In 1989, Nancy B. Jefferson, a political activist known as “the mother of the West Side,” stood before TV cameras downtown and dumped a box of oats into the Chicago River. She’d arranged the media stunt to protest the fact that the Quaker Oats Company didn’t use any Black advertising agencies for its media campaigns, despite the fact that African Americans made up a huge portion of its market.

Faced with an ugly public relations problem, the venerable Chicago-based business took notice. So did a Black entrepreneur and budding philanthropist named Willie Wilson, who owned a number of successful McDonald’s franchises and had just launched a televised gospel show called Singsation. In Jefferson’s protest, Wilson saw both a cause and an opportunity. Quaker Oats needed to demonstrate that it was committed to diversity, and Singsation needed a corporate sponsor. The company jumped at Wilson’s offer.

Advertisement

That story was related to me by Delmarie Cobb, a longtime Chicago political consultant, as an early example of Wilson’s canny business instinct. “Something set Willie apart from other donors in the business community,” Cobb said, “and that something was his amazing ability to leverage one opportunity into another.”

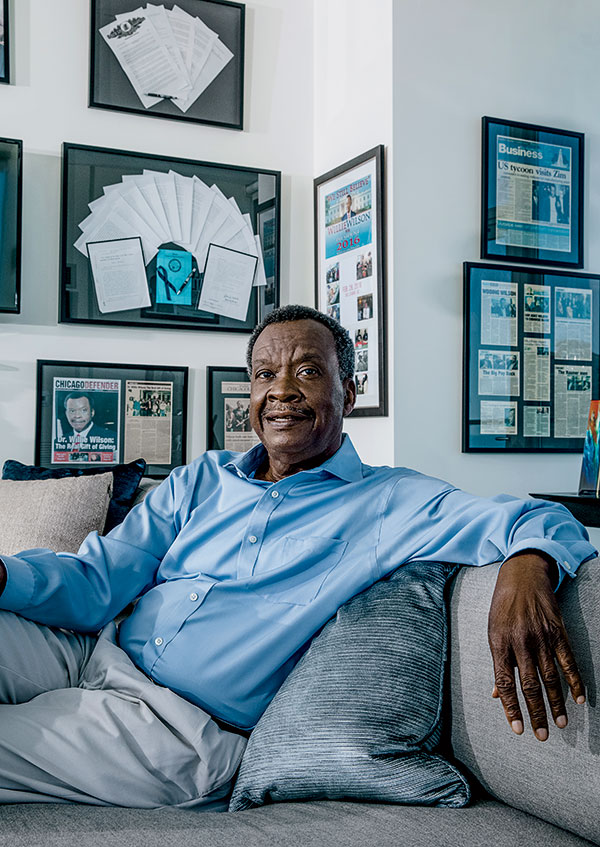

That Quaker Oats sponsorship helped get Singsation off the ground and eventually become one of the most popular gospel shows in the nation. (It won an Emmy in 2012 and is still on the air.) Wilson, 72, has long since left fast-food franchising and now owns a medical supply company that has made him a millionaire many times over.

He has also, in case you didn’t know, run twice for mayor of Chicago (he came in fourth in the 2019 election’s first round) and once for president of the United States (he got on the 2016 Democratic primary ballot in seven states, then dropped out and voted for Trump). He spent a considerable chunk of his business fortune on those failed bids and drew a great deal of attention for, among other things, handing out cash to churchgoers while in the midst of campaigning. In September of last year, he announced that he would run as an independent to unseat U.S. senator Dick Durbin. (He is now running under the banner of a newly formed party, a move that eliminates the cap on voter signatures imposed on major parties, thus making it easier for him to withstand challenges to his ballot petition. The name? The Willie Wilson Party.)

Cobb, who has known Wilson for decades, seemed to choose her words carefully when I asked if the candidate has a chance against Durbin: “He certainly is running on issues that are appealing to the Black community. We feel so often that our issues aren’t even being discussed. Willie is elevating a discussion that most people are avoiding.”

Given all this, was she planning to vote for Wilson in November? Cobb laughed, paused for a few seconds, and asked, “Are we still on the record?”

