On a Saturday afternoon last October in the West Loop, an audience of about 35 people sat in rows of folding chairs in the spacious second-floor salesroom of the Wright auction house. At one point, the auctioneer offered a stool, circa 1954, made of walnut and chrome-plated steel, a design by the Japanese artist Isamu Noguchi. Its catalog estimate was $5,000 to $7,000. The bidding soon came down to a competition between the two principals of Wright, a boutique business founded in 2000 to specialize in modern furniture and objects.

At the front of the room behind a lectern, Richard Wright, the auctioneer, represented clients who had made earlier bids. Richard’s wife, the interior designer Julie Thoma Wright, held her customary spot at the phone bank that extends along the side of the room. There she and other staff members called clients who had arranged to bid on the phone; another employee handled bids made through the Internet.

The competition turned edgy. Every time Richard announced an increase in the bid, Julie’s right arm shot into the air as she topped him on behalf of her client. She looked determined and willful, and intent on winning. Richard seemed amused by this display and yet proud of Julie. The brief exchange was public, but those few minutes seemed intimate, a fleeting scene from an exceptional marriage.

As the volleys continued, Richard finally laughed and said, “It’s always nice to dance with my wife.” His bidder won at $7,200, but Julie had done her best. Later, she offered this interpretation of her marriage: “I think we have that rare quality of making each other better.”

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| This 1954 ball wall clock by George Nelson and Associates was sold at Wright in December 2005. |

Individually, the Wrights are accomplished; together, they are a force. “Julie has had a tremendous vision of what Wright could and should become,” says the architect Geoffrey Goldberg. “She and Richard have understood what modern design could mean on an international scale and in the marketplace, and they also have had the organizational skills and the savvy to put their business in place.”

In only six years, the Wrights’ ideas, their drive, and their distinctive presence have propelled their auction house to a position of unparalleled prominence. A high-school homecoming queen, Julie, 48, has wide-open eyes, a pale, luminous face, and short blondish-gray hair. Richard, 43, with aquiline features and curly dark hair lightly streaked with gray, is leading-man material. Both are slim, and in four-inch heels, Julie is as tall as he is. Her voice is light and lyrical; his is deep and mellifluous. He prefers Prada and Hermès and seems pleased that, having made that decision, he does not have to think too much about getting dressed; she mixes couture designs with vintage jewelry in such a sophisticated way that she looks unlike anyone else.

In the past year and a half, the Wrights have taken their professional and private lives to another level. They completed the move of their auction house to larger quarters in the West Loop in January 2006, a reinvention that consolidated and streamlined their operations. In March, House & Garden featured the Wrights, noting, “If modernist design today is a high-end auction category, much credit goes to them.” The following month, in T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Julie and Richard were the first figures in a four-page feature entitled “The Originals: These Mavericks of Design Have Always Done It Their Way.”

Photograph: Selena Salfen |

| A year later, at the Important 20th Century Design sale, Richard brought down the gavel on the architect Pierre Koenig’s modernist house built in California in 1958. |

In May, Crain’s Chicago Business recounted Wright’s record-breaking $630,000 December 2005 sale of a marble, birch, and aluminum table designed in 1948 by Noguchi. That table would later be featured in an Art & Antiques cover story citing the 100 most outstanding objects of art traded in the past year.

After their three auctions at the end of May, the Wrights moved into a recently restored late-19th-century house in Kenwood designed by the architects Dwight H. Perkins and H. H. Waterman, and Julie began transforming the interiors into a blend of the historic and the contemporary. In the fall, Richard was chosen to appear in a video and print advertising campaign for the new BlackBerry Pearl. Julie was asked to furnish two residences for a fellowship program on the estate of the late architect Philip Johnson in New Canaan, Connecticut.

In 2005, the Wrights held seven sales; in 2006, they doubled that number and also auctioned off an architecturally significant midcentury house in California-their first such endeavor-along with its furnishings and the owner’s 1958 Porsche 356 Speedster. Except for the sale of the house (and then at the owner’s request), the Wrights have never had a public-relations person. They seem to generate their own heat.

