The swing is loose and easy yet rattlesnake quick, and when the bat makes contact, the little white ball leaps away like a spooked cat. It soars into the blue sea of an Arizona sky, producing admiring murmurs from the handful of players awaiting their turns. The ball bangs off the chainlink fence some 400 feet away and drops onto the still-dewy grass of the outfield, where the ball chasers have just watched the shot sail over their heads as if it were a cruise missile.

It is only spring training, just the second day at that. Many of the players have not even reported yet. The 23-year-old standing at the plate, however, is taking nothing for granted—not his career, not the long, screaming liners he is blasting into the outfield during this early workout session, not the mere fact that he can stand here, healthy and alive, playing for the very people who had helped him through the darkest chapter of his young life.

He had been 18 when the mysterious fatigue hit. When his feet swelled so badly he had to stuff them into his spikes. When IV bags, not rosin bags, became his reality. When he was no longer an invincible teenager. Then, just when that ordeal had cleared the fence, came the hype. Anthony Rizzo, the next [name your Hall of Famer], the media wrote. Anthony Rizzo, the savior. When he finally got the call to the bigs, he started off hot but soon strained against lofty expectations. The loose and easy swing with the vicious quickness turned into an uppercut hack that pitchers quickly discovered they could beat with a good fastball. He flopped. And the media, and the fans, pounced.

Rizzo faced the hype again when he was dealt to the Chicago Cubs in January 2012. This time, he was referred to as the “cornerstone,” the “face of the franchise,” the Chosen One—handpicked by none other than Theo Epstein, the new Cubs president who had done the impossible in Boston and brought that long-suffering franchise and city not one but two World Series championships.

Epstein’s task? Simply to pick the exact right players to break a century-plus of futility and a goat curse that makes Boston’s so-called hex look like a short run of bad luck. Among Epstein’s first choices: Anthony Rizzo.

A couple of years ago, carrying all that weight might have crushed the young athlete. “Very few people are programmed to live up to the tonnage of hype that has been heaped on Rizzo, whose debut . . . spawned odes normally reserved for Grecian urns,” wrote Chicago Sun-Times columnist Rick Morrissey at the time.

But as he steps out of the batter’s box on this cool Mesa morning, Rizzo looks anything but daunted. Instead, he jokes with his teammates, giving and taking a playful jab on the shoulder, looking as relaxed and happy as a kid playing toss with his buddies. The serenity is no act. It is the key to a door that has slammed on him more than once.

The Mesa Complex where Rizzo and the rest of the Cubs prepare for the season doesn’t resemble a field of dreams. Fitch Park is a collection of diamonds and brick buildings that rise inauspiciously out of a landscape of modest ranch houses. For most of the year, it’s a place to walk the dog or have a picnic. On a slightly cool, achingly clear day in January, however, it is a baseball lover’s paradise. Balls thump mitts. The echoes of bats against rawhide crack like rifle shots. Young players in Cubbie blue play catch, run drills, shag fly balls. They even chat with fans—friendly banter, not press-conference-speak.

For at spring training—at least during the first few days—baseball players are not remote, larger-than-life figures. There are no wary-eyed ushers and security guards protecting them, scowling back potential interlopers who look like they might be trying to get too close. While there’s some separation between the fans and the players, it’s often only a waist-high chainlink fence, even a length of rope. Everyone from the manager on down seems friendlier, almost neighborly.

Anthony Rizzo more than most. A broad-shouldered, narrow-waisted six-foot-three and 240 pounds, he cuts a prototypical slugger’s figure from a distance. Closer in, he looks like an overgrown kid: boyishly handsome, with an expressive face, a leading man’s smile, and a mop of brown curly hair. For one of the biggest stars on the team, he has an aw-shucks air that most anyone will tell you is as sincere as a Lou Gehrig speech.

In an age of Lance Armstrongs and Alex Rodriguezes and Sammy Sosas, the image of the sports hero as good guy has been tainted unto destroyed. In Rizzo’s case, judging by the ballparks full of testimonials (and the time I spent with him at spring training), it’s hard to believe he is anything but a good guy.

“Obviously, he’s mature beyond his years,” especially given all he’s been through, says Epstein, who brought him to the Cubs. “I have never seen a young player gain such universal respect from his veteran peers. They can see right through younger guys, and they know if they are scared or if they are full of shit. They see that this kid is the real deal. He’s not just saying that he is here to help the team, he actually is.”

