True to its profile, the Chicago Spire was conceived in a spirit of soaring optimism. In the spring of 2002, Christopher T. Carley, a local real-estate developer, learned that the architect Santiago Calatrava would be in Chicago for a lecture at the Art Institute. When Carley arrived, he sidled up to the front where Calatrava stood waiting for the event to begin. Carley introduced himself. Calatrava was gracious, then said he needed to give his lecture. The businessman sat down and plotted his next move.

As one of Chicago's most successful condominium builders, Chris Carley, the CEO of Fordham Development, has a strong head for numbers. But there's evidence that he has something else: a weakness for good architecture. As Calatrava spoke, Carley reveled in the architect's slide show—images of bridges that seemed weightless and buildings that appeared poised to move like living things. When Calatrava said good night to the audience, Carley jumped up and raced across Michigan Avenue to the BorgWarner building, where the reception for the architect was being held at the Cliff Dwellers Club.

Carley waited in the lobby for Calatrava to arrive, and when he did, he reintroduced himself. The express elevator came, and they got on. That's when Carley told the Spaniard, his captive audience for the ride to the 22nd floor, that he built luxury condominiums and that he was a big fan of the architect's work—not just the beauty of his structures but also the genius of the engineering that holds them up. Then he got to the point: Carley wanted Calatrava to design a marquee tower, something truly dazzling, for Chicago.

At the end of the line, just before Calatrava's handlers ushered him in to the reception, the architect took out a pad and scribbled down his phone numbers in Zurich, where he has his office, and in New York City, where he has an apartment. On another sheet, he drew a bird, signed it, and gave it to Carley. It was a brilliant way to end the conversation (Calatrava loves to give impromptu drawings away) and a lyrical beginning to what might become the tallest building in North America.

That was nearly six years ago, and things have changed. Carley is out and a brash new developer from Ireland is in. The design has been through four or five iterations. Scheduled for completion in 2011, construction began last summer under the cloud of imminent recession and without the security of a guaranteed bank loan for a project that is now estimated to cost $2 billion. And in spite of economic uncertainty, or perhaps because of it, the target buyers for the Spire's 1,200 luxury condominium units are not Chicagoans at all but rather an invisible jet set.

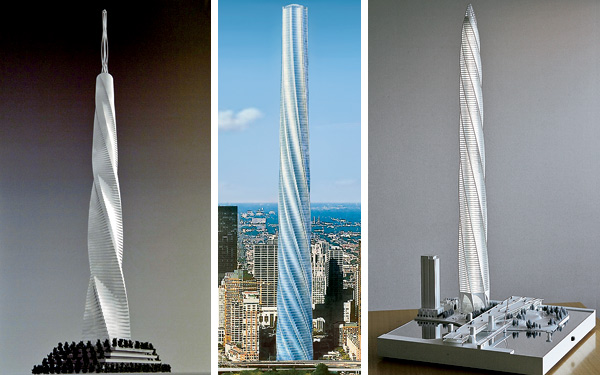

What hasn't changed is that this building—for a site at Lake Shore Drive and the river—has all the marks of a classic work of architecture. The Spire, in its current version, would rise seamlessly for 150 stories or so, with multiple helixes spiraling around its cylindrical profile, akin to an elongated, upside-down, perfectly formed twister. State-of-the-art reinforced concrete makes up the design's strong but invisible core. Steel outriggers around the perimeter would support a "unitized exterior wall system," which will appear to drape the building with an almost gossamer veil. At dawn, the tower's metal-and-glass exterior would gleam in the blaze of the reflected sun. By dusk, its silhouette, lit from within, would mark the edge of the city with a column of light, tapering gradually for all of its 2,000 feet until it reached its vanishing point in the sky.

"It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exultation . . . without a single dissenting line," wrote Louis Sullivan of the ideal skyscraper in his essay "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered." That was in 1896, when builders were straining to reach 15 or 16 stories. The Calatrava building would be ten times taller, of course, and it's a condominium tower, not an office block. But as a "proud and soaring thing," the unbuilt Spire appears to be the work of a true believer.