Even with a place at the center of the design universe, the Wrights remain down to earth, haute without the hauteur. Take Julie’s sense of style. “She loves fashion, but she’s not elitist about it at all or judgmental,” says the interior designer Karen Lilly Mozer. Among Julie’s favorites: Chanel, Lanvin, Jean Paul Gaultier, Alexander McQueen, Dries Van Noten. “I’ve always had fashion-forward ideas about how I wanted to dress,” Julie says, “and it was mostly out of my own creative interest.”

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| A Zig-Zag chair by Gerrit Rietveld went for a high price. |

She retains her style and her composure despite a serious illness. In the summer of 2004, Julie was diagnosed with colon cancer and has been undergoing treatment since then. “It has altered my life and my time to enjoy it,” she says. “But I still enjoy life so much-and our marriage and our kids and our business.”

Julie has a son from an early first marriage, Nicholas, now 22 and a senior at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Married in 1995, Julie and Richard have two sons, Adler, three (named for the architect Dankmar), and Emerson, five (named for the poet). Adler and Emerson attend the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools.

Except for auction days, Richard says, he and Julie almost never work on weekends. “We spend every morning with our children. I get to work at about 9:30, and when things are good, I leave at 5:30 or 6. I like to see my children and put them to bed. It’s depressing to me to come home when the children are asleep.”

Julie goes to the office for meetings but sometimes works on her laptop at home and usually picks up the children from school. She handles her illness with grace, and often, for others, almost succeeds in making the reality of it go away. “Julie is just so tough that she gives the appearance of ignoring it,” says Michael Jefferson, a 20th-century specialist at Wright, “almost as if it’s not even there, to me, to us, to the outside world.”

Jefferson says that Julie’s illness has made the Wrights more driven than ever. “They’ve wanted to get us to a great place,” he says, “get us into this building, take advantage of the kind of power and charisma that they have together and build this company in a focused and aggressive way so that we’re in a strong and stable place.”

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| A planter by LaGardo Tackett went for a high price. |

Julie and Richard both grew up in small towns-she in Le Mars, Iowa, the self-proclaimed ice-cream capital of the world; he in Topsham and Brunswick, Maine, and briefly in Asheville, North Carolina.

Her family lived in a town near an isolated farming community. Her father was a builder, and her stay-at-home mother was an excellent seamstress who made many of the clothes for her eight children. “We were fashion from head to toe,” Julie says. Her classmates elected her a homecoming queen because she was social, willing to lead the pack, get things started.

“And you were pretty,” Richard adds. “That didn’t hurt.”

She knew then that she wanted to be an interior designer, and in 1981, after graduating from Iowa State University in Ames, Julie accepted the invitation of a family friend to come to Chicago to work on the interiors of his house. Then one day in the Merchandise Mart, she met the interior designer Arlene Semel. “I was in a show room, and I saw this attractive woman walking out,” Semel recalls. “She came to the office; she had a beautiful portfolio, and I hired her.”

Three years later, in 1984, Julie started her own firm, Thoma, Inc., and in 1989 she won an honor award from the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects for a laundry room that she had designed for a high-rise apartment building in Hyde Park. “Fabulous, fresh . . . loving attention to a usually unattended-to space, on no money . . . a star is born,” the jury commented.

“I think that single event gave me a real place in Chicago’s design community,” Julie says, “and I went from working solo into some large firms.” At ISD (Interior Space Design), which was later bought by A. Epstein and Sons International, most of her projects were corporate headquarters. In the early nineties, while making her usual rounds-the kind of legwork that designers do to stay informed about sources-she discovered Richard’s shop at 2779 North Lincoln Avenue, where he specialized in 20th-century furniture and objects. She bought a Gilbert Rohde desk there for a client, a Noguchi lamp for a friend.

“His shop was carefully curated,” Julie recalls. “It was a combination of his eye and his knowledge. Other shops had a vintage feel; his had a gallery feel.”

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| Wright sold this table by Isamu Noguchi for $630,000 in 2005. |

Richard was raised by his mother, formerly a physical therapist. “I never actually met my father,” he says. “They got divorced quite quickly. My mom remarried later, and I have a sister who is nine years younger. That, too, ended in divorce.” His sister, Kathy Frey, is now a Chicago jewelry designer.

