The first thing you must understand is this: The Harlem Globetrotters weren’t from Harlem, and they didn’t start out as globetrotters.

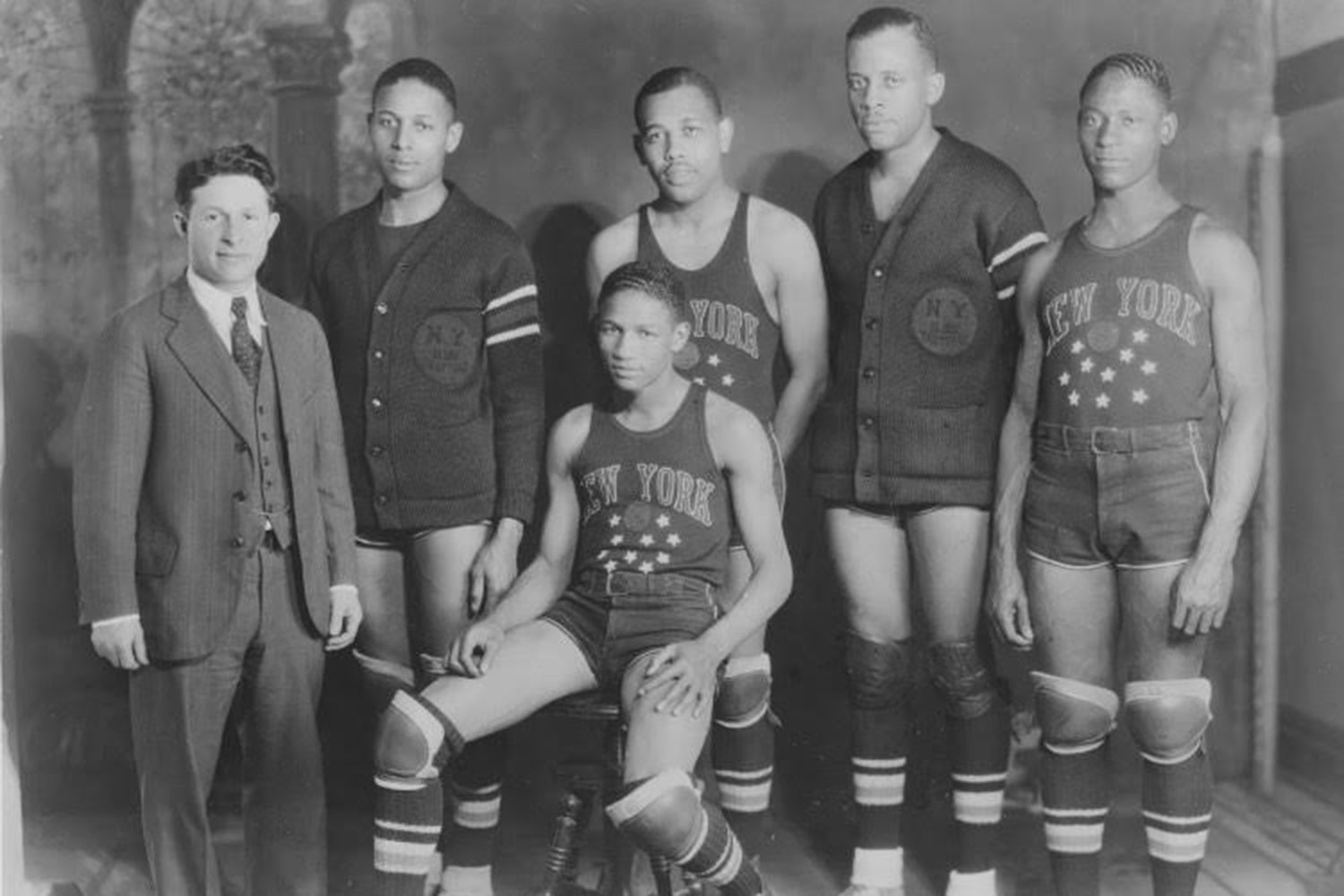

They were five Black basketball players from Chicago’s South Side, managed by a 5-foot-3 North Side Jewish guy named Abe Saperstein. They set off from the big city in a model-T Ford purchased from a funeral parlor in the late 1920s, with the goal of earning a few bucks playing local white teams in small Midwestern towns. They eventually parlayed their skill and comedy into worldwide fame, and they’re still going strong nearly a century later.

