Arnold Voketaitis sang 14 seasons with the Lyric Opera, mostly in what he describes as “intermediate” roles — the priest in The Magic Flute, the police commissioner in Der Rosenkavalier, Dr. Grenvil in La Traviata. Such is the fate of the bass/baritone. The tenors get all the big arias, and all the girls.

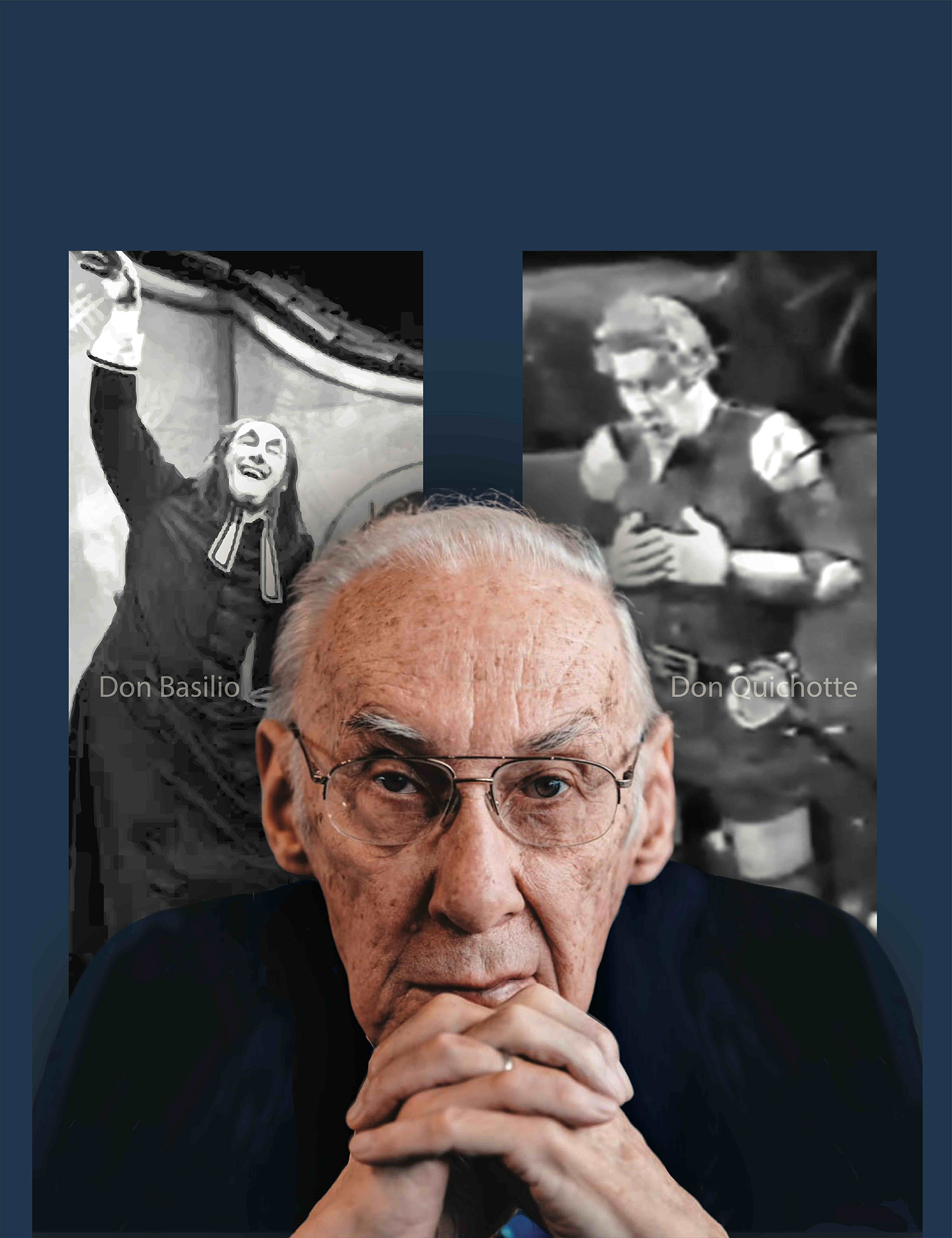

Voketaitis retired nearly three decades ago, but at age 92, he’s still a performer, and he still needs an audience. Which is why he often spends Saturday afternoons at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, 6500 S. Pulaski Road, showing films of his old performances to audiences that number somewhere between a dozen and a score of his fellow Lithuanians. The most recent showing was The Barber of Seville, from 1987 in Caracas, Venezuela, in which Voketaitis sang “Don Basilio.”

“Oh, I appreciate the thunderous applause,” Voketaitis cracked, as he stepped behind a lectern to a few polite claps. “It wrecks my ears. Thank you all for tolerating — attending — today.”

