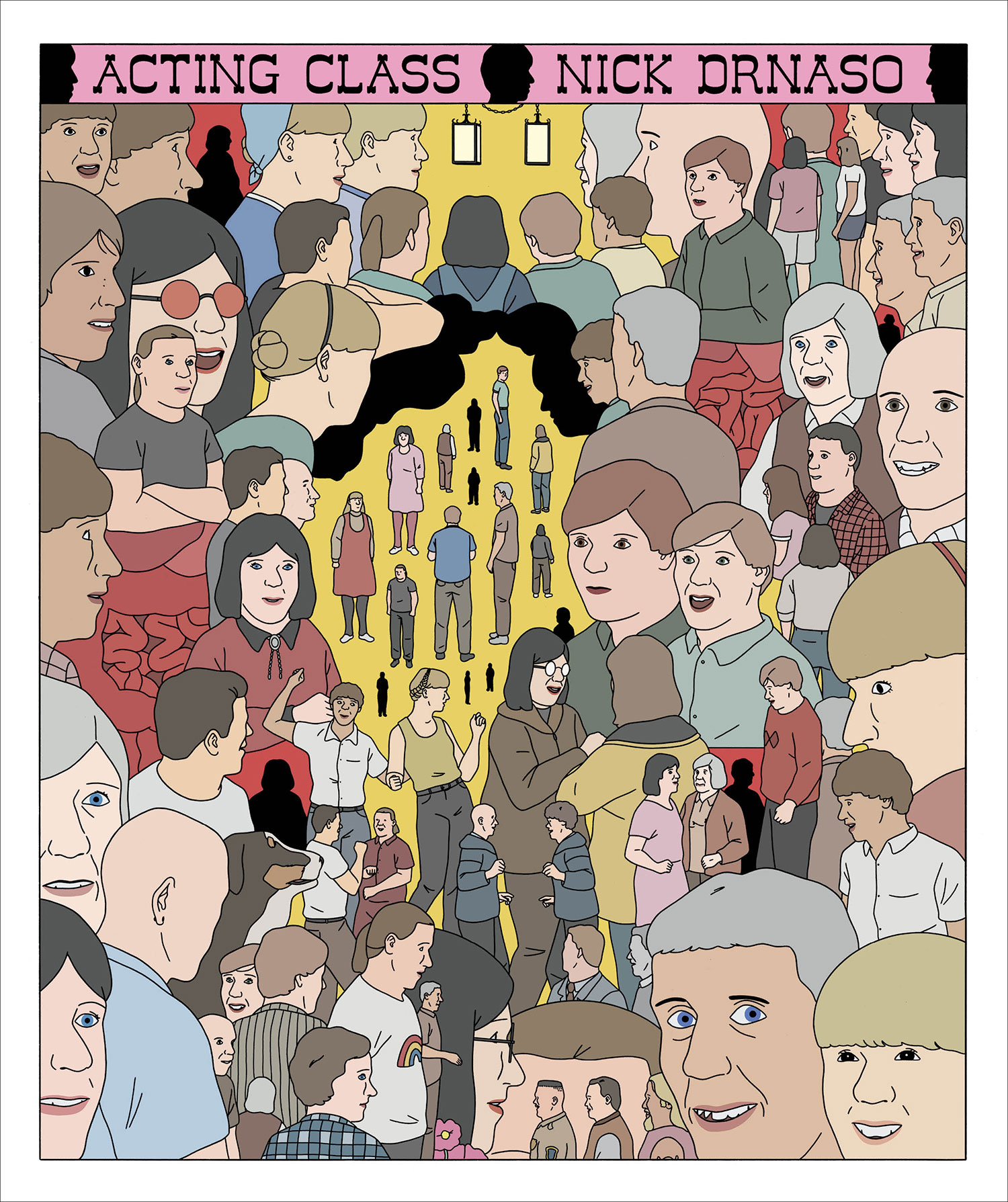

Few artists capture the mundane brutality and brutal mundanity of American life with the gimlet accuracy or muted affection of graphic novelist and Columbia College grad Nick Drnaso. His 2016 debut Beverly explored the wastes of suburbia through the eyes of its disenchanted teens, and his 2018 follow-up Sabrina took readers down the queasy rabbit holes of conspiracy theory.