The roots of his maturity, people like Epstein—and Rizzo himself—will tell you, are the family he grew up in and the fires he had to walk through. For a sure-thing prospect, his path to stardom has been filled with enough trials and tribulations to fill an Old Testament chapter.

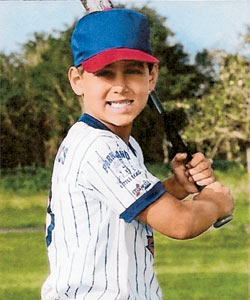

The younger of two boys, Anthony (Ant, his father calls him) was born on August 8, 1989, to Laurie and John Rizzo, a bartender and a security firm manager from the blue-collar town of Lyndhurst, New Jersey. When they moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, shortly before Anthony was born, they brought their accents (dead ringers for Tony and Carmela Sopranos’), their sense of humor (“My dad is the funniest person I know,” Anthony says), and their old-fashioned dedication to that all-American notion of the big, tight-knit family. Both John Jr. and Anthony were sports crazy from the start. “Even as a baby, Anthony loved to have the ball rolled to him,” Laurie recalls. “The boys grew up in a neighborhood that was all kids, and all the parents were friends, and they just played and played outside every day.”

And sometimes inside. John recalls chipping golf balls in the living room directly at three-year-old Anthony, who waited with an oversize mitt engulfing his hand. “Here’s this kid just turning three saying, ‘Daddy, hit me balls, hit me balls,’ ” he recalls, chuckling. “I said, ‘Ant, you gotta catch it. If I hit you with a golf ball, Mommy’s going to kill me.’ So I’d start chipping golf balls, and he’s catching them. And I’m getting pissed off that he’s catching every one!”

John suggested a “lightning round,” placing ten balls in a row and whacking them, one by one. “He’s [still] catching every one. I’m saying, ‘This kid’s got it.’ ”

His father wasn’t the only person who thought so. In the boys’ T-ball league, which John coached (among other sports), other kids jokingly asked for young Rizzo’s autograph. “A friend of mine who owned a trading card company came down here to visit,” says John. “He sees Anthony play, and he sits him down at the kitchen table and has him sign a napkin saying, ‘I, Anthony, give you the rights to all my signatures.’ ”

Basketball. Football. Roller hockey. Ice hockey. Stickball. The boys played them all. In Rizzo’s sophomore year of high school, he began to focus solely on baseball.

By his senior year, scouts came calling. One of them was Laz Gutierrez of the Boston Red Sox. Gutierrez brought the 17-year-old to the attention of Epstein, then the Sox’s general manager. Rizzo was “big and strong and physical,” recalls Jason McLeod, one of Epstein’s front-office attendants at the time. “He hit to left-center for power. That was something we were looking for.”

Even more impressive, McLeod says, was Rizzo as a person. “We took him to the Dominican Republic to see our facility there. It was really touching” to see how he handled the poverty he came across. “He was saying, ‘We’ve got to help these kids.’ He wanted to understand who they were and where they came from. And so we drafted him.”

When Rizzo’s family got the news, “we screamed,” his mother recalls.

The Red Sox drafted Rizzo in the sixth round but wound up giving him third-round money. “I told his agent, ‘The kid’s worth a million,’ ” John says. “The agent said, ‘Don’t overprice yourself.’ ”

Rizzo was assigned to the Sox farm system. He immediately rewarded the team’s faith in him. “He was having a very good month [in April 2008], batting .360, .370,” says McLeod. “And that’s when he started feeling a little different.”

It started with fatigue. As a boy, Rizzo could play a soccer game in the morning, go Rollerblading, toss a football, and then play baseball until twilight. Now, at 18, he felt the exhaustion in his bones after barely a couple of hours.

At first he put it down to the long days working out in spring training. “You’re on your feet for a long time, doing the same thing,” Rizzo says.

He also had trouble urinating. The information disconcerted his mother, but “he just said he felt run down,” says Laurie, who was distracted by her mother’s battle with breast cancer.

Fatigue notwithstanding, Rizzo got off to a strong start in the Red Sox minor-league system. He continued on a tear when the team’s farm club went on a road trip to Greenville, South Carolina, in April 2008.

But other odd things began to happen. In the space of a few days, Rizzo gained 15 pounds without changing his eating habits. “Then I started noticing my legs were really swollen,” he recalls. “From my hip down, everything was swollen. My toes. My legs. I didn’t want to say anything because I was doing so well.”