If you were contrary, you could say that the extravagantly elegant form of the Spire goes against the big-shoulders Chicago tradition of Sullivan's most timeless decree: Form follows function. After all, what's functional about a whirling dervish of a building that doesn't quit until it reaches uncharted heavens? The easy response is that buildings are costly, celebrity sells, and this is the high-rise that its starchitect, the dashing and urbane Santiago Calatrava, would appear destined to build. Carley naturally branded his building the Fordham Spire. But in the flush of press stories written when the design was unveiled, the developer admitted: "Everyone is going to call it the Calatrava anyway."

Calatrava has insisted that he didn't intend at the outset to design the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere. Nor did Carley, for that matter, who was evidently surprised if not shocked when he first saw the model in the architect's studio in Zurich. But Calatrava, who had studied briefly in Chicago after university, believed the site deserved such a thing. "It's where Lake Michigan meets the Chicago River, a kind of foundational place," Calatrava told me in a recent interview. So he created something "heroic," in keeping with the John Hancock and Sears towers. "These are all buildings that arrived at the limits of their time," he said. "Now we are trying to extend the Chicago model into the 21st century."

The glamour and the romance of the project were certainly Carley's strongest pitch in a meeting between the developer and the powerful Streeterville Organization of Active Residents (SOAR). Shortly after the project was announced, Carley invited the group's most influential members to his office, the first minuet in the dance to drum up the community support needed for any major new building in Chicago but especially for one of this scale. These meetings are usually a recitation of traffic flow and neighborhood impact—and normally as boring as the buildings that get built. Not this one. Carley spoke rapturously about the architect and his famous structures around the world, including the Milwaukee Art Museum, whose sun-shading screens, affixed to giant masts, move up and down like a seagull's wings.

"You could tell he was incredibly passionate about Calatrava and this whole design," said Gail Spreen, then an officer and now president of SOAR. With gorgeous renderings of the Spire tacked to the wall, Carley then launched into specifics: The building would house a luxury hotel on the lower floors with condominiums above, a total of 600 living units in all—which was, remarkably, fewer than allowed by the existing zoning. The garage would have a terraced garden as its "green roof," and a broadcast aerial, topping out at 2,000 feet in the sky, would make the building the tallest in North America, handily dwarfing the Sears Tower at 1,730 feet.

"I thought it was tremendous," said then alderman Burton Natarus, who met privately with Carley and Calatrava for a similar presentation. Natarus, whose blessing was desired for any project in his ward, was considered pro-developer to a fault over much of his 36 years in office; needless to say, he was enchanted, asking Calatrava to sign a book during their meeting and expressing admiration for the architect's bridge in Buenos Aires. As the project progressed, Natarus did due diligence as alderman—mainly addressing traffic issues, such as asking for access ramps on and off Lake Shore Drive to keep excessive traffic out of Streeterville—but it would be clear sailing for the Spire as far as the city was concerned.

"The financing was nebulous," admitted Natarus when I interviewed him much later. "But because of the magnitude of the project and who was involved and the notoriety of the project, we had to do everything we could to pass it." Which the plan commission and then the city council did for Carley's plan in a series of public meetings in March 2006.

Of course, the shadow of nebulous financing did not go away, and after a few months of public speculation about the project's future, a Crain's Chicago Business story on July 19, 2006, broke the news that the Fordham Spire had changed hands. Suddenly, the fantastic skyscraper's future was, for the moment, in grave doubt. Onlookers speculated that Carley had failed to secure financing in part because the site was too far from Michigan Avenue to attract a five-star hotel. The new owner—a little-known Irish company called Shelbourne Development—had bought the land (for a reported $64 million), which seemed like very bad news indeed.

Spreen, SOAR's president, was stunned. "Oh, my gosh!" she remembers thinking. "After this beautiful building, now what are we going to get?" In place of the Spire rose the specter of yet another hulking condo tower atop a massive windswept parking ramp.

In a press release the same day, Shelbourne announced that its owner, Garrett Kelleher, would proceed with the Spire design. Described as a Dublin-based investor who had lived in Chicago for ten years "beginning in 1986 when he arrived with $500 in his wallet," Kelleher affirmed his love for the city. "[Chicago] has a special place in my heart," his quote read. "Two of my six children were born here and it will always be my second home. I'm very excited to have the opportunity to contribute to the Chicago skyline." Streeterville had a revived Spire. And Chicago had a new real-estate mogul, a 46-year-old who had in fact made a tidy fortune as a loft rehabber in Bucktown a decade before.

