s see what happens.’ I ended up winning by a few hundred votes.”

In Springfield, Dart developed a reputation as a reform-minded legislator and a royal pain in the ass—mostly for the extraordinary number of bills he proposed. Unlike most members, he did not have a lucrative outside job, which left time to focus all his considerable energy and attention on researching and proposing new legislation. “If you pulled up the number of bills I introduced, you’d probably find yourself laughing,” Dart says. “I’d find myself reading something, a book or an interesting magazine, and I’d rip it out, research it; then I’d introduce a bill on it.”

Thus, he sponsored bills on everything from hog farming to the designation of Drummer silty clay loam as the official state soil. Much of his legislation went nowhere (the soil bill did pass in 2001), but he did have successes—namely in his efforts to bring sweeping changes to the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services.

“He was different from other reps,” says Franks. “He read everything. He worked so hard. He took his job very seriously. He was not what you’d consider the typical pol.”

He was a good interview—and telegenic. He often wound up on one of the cable television programs produced by the office of the Illinois House of Representatives speaker, Michael Madigan. One of Madigan’s staffers saw more than just an articulate policy wonk. Patricia McAdams married Dart in 2000. “There were no airs about him,” she says. “And he knew everything. People could never say a bad thing about him.”

The longer he spent in the General Assembly, however, the more he felt his returns diminishing. His bills were sometimes ignored. “After a while, I was spending more time fighting my own party than accomplishing what I wanted,” he says. “I wasn’t being productive anymore.”

At least one big positive came out of those tough times. Among the legislators with whom he commiserated was a skinny, thoughtful, well-spoken state senator named Barack Obama. “That’s how we got to know each other,” says Dart, who considers Obama a friend. “We would meet and talk about” their shared tribulations. The two partnered on child-welfare reform and criminal justice, and later Dart would help run Obama’s unsuccessful campaign against Congressman Bobby Rush.

Dart left the legislature in 2003, and after an unsuccessful campaign for Illinois state treasurer (he lost to the Republican incumbent, Judy Baar Topinka), he was appointed to serve as the chief of staff to Cook County sheriff Michael Sheahan. In 2005, he was deciding his next move—“As much as I enjoyed what I was doing, it wasn’t something I saw myself spending the rest of my life doing,” he says—when Sheahan abruptly decided not to run again. The timing, just as the Democratic Party was choosing its slate of candidates, was auspicious.

Sheahan immediately endorsed Dart, a move that infuriated Rush, who believed Sheahan was trying to shut out other possible candidates, including black and Latino hopefuls. (Rush did not respond to interview requests from Chicago.) In March 2006, Dart won the Democratic primary election by a wide margin, beating two former Cook County Jail officials, Sylvester Baker and Richard Remus. He won the general election in November 2006.

During his 16-year tenure, Sheahan had been praised for some of his early reforms, such as creating a boot camp for first-time offenders. But his tenure was also dogged by controversy, including chronic overcrowding in the jail and numerous allegations of abuse of inmates by guards.

Dart quickly instituted a number of reforms. He raised the hiring standards for Cook County guards, installed new technology in the Cook County Jail, and created a number of programs for women inmates, including a “bright space,” where soon-to-be-released women could spend time with their children in a comfortable, homelike environment. “The challenge for Tom is that he inherited an office where it’s hard to change the culture, and I would argue it’s a culture that needs changing,” says Quigley. “But I give him high marks for trying. I think he’s a nice guy; I think he’s a tough elected official. I think he’s in a tough spot.”

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo by Nancy Stone

No spot was tougher, no seat hotter, than the day last July when the Department of Justice issued a scathing report about conditions at the jail. The report said, among other things, that the jail was unsanitary and had failed to provide adequate medical care and suicide prevention.

Dart believes the report exaggerated isolated incidents and failed to note his accomplishments. “Some of the criticism was accurate, and then there was a majority of it that was completely out of context,” he says. Charles A. Fasano, the director of the Prison and Jails Program at the John Howard Association of Illinois, agrees that Dart got somewhat of a raw deal. “By and large, he has really taken a fresh look at stuff,” says Fasano. “The jail, for example, is less crowded now than it has been at any time in the last 20 years, and Cook County’s suicide rate is among the lowest in the country.”

While it’s true that the jail’s medical care needs vast improvement, Fasano says, those services are not under Dart’s purview. “When the [federal] report came out, and they had all that scathing stuff about the medical end, it sounds like it’s the sheriff’s problem. Well, it isn’t.”

The eviction issue has brought Dart far better publicity. “Today’s American Hero,” declared one blog. “The sheriff who wouldn’t evict” was how an NBC 5 Chicago reporter referred to him. These days, Dart can even joke about the initial threats of lawsuits and contempt charges from the mortgage associations.

“There’s a new sheriff in town, all right,” Dart told the City Club of Chicago in October. “People tend to think of the sheriff’s office [as] Andy Taylor, Barney . . . the traditional cowboy hat, a six-shooter. . . . You just didn’t realize you got yourself one who apparently isn’t big into following the law. It’s a fascinating concept.” The crowd laughed. “I don’t think I’m going to arrest myself,” though, he added. More laughter. “If I do, . . . I’ll put myself on home confinement.” Applause. “At the Four Seasons.”

* * *

The three-year-old girl with pink and white plastic barrettes gazes up at the man in the chinos and gray pullover as if waiting for an answer. The couple in this instance aren’t one of Dart’s “no-brainer” cases—renters who have paid in good faith only to be told they have to get out. The case is more complicated. The landlord, for example, had insisted that he had not locked the couple out, but screw holes in the door suggested that he had mounted and removed a deadbolt. And something in Dart’s gut tells him the woman with the plastic heart-shaped earrings is telling the truth when she says she filed a motion with a judge to stay the eviction.

And so Dart, looking and sounding more like a social worker than the county lawman, grants a reprieve. “We need to know all the facts,” he tells one of his deputies out of earshot of the couple. “Let’s give it another day.”

“We’re going to give you a couple of days here,” he says, turning to the woman. “So if you have some paperwork, please get it. It may be the case that the landlord is still within his rights to have you put out, but at least you’ll have a chance.”

He casts a glance at the girl. “But please do this, OK? You two will be all right; you can probably find a place. But for her sake. We don’t want to put her out in the cold.”

The couple nod. The little girl, in her red coat and white cap with bears, giggles. And the unlikely sheriff, his black-uniformed deputies in tow, heads down the back stairs, out to his Tahoe, and to the next home, where he also grants a reprieve. There will be more evictions one day, just not this day. Instead, Dart drives back to his office at 31st and California, the one that stands in the shadow of his jail. He settles behind his desk and he fires up some tunes, The Clash, or the Rolling Stones, or Warren Zevon—and gets down to business.