John, who was in Greenville to watch his son, had no idea. “The only thing I saw wrong was he sort of had a little limp,” he says. “But he always played so hard—I thought it was no big deal.”

Then one of Rizzo’s teammates called, asking, “Did you see Anthony’s ankles?” When he got his first look, John was shocked. “His ankles looked like they were water balloons.”

The team’s front office flew Rizzo to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to have specialists take a look. They initially thought he had a kidney infection. After a series of tests, they knew differently.

Rizzo’s mother was at his bedside in the hospital when he got the news. “The doctor said I had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” says Rizzo, “but I didn’t really understand. He said it’s a form of cancer. Once the word ‘cancer’ came out, things got real emotional.”

“I could hear his voice cracking” over the phone, Rizzo’s father recalls. “He said, ‘I’ve got cancer—not Hodgkin’s, not lymphoma—I got cancer. Am I going to die?’ ”

The family was stunned. “Hearing that was like somebody puts cinder blocks on your feet,” John says. “My mom passed away from cancer when I was in eighth grade. It was a two-year moaning hell. When you hear a loved one has it, your son, you want to just fall to the ground.”

Doctors explained that Rizzo had two tumors, one on either side of his pelvis. The good news was that the cancer had been caught early. The success rate for treating it was 97 percent.

“Can I play baseball?” Rizzo asked.

Sorry, the doctors said, not right now. He would have to undergo a six-month chemotherapy regimen. Then they would see.

He turned to his mother, who reassured him: “I don’t know why this is happening. It doesn’t make sense. But I do know that everything happens for a reason. And I know that one day down the road you are going to be able to help people.”

Rizzo was deeply grateful for one thing: The Red Sox had provided the best doctors and facilities. They introduced him to Jon Lester, a Red Sox pitcher who, two years after being diagnosed with virtually the same type of cancer as Rizzo’s, won the final game of the World Series. They even transferred his treatment to Florida so that he could stay with his parents.

“We were glad to do it,” Epstein says. “We were so devastated. He was such a young kid. He had just turned 18 at the time—first time living away from home, getting things off on the right foot. And then you have this happen. You couldn’t help but put yourself in the shoes of his parents and put yourself in his shoes.

“We wanted to make every resource available to him so he could beat it. We also wanted to treat him like family.”

Says Laurie: “They couldn’t have been any better to us. They had our backs the whole way.”

Rizzo tackled his treatment with the same ferocious determination he did sports. For his parents, he had one request. “I said, ‘I don’t want to get a bunch of sympathy,” he recalls. “I don’t want everyone going, ‘Oh, how are you feeling? To baby me. I just want to be normal.’ ”

Left unspoken was that he did not want to add to his mother’s burden as she dealt with her own mother’s cancer fight. “You never heard anything about [his illness from him],” says his brother, John. “He never really complains too much.”

And in the abstract, chemotherapy didn’t sound so bad. Get a few months of treatments, get well, and go play ball again. The reality was much starker. Long days attached to an IV. Four different meds, including two “push” injections. One injection was like “getting broken glass shot into your veins,” his father says.

“It wasn’t fun,” Rizzo agrees. He spent the next few months living at his parents’ house with his grandmother, who had moved there while she was going through her own cancer treatments. Rizzo had always been very close to his grandparents. “They were a big influence on my kids,” Laurie says. “They went to every single game that both of them had.”

In the days immediately following chemotherapy, Rizzo says, his body would shut down completely. “It would just be miserable. By the next week, I would feel OK, and I would try to go out and move around—shoot some basketball.”

He kept nausea at bay by sticking to a very limited diet. “The only thing I ate was my mom’s pasta and her sauce,” he says. “If I was really nauseous, I would drink a milkshake or eat brownies. So I actually gained weight and didn’t lose my hair. Not sure how that works.”

That fall, Rizzo’s parents were in a plane waiting to take off for Austin to watch their older son, who was now an offensive lineman with Florida Atlantic University, play the University of Texas Longhorns. They were also anxiously awaiting a call from Rizzo’s doctors, for the six months of chemotherapy were nearly over. “They were just about to tell us to turn the phones off when the phone rang,” Laurie recalls. “It was the doctor, and he told us Anthony was in remission.”

