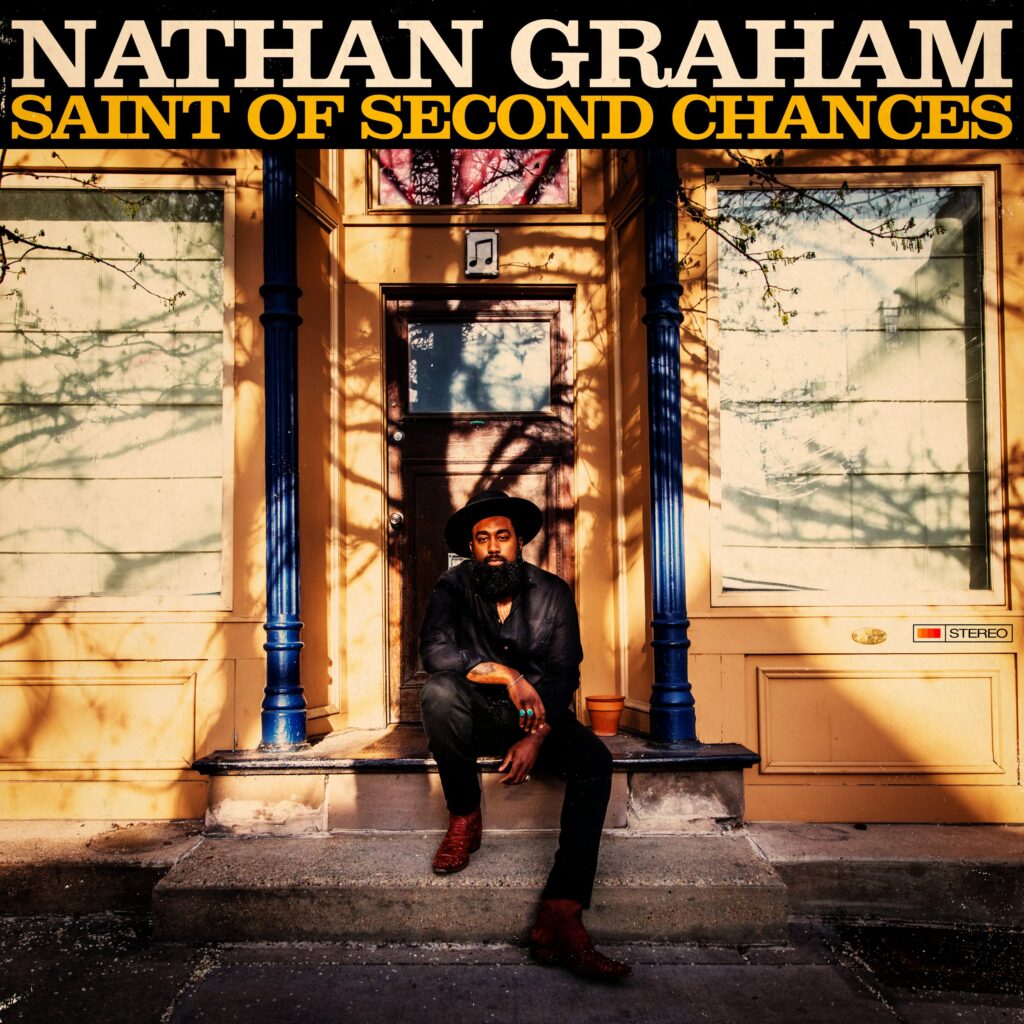

Chicago has a healthy contingent of singer-songwriters. Several bleed into the “alternative country” category. Chicago native Nathan Graham, whose debut solo album, Saint of Second Chances, was released last month on the Pravda label, gravitated early on toward the local alt-country scene; his music soon evolved into something more eclectic, but still with a rustic flavor. And being Black in a white-dominated field, Graham has a unique perspective.

“When you think about the term ‘singer-songwriter,’ a lot of people have somebody that jumps into their head. A lot of times, it’s not a Black person,” Graham says. “It bothers me.” An obvious example is Bill Withers, known for standards like “Lean On Me” and “Ain’t No Sunshine” that still endure today. “That’s the thing,” says Graham. “You wouldn’t even have him be categorized as ‘singer-songwriter,’ you would have him categorized as R&B.”