From the very beginning, Willie Wilson — self-made millionaire, evangelical Christian, sometime Trump supporter, son of Louisiana sharecroppers, lifelong philanthropist, reparations and civil liberties advocate, political street fighter — has been a hard man to pin down. Many people in Chicago’s church-centered African American communities adore him and view him as a perhaps eccentric yet deeply authentic and inspirational entrepreneur and spiritual leader. To some, a man who gives out money wherever he goes is a hero. “Many homeless people in Chicago know Willie Wilson,” says F. Scott Winslow, his friend and campaign spokesman. “They know him, and they love him. He never goes out without cash in his pockets.” Winslow speaks of Wilson with the reverence of a disciple. “He is a true Renaissance man. In 2020, for an uneducated Black man to be a Renaissance man is very unusual. Better than Bill Gates.”

But at the other end of the spectrum, particularly in the state’s political establishment, you have people who view him as a charlatan and an opportunist — people like Hermene Hartman, a publishing and PR executive with deep roots in Chicago’s Black community. “He’s trying to buy acclaim and fame with his fortune,” she says. “Here’s a man who doesn’t speak well, limited education, and so he tries to compensate, to come in like Batman to the rescue. And it’s bullshit. It’s politically driven, Republican bullshit. Self-aggrandizement and chest beating. Those ministers who are in his group — he pays them, he donates to them, he fixes the roof and the furnace, he buys things for their churches. He’s a generous donor, but it’s for people to follow him. That’s not leadership, that’s paid followship.” Hartman points out that her criticism of Wilson should not be taken as criticism of his work in the Black community. What enrages her, she says, is not the substance of Wilson’s platform so much as the savior-like, chauvinistic style of his public persona, a style she likens to “plantation politics.”

At the start of our first meeting, in January, Wilson was inscrutable. I’d arrived out of breath, having been given the wrong address by Winslow. It turns out that Wilson’s 46th-floor penthouse campaign office and pied-à-terre on East Wacker Drive (he also has a house in Hazel Crest, where he lives with his wife of 23 years, Janette) is directly across the river from the luxury high-rise where Winslow lives, and Winslow had given me his own address by mistake.

“You found us!” Winslow said as he took my coat before introducing me to Wilson, who was dressed in casual slacks and a button-down shirt and seated at a large table surrounded by windows. Polite but unsmiling, Wilson shook my hand and invited me to sit across from him. I’d noticed that when speaking to others, Winslow referred to his friend as “Dr. Wilson,” presumably a nod to the doctorate of divinity that, according to the biography on Wilson’s website, he received from the now-defunct Mount Carmel Theological Seminary, or to the handful of honorary doctoral degrees the bio also cites, including a doctorate of humane letters from the Chicago Baptist Institute International, which Wilson — who did not attend high school, let alone graduate from it — became chairman of in 2011 after helping rescue it from financial distress.

An assistant had brought Wilson a stack of employee checks to sign, and as I waited for him to finish, I mulled what question I’d open with. Certainly I wanted to know if he really thought he could beat the four-term Dick Durbin, which is a long shot at best. But honestly I was more interested in the Robin Hood aspect of this man, taking from the rich and giving to the poor — only in this case, he’s rich, and he’d gotten that way by selling Big Macs and rubber gloves. He seemed more like a fictional character than an actual person. Ultimately I decided to start by asking him about his background. He’d told his remarkable bootstraps story publicly before, but I wanted to hear it directly from him.

As strange as it might sound, Wilson might never have ended up in Chicago if he hadn’t, around the age of 14, contracted an STD. He explained this to me plainly, stating the fact without any embarrassment. “I was young and going back and forth with the young ladies,” he said. “And I got the VD.” He had left his home in Gilbert, Louisiana, in 1963, taking a bus down to Delray Beach, Florida, with 39 other boys, to look for work. His parents were sharecroppers, and until leaving home, he’d worked alongside them, picking cotton for 20 cents an hour, attending school two and a half months each year. When the owner of the restaurant where Wilson had found work got word of the boy’s diagnosis, he fired him, and Wilson headed back to Louisiana.