In Maine, Richard’s maternal grandmother lived nearby. “She was a bit of a grande dame,” Richard says. She traveled extensively and was well read, collected antique dolls and had an apartment filled with Oriental rugs and African artifacts. “Looking back,” Richard says, “I can see that she was the first one to give me the idea of a broader world beyond Maine and an intangible sense of the beauty of objects.”

His mother detected an early alertness to detail in her son. “When he was about two, he liked to pick out his own clothes when we went shopping,” she recalls. “He needed the right color-it depended on his mood.” In high school he had to have Izod shirts. “Then maybe around his senior year,” his mother says, “it was overalls, but he only used one strap. The other one was just dangling.”

Richard attended the University of Massachusetts in Boston for two years-he wanted to be a writer-but it wasn’t long before he and Martha Torno, his girlfriend at the time, took off in a van. “He regrets not finishing college,” his mother says. “But he didn’t need it; he’s a genius in my book.”

His first exposure to midcentury items came in 1986, when a friend told him that you could buy vintage trench coats in the Midwest for a dollar and sell them in Boston for $20. “I became intrigued by that business model but quickly discovered that I didn’t like going through clothes,” Richard says. “I was immediately drawn to objects from the fifties and started taking them to flea markets in Boston.” He was ahead of his time there; someone told him that he needed to go to New York.

For the next two years, he and Torno became pickers, traveling to New Orleans, Texas, New Mexico, and on to Arizona and Los Angeles, buying objects-ashtrays, lamps, kitschy items-and selling them at the Rose Bowl Flea Market, then driving back across the country to the 26th Street Flea Market in New York.

In 1988, he and Torno moved to Chicago-the Midwest was the best place to buy-and set up a booth in an antiques mall on North Clark Street near Belmont Avenue. A year later, they opened a 700-square-foot shop, Torno Wright, on Lincoln Avenue. When they split up in 1990, he kept the shop and renamed it Richard Wright. (Torno and her husband, Tom Clark, now own Chicago’s 20th-century furniture and art gallery Modern Times.)

Jay Dandy, a freelance copywriter, recalls stopping by Richard’s shop in the early nineties and seeing an Eames surfboard coffee table and a lighter in the shape of the research tower for Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wisconsin. “Everything looked elegant and wonderful,” he says.

“I was quite proud of the store, but it was tiny,” Richard explains. “And it was hard to sell higher-end things in Chicago. Julie aside. I decided to move to New York, where the market was much more active.” In 1993, he put a going-out-of-business sign in his window, and not long after that, Julie called. The Wrights’ recollections of that fateful exchange differ.

Julie: “I asked you why you were closing, and you said because you were moving to New York. And I said, ‘Well, I have to know how to find you there. Let’s have lunch.'”

Richard: “My memory is that she said, ‘Well, you haven’t really gotten to know me yet. Let’s have lunch.'”

But they agree on the outcome. “We had a really fast romance after that lunch,” Julie says. When she explained to her son that she and Richard would be dating, Nicholas responded with a simply stated double-entendre: “I think you have something for him.”

|

Photograph: Selena Salfen |

| Julie and other staff members on the phone and the Internet at that sale. |

Richard closed his store and moved in with Julie and Nicholas in Hyde Park. He took the summer off and enrolled in college English classes, intending to complete his bachelor’s degree. That plan was interrupted by an offer to join the recently founded modernism department at Treadway/Toomey Galleries, cooperative auction houses based in Oak Park. When the head of the department left, Richard took charge; he worked on commission and supplemented his income by collecting items on his own and selling them at modernism shows.

In 1995, he and Julie eloped to Italy and were married in Florence in a civil ceremony at the Palazzo Vecchio, the Medici palace. “It was beautiful,” says Richard. “It was a magical day.”

Within a few years, the Wrights reached another turning point. Richard knew that an exhibition of the work of the innovative midcentury American designers Charles and Ray Eames was originating in Europe and would open at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1999. More than a year in advance, he began collecting material for an Eames auction at Treadway/Toomey Galleries that would coincide with the show. “I got deeply involved in the world of Eames,” Richard says. “It was a great experience.” In an essay for the auction catalog, he wrote: “Eames design is far more than the sum of its parts-it is beyond a chair, a photo or a house. Charles and Ray Eames designed a unique and compelling world. They designed a life.”