In fact, Graham argues that the genre cards have been misshuffled since the early days of rock. “I think Chuck Berry was really one of the first Black country guys,” he says. “The storytelling of ‘Maybelline’ is a country song, because it’s not like [sings] ‘diamond in the back, sunroof top…’ It’s not talking favorably of your car, it’s talking about why won’t you just run the way I want it to run!”

This kind of candor is what attracted Graham, 33, to country and Americana. “I fell in love with poetry, and I fell in love with telling a story that wasn’t necessarily shrouded in metaphor. But it was very straight to the point; very direct, like you were having a conversation. That’s what country and Americana kinda meant for me. It wasn’t metaphor, it wasn’t buried under 13 layers of irony.”

Graham’s connection to this kind of music goes back to his childhood. “My parents were both really into music,” he says. “My dad was more into singer-songwriters, sort of like John Denver, Bob Dylan, a lot of those type of people. My mom was pretty much into everything. If it had a beat, she would listen to it.”

By his own admission, he was open enough to listen to “anything” himself, but he had a special affinity for the genre that’s often referred to as Americana. “I didn’t really see a lot of people that looked like me doing anything in the rock ’n’ roll or Americana or country space, right? It wasn’t a lot of that, so I really had to seek out people that did that sort of thing. I would listen to Ben Harper, or I would listen to Lenny Kravitz. Lotta Charley Pride in there… That’s what I wanted to listen to. That’s what I wanted to hear. It was like, man, there’s only four or five of us.”

Graham began as more of an instrumentalist, with vocals creeping into the picture later. “I started out as a guitar guy. I couldn’t really sing before. I don’t really think I’m a good singer now,” he modestly laughs, “but I wanted to play guitar, and I loved blues music, and I loved rock music. I just started getting into Chicago blues clubs. The older Chicago blues acts, they were very supportive. I had to have been about 15 or 16 when I actually started playing in clubs and bands.”

Getting his feet wet in the blues scene, he was hanging around venues like B.LU.E.S., Kingston Mines, Rosa’s, and a soul food restaurant on Chicago’s South Side called Captain’s Hard Times Dining. “I used to play with this guy named Vance Kelly, I used to play with Carl Weathersby, Fernando Jones, and then as I kinda got into college, my professor was Nicholas Tremulis,” who urged Graham to start writing more songs.

Graham cycled through several iterations of blues and blues-rock bands before he started taking Tremulis’s advice to write. “I was kind of getting back to my roots in a sense, with my mom listening to ‘The Sound of Philadelphia’ and Motown and anything coming out of Stax Records, and my dad listening to singer-songwriter stuff,” Graham says. By this time, he says, “I found a market for it, because all of a sudden Nathaniel Rateliff was a thing. Leon Bridges was a thing. There’s a space for that! It’s not weird what I want to do!”

When Graham found his groove as a songwriter, he realized that the songs Robbie Robertson wrote for The Band was a major influence. “I wanted to ride the line between country and the blues, a little bit of rock and soul,” he says. When you’re crossing lines between genres, though, there’s always someone wanting to confine you musically — or even visually.

“I showed up to a recording session in Nashville,” says Graham. “The guy was like, ‘Oh, the hip-hop session’s tomorrow.’ I was clearly holding a lap steel! Sometimes, when I play those country licks…especially being from Chicago, they go, like, ‘How did you learn this? How did you figure this out? What’s the story here?’ The alt-country scene has been really big in Chicago for a very long time; Nashville really just got into the alt-country scene maybe in the last 15 or 20 years.”

While Graham fully owns his country leanings, he’s conscious of not being confined: “I’m not straight-up any kind of music.” Indeed, Saint of Second Chances includes elements of Southern soul and indie rock along with the acoustic country textures. “When you think about the prospect of the Black singer, there is a want and a need for you to be very quote-unquote soulful,” he says. “You have to have this big voice and you have to do a bunch of runs, you gotta do the church thing.”

While Graham does have a soulish tint to his voice, he’s every bit as home singing rock or country as he is R&B. “I love playing music anywhere and everywhere. That being said, sometimes you get tired of hearing yourself play. I do want to make more strategic moves to not burn myself out,” he says. “It makes you more excited about the project, instead of making it something you have to do.”

Graham plays an album release show for Saint of Second Chances at Sleeping Village on November 18.