Wilson eventually wound up in Chicago, where an aunt lived. He remembers arriving at the Randolph Street bus depot with 50 cents in his pocket and no idea where to go next. He’d never used a phone before. “Down in Louisiana, we had no phones. But we did have a TV, and I’d seen this show about a detective. And I’d seen him on TV put a dime in a telephone. So I put the coin in and dialed my auntie’s number.”

That first year, Wilson took work where he could get it. He moved into a place on 18th Street on the West Side. When he ran out of money, he tried painting people’s houses with a friend. “We got a lot of work, but the only problem was, people wouldn’t pay us.”

This was around 1970, and Wilson, then 17 or 18, felt himself at a turning point. He had a brother in California and thought he’d head out there, but his friend’s mother mentioned that she’d heard they were hiring at the McDonald’s at 107th and Halsted. “I went there, and the first day they taught me how to cook hamburgers, mop floors, stuff like that.” Wilson said it was about as fun as it sounds, and he was planning to quit and move to California, but that same day, all the white managers were walking out on strike. The owner asked if Wilson knew how to run the restaurant. Wilson said that he hadn’t even worked one day, but the owner replied, “Well, you’re all we got.”

Advertisement

I asked him if he’d been concerned about the consequences of crossing a picket line.

“Nah, I didn’t worry about that because we didn’t have nothing like that in Louisiana. We just worked. What did I know?”

No bootstraps story is complete without a moment of truth. Wilson’s came in 1979, and like many, it was preceded by hitting rock bottom. As he tells it, he’d been working as a manager at McDonald’s for 10 years without a day off, and was having domestic problems (he married his first wife sometime in the late 1960s, though he didn’t tell me exactly when, saying he preferred not to talk about it). In his self-published 2008 autobiography, he describes how he got in a fight with his wife that turned violent. She threw an iron at him, he writes, and in response, he punched her. The police showed up and Wilson confessed. “I’m not a wife beater,” he told the officers, “but I did hit her. I don’t deny it.” The cops decided not to arrest him.

It was at that point, Wilson says, that he had the idea to contact Ray Kroc, the McDonald’s CEO who’d turned six California burger joints into a global empire, and ask for his own franchise. “I just called his secretary, told her who I was.” Apparently unimpressed by his credentials, she suggested Wilson wait till Kroc was back in town for a shareholders’ meeting, a few months away.

Wilson remembers going to the meeting and being surrounded by “a lot of white folks” vying for a moment of Kroc’s time. “There were no African Americans there or on the stage, but I went up and started shaking hands.” Wilson managed to work his way to Kroc and introduce himself. “I sensed I didn’t have much time. I told him I was a manager but I wanted to get a McDonald’s restaurant. I told him I’d been working for McDonald’s for 10 years and if I didn’t get my own shop I wasn’t going to be able to work there anymore.” Kroc asked him where he was from, and Wilson told him Louisiana, and that his parents were sharecroppers.

As Wilson remembers it, Kroc was impressed by Wilson’s frankness and invited him to a reception following the meeting. At some point, Kroc brought Wilson back to his office and called in his assistant. “I want you to give this young man here a McDonald’s,” Kroc said, adding, “Sometimes I know when I say things to you in front of people here, you say ‘Yes, sir’ but assume I mean another thing. But this one here, I mean.” He asked Wilson how much money he had to invest. Wilson told him he had none. Kroc thought about this for a moment, then said, “OK, we’ll fix it.” Not long after, Wilson owned his first McDonald’s.

“Your lucky break,” I said offhandedly.

He shook his head. “I don’t believe in luck,” he said. “See, luck don’t have no beginning. Luck has no foundation. I believe there’s gotta be someone or something behind me.”

For Wilson, that guiding force is his religious faith. It makes sense that Wilson would embrace a higher power to explain his unlikely story: “I believe God showed me favor to put me in the position I’m in. People like me, from my background, my race, don’t get where I am.”

Willie Wilson is such a fixture of Chicago politics today that it’s hard to believe his role in it began only in 2014. That’s when the incoming Republican governor, Bruce Rauner, who presumably saw in Wilson a figure with both business bona fides and influence in the Black community, appointed him to his transition team.

