When Houston Harrington Jr. was a child, he often wondered about his name. Who was Houston Harrington Sr.?

“Your grandfather,” he was told. And that was the end of the conversation.

“It wasn’t really discussed. And I never questioned it,” the 42-year-old says. Harrington Jr.’s grandfather died of cancer before he was born.

It wasn’t until much later, as an adult, that Harrington learned that Reverend H.H. Harrington Sr. was a renaissance man: Not only was he a reverend and inventor, but the elder Harrington was a songwriter, record label operator, and singer.

“That was really eye-opening,” he says.

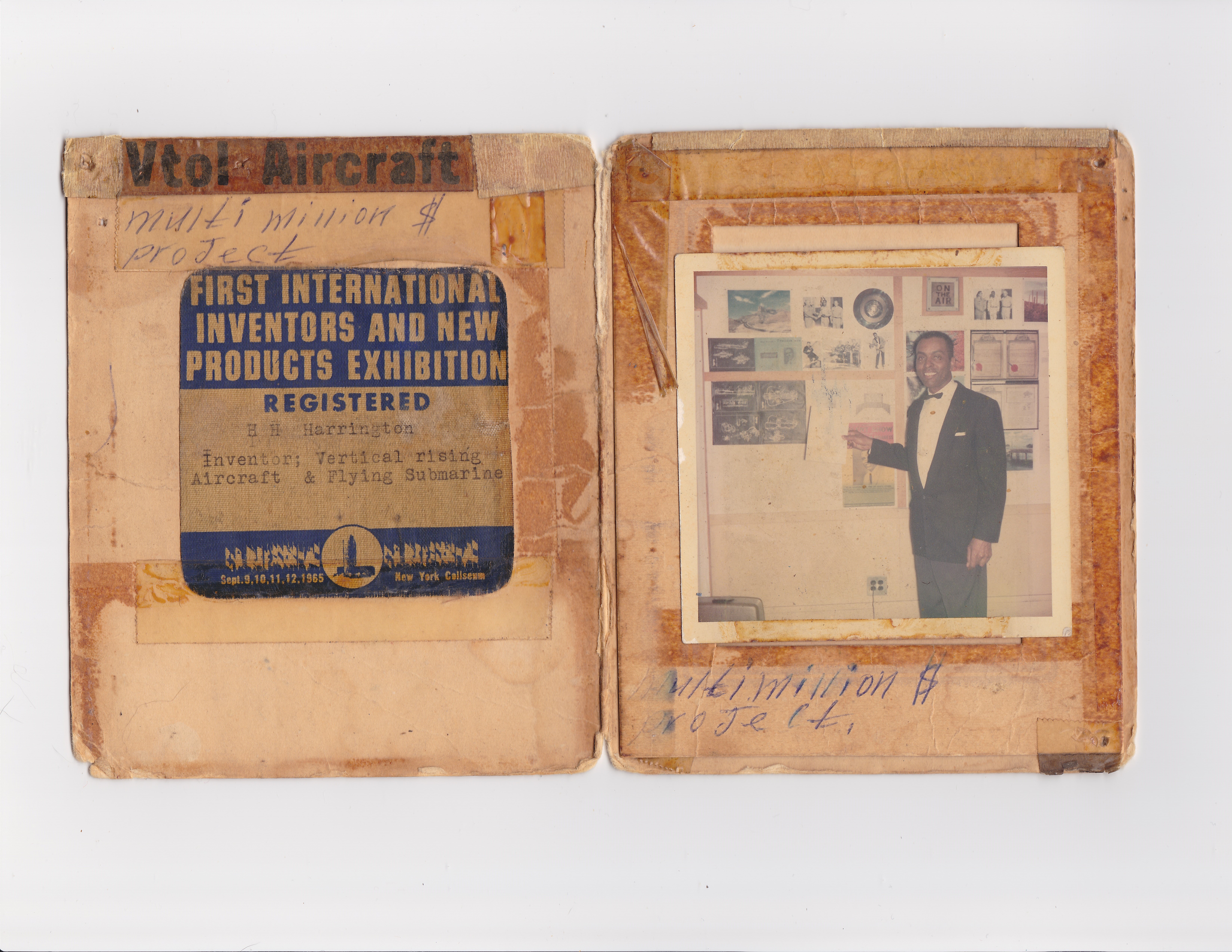

Now the world can hear the elder Harrington’s music, thanks to No Other Love: Midwest Gospel (1965–1978), a newly released disc of rare Chicago gospel recordings, released on the Tompkins Square label and curated by record collector Ramona Stout. Many were released on neighborhood labels that only pressed a few hundred copies. The CD jacket features a portrait of Reverend H.H. Harrington Sr. beaming in front of a wall of his patents. The two songs by Harrington — “Black Pride” and “Christmas in Heaven” — are lifted from only one of three 45 records by Harrington that his grandson owns.

