Snapping a funhouse-mirror selfie at Cloud Gate or strolling beneath Calder’s Flamingo might be the closest any of us gets to truly engaging with large-scale public artwork. But Chicago filmmaker Jack C. Newell has long wondered if there is a more reciprocal way to create public art.

“Usually public art is a government entity or corporation choosing a single artist to put their piece of art in a public space,” says Newell, a Lake View resident. “The only thing that makes it public is it being in the public sphere. Could we make a piece of public art that’s actually made by the public?”

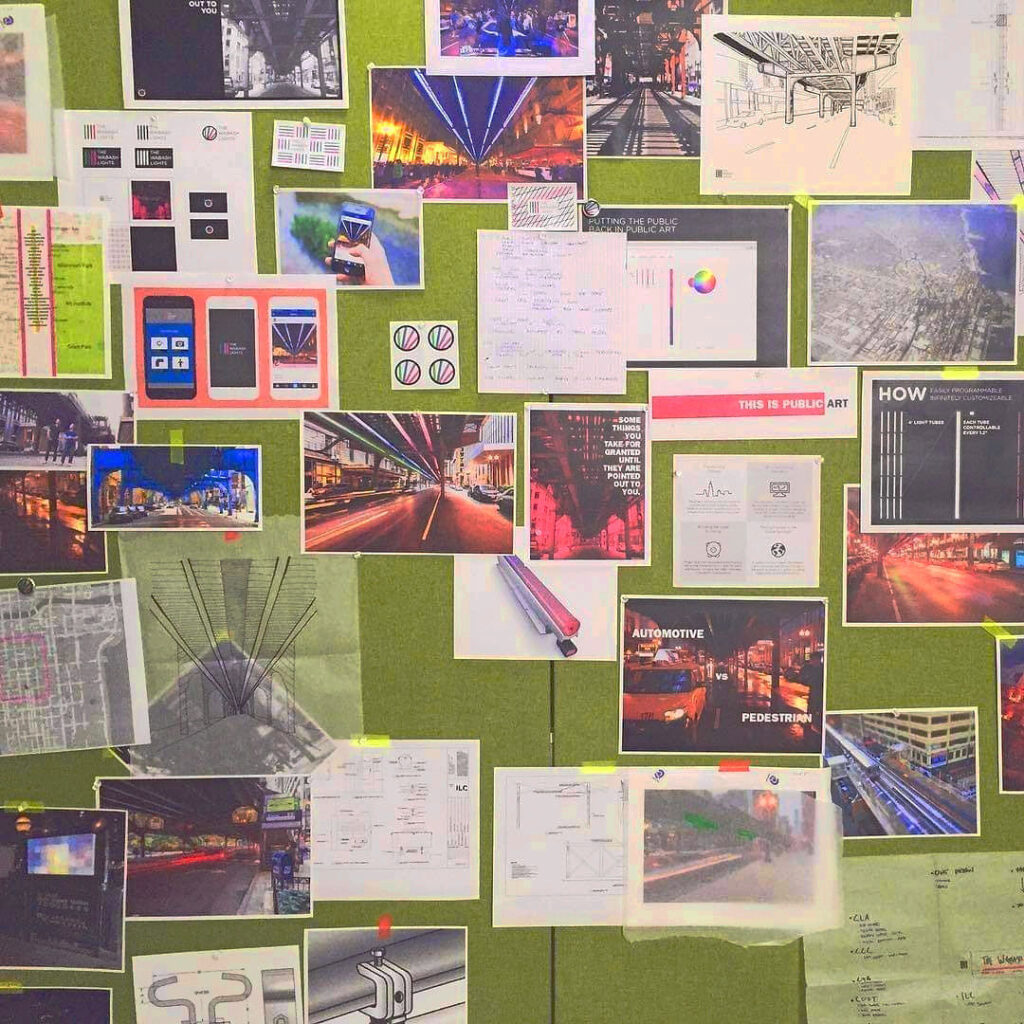

He first posed that question more than a decade ago. By 2014, he had an answer: The Wabash Lights. Ten years, two Kickstarter campaigns, one beta test, and countless meetings later, it’s about to become a reality. Underneath the L tracks along Wabash Avenue, between Madison and Monroe, Newell and his team will install four parallel 50-foot stretches of custom-built LEDs, which the public will be able to temporarily affect by scanning a QR code. The activation is set for the week of August 12 (exact date TBA).