At the end of that year, Wilson decided to run for mayor, becoming one of several challengers trying to oust Rahm Emanuel. When Jesús “Chuy” García, who was a Cook County commissioner at the time, fared well enough in the first round to force the mayor into a runoff, Wilson found himself in an auspicious position: that of a former candidate wielding a valuable endorsement. John Davis, an aide to Wilson during his run, says, “We always knew that we had a decent and reliable base with many of the Black churches, and I think that’s what scared the opponents, particularly Rahm Emanuel. It shook him to the point where I personally saw Emanuel and Ken Bennett [Chance the Rapper’s father and an aide to Emanuel at the time] coming over to Willie’s penthouse to have conversations of how they could ‘work this out.’ ”

Wilson ended up endorsing García. He would later cite Emanuel’s 2013 decision to close 49 public schools, virtually all of them in Black neighborhoods, as key to his decision. “It was a slap in the face,” Wilson told me. “How many kids dropped out of school because of that?” Wilson has expressed an intense animosity toward Emanuel ever since, telling the Sun-Times he “should be locked up” for “white-collar crimes.”

The endorsement of García was revelatory for Wilson. At that moment, says Davis, “Willie became a political broker. It worked well in making him someone to be reckoned with in Chicago politics.”

Perhaps emboldened by his newfound influence, Wilson launched his improbable campaign for president just a few months later. Running as a Democrat, he was the only minor candidate to show up on the ballot in South Carolina’s key first-in-the-South primary. His experience campaigning there, he told me, was one of several factors that eventually soured him on the Democratic Party. He assumed that having made the ballot, he would be allowed to participate in the state’s televised debate, but he’d failed to attain the 5 percent polling threshold required to qualify. Whether he was aware of that and decided to try his luck anyway isn’t clear, but this is how Wilson describes what happened: As he was preparing to enter the building where the debate was being held, one of his campaign organizers was told by a Secret Service agent that he would not be allowed onstage and, what’s more, that fellow candidate Hillary Clinton had specifically given the instructions not to let him enter.

He said the incident degraded his opinion of Clinton — who’d already earned his reproach because of her support for the controversial Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which her husband signed into law in 1994 — even further. That Wilson spoke of the two grievances — one personal, one political — in the same breath suggests that for him the boundary between those realms is blurry. His positions are sometimes shaped by personal alliances and grudges — a circumstance that may have contributed to his decision to abandon Clinton and the Democrats in 2016 and, despite his public advocacy for such progressive initiatives as reparations and decarceration, vote for Trump.

In 2018, Wilson announced a second run for mayor of Chicago. He provided one of the more memorable moments of the primary during a debate in February 2019: The candidates were asked which of the rival candidates they’d vote for if they couldn’t vote for themselves. When it was Wilson’s turn, he paused, then said, “I would just do like Chicago politicians do and give myself another name and vote for myself.”

From the beginning of the race, Wilson’s candidacy was dogged by the controversy surrounding his cash handouts in churches where he regularly makes appearances and sometimes gives guest sermons. In August of that year, the nonprofit Illinois Campaign for Political Reform filed a complaint with the Illinois State Board of Elections demanding Wilson disclose the amounts of those handouts — an aide to Wilson told WGN-TV that the politician distributed close to $300,000 to 2,000 individuals in a single church giveaway — but the board decided in Wilson’s favor, ruling that because the money came from a nonprofit, Wilson hadn’t broken campaign-finance laws. A few months later, Wilson was defiantly back at it, giving away $25 each — sometimes in loose bills, sometimes in envelopes — to a line of congregants at the South Side’s Old Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, which he presented with a $2,000 check at the end of his visit. “I’ll die and go to heaven before I stop doing that,” he tells me of the cash giveaways.

The optics may not have been great, but Wilson ultimately won more than 10 percent of the first-round vote, finishing fourth and outperforming Illinois comptroller Susana Mendoza and former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas, among others.