For his part Calatrava went with the flow. He was fond of Carley. ("He's not just a rational developer," Calatrava says. "He's driven by his heart.") But Kelleher possessed audacity, an attribute hammered repeatedly by people who spoke about him. "He has the ability to take risk," says his Chicago-based attorney Thomas Murphy. According to Murphy, during a visit to Chicago on business Kelleher was approached by a Carley intermediary for gap financing. Kelleher said no, but countered almost instantly with an offer to buy the whole project. Carley, facing a payment deadline, agreed, reportedly keeping a stake in the project worth 15 percent of the Spire's profit. The deal took a week from beginning to end.

Shelbourne next announced that the Spire would break ground the following spring and that Kelleher would do so without a bank loan, rather tapping Shelbourne equity, estimated at $1 billion, to get the project under way. Beginning this way struck other developers and architects as pure folly—not just for Kelleher but for Chicago's precious lakefront—citing the risk of a half-built tower and no bank to finance the rest. Journalists raised the issue with Kelleher's growing phalanx of spokespersons, who answered with knowing smiles. "You'll see," they said.

In December 2006, Kelleher and Calatrava unveiled their first revised scheme. Still a spiraling tower, the design was now slightly wider from its base to the top; they scratched the plan for the hotel and filled the place exclusively with condominium units. The previous aboveground parking structure was replaced with an underground garage, a view-preserving gesture to its neighbors that would cost many millions. The base was an improvement but this wasn't the change that most people latched onto: The top no longer narrowed to a point but came to a blunt, abrupt end. Howls ensued. When SOAR's Spreen saw the model for the first time she thought they just hadn't finished it. The Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin described the new design as "straighter, flatter, less voluptuous, more Twizzler-ish," after the waxy licorice stick, and said the chopped-off top was a "sky-high letdown."

This sent Calatrava and Kelleher back to the drawing board, and they returned a month later, this time with a tapered, sufficiently spirelike top. But rumors circulated that Kelleher was shopping around several versions of the design, and the suspicion arose that he was trying to generate public support with pictures that were more fantasy than fact.

"It smells, and you know of what," wrote the Sun-Times architecture critic Kevin Nance.

It's hard to imagine what Kelleher had to gain by bullshitting anyone at this point, but stormy relations with the press continued. One of Kelleher's spokespersons chalked it up to culture clash. More to the point, Chicagoans, from curators to journalists to cabdrivers, claim architectural criticism as a constitutional right. And Kelleher didn't want meddlers and said so. "We're just getting on with it," he said at the time, as quoted by Lynn Becker, a well-regarded Chicago architecture blogger. "We're not really being led by media or journalists."

Those who know Kelleher say he can be charming. But his public reticence looked very much like stonewalling. He gave some interviews but responded to direct questions with platitudes. Finally he stopped answering interview requests—including mine, which went on for six months. "It's his land, it's his money, and he can do what he wants" was how one of his publicists explained his silence.

But Kelleher's aloofness wasn't the only thing that mystified. So too did his financing, or lack of it. Developers tend to be numbers-driven maniacs. They calculate costs to the last dollar. Banks typically require a condo developer to sell at least 50 percent of unbuilt units for any project, big or small, before they'll even consider a construction loan. Sometimes they ask for more if the project is extralarge: Financiers of the Trump Tower, for example, reportedly required 65 percent presold for a $780 million loan. Yet Shelbourne, which may need $1.2 billion in financing toward total costs of $2 billion, didn't even start selling until several months after ground was broken. It was blithely explained that Kelleher had enough equity in hand to start.

"It's an extremely risky way of approaching a project like this," said Dan McLean, a Chicago-based developer (who has condo developments near the Spire and could be construed as a competitor). McLean is not alone in this view. The basic numbers show that the project needs to sell at about $1,500 per square foot of living space to meet the industry's pro forma profit expectations. Other luxury projects in Chicago are getting $1,000 at most. Donald Trump asserted that Kelleher was committing "financial suicide." Others, more disinterested than Trump, do not disagree. And if the economics of the venture was tenuous last August, it's even tougher now. "Interest rates may be low, but banks just aren't lending money right now," McLean said.

