Photography Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

In 1922, a geologist and paleontologist from Danville named William Gurley commemorated his late mother with a major gift to the Art Institute of Chicago—about 4,000 drawings from his private collection; Gurley, the director of the Illinois State Museum, a natural history museum in Springfield, loved European art but could afford only prints when he began collecting. When he died, in 1943, his wife gave the rest of his stash, some 2,000 more pieces, to the museum, which found it difficult to assess immediately due to its sheer volume. It wasn’t until the 1980s that curators began thoroughly cataloging the donations—and found a rare sketch by Raphael (see number 5 on the following page), one of only a few works by the Renaissance genius then known to exist in the United States.

Just as that masterwork was buried among the Art Institute’s possessions, the Prints and Drawings collection, tucked away on the first floor of the main building, is a hidden gem with about 60,000 prints and another 11,500 drawings. Only a small sample is ever on display at one time in the museum’s general galleries; the rest of the works reside in the collection, where they are available for anyone to view in the Goldman Study Center by appointment. (The collection is open to the public from 1:30 to 4:15 p.m. Tuesday through Friday. Make a reservation in advance by calling 312-443-3660; the collection allows only four appointments per day, and visitors must be 18 or older.)

The Art Institute ranks with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art as having the most diverse prints-and-drawings collections outside of Europe, where the top museums—notably the Louvre, the Prado, and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence—own most of the world’s best examples of the arts. Albrecht Dürer was one of the first great printmakers, and the Art Institute has a set of his master prints. Produced in 1513 and 1514, three remarkably detailed prints—Knight, Death, and the Devil; St. Jerome in His Study; and Melencolia I—are considered the peak of the German artist’s work. The collection also comprises a wide range of works by Rembrandt, including his late religious prints such as The Supper at Emmaus; The Descent from the Cross; The Entombment; and Presentation at the Temple. Francisco Goya, the prolific Spanish painter and printmaker, narrowly avoided the Inquisition after making Los Caprichos, a set of 80 engravings, many of which bitterly mocked the church and the monarchy, and satirized the foibles of Spanish society. The Art Institute has a rare set of etchings that predates the first printed edition.

Requesting works to view can be intimidating—after all, where does one start? But curator Suzanne McCullagh recommends that novices relax and take an exploratory approach. “If you don’t have any sense of what you want to see, grab a great name and ask for it—you’ll find that usually we have it,” she says, adding that you can also narrow the field by subject matter or zero in on a particular medium (such as pastel, ink, or charcoal). When asked to pick her favorites, McCullagh chose eight pieces by some of art history’s most impressive names, spanning nearly six centuries.

EIGHT GREAT WORKS

1. PABLO PICASSO

1. PABLO PICASSO

Minotauromachia (1935)

One of just two works from the 20th century that McCullagh included among her selections, this etching by Picasso is the best and most widely known of his many Minotaur studies. This impression is the final proof before the published version.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “This is one of the most ambitious in scale of all his Minotaur studies. By this version, [the composition] looks almost as it will in the final, with great details like the girl’s candle illuminating the scene.”

2. ALBRECHT DÜRER

2. ALBRECHT DÜRER

Young Steer (ca. 1493)

Dürer, the famous German painter and mathematician, was among the first to elevate woodblock printing as a tool for creating art. This small ink sketch is noteworthy for how realistically he drew the emaciated bull, at a time when such detail was still unusual.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “The anatomy is very exact, and you worry about this animal. He really uses line to suggest the ribs, and the bones are visible through the skin.”

3. JACKSON POLLOCK

3. JACKSON POLLOCK

Untitled (1944)

Possessing the haphazard look of a Pollock painting, this drawing is actually rendered in ink—green, black, and bright purple—to achieve a calligraphic quality.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “It’s most

unusual for its coherence and its extraordinary use of color.”

4. PISANELLO

Sketches of the Emperor John VIII Palaeologus, a Monk, and a Scabbard (1438)

This pen-and-brown-ink work came from a sketchbook, most of which now sits in the Louvre. A closer look also reveals a distinctive bull’s-head watermark that helped date the work.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “Pisanello drew this for a visit by the emperor. . . . Because [the emperor] was short, he was often depicted on his horse.”

5. RAPHAEL

5. RAPHAEL

Upraised Right Hand with Palm Facing Outward (1518-20)

Probably a study for a portrait of Saint Peter found in the Vatican, this chalk drawing of a hand is on a short list of Raphael’s last known drawings before his death in 1520 on his 37th birthday.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “This is characteristic of his late drawing style—–very subtle, very structural.”

6. EDGAR DEGAS

Café Concert (The Spectators) (1876-77)

Degas depicts the scene of a crowded concert in brightly colored pastels. The complicated tableau includes details like the man in the center about to spill his beer and a singer visibly warm from the stage lighting.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “This piece just came in this summer and it’s a really fine example of Degas’s use of color.”

7. REMBRANDT VAN RIJN

7. REMBRANDT VAN RIJN

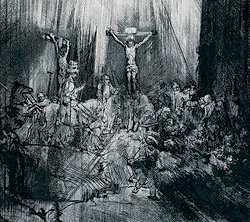

The Three Crosses (1660-61)

Rembrandt’s Crucifixion scene went through five versions. In the final, the artist covers some of the figures on the sides with an etching technique called dry point, obscuring them and creating a sense of chaos.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “There’s a lot of detail in this print. If you look at the figure on horseback in front of the cross, it’s clearly inspired by a medallion Pisanello rendered based on the horse-and-rider figure in his drawing [see number 4].”

8. JEAN ANTOINE WATTEAU

8. JEAN ANTOINE WATTEAU

The Old Savoyard (ca.1715)

Watteau was a French painter known for a light-hearted style that helped inspire the Rococo movement. The Art Institute has several of his drawings, including this example, a dignified chalk portrait of a Savoy street performer lugging his marmot box.

McCULLAGH SAYS: “You feel the elevation of this individual despite his anonymity.”

FREE FOR ALL

Get in free to the Art Institute during the month of February and year-round on Thursdays from 5 to 8 p.m. During the summer through Labor Day, the museum stays open an hour later, and Friday evenings are also free. 111 S. Michigan Ave.; 312-443-3600, www.artic.edu