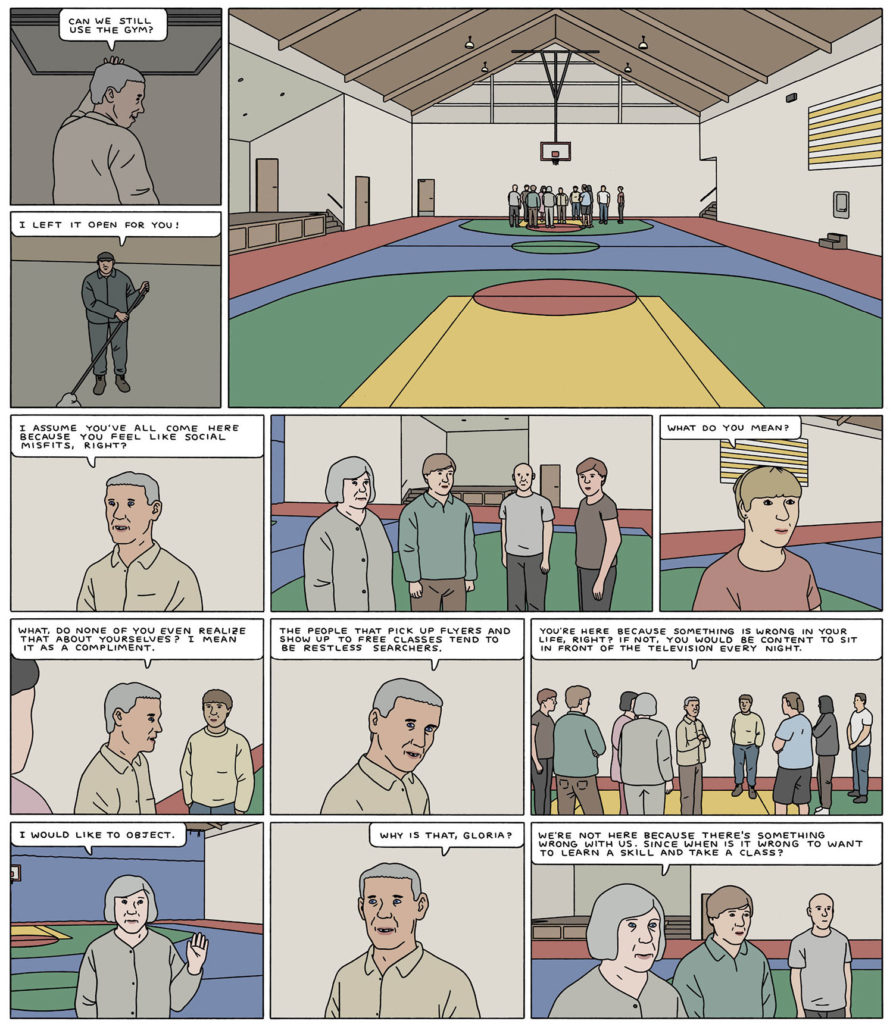

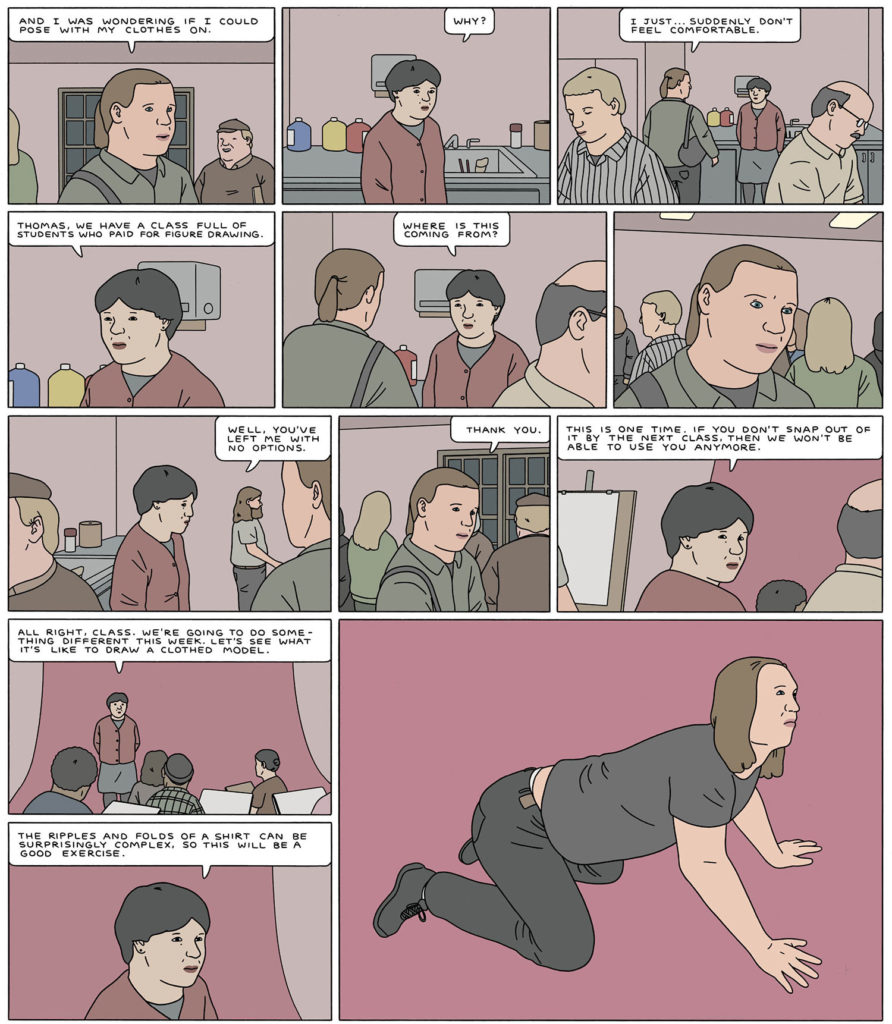

In his third graphic novel, the disquieting Acting Class, the Chicago-based Drnaso once again depicts the disconnection and desperation of his everyday characters with visual and verbal aplomb. Released by the Montreal-based Drawn & Quarterly in August, Drnaso’s latest book evokes a Daniel Clowes-meets-David Lynch vibe, unfurling in a flat and affectless Chicago-area setting. Panel by panel, ten lonely people drift into a community center workshop run by a mysterious and manipulative man who gives his name as “John Smith” and who warps their lives in dreamy and disturbing ways.

In Acting Class, Rayanne says to her 3-year-old son Marcus, “You don’t know it, but you have something that adults waste their lives looking for: total presence. Being alive isn’t that complicated.” Part of what art offers its practitioners is a connection to a certain child-like consciousness. When did you realize you wanted to be an artist and writer?

This sounds naive saying it as an adult, but as a very young kid, just (being) the person who could create things that couldn’t really be explained, they could be written about and dissected, but the mystery of it — there was a lot of intrigue in that. I’ve still hung onto that, even though the curtain has been mostly pulled back and it’s a lot different when you’ve gone through art school and you have more perspective on the life of an artist. It becomes a lot less mysterious. But luckily, it hasn’t taken away from the day-to-day enjoyment of that process, though that’s always a worry. There’s an arc and things don’t last forever.

You grew up in the southwest suburb of Palos Hills. How did your childhood and youth in that landscape inform your choice of topics now?