Voketaitis grew up in Connecticut, the son of parents who fled the Tsar, and still speaks with an old-fashioned East Coast accent that makes everything he says sound like shtick. In 1968, Voketaitis visited Chicago to sing in a Lithuanian opera. At the rehearsal dinner, he found himself seated next to a model: “Nijole. I wish you would mention that name. N-I-J-O-L-E. My head spun. I couldn’t believe it. I asked if she would be my guest at the Lithuanian production that followed the ball. It took her three days to say yes. Now, it’s been 54 years.”

The couple settled in Gage Park, which was, at the time, in the heart of Chicago’s Lithuanian community. That’s why the Balzekas Museum, which was funded by a second-generation Lithuanian auto dealer, is located in West Lawn. The neighborhood is almost entirely Latino now, but it’s still “Lithuanian in spirit,” says Sigita Balzekas, the interim executive director.

Although Voketaitis was never a big name opera singer, he is revered in the Lithuanian community, because he didn’t shorten his name to something easier for Americans to pronounce. In 1989, he was the museum’s Man of the Year. (An honor also bestowed on Senator Dick Durbin, whose mother was a Lithuanian immigrant.)

“He’s hugely important to all the emigre Lithuanians,” Balzekas says. “Arnold, at a very young age, chose not to change his surname, which caused him some challenges. He used it as a way to showcase his Lithuanian heritage.”

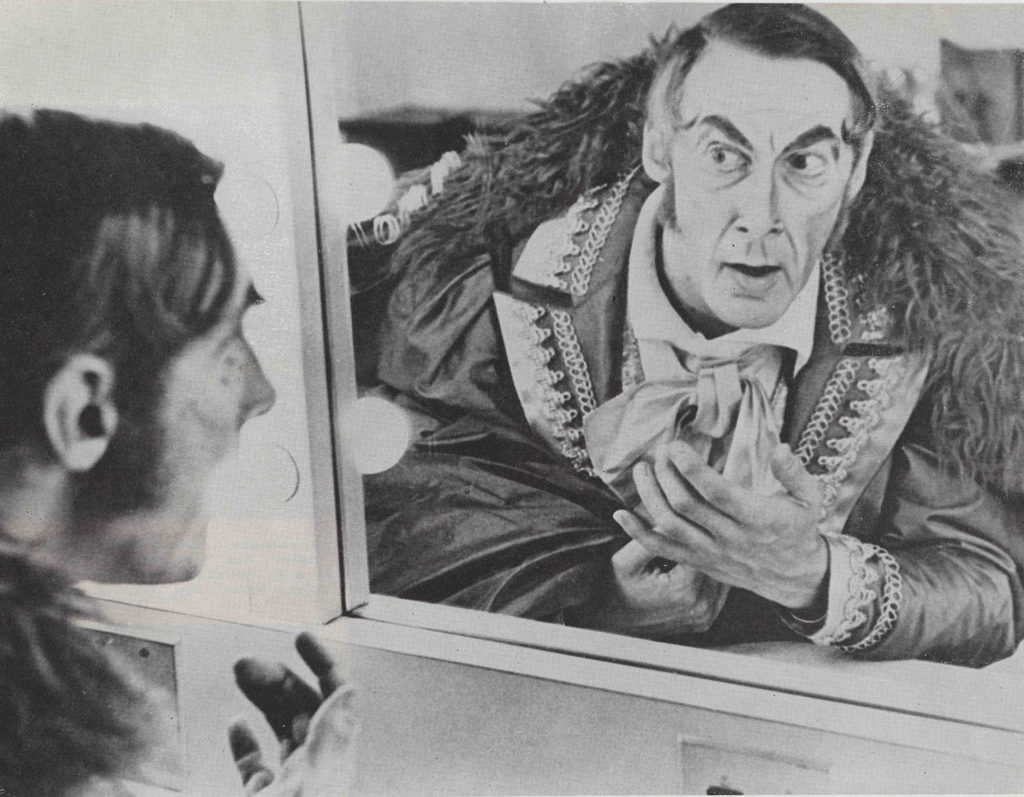

On to the show. Even non-opera fans will recognize the score from the Looney Toons cartoon “Rabbit of Seville” — especially the “Figaro, Figaro, Figaro” aria. Voketaitis appeared on screen about half an hour into the opera, wearing a Cyrano-length false nose. The Lithuanians broke into applause at the sight of a fellow Lithuanian onscreen.

“How did you like it up to now?” Voketaitis asked during the intermission. “Wasn’t I handsome up to now?”

The mostly elderly Lithuanians gathered around a table to enjoy plates of sausage and kugelis — a Lithuanian potato pudding — and kibitzed in their native tongue. Told that a reporter wanted to interview him, Voketaitis dug the tip of his cane into the carpet and propelled himself toward a table where his interrogator was sitting.