Her reaction? “I screamed,” she says, laughing. “I think the whole plane knew. I was yelling to some friends of ours in the back of the plane, ‘He’s in remission!’ ” But their joy would be tempered. Ten days after learning that he had likely won his cancer battle, Rizzo learned his grandmother had lost hers. “At least,” he says, glancing at the sky, “she knows I’m healthy.”

It was just a little practice game in Fort Myers, Florida, the last Instructional League event of 2008—as far away from the glory, grandeur, and drama of a big-league game as a sandlot field is from Wrigley.

But as Rizzo walked to the plate on that fall day, he could feel the adrenaline. Though he still had a few chemo treatments left, and his doctors weren’t thrilled with the idea of him playing, they had bent to his pleas. From a set of bleachers, his parents looked on nervously. His teammates, his manager, even the opposing team stopped to watch.

What happened next was like something out of a movie, his father recalls. Rizzo stepped to the plate, dug himself in, and waited for the first live pitch he’d seen in four months.

The ball sizzled in from the pitcher, Boof Bonser, a major-leaguer on a rehab assignment. And there it was: the sweet, smooth, relaxed swing with that quick rattlesnake snap. “The first ball he hits to the centerfield fence, almost out of the park,” Rizzo’s father recalls. “It was so emotional, even for the players on the other team, because everyone knew what he’d gone through. You could see a tear coming out of his eye when he was running around the bases.

“I think he got a couple of hits after that, and he did really good in the field,” John continues. “It was probably the best game I ever saw in my life, and it was just a little practice game.”

The next season, moving up a class in the Red Sox minor-league system, Rizzo picked up where he’d left off, belting more than 20 home runs. But the thought of the cancer returning hovered like a shadow. If he got past the first year, the doctors told him, he’d probably be OK. “So I was very paranoid,” Rizzo recalls. “I was always checking my hips to see if there was any swelling.”

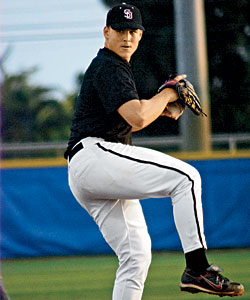

The cancer did not return. But Rizzo was dealt a different kind of blow. Epstein, who had become so close to Rizzo’s family, announced that he and his teammate Casey Kelly, a highly regarded pitching prospect and a good friend, were being traded. They were going to San Diego in exchange for the perennial all-star Adrian Gonzalez.

On the one hand, it was flattering—he, Anthony Rizzo, being tapped to fill the shoes of one of the game’s best hitters. But it was daunting to leave the Sox. “It was really hard for me,” Rizzo says. “I had been through so much with the Red Sox. They were all I knew, and it was kind of like family.”

It wasn’t easy for Epstein, either. “Calling Anthony to tell him he was traded was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do,” Epstein says. “I remember I was pretty emotional. I told him one day I would trade back for him. And I said, ‘Tell your parents that I hope they understand and that I still love you and your family.’ ”

Softening the blow was the fact that Jason McLeod and Jed Hoyer, both in the Red Sox front office when Rizzo was there and two of his biggest supporters, had already left to join the Padres.

Once again, Rizzo thrived. Playing for the Padres’ Triple-A affiliate, he scorched the league’s pitchers, hitting a blistering .452, with six home runs and 24 RBIs in his first 15 games. He did so well that buzz began to build. When was he going to be brought up to the big club?

The buzz turned into hype. The hype became hysteria. “He came up with about as much fanfare as any player I can remember,” recalls McLeod, now senior vice president of scouting and player development for the Cubs.

When the team finally did promote Rizzo, on June 9, 2012, you half expected him to walk “from the airport across the harbor to Petco National Park,” wrote the San Diego Union-Tribune columnist Nick Canepa. “The only question is whether he can handle the hype and expectations.”

At first he did. With a group of 20-plus friends and family watching, Rizzo struck out his first time up but then slammed a triple to dead center—a hit that just missed being a home run—and walked his next two times at bat. After a mere three games, a national sportswriter turned to the team’s manager, Bud Black, and asked of the player, who was barely 21: “He could become the face of the franchise, right?”

Rizzo’s father recalls: “They were treating him like a god. For his next trick he’s going to stop the Iraqi war and have world peace by next year. It was too crazy. It’s tough on the head when you got that kind of stuff going on.”

