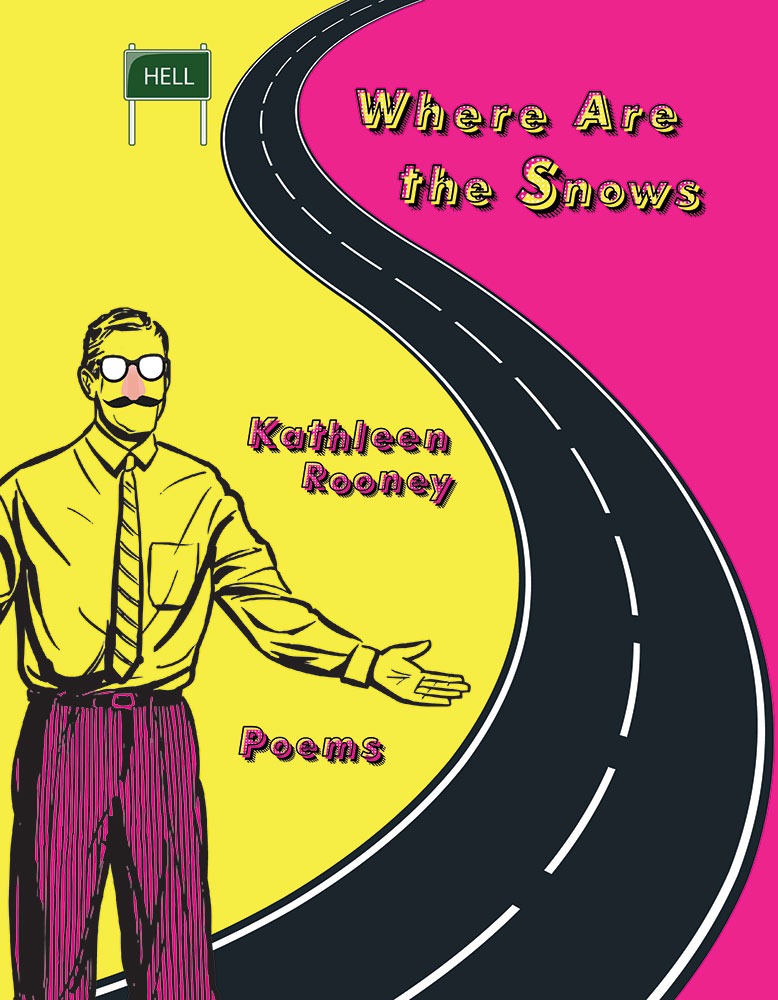

Kathleen Rooney — a Chicago writer and teacher at DePaul University — can frequently be found around the city typing poems on request as part of the Poems While You Wait team. A Ruth Lilly Fellow, she is also a frequent contributor to Chicago magazine. Her latest poetry collection, Where Are The Snows, was selected by Kazim Ali as the winner of the X.J. Kennedy Prize and will be published September 7 by Texas Review Press.

Composed during the pandemic, Where Are The Snows reflects the anxiety and pessimism of the era it was written in. But these aren’t brooding poems; they joke and play with a frenetic and irresistible energy. Rooney’s writing invites the reader to gaze through her window alongside her and get to know the birds, along with the thoughts that haunt and electrify her poetry. Rooney has written an immersive book of poems that observe motherhood, love, capitalism, and more.

You wrote the majority of the poems in Where Are the Snows during a single month. How did the constraints of that challenge influence the poems in this book?

Constraints are often where I find my greatest freedom. I give a ton of prompts when I teach creative writing at DePaul, and my fellow typewriter poets and I receive a ton of prompts when we’re out writing for strangers at Poems While You Wait. So I jumped at the chance to do the National Poetry Month poem-a-day group that my friend Kimberly Southwick put together for April 2020. There’s something attractive in discipline and dedication — committing to something that at first seems arbitrary, but through repetition and ceremony takes on deeper meaning.

In “A Court Game Played with Long-Handled Rackets,” you write, “I used to think: If I’m not trying hard, am I even really trying? Now I allow for the marshmallow fluff of goofing around.” That stanza strikes me as a type of ethos for this book. Why did you approach this project with that type of playfulness and what do you think playfulness adds to the collection?

Because of the community-based nature of writing poems that all of us in the group knew that everybody else would see, I felt hyper-aware of wanting to make sure that they’d have a good time reading any given day’s poem. Poetry can be a lot of things, but one of the things it can be is outwardly directed introspection. All of the poems are about subjects that I was (and still am) thinking about intensely, but it was fun to think of each line as part of a volley — whacking a thought across the invisible net and hoping the person on the other side would find it interesting enough to whack it around in their own head.

Where Are the Snows takes its title from François Villon’s 15th century poem “Ballad of the Ladies of Times Past.” What about that poem was calling you to engage it in conversation via Where Are the Snows?

History gives a long view of the human condition. Though the particulars differed, the broad strokes of being alive in the past were probably a lot like being alive now. People enjoyed the delights of their individual lives: games, dumb jokes, tasty food, their loved ones. But they felt dismayed at the bigger sorrows they were up against collectively: war, plague, death, greed, political ineptitude. The Villon poem is an “ubi sunt,” Latin for “where are they,” used to meditate on transience. Villon’s poem haunts me because its content is basically “where are all the people in the past who thought they were so huge and important? Dead, just like we’re going to be.”

In “A Human Female Who Has Given Birth to a Baby,” you say “This is a poem that will make a lot of people hate me.” I’m interested in two things: One is the use of the aside as a poetic move — as a type of spoken caesura before turning back to the matter at hand. What was your editorial process like for Where Are the Snows? How did you decide which asides to keep and which to cut?

I love that you home in on that line. I added it based on feedback from the group. Because the poem gets irreverent toward sentimental attitudes about motherhood, it got people agitated even within that small community. That line is a way to add a measure of self-awareness, letting readers know that strong opinions are coming up and they might not like them, but I still hope they’ll stick around. My editorial process consisted of a lot of cutting and adding that kind of audience-directed material to create that sensation of a volley — poetry book as racket sport.

And why do you believe that “A Human Female Who Has Given Birth to a Baby” will make a lot of people hate you?

Any time I mention that being a mom in our grind-until-you-die American culture is a raw deal and that the sacrifices capitalism demands of mothers are ones I don’t want to make, people get mad. I’m interested in other ways that society could be arranged. Like I say in the poem, “I don’t want to ‘mother,’ per se; I just want to care for others like any person should care.”

I was struck by the frank pessimism in some of the poems in Where Are the Snows. As a reader, it felt refreshing. What is your relationship to hope as a writer?

Toxic positivity frowns on any acknowledgement that a lot of things systemically suck. But as far as hope goes, I have a lot of it. Despair is what oppressors everywhere hope the oppressed will sink into because then they’ll give up. Pessimism is a starting point, not an end one. In order to bring about the better world that we all deserve and that is totally possible, we might first have to admit: “These conditions are awful.”

Though Where Are the Snows is expansive, it’s also quite local. We join you on walks and observing the world through your window. In particular, birds feel like intimate companions in the poems. What birds have been visiting your window lately, and what is your relationship to them?

It’s very capital-P poet of me, but I love birds. We have a pair of hummingbirds who live outside our third-floor apartment. Martin and I are in awe. They’re incredibly tiny and beautiful, yet also smart, tough, and determined. I don’t know if Zum Zum and Li’l Zum (they’re a mom and daughter) can ever know what they mean to us, but we hope that somehow, when we put out their food and make eye contact, they can tell we love them a lot.