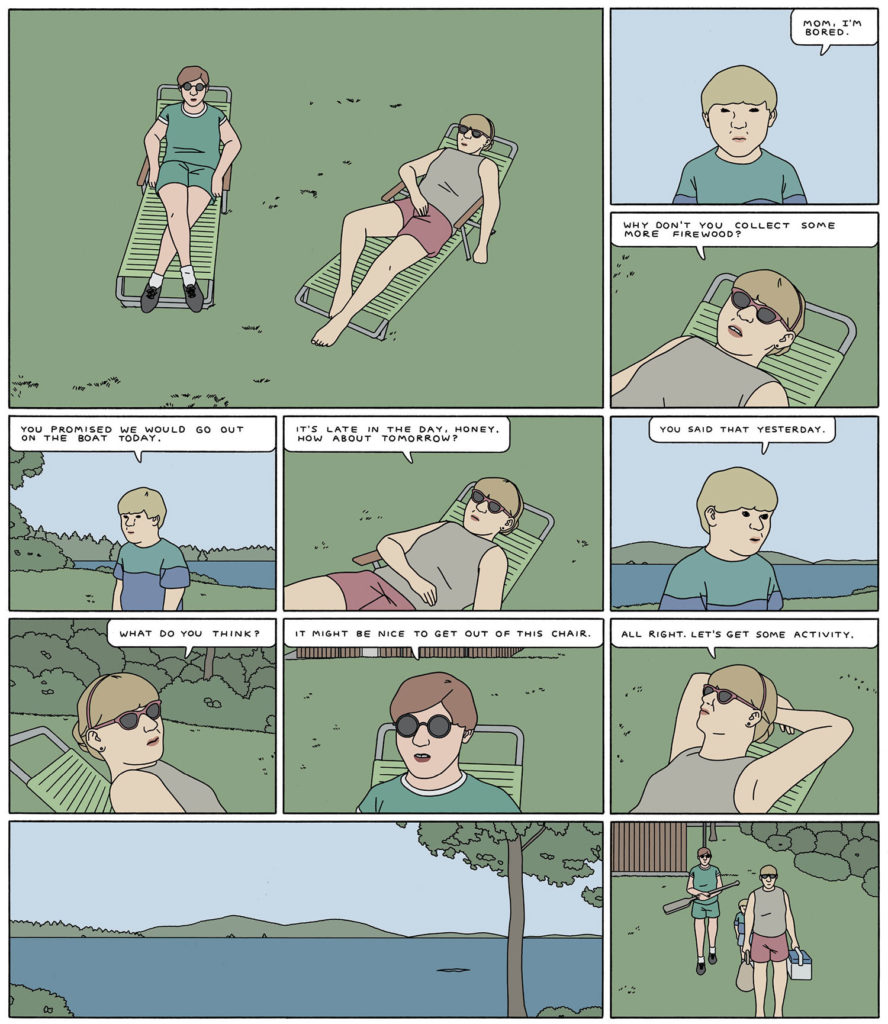

There’s a strong visual influence. I don’t really know how to manage space in another way. I just went to the UK and I was thinking as I was walking around and looking at the winding hilly roads and the alleys and things that I wouldn’t really know how to interpret that into a comic if I had to. The perspective is very obvious in a grid kind of place like Chicago. The houses are all mostly in a line and you can follow the perspectives as you’re walking around the streets, and that led into the way that I depict things.

Culturally, I guess with my first book, there was a conscious decision when I was in my early 20s. My memory of this place hasn’t been diluted by nostalgia or selective editing and memory. So, I should try to do this thing that depicts a certain world that I know because I don’t have enough life experience to write about anything else yet. That was my decision, at least for my first book, Beverly. Since then, I keep trying to branch out, but it circles back to that world, and maybe it would feel false to pretend that it’s not a part of my life experience.

Your work has a cinematic atmosphere in terms of the dialogue, all you have the characters leave unspoken, and in the way you frame your shots. You feel as much like a director as you do an author or an illustrator. What films do you consider as influences, if any?

Visual language seeped into my sensibilities when I was a kid more than books or comic books or static visual art did, even animation. When I look at my approach to composition from panel to panel, it does feel like someone holding up a camera.

I forget how impactful The Shining was, which I saw when I was probably too young. But even from the earliest age, that kind of clear approach to storytelling, slowly moving through space, was appealing. The clear depth of field and the stark perspectives that Kubrick is known for were also really appealing to me. As an adult, Kelly Reichardt is probably my favorite. I come back to her movies all the time, just because as I get older, a lot of movies just seem too bombastic or too macho for me. It’s amazing that her movies exist. They feel more like books or something; it seems hard somehow to get that kind of thing up on a screen.

You’re deft at balancing text and image in your work, but have you ever done, or thought about doing, a book that is either all text or all images?

I play out certain scenarios probably too much in a nervous, anxious way. I’ll often think about what’ll happen if I lose the ability to draw or the ability to see or if there’s some hindrance and I have to rethink what I do. I would probably be more likely to write a novel then write a completely wordless comic or to become a painter or something. I think I’m realizing that I enjoy the drawing day to day, but the story is really—I have to land on something that I’m invested in narratively.

All of the characters in Acting Class are searching for something. What are you searching for? What do you hope to find in your life?

I think this is maybe like a, not a midlife crisis kind of book, but I think there was a sense when I was younger that art and making art was all I needed and that was going to be the main purpose of getting up in the morning and not succumbing to depression or just to inaction. Now, it feels like that might be changing a little bit. My wife and I don’t have kids. I have a circle of friends, but there are vague themes of religion in the book or just finding your tribe. I think it’s a little weird not to have that, to just feel very disconnected from a community.