A visit to Candice Lin’s solo exhibition A Hard White Body, a Porous Slip at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center Gallery can only be described as deeply disorienting. In a dimly lit room, a curious brew of brown liquid is distilled in a glass contraption — it is, in fact, urine — producing a smell faintly evocative of a public shower. A thin pipe leads from this scientific contraption to a larger room, where newly purified water periodically drains into a large pool in which white porcelain fragments and ephemera float. Lin prompts us to kneel, crouch, inspect, and, ultimately, work hard to make out elements in the pool that refer to her research on racialized and gendered histories, from James Baldwin’s queerness to French botanist Jeanne Baret’s masculinity. It is only appropriate that the environment is unsettling, as it invites visitors to consider how prejudice is comparable to repugnance.

A video projection also plays on a suspended sheet of plastic, appearing like a work in progress. Titled The Beloved, it features an omnipotent voice describing porcelain as having the uncanny “hardness of a superior white body." Lin also appears, scanning her own face to create a three-dimensional rendering; the gesture draws a direct connection between the poreless, impervious Oriental surface so desired in the 18th century and avatars in today’s increasingly digitized world.

A Hard White Body, a Porous Slip is Lin’s third and final installation in a series of three other exhibitions that debuted in France, at the Bétonsalon art center, before traveling to Portikus in Germany. The exhibition shares some visual elements such as allusions so the bedroom in Baldwin's Giovanni's Bedroom, while also looking like a vastly different ensemble in each iteration. I spoke with Lin about her inspirations behind setting the scene in Chicago, her thoughts on political art, and making people uncomfortable.

What made you choose to work with porcelain? I'm fascinated by all the research you did on the material, and how you found that European traders described porcelain as a “hard white body.”

What was interesting about porcelain to me was how it complicates the black-and-white conversation around race that happens in the United States. For example, porcelain was spoken of in terms of its whiteness and purity — which is anti-black — but it was interesting to me that that racialized logic was built on an Orientalist desire. The porcelain bedroom that I sculpted and left unfired in the exhibition at Bétonsalon slowly yellowed over time, grew moss and mold, and cracked.

In many ways, your work does not rely on human presence to necessarily critique racist or sexist perceptions. What draws you to focus more on the objects that ornament people’s lives (Baldwin’s room, Jeanne Baret’s ship cabin) rather than the bodies that inhabit them?