Sales for the March 1999 auction totaled $600,000, and the experience gave the Wrights the confidence to start their own auction house. “We really wanted to have a company that was about those creative moments,” Richard says, “that was built around that kind of modernist aesthetic.” Asked about Richard’s tenure, John Toomey of Treadway/Toomey Galleries said that he had no interest in revisiting the past but he gave Richard a lot of credit for what he had accomplished at Wright.

“He had the gumption and the foresight to move ahead and do what he did,” says Gene Douglas, the co-owner of DouglasRosin Decorative Arts & Antiques. “He had a dream, and he followed it.”

In April 2000, Julie and Richard rented a 5,000-square-foot rehabbed loft at 1140 West Fulton Street. “That one space was the office, the gallery, the auction salesroom, and the warehouse,” Richard says. Julie moved her interior design practice, Thoma Wright, Ltd., there, as well, and in the beginning, her business sustained the Wrights’ income.

Richard asked his friends in the industry and the collectors he knew to consign items to his first auction, held on June 4, 2000. Featuring designs by Alvar Aalto, George Nelson, Edward Wormley, Charles and Ray Eames, and T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, the sale brought in $400,000.

Jay Whipple, an investment adviser from the North Shore, was there to buy the first lot-a 1950s ball clock by George Nelson. He and his wife, Anne, had been clients and fans of Richard’s when he was at Treadway/Toomey, and Jay wanted to show his support. About five years later, he gave the clock back to Richard as a keepsake.

|

Photograph: Selena Salfen |

“The whole reason Wright exists is the network formed by our partnership,” explains Julie, who created the management and marketing structures for the new operation. “At this point we have a staff of 17, and I’m just working on the creative and marketing end of things. Richard is the rock star. He’s the rainmaker.”

Although Wright is most often identified with postwar design, it has a much broader range-from turn-of-the-century works by architects such as Josef Hoffmann and Louis Sullivan through art deco and on to pop and contemporary design by standouts such as Fernando and Humberto Campana, Ron Arad, Marc Newson, and Zaha Hadid.

From the start, Richard tried to give the selections a curatorial point of view, as he had at his shop. And Wright’s exquisitely designed catalogs quickly distinguished it from other houses. “What you’re selling is design,” Richard says, “so you should have a well-designed catalog for design-conscious people.”

“Julie and Richard helped redefine what auction catalogs can be,” says the interior designer Karen Lilly Mozer. “They presented them like museum exhibition catalogs. It was really smart; it was calculated, and it worked.”

Within a year, there was no need to solicit consignments; they came to Wright. The clients included dealers, collectors, and institutions such as museums and foundations. Soon The New York Times was tracking Wright’s sales and reporting on the high prices the auction house brought in for items such as a Gerrit Rietveld chair and a Vladimir Kagan sofa. In 2005, when Wright held its first Branded Luxury sale of steamer trunks, crocodile handbags, and other chichi accessories by designers such as Louis Vuitton, Hermès, and Cartier, a reporter for the Times flew in to cover the event. Richard was quickly becoming a modernist authority and a marketplace seer.

“What I’m really trying to focus on is what interests us,” Richard says. “I think if you’re trying to chase a trend or create a trend consciously, you can miss the mark. So I don’t claim to be able to predict at all.”

He cannot deny, however, that he and Julie are clever about new concepts. “Of all the auction houses,” says a Chicago financial adviser who asked not to be named, “Wright may be the most innovative, the most willing to create a new category of auction.” In the past two years, the house has added, among other sales, Books of Art + Design, Post War + Contemporary Art, and Important Italian Design. Wright’s small size and its independence-there are no partners-give it a flexibility that some of the larger houses do not have. And in sales it is third behind the modernism departments of Christie’s and Sotheby’s. In 2006, Wright’s gross revenue was $25 million.

|

Photograph: Selena Salfen |

| The unidentified buyer of the Koenig house in the audience (second from left). |

By 2005, the Wrights had doubled their space on Fulton and were also renting a 10,000-square-foot warehouse. Julie decided that it was time to upgrade. After their first visit to 1440 West Hubbard Street, she mapped out their business model on the floor plan of the space, and it was a perfect fit.