Once again, Wilson found himself being courted for his endorsement, this time by Lori Lightfoot and Toni Preckwinkle, now locked in a runoff to become the city’s first female Black mayor. Wilson believes he went out on a limb by endorsing Lightfoot, given that his base consists largely of socially conservative Christians who, in his words, “were never gonna vote for a lesbian mayor.” Says Delmarie Cobb: “Lori did not have a relationship with the Black community. It was the white, progressive community that supported her. When [Wilson endorsed her], it gave them permission to support a gay candidate.” In the lead-up to the runoff election in 2019, Lightfoot accompanied Wilson to churches, and he even took her to a step-dancing party on the South Side.

When I asked Wilson how he came to the decision to endorse Lightfoot instead of Preckwinkle, his Machiavellian candor startled me. “I could have gone either way. But Lori was new. I figured she needed me more and that she’d be more grateful for my support.” Then he added, “Unfortunately, so far, I’ve been disappointed.”

Wilson’s two most important sources of education are the Bible and his mother. Regarding the latter, he says: “She always told us, ‘Wherever you go, take the Lord with you.’ ” Another maternal edict was “Don’t hate white people, always love ’em.” But she qualified that: “Well, first she told us, ‘Don’t trust ’em.’ ”

I didn’t ask Wilson if there’s a meaningful irony in the fact that Winslow, his most trusted aide, is white. The 60-something health care industry consultant, who is fond of dark trench coats and dark sunglasses, first met Wilson in the late ’90s, when Winslow was the CEO of Michael Reese Hospital in Bronzeville and was preparing to cut a significant portion of the hospital’s staff. “Willie got wind of the layoff and showed up with a bunch of ministers one morning,” Winslow says. “They occupied my boardroom. My secretary came running in, freaked out. She said, ‘There are a bunch of ministers in the boardroom and they’re not leaving until you meet with them.’ So I walked in, and the two of us introduced ourselves.”

Winslow tried to explain to Wilson the financial necessity of the cuts, and Wilson tried to explain, in turn, how the loss of those jobs would decimate the community. It was all very tense, Winslow remembers, and at one point Wilson smiled and asked, “By the way, did you see Nightline last night?”

Winslow had. The news program had aired an investigative report about racial discrimination at the oil giant Texaco. Several executives had been caught on tape demeaning black coworkers, and the CEO had apologized on the air. The company lost $1 billion in market capitalization.

Wilson asked, “Did you see that boy from Texaco? How bad he looked?”

“I did,” Winslow said.

“Oh, good,” said Wilson, “because if this layoff goes through, you’re next.” Then Wilson amiably shook Winslow’s hand and left with his ministers.

Winslow backed down from the layoffs.

Soon after, he recalls, he began receiving what he dubs the Willie Wilson Wake-Up Call. “Once you’re in his circle, he’ll call you between 6:30 and 7 every morning. He’s often on the treadmill. He’s just checking in. That list includes governors, the chairman of the board of McDonald’s, and it will also include policemen, regular people.”

Advertisement

It was Winslow who first suggested that Wilson get into disposable medical supplies. In Winslow’s recollection, the idea was hatched with an off-the-cuff comment he made during one of Wilson’s visits to the hospital. Winslow pointed at a pair of latex gloves that had been thrown into the trash and said, “The future of medicine is in disposable supplies.” Almost immediately, Wilson pivoted his fledgling company, which until then had been selling cubicle curtains, and business took off.

It was around this time that Winslow came to understand just how small the gap was between impulse and execution when it came to his new friend. Indeed, that early experience steeled him somewhat for Wilson’s precipitous dive into politics. When Wilson told him about his latest bid, for the U.S. Senate seat, Winslow was surprised, but not overly so.

Wilson had wanted to talk to Durbin about a “community issue,” Winslow says. He doesn’t remember what the issue was, only that Durbin didn’t call him back. So Wilson complained to Congressman Danny Davis, who, according to Winslow, then told Durbin, “You better return Wilson’s calls.” Wilson still never heard from the senator.

Wilson insists that the unreturned calls are not why he’s running. “I wanted to know what he was gonna do for the people of Chicago,” Wilson says. “I wasn’t calling for myself. I was calling for the people in my community. So I said, ‘OK, fine. I’ll run.’ If he would have talked to me about reparations, about crime, about the killing, I wouldn’t have thought about running.”