Kelleher has seemed wholly indifferent to these outside judgments, or at least unwilling to discuss them publicly. When he finally spoke to me by telephone from Dublin, he was friendly if not entirely forthcoming. He acknowledged the unfortunate timing of a looming economic recession but insisted that it would not kill the deal. "In times like this people always revert to quality," he told me. "It is an incredible building. The standard and quality of design are second to none." Moreover, Kelleher expects the current credit crunch to resolve by the end of 2008. "The United States is a very resilient economy," he said. "Very robust."

While such rote blandishments don't exactly inspire confidence, the fact remains that Garrett Kelleher has performed real-estate magic before. Having started from scratch when he moved to Chicago in 1986, Kelleher, who says he is sole owner of Shelbourne, presumably controls a portfolio estimated to be worth more than a billion dollars.

He quit college before graduating (he attended a school in Pennsylvania on a tennis scholarship and later Trinity College Dublin) and came to Chicago, where he worked as a housepainter. He soon started his own painting company, and after six months began doing what his own clients were doing—buying old loft buildings and converting them into luxury condominiums.

"We were all highly leveraged then," said Bill Senne, owner of Property Consultants and sometime partner of Kelleher in those days. But Kelleher was as methodical as they come. On Cortland Street in Bucktown, for example, he bought the building that his painting company occupied. Later he moved to larger quarters on Elston and with Senne's help put a now fashionable restaurant called Jane's in the Cortland building. The timing was good in this renovation and a succession of others. Neighborhoods like Bucktown, the Elston corridor, and the Haymarket area on Lake Street, where he also bought and sold buildings, all went from rough to respectable in a hurry.

In 1996, Kelleher returned to Ireland, where he made a substantial fortune. Again he was methodical and discrete as he bought undervalued property and avoided publicity. When he surfaced as a major player—in 2000, the Irish newspapers reported breathlessly that he had bought a seven-bedroom house for 6.2 million euros—real-estate writers reported, presumptuously, as it turned out, that he had made his fortune in America. "The reality of the situation is that I did relatively little in Chicago compared to what I've done in Ireland," he told me. In fact, he returned to Dublin just as real-estate values there were about to shoot up. Ireland went from poor underclassman to the indispensable bridge between the United States and the resurgent European economic community. Multinationals—infotech, pharmaceuticals, financial services, and many others—took up residence there and sparked the "Celtic Tiger," as this new prosperity was called.

Kelleher told me that Irish real-estate prices still make Chicago's market look like the bargain basement. He cited his 2004 purchase of a rundown building on St. Stephen's Green—Dublin's Central Park—for 52 million euros (some $70 million at today's exchange). "It's now worth between $250 [million] and $275 million U.S.," he said. "That building in Chicago might be worth $50 million."

One deal in particular ripened Kelleher's pugnacity. On Moore Lane, a long-derelict stretch near Dublin's center, Kelleher bought a large plot in the mid-1990s. For most of the ten years that followed, his plan to build on the property faced legal obstructions, many from Treasury Holdings, one of the largest real-estate concerns in Ireland, which wanted to control all development in the area. "I was up against the local bully boys," Kelleher said of Treasury, an assessment with which others agree. "They called me 'the Yank' and said they were going to run me out of Dublin." But in 2004 he opened a 23 million-euro hotel on the land.

The lesson of Moore Lane was that Garrett Kelleher was not afraid of the big dogs as he was on the rise as a real-estate mogul. But then again, he has become a big dog himself. The London Sunday Times tagged him on its 2007 "Rich List" as the 165th wealthiest person in Ireland, with assets of 82 million euros, or about $120 million in personal wealth.

Chicago, as he found out, is different from the old sod. And last year when Shelbourne sought approval from the plan commission and city council, Kelleher grudgingly participated in the dog-and-pony show to cultivate political favor. Of course, he also had his not-so-secret weapon, his architect, happily running interference. While Kelleher sometimes spoke, Calatrava usually headlined any event designed to explain, promote, and woo. At one session with the Tribune's Kamin, Calatrava drew pictures and colored them with watercolors as he discussed the design. The episode was enthusiastically reported in the paper and the drawings ran with the story.

As the April presentation before the Chicago Plan Commission drew closer, a series of meetings made it seem like all Calatrava all the time. At one, an overflow congregation of SOAR's general membership, he spoke eloquently and drew pictures on an overhead projector. Calatrava visually compared the Spire's form to the spiraling interior of a seashell, an image that has been used to advertise the building. It was a building for the ages, he said. "It's like writing, or a poem."