Sure enough, things fell apart quickly. “You could see his swing changing,” John says. “He started batting real tense. Every once in a while, he’d call me and ask, ‘What am I doing wrong?’ ”

“I saw a young guy who tried to do too much,” says Epstein, who kept tabs on his protégé from afar. “He got really uphill with his swing, which is what happens when you are trying to hit home runs rather than just hit the ball hard.”

By July 19, six weeks after Rizzo’s debut with the Padres, he was batting a dismal .149. He had struck out in more than a third of his at bats. In his last 25 big-league plate appearances, he’d had only one single.

Three days later, the heralded rookie, the can’t-miss savior, was sent to the minors. Rizzo was stunned. He “walked out of manager Bud Black’s office, a dazed look etched across his face, after learning he was headed back to Triple-A Tucson,” the Union-Tribune’s Don Norcross wrote.

In San Diego, the same people who had canonized him now savaged him. Rizzo tried not to pay attention. But the sarcastic tweets and daily newspaper stories got to him. “All these people were saying I was no good and I stink, and I’m like, They don’t know me,” says Rizzo. “They don’t know the type of person I am.”

It didn’t stop them—and, more ominously, some major-league scouts—from questioning whether Rizzo could make it in the big leagues at all, much less be a star. “There were a lot of veteran scouts watching him who said no,” Epstein concedes.

Rizzo had beaten cancer, but now his career hung in the balance. To this day, he can’t really explain what happened. “I was trying way too hard,” he told me one recent afternoon after practice. “It might sound a little strange, but to try at all in this sport is probably wrong, just like in golf. I was trying to get four hits in one at bat—to prove to everyone that I’m as good as they were saying.”

After the season ended, Rizzo returned to Florida to regroup. He began working on leveling out his “uphill” swing. And his mother reiterated what she had said before: Everything happens for a reason.

He knew she was right. He also knew that he had lost more than his swing. He had started to lose who he was. “I learned that you have to separate baseball from life,” he told me.

He closed his Twitter account. Stopped reading the papers. And in the Florida sunshine, he got to work.

Meanwhile, thirteen hundred miles northwest, the Cubs had pulled off a deal that thrilled Chicago. They announced that they had landed Red Sox general manager Theo Epstein, the most sought-after front-office boss in the league.

Having broken the so-called curse of the Bambino and brought Beantown two World Series victories, Epstein now turned his sights on a team with its own legendary curse and long history of frustration. One of the first steps he took was to reassemble the front office he had in Boston. Jed Hoyer and Jason McLeod were moving to Chicago.

At his first Wrigley press conference, in October 2011, Epstein told a mob of reporters that his goal would be the same as it had been in Boston: to build a perennial contender by stockpiling young talent through the farm system and trades. Speculation immediately centered on one of the game’s biggest stars and one of the hottest free agents on the market, a player who would cost a franchise an exorbitant, perhaps crippling, amount but would certainly make a bold splash: Milwaukee Brewers first baseman Prince Fielder.

The new Cubs president, however, went another way. He called the Padres. Would they consider parting with Anthony Rizzo? He hardly needed to ask. If San Diego hadn’t exactly given up on Rizzo, they harbored enough doubts that they were eager to unload him.

It was a gamble. But Epstein, Hoyer, and McLeod agreed that it was one worth taking. Rizzo was exactly the type of player they wanted: one who had enormous potential both as a player and as a clubhouse leader. “We knew him so well,” Epstein says. “We went through the cancer ordeal with him and saw him play in the minor leagues for the Red Sox. We knew his family, what kind of person he was. It was easy to bet on the person, his character. We thought, If he can make adjustments and restore his swing path, he could be great.”

When Rizzo got the call, he was elated. Grateful as he was to San Diego for the chance they gave him, he needed a fresh start. “They said, ‘We believe in you,’ ” recalls Rizzo. “That meant everything.”

To Rizzo’s father, it was the fulfillment of Laurie’s promise that everything happens for a reason. “It’s like all of this was planned,” John says. “Anthony does bad in San Diego, then Jed goes to the Cubs, Theo goes to the Cubs—they both know how good he is. . . . San Diego turned out to be a great training ground for him. It was more than just baseball. It was like, ‘OK, you’re going to learn humility, and now we’re going to send you to the Cubs, where you’re going to take off.’ ”

When the deal was closed last June, Epstein sealed it with a fitting reminder: “I told you I would trade for you someday.”