“I thought that part of my life was over,” he said eagerly — “interviewing.”

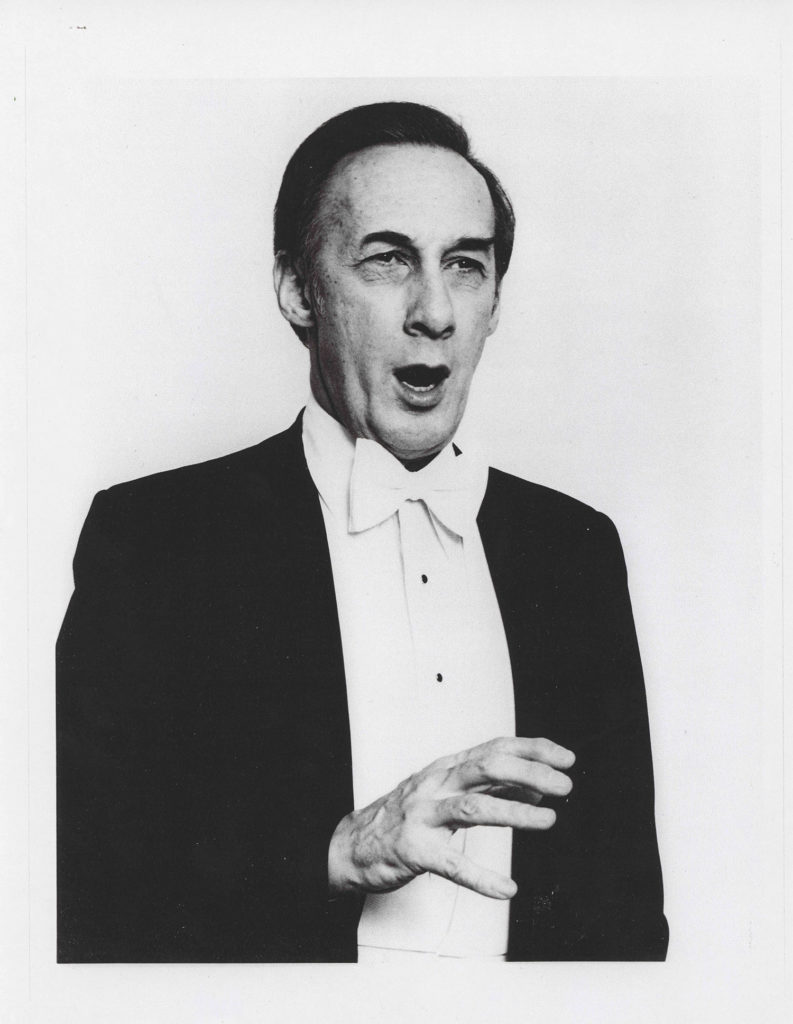

Voketaitis sat down and told the story of how he got his start on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts, the American Idol of the 1940s and ’50s. He was in the army during the Korean War, and won a singing contest.

“So then the United States Army Band put in a requisition for me to come to Washington for the commanding general,” he says. “Okay, I do it. So during that period, I represented the army on the Arthur Godfrey show. Remember it? You’re too young. The producer said, when you get out of the Army, come on the talent scout show. I come on the national talent scout show, and I win it. So an agent sets up an audition with the New York City Opera.”

Thus began a 50-year career that took him to stages in Mexico, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Washington, Minneapolis, and Dayton. Leopold Stokowski wrote him a letter praising his performance as Creon in the New York City Opera Company’s Oedipus Rex. Leonard Bernstein cast him in an opera. Voketaitis never forgot he was Lithuanian, and used his success to promote the music of his ancestors.

“My agent told me, ‘That ethnic name is unimportant. It’s the talent that perseveres.’ So I said, ‘You know, Arthur, I’m considering shortening my name from Arnold Voketaitis to Sam Voketaitis.’ He laughed. All through my career, when I was doing recitals, I’d sing a group of Lithuanian songs. And if I never did it, I’d always have one or two as an encore.”

The Barber of Seville, a digital rendering of a videotape, sometimes proceeded in fits. After the curtain call, Voketaitis returned to the lectern, and told a story about playing Faust in Mephistopheles, using his hands to demonstrate how slowly a hydraulic lift raised him to the stage. Then he sang a few bars of opera in his still-deep voice, wafting a hand to the music. He invited everyone to return to the museum on February 11, at 1 p.m., when he would show his starring role in Don Quichotte, from 1980 in Mexico City. He looked the part then, when he was leaner, and not at all stooped.

“Having a five-decade career, it’s highs and lows,” he concluded, “but those highs — you cannot write applause and audience acceptance of your work into a contract, because you put in so much hard work. At 92, what you do is, you live with your memories, and it gives you strength for the next day.”