“I doubt if there are any 45s of it left anywhere,” Harrington Jr. says.

Images: Courtesy of Ramona Stout

The history of Chicago gospel tends to be overshadowed by the city’s significant contributions to blues and jazz. But unlike those genres, gospel didn’t necessarily have one golden era. Instead, its evolution extended over decades, developing in neighborhood churches, auditoriums, storefronts, revival tents, and community centers. Thomas Dorsey organized the first gospel choir in 1931 in Chicago, but crossover artists didn't start recording on labels like Specialty and Vee-Jay until the 1950s and 1960s. By then, Chicago had already established itself as a commercial hub for gospel recording, with sheet music publishing and radio broadcasting companies promoting the music in its earliest days. By the time Mahalia Jackson started recording hits in the late 1940s, gospel was traveling around the world.

But unlike Chicago's most famous gospel stars — such as Jackson and James Cleveland — the artists on No Other Love had day jobs and mostly sang on the weekends. They also recorded for small independent labels that cut singles for play on local radio or to sell at their performances. Because manufactured runs were so limited, few circulated outside the Chicago area.

One of these was Atomic-H Records, the small label Harrington ran on the West Side. Atomic-H recorded gospel and blues musicians, including blues guitarist Eddy Clearwater, Harrington’s nephew. Other tiny labels represented on the compilation — Davis, Cash, and Righteous — were similarly diverse, documenting the sounds of their sides of the city during a fertile musical period.

“Had these men and women not taken the financial risk to make records, posterity would have lost aural examples of their singing,” says Bob Marovich, a gospel music historian and author of A City Called Heaven: Chicago and the Birth of Gospel Music. And had Stout, No Other Love's curator, not invested the time to find these records in attics and basements throughout the South and West Sides, “they would be lost to the larger listening public.”

Originally from the U.K., Stout grew up in Greece and London but became interested in vintage gospel when she arrived moved to Hyde Park in 2002 to study ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago. There, she met her future husband Kevin Speck, an employee at the now-defunct 2nd Hand Tunes and Hyde Park Records, and the two starting posting flyers and putting advertisements in small newspapers alerting people that they were paying cash for records. The offer served as an invitation to walk into the lives of strangers and get to know Chicagoans on a much more intimate level.

“I wanted to get involved in the whole city,” she says. “Music is a great channel through which to do that.”

By the time Stout and Speck moved to Crete in 2011, they had amassed about 20,000 records. They sold everything, but kept 10 boxes of records with them as they made their transcontinental journey. As Stout shuffled through the remaining stacks, she realized she could curate a compilation that told a unified story about the music. The performers are varied — some are church congregations, others family bands and children’s choirs — but the recordings had two general throughlines: All showcased impressive musical commitment, despite being nonprofessional groups, and unflagging proclamations of faith.

“The hope [in the performances] was for something unseen — not for material gain, not for a nicer house, but something beyond that,” Stout says.

In the process of assembling No Other Love, Stout, now 37, returned to Chicago last year to get to know family members of performers and ask for permission to include their recording in the compilation. In some cases, families had no idea their relatives made the record. According to Stout, all artists and their family members will receive royalties from the sales of the CD.