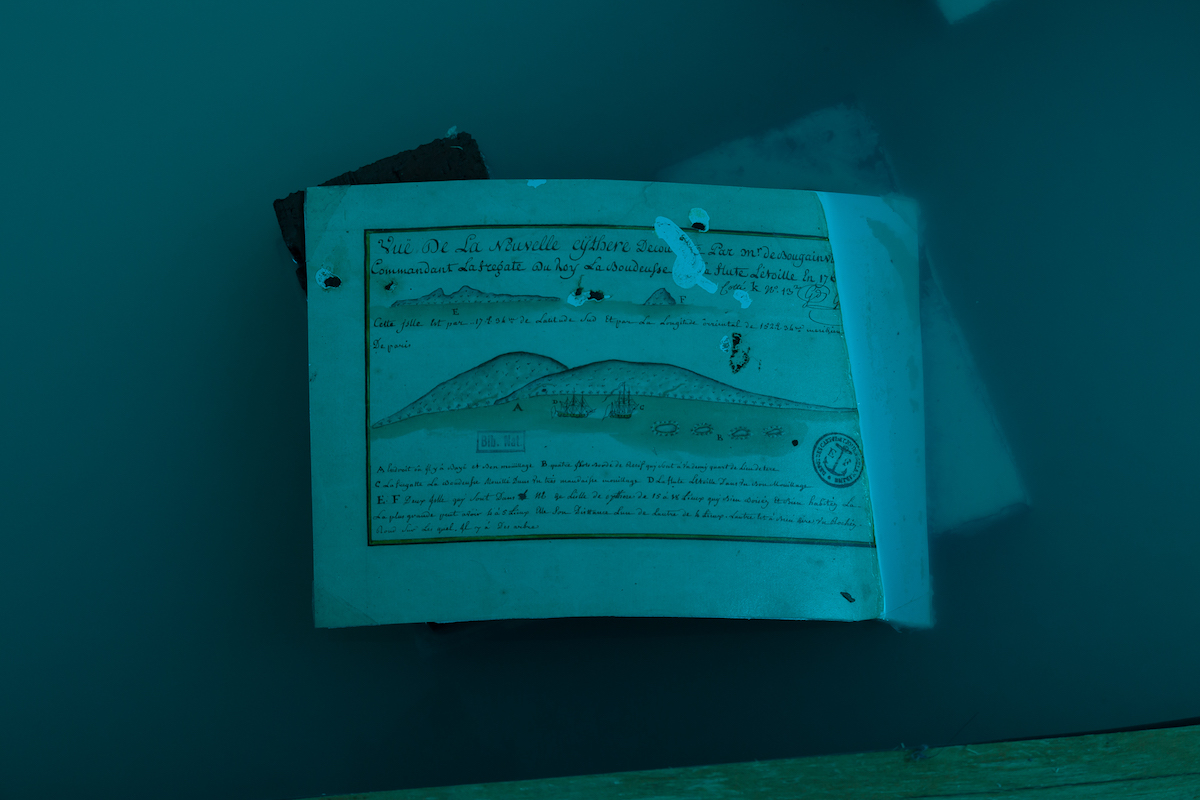

Well, I think the work is doing both. It’s animating specific histories that aren’t very well known in relationship to the objects. My research for A Hard White Body was drawing from Lisa Lowe’s Intimacies of the Four Continents and Mel Y Chen’s Animacies. I was trying to think about how nonhuman others are instrumentalized in our language and cultural value systems. And I wanted to look at how the gendered and sexual language with regards to colonial bioprospecting of plants and the racialized language of porcelain revealed European anxieties of that historical time period.

Lowe uses the example of chintz, a fabric that appears in William Thackeray’s novel Vanity Fair and conveys a sense of racial anxiety by serving as the backdrop for racial drama. Her book was a strong model for me to think about how the materials that I’m using are inlaid with entangled histories but also specific dramas. Lowe is building upon Elaine Freedgood’s argument for the “fugitive” histories that can be read into the “things” in Victorian novels; Lowe’s proposition is “to read objects and contexts with attention to what they say about lost histories, and the layers of occlusion which have resulted in a forgetting of the ‘intimacies of four continents.’"

In A Hard White Body: a Porous Slip, the bedroom I portray could be from Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room or Jean Baret’s ship cabin, but it’s also made of materials that have these other lost histories that form alongside human histories and are perhaps more occluded and missing from archives.

Why did you choose to set the scene so viewers have to crouch down to read the text and observe materials that appear to be very unpolished and industrial?

The invitation for viewers to kneel or crouch in order to access the research material was in all three versions of the exhibition. This was deliberately to try to get viewers to have an awareness of their bodies and a non-alienated relationship between their body and the artwork.

The piss also functions in this way, where it changes the intimacy of the work environment around the exhibition by requiring all the people who work on the show to contribute their piss. There’s usually a lot of giggling involved — there’s discomfort and humor that comes out of the idea of mingling and smelling pee. This shifts our bodies and our ways of looking and physicalizes the involvement of all of the people who take care of the exhibition — which is, in a sense, alive and dependent on their care to function.

The plywood, bricks, and plastic sheeting were supposed to evoke the feeling of being under construction. That’s something very present in Giovanni’s Room, where Baldwin talks about the room that Giovanni and David lived in was always under renovation. Giovanni was always trying to fix it for the promise of a better life. So, I was thinking about this idea of being under construction and relating it to the fact that archives will always have histories missing as they are not being recorded or are constantly being constructed. It’s a critique that’s actually quite hopeful because it makes the idea of history or “the archive” less monolithic and more open and fluid.

Since you mention being able to smell the urine, can you talk more about how you activate other senses?

Well, I think the intention of activating other senses is to focus on the parts of the body that are not about visual mastery. So when you come in to the exhibition, you are first confronted with a smell. You might not even be able to identify it as urine. You might discern it as vinegary. It destabilizes the usual art-viewing experience and makes it much more sensory and somatic.

The distilled urine is slowly pumped into the main pool of liquid porcelain slip that holds all the porcelain fragments of the bedroom and the research materials that went into making the exhibition. As the amount of urine increases over the duration of the exhibition, the water level rises and slowly destroys the drawings and research materials. In terms of this liquid deterioration of the research material, from the rotting papers to the silkworm remains, this was also a way to speak to how things require constant care, and are changed by all of our bodies in the room – human and non-human – which affect how and what things are invisible and what disappears from an archival process.

How do you view yourself within the current landscape of political art that claims to “resist” and “empower," especially as it pertains to race and gender? Do you necessarily see your work as doing any of these things?

That’s an interesting question. I will start by saying that I don’t think my work empowers or resists, necessarily. My work is interested in what resistance there exists already in material histories. Porcelain, for example, is still prized for being hard and white. Ceramicists still talk about it in those terms without thinking about the colonial past that is still embedded in its value as a material. I’m trying to make us rethink individualism, so maybe “entangle” would be a better description. Or maybe “decentering” the human, white, male, liberal subject.

Candice Lin: A Hard White Body, a Porous Slip runs through October 28.