“We’re building a museum now,” says Vinod Havalad, Loop resident and board president of the eponymous nonprofit organization created to realize The Wabash Lights. “The lights are the canvas — and you or me or my 7-year-old daughter become the artists.”

“We wanted to find a way to put the ‘public’ in public art,” Newell says. “That’s our slogan, and that’s how we landed on LED lights, because they’re infinitely programmable and interactive.”

Those passing the installation will find a QR code on street level which, once scanned, will pose a short series of prompts to let you choose a pattern and a speed that triggers a new, temporary light show.

That simple use by anyone on Wabash Avenue is just the start. “We level up from there,” says producer/director Newell, 42. He and Havalad, 43, envision endless opportunities for more detailed collaborations — for example, they’re already in conversation with the School of the Art Institute to let their students design more elaborate under-L auroras.

“We could partner with organizations or artists and basically give them the opportunity to take it over,” Newell forecasts. “That could mean partnerships with the CSO, or it could be another Lollapalooza stage. You basically plug the lights into their sound board, and it would become a visualizer. The opportunities become myriad once the installation happens.”

Of course, none of this is cheap. The two men report that completing the entire Madison-to-Monroe block — which the organization aims to do by the December holiday season, if they can raise the money — will cost $500,000. Phase 1 will fill in the first 50-foot stretch, just in time for its coming-out party for the Democratic National Convention. Funding for this initial phase comes from a variety of sources, including private donors, Comcast, and Gertie, a civic and cultural organization.

“This August, when a bunch of people are going to descend here for DNC, it’s a unique opportunity to showcase the city,” says Havalad, also a pediatric critical care physician at Advocate Children’s Hospital. “We want people to say: Here’s a beautiful city on this giant body of water with really exciting art, really exciting culture, and it’s a hub for innovation in tech and biomedical spheres.”

As the project’s long gestation indicates, money wasn’t the only hurdle. Although Havalad reports that city officials have always been enthusiastic — starting with the Rahm Emanuel Administration, which ran City Hall when this idea was born — multiple organizations had to be involved, including, of course, the CTA and the Chicago Department of Transportation. It took time for everyone involved to wrap their heads around the vision, and then to brainstorm solutions to any impediments.

To eliminate possible hazards, they set various restrictions on the project. For example: Any given stretch of the lights will end 30 feet before an intersection with traffic lights. Furthermore, the lights will not enable hyperactive flashing that might induce a seizure.

The designers also had to be concerned with condition factors, such as tolerating winter ice and sweltering heat, along with constant tremors from the trains rumbling above. The Wabash Lights team collaborated with San Francisco-based Looking Up Arts, an organization that specializes in large-scale art installations (think Burning Man), to design and custom-build the materials — not just the LEDs themselves, but metal clamps, nylon bolts, and rubber vibration-suppression pads.

In addition to creating a piece of vibrant interactive art, The Wabash Lights team aims to help revive downtown, which took a big hit from the pandemic. Currently, visitors encounter multiple vacant storefronts in the district, including on the very stretch of Wabash Avenue soon to be illuminated by this project. The hope is to increase culture-driven foot traffic by drawing curious individuals who might linger as they interact with the project.

That’s one of several factors that got the attention of Gertie, the culture-minded civic group headed by Pritzker family member Abby Pucker. In addition to “beautifying existing infrastructure,” Pucker says, “what appealed to us was the location, to revitalize the space post-pandemic. The Wabash Lights is something we wanted to support financially because we see the potential for long-term impact.”

“Chicago’s at a tipping point,” says Newell. “This project wouldn’t make sense if the Loop were lost — but we’re at a really key moment right now. It needs a shot in the arm, and we think The Wabash Lights could help.

“The interactivity of this project is the next step, in our minds, of what public art should be and can be,” he says. “We’re not defeating hunger; we’re not curing cancer. But the arts are important, obviously. It can open up new pathways in terms of how people view their city. When we get into CPS and we’re able to involve kids in STEM and STEAM programming, they realize: ‘Hey, I can actually affect my world.’ ”