Winslow remembers Wilson announcing his intentions over dinner at a downtown restaurant in August 2019, somewhere between the entrée and dessert. “I’m going to challenge Dick Durbin,” he said, then calmly continued with his meal. Winslow says he put down his fork and thought, Here we go again.

“Willie Wilson’s here today!” I heard a woman say as I followed the candidate and his entourage into Logos Baptist Assembly in Roseland on a Sunday well before the pandemic hit. Virtually all the worshipers were Black, and most were over 50. The room was hot, full of singing and energy. At first I sat near the back, but Winslow spotted me and waved me forward. I took a seat in a pew near the front that was partly reserved for the hearing-impaired, but Winslow kept waving me forward, gesturing to the pew near the pulpit where he and the rest of Wilson’s entourage had installed themselves.

Then, shouting to be heard above the music, he introduced me to the person next to him: a middle-aged white guy in a purple velvet blazer and black cowboy boots.

Winslow said to the man, “This is the reporter profiling Willie. You two might know each other.” Then he asked me, “Have you met Mancow Muller?”

A confusing exchange ensued during which it became clear that, as an East Coast transplant, I didn’t know who Chicago’s famously abrasive shock jock was.

“He’s been the target of some controversy,” Winslow explained, leaning in closer. “But he’s a deeply religious person. He comes to church every week.”

I was going to ask Muller how he became a Wilson acolyte, but I thought better of it when I realized he was crying — evidently moved by the music and, presumably, by Wilson himself when he stood up to preach and then presented the celebrants with a posterboard check for $10,000.

Whatever you think of his handouts, one thing can be said about the money Wilson lavishes on churches and his campaigns: It’s his. Like his three earlier runs, Wilson’s Senate bid is entirely self-funded. He says he is not fazed by those who accuse him of running a statement race or contend that, deep down, he knows he can’t win. As he puts it, “I ran away from home at 13 with no education past seventh grade. And I made it. A lot of people would have thought that was impossible. People love to tell you what you can’t do.”

When I asked Paul Vallas, the former CPS chief and mayoral hopeful, what he thought of Wilson’s Senate run, he hedged. “Personally, I would have preferred he run for an office he had a better chance of winning, like City Council. That said, it’s always good to have contests.”

“Is that a polite way of saying you don’t think he can win?” I pressed.

Vallas laughed. “Listen, I served on the state legislature for [former Illinois senator] Phil Rock and I got to know Dick Durbin. I’ve always had a high regard for him. Very dedicated public servant and a good leader. People like Dick. But clearly there are a lot of people who are really cynical about the American political system and its ability to get this country running in the right direction. They’re coming from different spectrums, but they’re all appealing to individuals who have lost confidence and faith in our political institutions. There’s an underbelly of the country that wants change. I suspect that might be part of Willie’s calculus.”

Others I talked to echoed the idea that Durbin is basically untouchable and so why bother going up against him? “I’ve had conversations with Willie: Why not just be a kingmaker?” says John Davis, the consultant who’s worked with him on strategy. “Use your money and influence to be a kingmaker.” Wilson heard Davis out, but charged ahead with his Senate plans anyhow.

Hermene Hartman takes a cynical view of why Wilson continues to run for seemingly unattainable offices: “Because if he can’t be the boss, if he can’t be the leader,” he doesn’t want it. She adds, “I’m sure Dick Durbin is not shaking in his boots.” Shaking or not, the senator emailed his supporters in July after Wilson had donated $5 million to his own campaign. “We have to double our efforts,” Durbin wrote, “in response to this influx of campaign cash.”

In March, just before the state issued its stay-at-home order, I returned to Wilson’s penthouse office. He seemed eager to talk about the Senate race, saying his decision to run had put Durbin on the defensive: “He’s in the community now because I’m in the race. He has a commercial with Kim Foxx now.” Then, rehashing what he’d said in previous conversations about Durbin ignoring Black constituents’ concerns, Wilson imagined what he’d say to the senator: “I want to know what you’re gonna do for the people in Chicago, about reparations, about crime, about the killing. I want some answers about the killing. I want the killing to stop.”