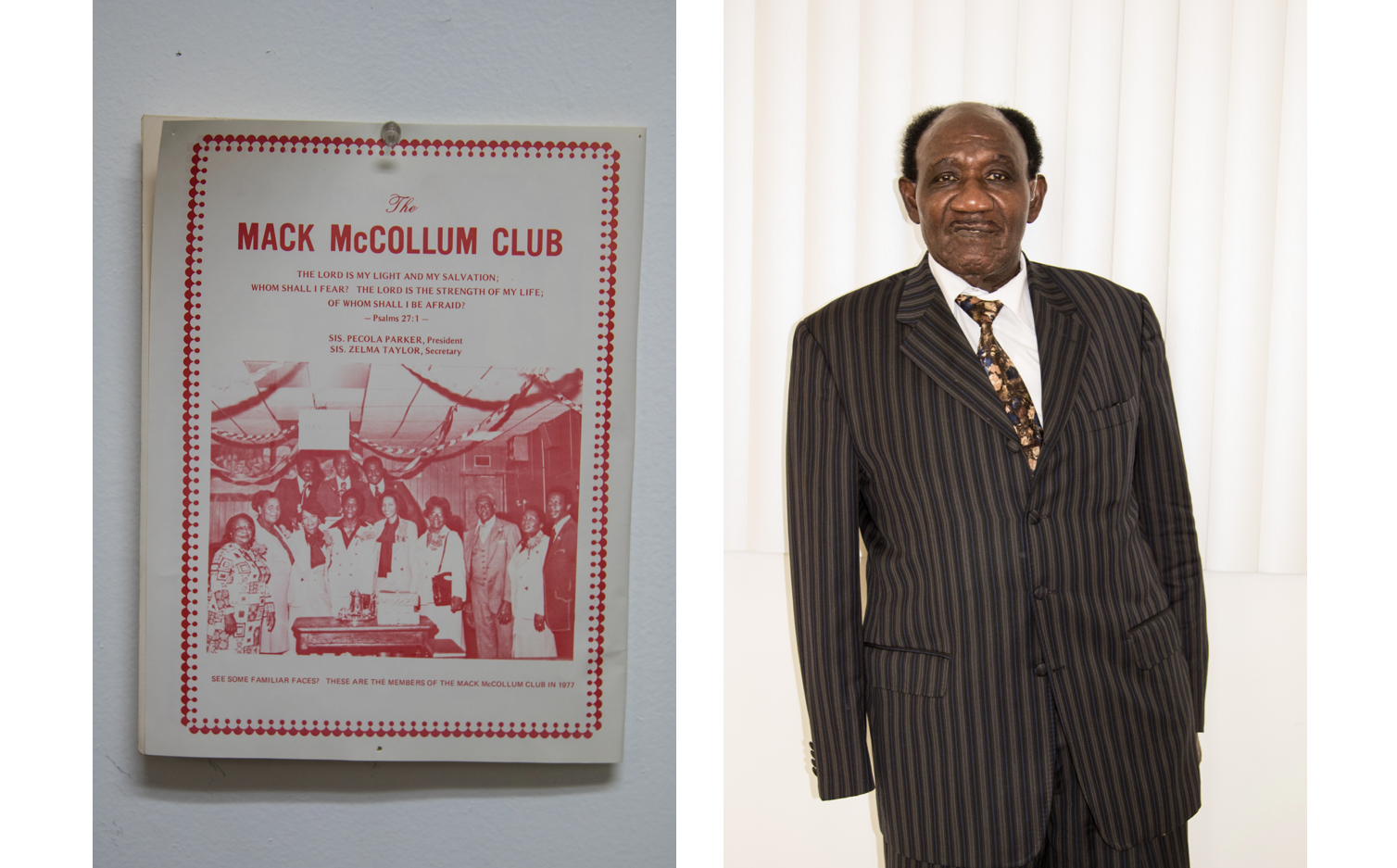

Through her visits, she met Rev. Mack McCollum, an 84-year-old preacher with the New Home Baptist Church, who continues to perform and record. Upon meeting Stout, he invited her to his house and performed a cappella for her. Another batch she bought were from a former worker for the IRS, who meticulously cataloged his 78 rpm records into giant ledgers; the records themselves were in likewise pristine condition. Some discs had sides that were completely worn out, while the other side was barely played.

“The physical aspect of vinyl is quite wonderful because it can tell you about the people listening to them,” she says.

As for Harrington Jr., he says listening to “Black Pride” — a record he never heard until Stout played it for him — gave him insight into the person his grandfather was. The song, recorded in the elder Harrington’s home on West 16th Street and featuring a band of all family members, is a sermon about living straight on the street. I’m black and I’m proud and I know I can say it loud, Harrington says over a throbbing bass line and flashes of electric guitar.

“He’s basically saying, 'Don’t be ashamed, even though they’re trying to make you feel ashamed about being black,'” Harrington Jr. says. “I listen to it all the time.”