“When I went to the Warehouse the first time, I was in awe of all that freedom,” says recording artist and producer Vince Lawrence. He’s talking about the long-gone but iconic West Loop nightclub with an inclusive, predominantly queer Black clientele and legendary DJs like the late Frankie Knuckles. Indeed, the term “house” comes from the venue itself.

Lawrence is a major character in a new documentary, Move Ya Body: The Birth of House, directed by Elegance Bratton and produced by Hillary Clinton’s Hidden Light company. On the film-festival circuit since its world premiere in January at Sundance, the film comes home for one screening on Wednesday at Lincoln Square’s Davis Theatre, as the opening-night presentation of Chicago’s Doc10 film festival. (It sold out over the weekend, but tickets remain for the afterparty at SmartBar.)

As the film makes clear, the history of the genre is intrinsically tied to the city’s history, in ways good and bad. Today there’s civic pride in being the birthplace of such an influential genre of music. However, key pieces of the house music story deal with oppression, not freedom. One of those elements is the infamous Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park on July 12, 1979, led by WLUP “The Loop” shock jock Steve Dahl. The racism and anti-gay bigotry that undergirded the riot gets examined in Move Ya Body — as does the sad old story of white executives ripping off Black musicians. Lawrence helped found Trax Records back in the day, but much more recently, he filed a federal lawsuit over the legacy and royalties of that company (as documented in our 2023 feature, “House Divided”).

Lawrence, who grew up all over the South Side, was a high-school student living in Lake Meadows and working at Comiskey Park during the summer of 1979, which gave him a ringside seat to the madness. But more impactfully and at an even younger age, he was connected to some Black music greats: His songwriter father was best friends with Eddie Thomas, who co-founded Curtom Records with Curtis Mayfield. Thomas also managed Chicago funkateer Captain Sky, who brought a 14-year-old Lawrence on tour with him during his summer break. “That was really inspiring for me. I came back from that summer break and I knew what I wanted to do with my whole life,” says Lawrence, who now runs his own music company, Slang Musicgroup.

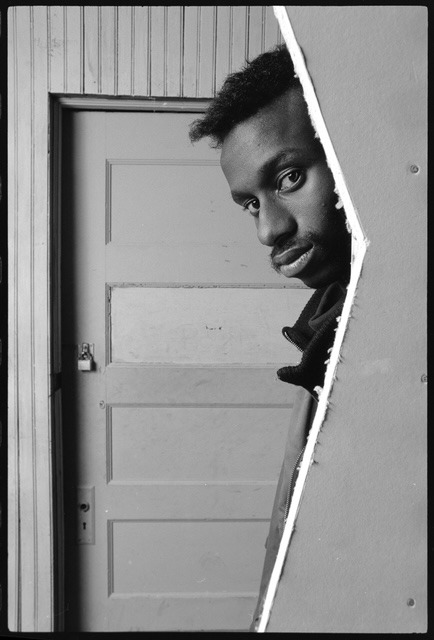

Also one of Move Ya Body’s executive producers and its primary narrator, Lawrence sat down with Chicago to talk about the new film.

When you were a teenager, how did you relate to disco? Did you identify it as Black music?

I grew up in the center of a big portion of Chicago’s Black music history, so I looked at disco records like I looked at any other record: by their parts, what format they fit into. I was a fan of a lot of music. I had three double albums that are big for me: Songs in the Key of Life by Steve Wonder; Electric Light Orchestra’s Out of the Blue — that’s the one with “Mr. Blue Sky” and “Sweet Talkin’ Woman”; and then Parliament-Funkadelic, Motor Booty Affair, the one with “Aqua Boogie” on it. You know, “Another One Bites the Dust” was a big record on my mom’s turntable in Lake Meadows. It’s amazing! It was cross-format — a rock record with a groove playing on Black radio. I digress, but that should give you an idea. I listened to a lot of music around that time.

You were working at Comiskey Park during the Disco Demolition — a Black kid who loved all kinds of music and listened to The Loop and probably didn’t fully understand what had suddenly erupted. Walk me through what you remember about that.

Me and my friends, we thought it was cool that we could get a double shift. I figured, if I have to walk to and from Comiskey Park, I might as well take the shift that gets me twice the paycheck. What was unusual that day was how many people turned out. At first, all of this “disco sucks” energy, chanting all over the building, was kind of fun — until it got to the part where I felt like people were yelling “Disco sucks!” at me. The only identifier for me being “disco” to these people was my skin color. It’s hard to take the Black out of disco. You know, it’s like trying to take the nougat out of your Snickers bar: You can’t separate the two.

So they’re agitated, and it was a little bit scary. Our supervisors told us we had to leave the building, and to be careful going home. Trying to leave Comiskey Park, these guys ran up to me, yelling, “Disco sucks! Disco sucks!” I was like, “Yo, I’ve got this Loop T-shirt on. What are you talking about?” They snapped a record in half right in my face, saying, “That’s what we do to disco.” That was frightening, but I also thought it was kind of a joke.

I have seen photographs of book-burnings in Nazi Germany, and they look the same as the Disco Demolition. I may not have understood it then, but that’s an act of violence against an entire culture. That’s terrorism: “Hey Black boy, watch how many radio stations you get on, because we’ll do something to you if you go too far.”

How did the Move Ya Body movie originate?

I had made a documentary during COVID: Legacy: From Horns to House, as an homage to my mentors. It aired one time, on WTTW, and we won some Telly Awards. This lady, Siobhan Sinnerton, calls me from London; she says, “I work with this company, Hidden Light, and we make socially impactful documentaries. Our founders are Hillary Clinton, her daughter Chelsea, and a man by the name of Sam Branson, who’s the son of Richard Branson.” Over time, more conversations and some writing happen, and eventually I went to the Toronto Film Festival and met everybody.

I talked to Hillary about the fact that she’s from Park Ridge, and how that under-your-breath but somehow still obvious racism still existed in the ’70s. And she told me this story about chocolate-covered broccoli: It’s a bunch of stuff you need to learn, coated in some stuff that you want to learn. That’s what this film is. Parts of it are a little heavy. That’s the broccoli. But we got all that dance music! House music is the chocolate.

Since Move Ya Body premiered at Sundance, it’s been playing all over the United States as well as the world — Greece and Canada, with upcoming screenings in Poland, Germany, Australia. That must be wild, hopefully in the best way.

It’s like a bunch of hot dance parties, and the film’s the DJ. Different aspects resonate with different people. The messaging and everything that’s happening with the film’s acceptance and success is an opportunity for me to be Captain Sky. If it can encourage one kid out there to go for it — you can change everything, you know? Anybody can get together with their group of friends and change the world.

What’s next for the film? And is it suddenly raising your profile anew?

There’s conversations about theatrical release. I know there’s been interest from multiple streaming platforms. I’m not the guy driving the bus, but I’ve got a great seat. Right as we were getting accepted to Sundance, I noticed an uptick in requests for Vince Lawrence to appear as a DJ. I like to say I DJ for sport, not an occupation. I can be choosy about the places and times. I love my wife and son, and if you’re DJ’ing two-three nights a week, you’re in record stores two-three days a week. But playing once a month, that works better for me now. At this point, time is the real commodity.