If you didn’t know the Globetrotters were from Chicago, don’t feel too bad. Lots of people don’t know that. Even the Chicago Tribune didn’t know it in 1940, mistakenly calling the Trotters “a Negro team from Seattle, Washington.” In a sense, they were from everywhere and nowhere, since they made their living on the road, with no home court.

I delved into the team’s origins while writing a new book with my brother, Matthew Jacob. Globetrotter: How Abe Saperstein Shook Up the World of Sports (published by Rowman & Littlefield on October 1) is the first biography of one of America’s most groundbreaking sports entrepreneurs, and we discovered many amazing things in our research.

We learned how Saperstein pioneered the three-point shot in basketball as a gimmick of his short-lived basketball circuit, the American Basketball League, in the early 1960s. We found how he helped keep Negro Leagues baseball alive by arranging barnstorming tours and promoting the leagues’ immensely popular all-star game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. We discovered how he got pitching great Satchel Paige and future Chicago White Sox star Minnie Miñoso into baseball’s major leagues.

We also found how he worked closely and sometimes secretly with the U.S. State Department during the Cold War to promote Americanism abroad, with his joy-spreading Globetrotters serving as a counterargument to the communist bloc’s depiction of the United States as a country that persecuted its Black citizens.

And it all started in Chicago.

If you visit Welles Park in the Lincoln Square neighborhood today, you’ll see pictures on the wall of the dedication of the gymnasium there to Saperstein in 1992, three decades after his death.

Welles Park was the birthplace of Saperstein’s sports career. He played baseball and basketball there, and when he found his own athletic ambitions limited by his small stature, he served as a coach. In that job, he met leading sports figures in other parts of the city, including well-known Black athletes from Bronzeville on the South Side. Among them: football luminaries Fritz Pollard and Dick Hudson.

The young and gregarious Saperstein managed to make friends with the South Side’s Black sports royalty less than a decade after the 1919 Chicago Race Riot. Saperstein wasn’t the kind of person to be governed by the past or by racial barriers. Hanging around Pollard’s coal company office, Saperstein and his more accomplished Black friends talked sports. And, boy, could Abe talk. The Black athletes soon figured out he would be the perfect person to schedule barnstorming games in downstate Illinois and neighboring states against white teams before white audiences.

Dick Hudson, assisted by Saperstein, formed a team called the Savoy Big Five to play at the new Savoy Ballroom on the 4700 block of South Park Way (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive). The Big Five was composed mostly of graduates of Wendell Phillips High School, but also included a Lane Technical High School grad named Inman Jackson, who would become Saperstein’s best friend.

According to Saperstein, the birth of the Harlem Globetrotters was a simple story: The Savoy Big Five broke up, and he formed the Harlem Globetrotters with some of the Big Five’s roster. But an alternative story told by one of the Big Five players, Tommy Brookins, is less tidy and more credible.

Brookins was a popular figure in Bronzeville, a talented singer as well as a basketball star. Decades after the events — and after Saperstein’s death — Brookins told an interviewer that the Savoy Big Five’s breakup led him to form a team called Tommy Brookins’ Globe Trotters, and he hired Saperstein as his booking agent.

Brookins vividly recalled a night when a fan visited his team in the locker room after a game in Wisconsin. “I also saw you guys the other night in Eau Claire,” the fan said. “You fellows are great.”

But the team hadn’t played in Eau Claire. Brookins said player Randolph Ramsey came up to him later and explained that Saperstein had set up a second Globe Trotters team composed of “all the players we didn’t want” and had sent that version on tour, too. Brookins asked Ramsey why he hadn’t told him that earlier, and Ramsey said: “I was waiting until you were in a good mood.”

