Rising above the north end of Jackson Park, the Museum of Science and Industry presides as the only major surviving building from Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Frederick Law Olmsted, the great landscape architect who designed the site of the fair, declared that it should forever be the “dominating object of interest” in the park.

Well, it’s not quite forever, but it has been 125 years. Now designers of the Obama Presidential Center want to build a 235-foot tower that would dwarf the museum and draw hordes of visitors to the serene green space around it. Various groups have been plenty stirred up about different aspects of the Obama Foundation’s plans: The center won’t drive enough economic development to the nearby Woodlawn neighborhood. Street closures will create too much congestion. Birds will have to find new homes.

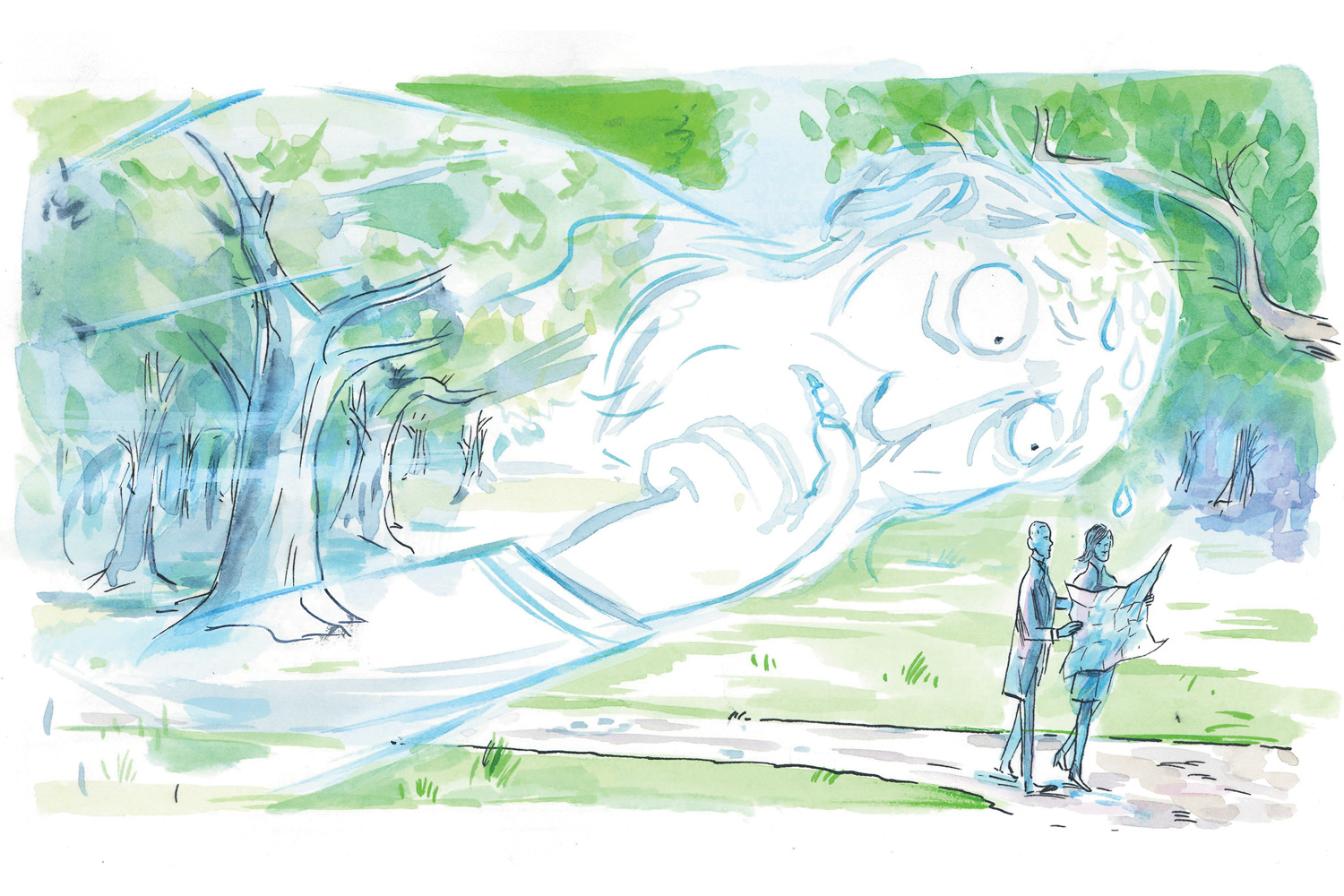

But the tower has become the focus of a battle between a particular subset of park preservationists and the foundation over what best represents Olmsted’s legacy: maintaining his intention that parks serve as “an antithesis to bustling, paved, rectangular, walled-in streets” or advancing his vision of them strengthening democracy and community.