“There have been several key times in my career where Julie has come through with a high vision and helped take us to another place that I wouldn’t have gotten to on my own,” Richard says. “This was a much bigger building than I was looking for, and the overhead is triple what we were paying. It was scary to me.”

The Wrights signed the lease on the 60,000-square-foot facility in June 2005. Part of an even larger two-story red-brick building, the space had formerly housed a printing company. With few changes, the Wrights were open for business. “After being here a short time,” Richard says, “I realized that it was absolutely the right decision to move.”

On the first floor, the room that had held the printing presses was converted into the main exhibition hall; that level also now comprises the reception area, the research library, and offices. In the back, two indoor bays can accommodate 52-foot-long trucks; objects are unpacked and inventoried in a receiving area and then sent to one of two photography studios. The salesroom, Richard’s office, the graphics room, and additional preview and storage space are situated on the second floor. The Wrights hope to buy their space this year and begin implementing their master plan for a redesign of the interior.

Gene Douglas points out that Wright has a strong team backing up its operation. “Everyone who works there is onboard,” Douglas says.

To name a few: Julie’s youngest sister, Kelli Thoma, 37, worked with her at Thoma Wright, Ltd., when she had downtime from her jobs as a stage manager; she is now the director of operations at Wright. Brian Franczyk, 51, the director of photography, was also there at the start, giving the catalog images a painterly still-life quality. Michael Jefferson, 33, has a background in fine arts and was on the staff at the Prairie Avenue Bookshop before he became fascinated by modern design; as Gene Douglas puts it, he is Richard’s right-hand man. Jefferson’s brother Peter, 28, came to Wright to move furniture and now is in charge of the book and Branded Luxury sales. Lyz Nagan, 28, had previously managed an art gallery and worked at the Hyde Park Art Center before she began writing the catalog copy. She initially volunteered to be an unpaid intern for two months at Wright and was hired full-time within two weeks. A Julie decision.

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| Julie on the cover of Wright’s catalog for its Modern Design auction in June 2002. Her Miu Miu skirt was not for sale, but the 1933 armchair by Gerald Summers and the 1988 screenprint by Richard Estes were. |

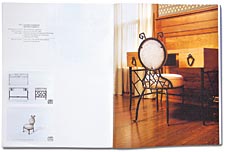

One afternoon in late October, Julie was in the graphics room at Wright working on the catalog for the December 3rd auction, Important 20th Century Design. The sale offered a strong selection of furniture and objects designed by architects-among them, Gerrit Rietveld, Paul Rudolph, and Robert Mallet-Stevens-and Julie had decided to open the catalog with that. “We’re trying to show them as an architect would like them to be seen,” she explains, “not in a decorative way.”

Several rooms of furniture and accessories designed in 1992 by the neo-baroque architects Elizabeth Garouste and Mattia Bonetti for a house in Germany were to be offered late in the auction. Julie was disappointed with the initial photographs of those pieces, which were taken at Wright against a white sweep. Based on the style of the work-much of it made of oak and bronzed steel-and some research, she decided that it should be photographed again, this time at her house. “I didn’t think we should sell these pieces without showing them in an environment,” she says, “and we have a lot of rich woodwork and wallpapers.”

Julie had other plans for her house that weekend. Halloween has become the big blowout holiday in the Wright family, and that Sunday she and Richard were holding their third annual carnival-like extravaganza for their kids. Seven of Julie’s family members were flying in, and one of her sisters would be leading a line dance of superheroes down the driveway. Richard was going to be a pirate; Julie decided to be a princess for most of the party and then reappear at the end as Superwoman. None of this, of course, would interfere with having the catalog completed on time for the December 3rd auction.

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| The catalog that Wright produced for the auction of the Pierre Koenig house featured original and new photos; those below, from 2006, are by Julius Shulman, who was first there in 1959. |

An auction is its own kind of theatre, and the event in early December was high drama. At 1 p.m., an hour into the Important 20th Century Design sale, Richard auctioned off a 1,320-square-foot glass-and-steel house built by the architect Pierre Koenig in the late fifties in Los Angeles, California.