I’d noticed that Wilson consistently refers to Chicago’s gang violence and gun deaths as “the killing.” He seems to savor the emotional starkness of the term. Prompted by this thought, I asked him to tell me about his son Omar, who was fatally shot in 1995 at the age of 20. (Wilson’s medical supply company is named after him.)

What shocked me about Wilson’s response was not the story itself but how he told it: flatly, his voice empty of emotion, his face totally composed. “My son was selling drugs. He’d been in jail. I try not to think about it anymore. I don’t visit his grave anymore because I think the Lord wants us to keep on going. But he was in jail, and his mother called me and I wouldn’t get him out. My daughter called crying, wanting me to pay bail. I wouldn’t do it.”

I asked him why not.

“Because I knew what would happen. Just what happened: He’d get out and he’d get killed. But they kept calling me again, and finally I called a lawyer and got him out. I made him get a haircut. I told him he could work at a McDonald’s. Then one day a guy came in the house. A deal gone wrong.”

Neither of us spoke for a moment. Then I said, “I can’t imagine anything harder.”

“I block it out,” he said. “Don’t think about it much. They wanted me to go see the boy who did it, picked out of the lineup. I wouldn’t go. Whatever the Lord has done, I accept it.”

By the time I saw Wilson again, in late March, the pandemic had subsumed virtually all discourse, public and private. He’d called a press conference outside a fire station downtown to announce that he was donating 10,000 masks to first responders, a few of whom were gathered around him, with fire trucks in the background. Standing on the periphery, I noticed a group of young women pass by, smile approvingly, and snap a photo.

In the weeks that followed, Wilson would become embroiled in controversy when he offered to sell a large supply of masks to the city and Lightfoot turned down his offer, claiming that he had asked to be paid in cash and would require much more time to deliver the masks than other companies. The episode seemed to mark a definitive rupture between the mayor and the former campaign rival who’d endorsed her. The two would become further estranged when Wilson publicly criticized Governor J.B. Pritzker’s stay-at-home order, saying it restricted “constitutional rights.” By the start of June, when the city was convulsed by protests and looting in the wake of the George Floyd killing, Wilson expressed open disdain for the mayor and the governor, telling me in a text that they had “failed miserably” to adequately address the unrest.

Advertisement

My original plan in reporting this article had been to travel around the state with the Wilson campaign to get a deeper sense of both the man and the political climate in which he’s running. When the pandemic struck, I wondered if Wilson would be able to adjust to this new landscape; he seemed to thrive on the fervor of crowds. It didn’t surprise me, then, that as the shutdown dragged on, Wilson aligned himself with the conservative-backed push to reopen more quickly, at least where houses of worship were concerned, going so far as to offer to pay the fines for any church penalized for violating state orders. If liquor stores were essential services, the argument went, how could churches not be? (The scientific answer, it didn’t take much research to learn, is that churches are almost perfectly designed for viral transmission: enclosed, often poorly ventilated, and filled with people singing.) Governor Pritzker would eventually allow churches to reopen, albeit with strict occupancy and social distancing recommendations.

Few were observing those recommendations when I accompanied Wilson to the Metro Praise International church in Belmont Cragin in late May. Most of the pews were filled, and only half the congregants had masks on. Almost all were spiritedly singing as young children scampered between pews and rolled around on the floor. Wilson, not wearing a mask, spoke for about 10 minutes about practicing faith in a time of fear.

Later, while talking to reporters outside, he donned an N95 mask. I stood a few feet from him and tried to think of a question I could pose that would help me understand his logic in promoting what seemed to be patently unsafe gatherings.

“Aren’t you afraid?” I ultimately asked. “For yourself? For those you’re trying to help?”

Amid the roar of passing vehicles, he replied, “I’m not afraid. The Lord will protect us.”

Did he truly believe what he was saying? Or was he practicing a bit of political theater? I tried to find the answer in his face, but it was no use. I couldn’t see behind his mask.

Comments are closed.