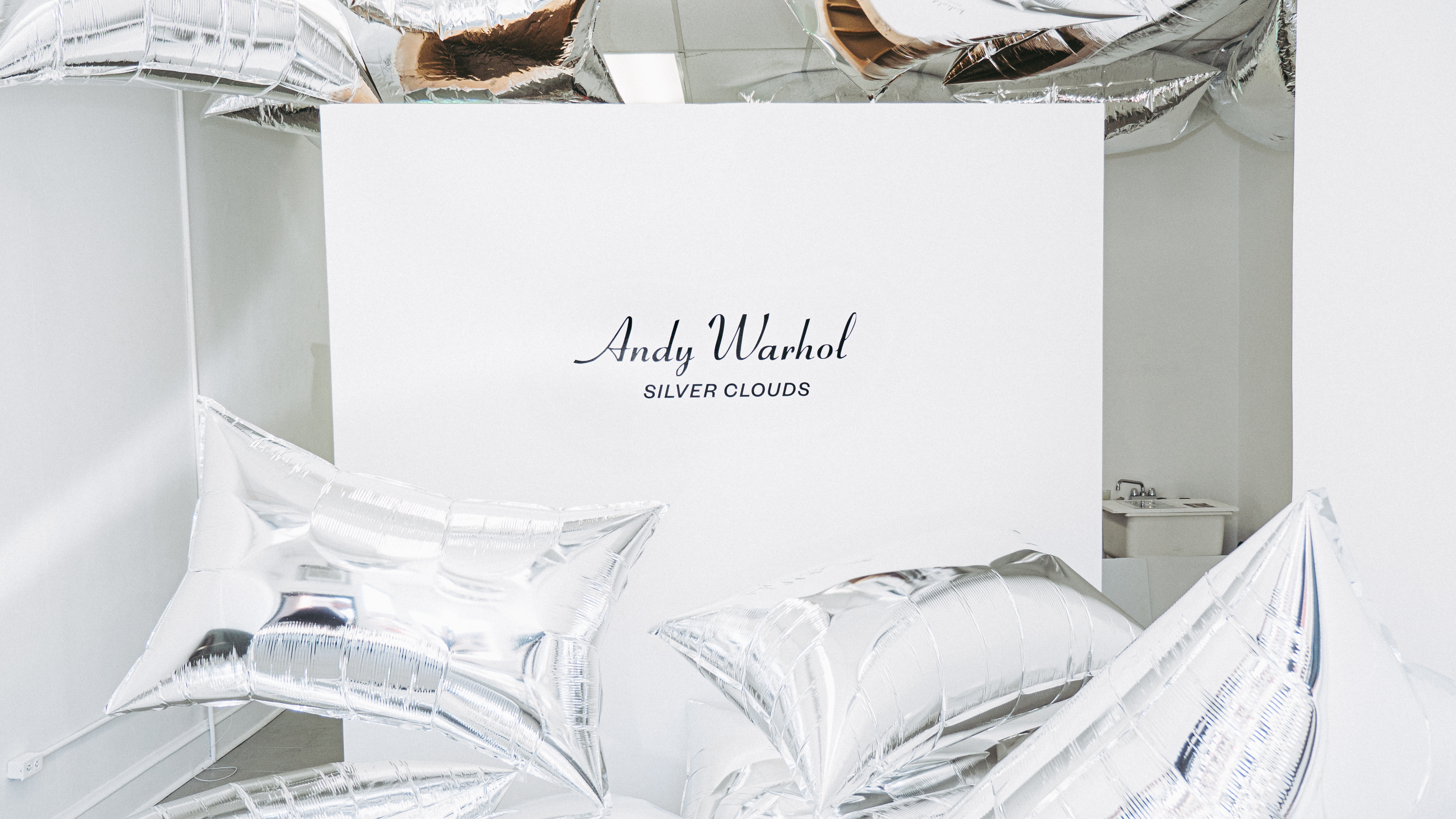

It’s hard to miss the curious objects currently bobbing around the storefront of Lawrence & Clark gallery in Ravenswood. On a sunny day, their metallic surfaces glint like jewels, catching your eye from across the street. Get close, though, and you’ll see that they are free-floating, pillow-shaped balloons.

This cluster is the brainchild of none other than Andy Warhol, who first exhibited the immersive artwork, titled Silver Clouds, in 1966 at New York City’s Leo Castelli Gallery. Today, Lawrence & Clark opens this iteration of Silver Clouds to the public, marking the first time the clouds have been shown in Chicago as a standalone installation in nearly a decade.

Anywhere between 20 and 40 balloons float in the compact space — “depending on the wind currents,” says gallery owner Jason Pickleman — and visitors can engage with them however they wish. On Thursdays, the gallery will play music inspired by the Velvet Underground; improvisatory dancing is encouraged.

“I've sat on the floor and danced with them, batted them around,” Pickleman says. “I've sat here as though I'm on the bank of a river, watching them float by [like] leaves falling off a tree.”

Warhol developed the balloons with Billy Klüver, an engineer at Bell Telephone Laboratories who frequently collaborated with artists. Klüver had introduced the pop artist to Scotchpak, a material used to make Ziploc-esque pouches. Scotchpak was an innovative way for midcentury housewives to store food, but Warhol immediately realized that, with a little helium, he could turn it into something wondrous and whimsical.

The clouds have since popped up at countless cultural sites throughout the city, from the Museum of Contemporary Art — which hosted a revival of Merce Cunningham’s 1968 dance piece RainForest, meant to accompany the floating pieces, in 2017 — to the Art Institute of Chicago, where they floated in 1989.

The Art Institute of Chicago is itself the current site of a traveling Warhol retrospective, but it did not have space to host Silver Clouds this time. When Pickleman found out that the museum would not be exhibiting the work, he wondered if his gallery could take up the challenge.

“It was a pie in the sky idea,” he says.

A curator with the Art Institute introduced him to the director of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, which is responsible for producing all the balloons (these days, they're made of mylar), and Lawrence & Clark was eventually approved for a loan. The museum sent over 180 deflated clouds to cover the exhibition’s two-month run; Pickleman and his assistant revive them with a helium tank in the gallery’s back room.

Silver Clouds heralded a meaningful shift in Warhol’s creative practice. “He thought his career as a painter was over,” Pickleman says. “The clouds were Warhol’s attempt to bring the energy of his studio… into the world and make his environment public.”

According to Thea Liberty Nichols, an interim exhibition manager at the Art Institute of Chicago, Silver Clouds exemplifies Warhol’s “push against a medium’s boundaries, an impulse so central to his artistic production.” Visitors to the Art Institute’s retrospective can see other examples of this compulsion in works like Screen Tests, a series of black-and-white films that double as portraiture, and Warhol’s iconic Elvis paintings, in which the singer seems to flicker on the canvas.

“When Silver Clouds first debuted at Castelli Gallery in 1966, Warhol called them paintings that could ‘float away,’” Nichols says. “Referring to these kinetic sculptural objects as paintings is signature Warhol.”

Pickleman is hopeful that aligning his exhibition with the Art Institute’s will introduce a new audience to his art gallery, which is one of only a handful in the area.

“There aren't any museums around here, so to bring work of the highest order to this neighborhood is important to do,” he says.

When the exhibition closes on January 4, 2020, Lawrence & Clark will have to destroy the balloons, according to the provisions laid out by the Warhol museum. In the meantime, the gallery will be tending to its puffy flock and keeping watch on specimens that start to sag.

“Lately they've been feeling like my children or my pets,” Pickleman says. “They all behave so differently.”