One of the first things the front-office triumvirate told Rizzo was to forget about his struggles in San Diego. “They named a few guys who started off badly in their careers and who went on to be Hall of Fame guys,” Rizzo says. “I’m not saying I’m going to be that by any means, but the reassurance was great to hear.”

As in San Diego, Rizzo started off in Triple-A. And as with the Padres, he tore the league up. In an almost identical set of circumstances, fans began to clamor for Rizzo to be promoted to the majors.

If there was hype in advance of Rizzo’s call-up in San Diego, there was near frenzy in Chicago. “Prospect Rizzo’s Imminent Arrival All the Talk at Wrigley,” blared one Chicago Sun-Times headline. “A baseball uniform, not a cape and an S-emblazoned Spandex suit, will be handed to Anthony Rizzo on Tuesday at Wrigley Field,” the longtime Sun-Times beat writer Toni Ginnetti quipped. “There’s nothing this 22-year-old phenom can’t do, if you believe what you’ve been hearing and reading. Rumor has it Rizzo flew in from Des Moines without a plane for his Cubs debut,” one columnist added.

Once again, Rizzo faced crushing pressure—and the question that had dogged him in San Diego: Could he handle it?

This time he was ready. It helped that veteran teammate David DeJesus took Rizzo under his wing. “I’ve been around guys who were in the same boat as him, with all the hype,” DeJesus told me after practice in Mesa one afternoon. “I wanted him to know that I was the guy who didn’t care about that. I just wanted him to learn how to respect the game. And everything that I’ve seen so far, he’s humble. He was humbled coming here. But being able to take that experience and learn from it and build on it—there’s nothing more valuable. And he has.”

On a humid day last July, in the tenth inning of a game against the St. Louis Cardinals, things did go right. The ball sailed from Rizzo’s bat into the stands with room to spare. It was his first walk-off (game-winning) home run—against archrival St. Louis, no less. Watching at home, hisparents “went crazy,” Laurie says. When Rizzo called later, “he was on cloud nine.”

As Rizzo rounded the bases, his father noticed something he doesn’t often see: his son flashing a smile. His teammates, who had poured out of the dugout, waited at home plate. Rizzo took a couple of big steps, then leaped. He hung there for a moment, almost as if he didn’t want to come down.

At spring training, when I ask Rizzo about what his mother told him the day he found out he had cancer—how he’d be able to help someone else—he says that he thinks about something that has nothing to do with baseball.

He mentions a meeting he had last December with a teacher at his old high school, Stoneman Douglas, in Florida. The event was the inaugural Walk Off for Cancer, a fundraiser for the Anthony Rizzo Family Foundation. (He had launched the foundation earlier that year to support cancer research, patients, and their families.) Rizzo discovered that a teacher there, Ronit Reoven, was facing the same illness and the same treatment program that Rizzo had undergone.

Rizzo met with Reoven and became something of a cancer coach for her. “He was such an inspiration,” Reoven told me. “My diagnosis was devastating. I had just had a baby. I was asking God, ‘Why me?’ I was bitter.

“And here he was, having been through the same cancer. He helped me get through a lot of the yucky weeks. Just hearing his voice—him telling me, ‘I know, I know what it’s like, but you can get through it.’

“Now here he is, 100 percent healthy. He’s doing his baseball. He’s back on his feet again.”

In the Hollywood version of the Anthony Rizzo story, he stays 100 percent healthy. The crippling fatigue, the odd swelling, the sudden weight gain never return. He fulfills every bit of his tremendous promise. And the walk-off homer he hits is to win the World Series for the longsuffering Cubs and their fans, not a meaningless game for another woebegone team out of the pennant race by midseason.

Even the corniest script wouldn’t include that ending this year—though, of course, nothing is impossible. The Cubs, under Epstein’s guidance, are still stockpiling players, looking for the next star to join Rizzo and the team’s other young phenom, Starlin Castro.

But even if things don’t go exactly according to plan, Rizzo knows now that it’s OK. And that, he says, is the real lesson he learned from his mother, the reason he went through so many struggles. “I had to learn how to make this game fun again,” he says. “And I had to remember that at the end of the day, I’m playing a game.”

Our last interview over, Rizzo picks up his glove and cap and lopes over to where another couple of teammates are running wind sprints in the early-afternoon Arizona sun. Grinning, without a word, he joins in.

He looks like he could run all day.