"We were mesmerized," recalls Gail Spreen.

Even practiced hands were amazed by the performances. "I freely admit that I'm as subject to the cult of personality as anyone else," said Benet Haller, the planner overseeing the project from the city's side. Over the course of several meetings, he said, he'd never witnessed such enthusiasm for a condo development. There was applause from the politicians. Members of the press were often beaming.

By the time Shelbourne's version of the building was presented to the Chicago Plan Commission, any thought of official objection had dissolved. City Hall was so happy that it made at least one major concession: to include adjacent park district land as part of the building's zoning calculations. Shelbourne agreed to contribute some $13 million for DuSable Park's construction, which includes rent and plan development bonuses. Including the park's three acres was essential for the approval of the project, according to Thomas Murphy. The plan commission passed this and the rest of the Shelbourne scheme on April 19th, with a vote of 13 to 0. The city council sent it through without dissent on May 9th.

So here we are.

There's a great excavation going on at the lakefront. The sales center in the NBC Tower offers a view of the site. In January, Kelleher told me "there are currently 600 appointments made for prospective purchasers."

"We're selling to some of the wealthiest people in the world," said Dominic Grace, of the London-based realtor Savills, who received me at the sales center shortly after it previewed this past September. The place looks the part. Calatrava watercolors are framed as in a gallery. Calatrava-designed doorknobs and other details are displayed in vitrines of museum quality. The expectation is that buyers will come from other countries and that their Spire condos will be "second homes." To that end its sales force has embarked on a series of road shows around the world. Mentioned are Singapore, Shanghai, Dubai, Moscow, South Africa—these being the "low-hanging fruits," Grace said, before they go hard at Europe.

"There's sort of a melting pot that the world's rich fall into," Grace explained. "They all hang out in the same high-end resorts. Boats popping up next to each other—Cannes, St. Tropez, somewhere in the Caribbean. We're not pretending that we're going to get 1,200 of those people into the Chicago Spire. We're not pretending that all of those people will necessarily want to live in Chicago . . . not yet. But we think there are enough people who will be woken up to what a great place Chicago is." (For a more skeptical view of the international market, see Real Estate, page 76.)

Not to forget the architecture. "The Calatrava effect is very strong here," Grace added. "We hear it every day with prospective buyers. They are already totally in love with this building. They just want to be part of it. You might almost describe it as the irrational part of buying property." Nevertheless, Shelbourne insists that even these prices—some units may go for as high as $4,000 a square foot, which would set a record for Chicago—are low by world standards (London apartments can go for $10,000 a square foot). And for a 20 percent down payment you could see your investment appreciate by move-in time. That's the rational part of buying property.

By any measure, the building of the Chicago Spire is a daunting proposition, and as of presstime, bank financing had yet to materialize. But if it does go up, the skyscraper would certainly be a splendid addition to the skyline. It could also be good for the city in a lot of other ways, driving scads of new wealth from the Middle East, from China, and from Russia into the local economy. The Spire might even be the springboard that gets us the 2016 Summer Olympics, though the Spire sales force is also looking to the Olympics as a platform to sell its pricey condos.

Chicagoans grasp intuitively that architecture is more than money stacked high. But, what? Antony Wood, executive director of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat and a professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology—who is a fan of the Spire project—points to the global boom in tall buildings and observes that marquee construction no longer addresses what cities need or even what society at large wants. Rather, many such projects, he says, "take the iconic approach." They're unabashed monuments to the economic ambitions of Malaysia, China, Dubai, and other countries. "We are talking about buildings which become synonymous with a place even if they are not inspired by it."

Which is fine, but the Spire may make Chicago nostalgic for the old days, when Louis Sullivan believed that tall office buildings were monuments "to the best that is in your people," as he wrote, and "a sane and pure accounting of democracy." For him, big buildings symbolized upward mobility and growth. Sullivan's Auditorium, which attracted early fame to Chicago architecture, sought to bring grand opera to the masses by replacing the tiers of private boxes with many more seats, together in a common space. The Sears Tower, our enduring 20th-century icon, was built for the department store "where America shops."

Now, the Chicago Spire could be a symbol of the 21st century with its own not-so-hidden meaning: The superwealthy live among us, and they don't object to being admired in our fair city, perhaps even envied, but from a definite and inviolable distance.