“Most of us will have different interpretations of what Olmsted wanted,” says Juanita Irizarry, executive director of one of the groups fighting the plans, Friends of the Parks, which effectively halted the lakefront development of the Lucas Museum. “There is evolution, but those of us who believe in the tradition that made this park should be looking at the wisdom and guidance of that. The ultimate question is: Why should parks be used to develop real estate?”

To reinforce that point, Friends of the Parks points to a document filed with Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development by the Washington, D.C.–based Cultural Landscape Foundation, arguing that the tower would cast shadows over the parkland, destroy the serenity and seclusion of Wooded Island, and “reorient the visual and spatial experience of the landscape to focus on a single architectural element, one whose stark facades, reminiscent of a Brutalist idiom, would strongly contrast with its natural setting.”

Olmsted designed the park to be a refuge from exactly the kind of urban chaos the center would create, says University of Chicago professor W.J.T. Mitchell, who coauthored a letter, signed by over 100 faculty members in January, opposing Jackson Park as a site. “[Olmsted] had a very consistent vision, which was that the democratic urban park should not have monuments to great men.”

Yet the counterargument hinges on that very same point: Olmsted envisioned parks as gardens of democracy, common spaces that would draw together people of classes and ethnicities that were clashing elsewhere in 19th-century America. Of his philosophy on parks, he wrote: “You may thus often see vast numbers of persons brought closely together, poor and rich, young and old, Jew and Gentile.” So maybe he’d be OK with a monument to a great man who just happened to be the first black president?

That egalitarian ideal, says Obama Foundation CEO David Simas, is exactly what the center will bring to the park: “One of the leading drivers was the purpose of having a place where people could come together in a democratic fashion. In a real Olmstedian way, this is the way you build community. It’s our perspective that what we are proposing is consistent with the vision of parks as democratizing.”

Considering that up to 750,000 people are expected to visit the center and its proposed branch of the Chicago Public Library annually, the park will “unquestionably be more accessible with greater use,” Simas says. To bolster his case that it is most important to focus on the social functions of Olmsted’s creations, Simas points out that Jackson Park’s physical plan was long ago disrupted by the widening of Cornell Drive—which Olmsted designed as a bridle path—into a six-lane road. The center plans to grass over Cornell and replace it with a promenade along the West Lagoon “to honor the original carriage walk designed by Olmsted.” (Olmsted fans object to that plan, too, arguing that he intended for the drive to link the park to the periphery of the city.)

Besides, Simas says, lead landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh and center architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien have “obviously” taken Olmsted into account: “Jackson Park is a 500-acre park. What we’re talking about is 19.3 acres.”

The foundation has shown a surprising willingness, however, to modify its blueprints in response to public outcry. It abandoned plans to build an aboveground parking garage on the Midway Plaisance, which Olmsted designed to connect Jackson and Washington Parks. The designers also have ditched a water basin slated for the Women’s Garden. It’s conceivable that they could end up making the tower shorter.

Obviously, it’s impossible to know how Olmsted, who died in 1903, would have felt about a presidential museum in one of his parks. But, to borrow an essay title by Chicago author Stuart Dybek, you can’t step into the same street twice. A city is constantly changing.

Especially this one. It’s easy to imagine New York banning a tower in Central Park. That city, though, is a living museum. Chicago, on the other hand, has always rebuilt and reinvented itself, a civic inclination that goes back to the fire of 1871. As one of the youngest of the world’s great cities, we have less reverence for history because we have less history to revere.

So how much should the maxims of a 19th-century park designer tie the hands of a 21st-century president? Whatever Olmsted wanted for Jackson Park in the 1890s undoubtedly is going to make way for what Obama wants there today.