The residence-Case Study House #21-was one of 36 buildings that John Entenza, the editor of Arts & Architecture, had commissioned beginning in the late 1940s to promote the principles of modernism. He published photographs of the completed projects in his magazine.

Mark Haddawy, the owner of the vintage stores Resurrection in Los Angeles and New York, had bought the house in 2002, but when his girlfriend, the actress Nora Zehetner, moved in a year and a half ago the space seemed too small. At the Los Angeles Modernism Show last spring, Haddawy ran into Michael Jefferson and told him of his plans to sell the house at auction rather than through a broker. Haddawy had been a client of both Wright and Sotheby’s over the years, but in this case, he finally decided to go with Wright.

“There’s a big difference between Richard and Sotheby’s,” Haddawy says. “Richard is the auction house, so the amount of red tape that needs to be dealt with is a minimum. If Richard and Julie decide that they want to do something, then it’s going to be done.”

Lyz Nagan managed the project, and Wright produced a slim, handsome catalog for the sale with an essay and original and new photographs. The estimate for the house was $2.5 million to $3.5 million. Its contents-furniture, artwork, and accessories, as well as Haddawy’s 1958 Porsche 356 Speedster-would be auctioned off afterward.

The observers in the room were tense that afternoon as a phone bidder went up against an audience member-a woman who within minutes took control and won at $3.186 million. The buyer had flown from South Korea to California to look at the house and on to Chicago to bid, but she declined to reveal her name. (The Wrights will not disclose the buyer, either.)

The offerings for the main auction that day were the most outstanding of the fall season, and the catalog was the most stunning yet for Wright. With an estimate of $9,000 to $12,000, Rietveld’s Zig-Zag chair, the first item in the architects’ section that Julie had been working on in October, sold for $21,000. The Garouste and Bonetti desk and chair, which had been photographed in the Wrights’ library at home, went for $50,000, more than double its high estimate.

Photograph: Courtesy of Wright and Brian Franczyk Photography |

| Most of the Garouste and Bonetti items for last December’s sale were shot at the Wrights’ house. |

A week later, with their fall auction season over, the Wrights were reassessing the past year and looking ahead. Their Modern + Contemporary Design sale in October had been disappointing. The material, Richard says, simply was not good enough. But Wright’s auction on December 3rd was its best ever, with consistently fine offerings.

The sale of the house was especially rewarding. “The property achieved a price that it would not have achieved in the local market,” Richard says. “It legitimized the process and met our goals, which were not tied to a specific price. They were tied to saying that this house needed to be marketed to the world.”

Next year, the Wrights will focus on high-end rather than midrange items and will take on more real-estate sales when the appropriate projects come along. By early December, ten potential sellers had made inquiries. There is more to be done at Wright-nothing there stays the same. “Julie and I,” Richard says, “are always about ideas.”

Photograph: Julius Shulman |

| M-house |

Right Now and Later

Devotees of the Wright auction house point out that attending the previews is like going to a modernist museum exhibition free of charge. The sales for the spring season should appeal to buyers with a range of interests and resources: Modern + Contemporary Design, March 25th; Important 20th Century Design, May 20th; Post War + Contemporary Art, May 22nd; and Mass Modern, June 23rd. Wright initiated Mass Modern, a sale of more moderately priced items, last year with the intention of introducing a younger audience to the period. Also to be auctioned on March 25th is the M-house (above), built in 2000 by the artist Michael Jantzen; a portable residence now in California, it looks like an intergalactic spaceship. See it on Wright’s Web site, www.wright20.com.

Previews at Wright, 1440 West Hubbard Street, are usually held from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. for a week prior to the sales. To or-der catalogs and check the preview dates, call 312-563-0020. As it says on the Web site, those who can’t wait for an auction can shop anytime through Wright Now. The items in this online gallery have been consigned for private sale or have not sold at auction. Those who would rather sell than buy can call or e-mail consign@wright 20.com.

The real action occurs at the main events, and at Wright’s major auctions, there is a free organic boxed lunch from Hannah’s Bretzel.

–C. N.