Brookins said he confronted Saperstein, who responded that the second team was busy on tour and there was nothing to be done about it. This practice of putting multiple teams on tour with the same name would later become a regular practice for Saperstein’s Globetrotters. During the 1950s, they sometimes had three teams on the road at the same time.

If you assumed Brookins would hold a deep grudge about this, you would be wrong. “Actually, the news didn’t come as much as a shock as it might have,” Brookins recalled. “I had considered leaving my team anyhow because I received an offer to sing at the Regal Theater in Chicago for $75 per week. That was pretty good money then, even for a basketball player.”

Plus, Brookins’ mother was ill and he wanted to stay close to home. So Saperstein took over. Brookins said his only request was that Saperstein give members of his disbanding team a chance to make Saperstein’s squad, and Saperstein did so.

The two stayed friendly. Brookins had a nice career as part of a dance, song, and comedy duo with Sammy Van that toured widely, including in Europe. When the Globetrotters considered making their first European tour in 1950, Brookins wrote to Saperstein offering encouragement.

Saperstein called his team the Harlem Globetrotters to signal to white people that he was bringing Black athletes to their town. He wanted no surprises and no unpleasantries. The Globetrotters nickname reflected the braggadocio of Saperstein, who routinely inflated his team’s accomplishments in the early years. When the team was just getting started, Saperstein persuaded sportswriters to print absurd claims that his Globetrotters were “world champion” and had “played to practically every state in the union.”

The site of the first road game for Saperstein’s Harlem Globetrotters was believed to be Hinckley, west of Chicago. But the date of that game is in dispute. Saperstein claimed the first game was Jan. 7, 1927 — a starting date that the team still cites today — but that is highly suspect. If the team came from the Savoy Big Five and the Big Five began at the Savoy Ballroom on the South Side, it’s impossible, since the ballroom didn’t open until November 1927. An internal Globetrotters document that we found in a University of Texas archive admitted that the alleged start date was “very debatable.” January 21, 1929, is the most likely date of the team’s first road game.

While Saperstein’s origin story may be disputed, his results cannot be. He was the ultimate “fake it till you make it” promoter, eventually turning his team into a huge success that deserves a generous share of the credit for basketball’s worldwide popularity. Yet Saperstein’s role as a sports visionary is underappreciated. Caitlin Clark and Steph Curry owe him a debt as the first person to introduce the three-point shot in basketball league play. Saperstein was ahead of his time in other ways, too: pushing for basketball’s expansion to the West Coast, prodding baseball to speed up its games, and pushing the idea of variable ticket pricing based on the popularity of the opponent — something sports teams adopted more than half a century after Saperstein’s suggestion.

Some of Saperstein’s descendants live in the Chicago area and have tried to keep his memory alive. They shared countless family stories with us. As our book attempts to give Saperstein his due, many Chicago landmarks of Saperstein’s time have disappeared. That includes Chicago Stadium, site of his greatest triumph. In 1948, the Globetrotters defeated the all-white Minneapolis Lakers there in a last-second victory that built momentum for the National Basketball Association’s integration two years later.

Also gone are the Savoy Ballroom and the Saperstein family home at 3848 Hermitage Avenue. A historical marker in front of the Sapersteins’ old lot is weather-beaten and barely legible.

But Lake View High School, where Saperstein played bantamweight basketball, still stands. So does Wendell Phillips, wellspring of the early Globetrotters. And as already noted, Welles Park remains. The love of sports that Saperstein exuded is very much alive there.

One Saperstein landmark remains a mystery. We know he and DePaul basketball coach Ray Meyer came up with the three-point distance by taking shots at a Chicago gym. But we don’t know which gym that was. History is always partial and elusive. But if anyone reading this knows what gym it was, please let us know, so we can keep building on Saperstein’s amazing story.